Androgyny and the Mirror: Photographs of Florence Henri, 1927-1938

|

|||||||||||||

The boundaries between scholarship and personal information have been over the years something I am less and less interested in maintaining. I have realized that strict boundaries between the professional and personal benefit more those whose privilege allows them to concentrate on one thing at time, or whose areas of concentration do not compete and conflict. In other words, to maintain a single and exclusive vision, it helps, first off, to be minimally involved with children, and, secondly, male or heterosexual. These aid clarity, unity and high investment in one set of signs, or values. If, however, the signs of one's life, when assembled or made visual, are less clearly readable, are, perhaps, mutually contradictory, what forms does the image take? If the composite creature that one is leads to a hall of mirrors, of play, double-play, re-play, of positive and negative, competition between elements, of nothing one can say with absolute certainty, then how will the role of formal, impersonal scholarly discourse fullfill its intensive demands for the singular statement, the thesis? Likewise, the authority of the scholarly stance, depending upon a theoretical platform, suffers vertigo when there is no ground to stand on, with an artist, such as Florence Henri, whose vision is the double, duplicity, play, signs which cancel themselves, where everything made manifest is equally impossible. I had been struggling with my conclusions to the mirror photography of Florence Henri for some time. That Henri presented an androgynous vision by playing with opposites and ignoring all their boundaries was, I felt, well-established in my visual analysis. The conclusion, however, eluded me, the result of a subject that snaked past any subject category, any placement, any typical scholarly summa. Then, my four year old daughter put the conclusion in my lap. She pulled from my shelf Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own and began to "read" it. I was amused and so reread that day my twenty-year-old underscorings. I did not expect to find what I did. Written in the very same year Henri's mirror photography began, Woolf's thoughts on mirrors, androgyny, and craft echo the destabilizing and recoupling of Henri's contemporaneous vision. My topic was enriched purely by accident but in a way also befitting its subject—the construction of a serendipitous, possible space, an borderless no-place, where two women who could not possibly have known each other faced the daunting tasks of putting together the signs of their lives through arts that had, traditionally, refused them. Over sixty years later, as I write these words, I understand these pressures, being, too, a creature in an age where I am given the right to produce but little tradition for how to accomplish this with the complexity and inherent contradictions of my life as a woman, mother, writer, and scholar. In the spirit of these considerations, I will introduce biographical information from the life of Florence Henri, as it is relevant to her mirror photography. The visual effects of the photographs themselves carry the associations of androgyny, but knowing that the photographer was bisexual aids our understanding. Without attempting any claims for a "bisexual vision," I will show that bisexual concerns, more precisely, conceptualized androgyny, infused her work. The concept of being double and doubling, fundamental to this mirror photography, provides the metaphoric territory for such concerns, which, I wish to add, are not essentialist nor causal, but motile, fluid, intellectual, questioning. The concept of androgyny provided a space for visual ideas, not a statement, nor a definition. What Henri's mirror photography presents is a vision that consistently defeats definition, that opens up space and simultaneously blows apart placement. Her manipulation of signs of masculine and feminine point to a preoccupation with androgyny, yet the space is consistently indeterminate, mysterious, "factually" presented through photographic realism, and physically impossible. It is a vision from a woman engaged in conceptualizing androgyny, and committed to synthesizing what to others are contradictions. In her work of 1927–1938, Henri introduced a vast array of reflection and doubling techniques that share in the experimental spirit of New Vision photography but find in suggestiveness little counterpart in the work of others. Completely absorbed during these years with the effects of reflectivity, her work presents a panoply of doubling and double ideas that raise issues of self-absorption and self-exteriority, the questioning and instability of space, confusion and interplay of form and plane, as well as the suppression and elimination of characteristically photographic phenomena—those of time, record, documentary detail, social factors, gesture, instantaneousness, and spontaneity. We can in fact assert that the mirror is Henri's fundamental vision. Through it, she rendered the art codes of her time, which were fundamentally unadaptable to the medium of photography, photographically verifiable.1 In this manner, she weds photographic verisimilitude to visions which are, seemingly, antithetical to photography. Taking the overlap of planes and superimposition of points of view characteristic of cubism and foreign to the camera's monocular instant of seized time, Henri blended forms through aggressive mirror duplication into a photographic realism that questions the very realism upon which it simultaneously relies.

