|

|||||||||||||

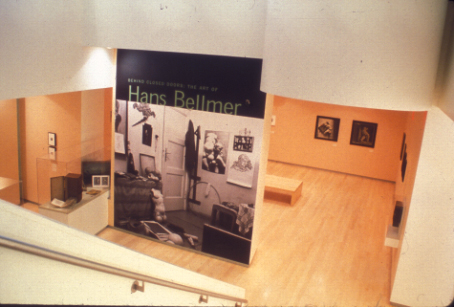

Behind Closed Doors: The Art of Hans Bellmer

In every section and room of this exhibition, Bellmer’s

photographs of both the first and second doll (completed in 1935)

were prominently installed, even in the gallery concerning early

“pre-doll” context. Lichtenstein and Putman wanted to

be certain that the viewer would always have Bellmer’s main

works in mind when considering the mediating influences. Bellmer

produced at least thirty photographs of the first doll, and one

hundred of the second doll, each time changing the pose, states

of dress or undress, hair, accoutrements, and settings, which included

domestic interiors and outdoor scenes. The paint color chosen for

this first section was a sensual, fleshy peach. Combined with the

dolls, the erotica, and the lighting softened by colored gels, it

created the feeling of being in a boudoir, both lovely and somewhat

forbidden (illustration 2). Throughout the exhibition, the lighting--

in combinations of pink, yellow, and orange-- picked up the colors

of the hand-tinting that Bellmer often used on the doll photographs.

The gentleness of the green and pink pastel tints seemed to mock

the violent positions into which he would twist the dolls, and Putman,

along with her lighting designer, Hervé Descottes, wanted

to achieve a similar ambiguity in the installation.

The second section, “Bellmer in Nazi Germany,”

the crux of Lichtenstein’s thesis, was the most minimal in

design of the three. In this room the content was allowed to speak

more directly for itself. The paint was left a stark white, although

the same lighting scheme was used, this time either illuminating

the works from below, or by installing lighting directly into the

walls of the main entrance of the gallery (illustration 3), which

maintained the sense of being in an alternate realm. Here, the viewer

initially confronted numerous images of the first papier-mâché

doll in poses varying from prostrate and vulnerable, to coy, with

over-the-shoulder glances. Two vitrines, shorter and less dominating

than the aforementioned erotica-filled cases, contained the kind

of Nazi propaganda to which Bellmer would have been constantly subjected

after Hitler took power in 1933. This propaganda included a 1935

edition of the journal Das Deutsche Lichtbild (German Photography),

with photographs of healthy, tanned, Aryan youths, catalogues from

the Great German Art Exhibitions of 1936, 1937, and 1938, Nazi-sponsored

shows of sanctioned artwork, often highlighting Hitler’s favorite

sculptor of classical Greek rip-offs, Arno Brecker, and an original

brochure from the 1937 Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich in which

the Nazis tried to lay out a cohesive argument that any art relying

on primitivism, expressionism, or pure abstraction was corrosive

to a healthy society. This led Bellmer to declare that he would

no longer make commercial work that contributed in any way to the

economy of the fascist state and to retreat into the studio to create

a body of work that stood in stark contrast to the Nazi program.

His production was a self-proclaimed “remedy, the compensation

for a certain impossibility of living.”3

Examples of how Bellmer’s reaction to this

repressive environment leaked into his work were immediately accessible

to the viewer through the photographs of the second doll that were

placed on walls adjacent to the Nazi-era vitrines (illustration

4). The construction of this doll was more complex than the first

in that the center ball joint Bellmer had fashioned with his brother

Fritz could have numerous appendages attached to it. He often photographed

the doll with multiple legs, and in one piece he hand-tinted angry

red spots on the legs, making them look inflamed with disease, and

thus providing a foil to the sculpted bodies sprinting through the

Nazi magazine pages nearby. Directly behind the vitrines was a disturbing

image of the doll propped against a tree in the woods, with the

shadowy figure of a voyeur standing behind the tree. In a perfect

blend of social and private, the figure functions as a stand-in

for Bellmer and the fantasies he could act out on his dolls,4

but concomitantly for the watchful and repressive regime within

which he created work that would be damned as degenerate if discovered.5 An element which allowed Putman to dramatically

foreground her design in this section was the crown jewel of the

installation, the actual second doll (La Poupée, dated 1932-45

due to elements of the first doll being incorporated into the second)

which was lent by the Centre Georges Pompidou in France. The work

was located in an intimate room just beyond the gallery with the

Nazi printed material and placed on a platform made to look like

a bed, with two blankets thrown over it on which the doll and her

double pair of legs rested (illustration 5). Putman insisted that

the blankets be the kind used for packing and shipping artwork,

for two reasons: Bellmer used the same type of padded, stitched

blankets as a backdrop for one of his strangest doll photographs,

one with the ball joint and a leg, a bow and blond hair, but no

head, and a long string with a detached eye (see illustration 37

in Lichtenstein); also, the colors one often finds in these blankets

are, like the dolls themselves, a weird mix of sweet and ugly, like

“piss yellow and sucked-lollipop pink.”6 The

platform was shrouded behind a scrim, and the translucency of this

material combined with theatrical lighting installed along the bottom

of the floor indulged the spectators in voyeuristic pleasures, inviting

them to peek into a forbidden zone in order to get to the core element

of the exhibition. Putman used a similar setting (without the packing

blankets) to display La Poupée in the 1998 Guggenheim exhibition

Guggenheim/Pompidou: A Rendezvous.

After encountering the grandiosity of La Poupée,

the viewer then moved into the third and final section, “Bellmer

and Surrealism.” Aspects of this section reflected those of

the first: pastel hues, this time in light green, and tall vitrines,

although the second time around the disconcertingly “pretty”

color and huge vitrines were not as jarring to the eye. The cases

contained Surrealist books and journals that bore Bellmer’s

influence7 spilling out of the boxes and drawers. Breton

and Paul Eluard, the leading poets of the Surrealist movement, were

introduced to Bellmer’s work by his adored cousin Ursula when

she went to Paris to study at the Sorbonne. She brought eighteen

photographs of Bellmer’s first doll to Breton and Eluard, who

so admired them that they were published the same year in Minotaure.

The two poets understood that Bellmer’s project was an attempt

to explore the same subversive, sexual realm that they tried to

use in their work as an alternative to the dictates of bourgeois

existence. Since Freud’s sexually-based readings of the subconscious

became a powerful weapon for the Surrealists in this battle against

the bourgeoisie, the boxes, drawers, and valises that contained

the Surrealist journals carried as much metaphorical weight in this

section as in the earlier section with the erotica. Bellmer finally

left Germany in 1938 after his wife’s death, and came to Paris

to join up with these kindred spirits. In the 1940s he began collaborating

with the renegade Surrealist, Georges Bataille, on his book Story

of the Eye. Original dry-point engravings of the illustrations for

the book were installed in wall vitrines toward the end of the exhibition.

Bellmer lived in France for the rest of his life, and the section

on Surrealism thus appropriately functioned as the conclusion to

the retrospective. |

|||||||||||||