This tense union between seeming opposites indicates careful and deliberate choice on the part of the photographer, who, as Diana C. Du Pont asserts in her catalogue essay, thought of the photograph "as a constructed image" in which her "intellect...is always self-consciously present."2 The mirror and its metaphors suggest this self-consciousness, and no where more than in Henri's self-portraits. Yet, at the same time, they in their spatial and planar ambiguity effectively empty or make unstable realism and symbolic significance. They serve to make the subject herself unstable and her presence, as well as her relation to the viewer, layered, ruptured, enigmatic. All reflectivity in her work becomes a metaphoric extension of this topos—one that introduces the subject to make it ambiguous, that provides "personality," in the form of portraits, only to reveal it as a reflection, or as an abstract idea; one that calls in question identity and objective nature and carries this uncertainty further in the suggestion of a female sexuality free from objective and static positing. Henri's reflectivity empties traditional significations of object, objectivity, possession, and position, and substitutes for it a mobile field of carefully composed suggestive forms that concern more creative play, an act of juggling signs, than the reality upon which they, photographically, lay claim. To write about Henri is enter the space of the mirror, which destabilizes and inverts what it also clearly reveals. If such instability is a mark of both the mirror and the Henri photograph, it, too, was a factor of the photographer's youth.3 Henri spent her minority shuffled around Europe and twice orphaned. Leaving New York at age two, never to return, Henri was left with her maternal relatives, after the death of her mother. A frequent traveler, Henri's father took her to the major capitols of Europe until they settled with her younger brother in 1906 on the Isle of Wight, in England. After only two years, when Henri was fifteen, her father died, leaving her an income. She took up residence in Rome with her aunt, Anny Gori, and her husband, Gino, who ran the Cabaret del Diavolo in Rome, a hot-spot for musicians and artists such as John Heartfield, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, and the Futurist circle.

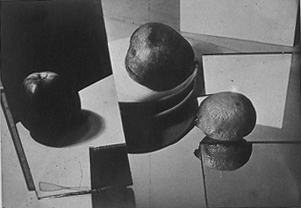

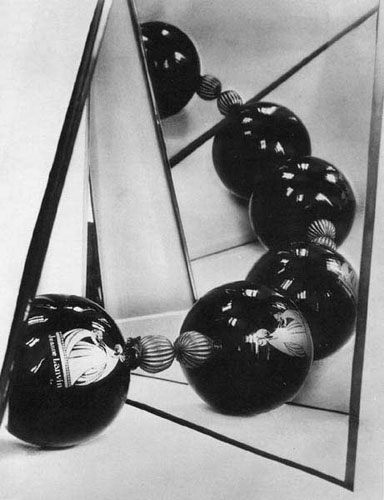

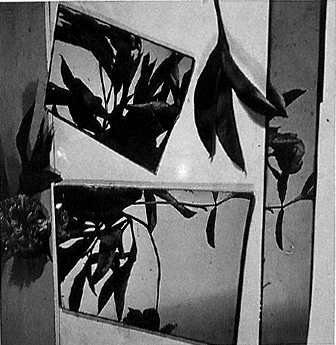

After early success as a concert pianist, Henri gave up music for art, while living in Berlin during the war, a fertile place for the avant-garde. At this time, she met the coming-to-prominence art historian, Carl Einstein, who fell in love with Henri and proposed marriage. She and Carl traveled to Italy together, but, when she tried to enter France in 1924, she was declared "stateless" and forbidden to enter. Rather than accept Carl's proposal, she chose, instead, a marriage of convenience to a Swiss domestic servant, who provided her with citizenship, entry to France, and the art world lauded by Einstein, as well as a last name, "Koster," which she seldom used but when she did she misspelled, with a "C" for the "K." From 1924 onward, Henri is a French resident with Swiss citizenship who calls herself American, traveling frequently to Germany and Italy, with artist friends scattered across Europe. Motility, instability, and independence—whether by choice or circumstance—are principle factors of her early life. Motility, independence and indeterminacy are also factors of her sexuality—an aspect of her life others have chosen not to discuss in print. The circumstances of her relation with Einstein remain a mystery. We do know, however, that she never married in earnest—only as a means to buy a passport—nor did she have children, though she maintained close and life-long friendships with many men and women. Further documentation is required in this area, but it is the conclusion of at least one scholar, who has supported this through interviews, that Henri was bisexual.4 With a photographic syntax that shifts between ample masculine and feminine associations and consistently empties them, the intellectual activity of Henri's vision becomes a field of play for desire that eludes labels, including "bisexual," yet may be denoted as "androgynous," or doubly-sexed.5 The Paris art milieu helped to form Henri, through studies for a short while with André Lhote's Académie Montparnasse, and then, more significantly, with Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant's Académie Moderne. During this time, she was painting in an international constructivist style, when a visit to a friend, Margarete Schall, at the Bauhaus completely changed her direction. Henri enrolled as an unmatriculated student for the summer of 1927, with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Vasily Kandinsky, and Paul Klee as her teachers. At this time, she was thirty-four, and her maturity made her the friends as much as the pupils of her teachers. A close friend was the photographer, Lucia Moholy, who personally encouraged Henri to pursue photography. Moholy's emphasis on structure and architecture must have struck a sympathetic chord with the painter's constructivist training. Also influential was Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Lucia's husband, the "formmeister" of the Bauhaus. His course, though not specifically a photography course, emphasized the radical camera-optics later to be called the "New Vision." In his text, "Photography is a Manipulation of Light," Moholy-Nagy emphasized not the objects the medium renders but the play of photography's light-sensitive values.6 He advocates "tricks," bird's eye and worm's eye views, oblique angles, the use of mirrors and transparent surfaces, cutting, pasting, and superimposition,7 and the collapsed and over-layered imagery of urban life reflected in shop windows with their "superimpositions and penetrations."8 In Painting, Photography, Film (1925), three of Moholy-Nagy's photographic examples show reflective objects or a room reflected in a glass ball or convex mirror.9 He further advocates the use of mirrors and other "contrivances" for a "revaluation [sic] in the field of photography."10 Henri, however, did not use mirrors so much for a reevaluation of the field, but, rather, as a means by which she can double–reality, gender, sexuality, and potential. Both a prosthesis and womb, inverted and inside-out, the camera in Henri's hands becomes androgynous. Moholy-Nagy disparaged "the associative,"11 which forms for Henri a material "text." Yet, from her teacher she gleaned an awareness of optical fidelity and visual complexity. The Henri photograph doubles visual fact along with associative material and redoubles these until there is no ground or act to stand upon except that of the process of doubling itself, thereby emptying customary signs into the sheer force of signification. Mirrors were part of the Léger aesthetic, as well. In his avant garde film, Ballet Mécanique, of 1923–24, Léger employs a mirrored prism device suggested to him by Ezra Pound via Alvin Langdon Coburn and his prismatic vortographs. This device causes a multi-partite splitting of the subject and a dizzying sway of motion in its reflections. Through both the use of mirrors and quick cutting, simple industrial and household forms seem to slide together, interpenetrate, and ricochet, suggesting the concerns of cubist painting. No doubt Henri knew of this film and probably saw it, either through Léger himself or through her myriad artist friends.12 Henri's cubistic style, therefore, grew not only in response to the Léger–Ozenfant school of painting but perhaps more significantly to the photographic practices of experimentalism and reflectivity of both Léger and Moholy-Nagy. In the stimulating and collegiate atmosphere of the Bauhaus, Henri found herself unable to paint, but she did a few photographic exercises. The earliest known Henri photograph is Window Composition (Communal Bath in the Bauhaus), 1927.13 I think it not insignificant that Henri took this first or early photograph from within the room of a communal bath. The darkened, steamy space where naked bodies of women commune with water and perhaps with each other suggests a primordial area, a watery birth, from which issues of sexuality, identity, vision, and exteriority can emerge as though reflected in the Bauhaus structure outside the brightly planar windows, a structure that links to Lucia Moholy's architectural photographs, the Bauhaus as an institution, and the building as pure, masculinized form, a form penetrated (in a feminine manner) by sunlight. The issues of Henri's next eleven years as a photographer are here encapsulated—reflectivity, identity, rebirth, sexuality, the body into form, and the slipperiness of light which can indicate the inconcrete nature of photographic realism. Henri's inability to paint continued when she returned to Paris through the autumn of 1927. She began early in 1928 a series of photographic experiments using mirrors and friends as models. Encouraged, devoted herself full-time to photography. A group of mirror and ball compositions along with a self-portrait received the attention of her teacher, Moholy-Nagy, who published them in an avant garde Dutch magazine 10, later in 1928.14 This began a quickly accelerating career of photographic exhibitions, publishing, and commercial work.15 Henri's spatial photographic techniques rapidly grew in sophistication and complexity throughout these eleven years. The ball and mirrors compositions of 1928 used only two mirrors and one ball. Nonetheless, the forms seem to float in an spaceless space, and Henri's careful sense of composition arranged the billiard balls so that the seam of the mirrors intersects the ball's reflection of a reflection in a way that makes illusion apparent. This seam flanks the actual ball, setting it apart as the "actual" object, and the linear forms of the background set off the primary reflection. A gate or grates separate the actual space from the reflected and double-reflected spaces. These spaces, though ambiguous, flattened, and seeming at first to float are visually reconstructible as a real setting. In a Still Life Composition #10 of 1928, Henri used the same techniques and billiard ball, but the space becomes unreadable. What is resting on or underneath the ball? Where is gravity? Only when one flips the print upside down does the space become readable, and we can understand her simple but ingenious trick.16 The inversion sets gravity right, and we can see that this is one ball, with a household sieve which sits, closest to the picture plane, on top of the ball, surrounding one round form with the frame of another. We can tell this by the shadows of the mesh on the highlight of the ball as well as by the reflection which is rendered in limited focus (making it more abstract). This limited focus is a factor of mirror vision which is not readily apparent to the eye sans camera. The mirror reflection, in a different plane of focus than the object it reflects, will, in the camera's vision, be out of focus, if one adjusts the focus to the object. We seldom notice this in perceptual life, however, since our eyes too quickly adjust to differing planes of focus for us to notice that they are different. Henri exploits this aspect of camera vision to assert its paradoxically non-realistic potentials. In the fruit and mirrors still lifes of 1929 (fig. 3), Henri used four mirrors, three pieces of fruit, a couple of white boards, and a bowl and saucer, in each, to fracture and parcel space. The direct, side lighting produces chiaroscuro effects as well as an ambiguity of shadow. Though complex, they are still re-constructible, and part of their challenge is for the viewer to decipher the placement of objects that Henri actually photographed. Employing principles from cubist painting, Henri made them photographically verifiable—a matter of planes and reflection rather than multiple exposure. There is no question that this, though creating a pieced effect, is one entire shot, and that is its frisson. The scene, though fragmented, begs for reconstruction. In another print,17 an apple exists only as reflection; the plane of it chops off the saucer from our view. The reflection of the lemon cuts across three mirror planes which neatly fragment it with dense black line, and the lemon itself hides what we know by reflection to exist—the seam between two mirrors. These seams and croppings suggest a violence to the organic fruit, a domination of planar vision upon natural objects. They exist not as independent objects, but as vision; or, rather, they may not exist at all, suggests the photograph. They are insubstantial. An undercurrent of sexuality—masculine form containing feminine objects—runs through these images, but the mirrors confuse this traditional function. Henri also employed montage—Still Life, 1929 (fig. 5),18 and Abstract Composition #76, 1929 . In the first, Henri appeared to have irregularly cut the borders of photographs which depict reflections of leaves. I suggest she placed these prints upon a table covered with white and rephotographed them with actual plants. The ambiguity of this image rests in the tip of a leaf which crosses the border of one of the prints and appears to be reflected there, as in a mirror. This telling detail becomes a point of fixation—is it a "real" reflection, or a match on the shape of real leaf and imaged leaf? She picked up the line of one imaged leaf stem with the line of another across a gap that separates the two prints. In addition, the tonal value of the table to the left matches the tone of the print backgrounds. It is no easy matter to distinguish between real, reflected, imaged, or actual here, and the play between two and three dimensions gives this photograph an especial lack of fixity. In the second image, Henri, instead of a bird's eye view upon a table top, produced a worm's eye view (both reminiscent of Moholy-Nagy). Here, we look up at a windmill, which Henri photographs twice similarly, taking the two subtle variations on the same view, a near double, inverting one (as a mirror inverts), and splicing them together on one board to form a montage which doesn't at first appear to be a montage but rather one windmill gone awry. Retouching of the seam to smooth over the splice and of the vanes on the windmill to more strongly contrast with the sky, as well as a stippling effect to give the sky a granular quality, reinforce the over-all design. The retouching also downplays the cutting of the montage, increasing the illusion of the singular shot in this mirror-effect image.19 In Still Life Composition #10, 1931, Henri, suggests Du Pont (45), has placed a mirror near the lens to reflect the shadow of the chair in a highly ambiguous manner. This compound image seems to exist in a strange "space-time warp," so that the abstractionist aesthetics of Henri's day prefigure our day's science-fiction of "hyper-space." In her series of Vitrines, or store front windows, c. 1930, we see other reflections forming the urban superimpositions that Moholy Nagy called for. Reflecting a world of three dimensions into the planes and patches of two, these recall the work of Eugene Atget, which were shown along with Henri's in the "Foto-Auge" exhibition of 1929.20 Henri's, though, make space virtually unreadable. In Mirror Reflection at the Flea Market, Henri has masked a central portion of the negative during printing, so that this strip appears in the print to be tonally lighter, increasing the sense of dislocation among the mirrors, lamps, and the one furtive and androgynous person caught doubly.

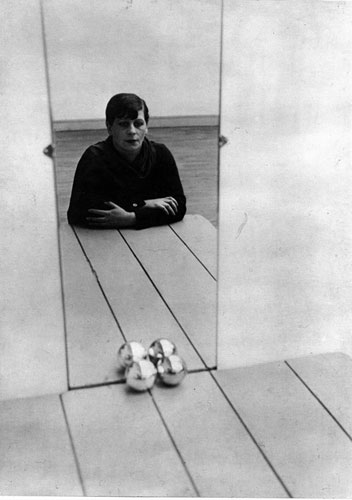

Her advertising work, as well, introduces this dislocation or dissociated space in witty and creative interpretations of the products they depict. In work for Jeanne Lanvin perfume, we see that the reduplication of one perfume bottle in two mirrors inclined toward each other and turned slightly toward the camera produces from one bottle a string of beads (fig. 4). Yet, the edge of the final mirror reflection chops one bottle-bead in half, emphasizing that this is illusion, thus making the string-of-beads joyfully decipherable to the viewer as one bottle. The pleasure of this image lies in first being fooled and then deciphering the technique. As we have seen, the Henri image consistently flattens space or suggests a depth we know to be illusory. Forming a picture plane which appears unitary in its photographic verism (suggesting the singular shot), Henri fragmented the photographic moment into two dimensional splinters, calling into question how we depend on photographic knowledge as an image of the real. Giovanni Martini asserts that Henri "simultaneously presents a real image and a virtual image, soliciting from the viewer a search for the true identity of the image itself."21 Consistently, Henri played with the concepts of true and false, leaving the viewer neither. Likewise, male and female associations play across her imagery, without any resolution but that of indeterminacy itself. Aspects of androgyny come through most clearly in the self-portraiture. When we see Florence Henri, as with others she photographed in her early work, there is seldom a direct glance at the camera. In fact, except for her commercial work and portraits, we see faces only in reflection, and/or turned from the camera's gaze. Margarete Schall in Mirror, with Door, 1928, is not only reflection only, but her face is averted from ours, towards her mirror plane reflected in the adjacent mirror, which, itself, reflects a door we cannot but help read as somehow symbolic, as though the Schall before us were already departed. Or, perhaps, Schall faces the photographer and camera, who are absented in the picture plane but evoked, as one absence to another, by her gaze. The face of Henri herself, similarly, does not regard the viewer in all the self-portraits save one. Instead, vision is turned into itself, narcissistically, yet the mirrored or reflective plane/s of the image complicates that narcissism, making it unstable or extending the self-absorption to other associations. In the two self-portraits of 1928, Henri regards her own image, yet only the mirror allows us to see her face, so that the mirror of the artist's self-study is condensed into the picture plane itself, and we assume the camera-eye not as someone to whom the artist relates but as an interloper. In her essays, "Jump Over the Bauhaus" and "The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism," Rosalind Krauss presents a reading of the often reproduced self-portrait with the chrome balls (fig. 1). Krauss asserts that Henri's mirror frame within a frame is phallic in shape and in the sense of dominance or mastery that marks the framing or selection process of the camera. It is a claim by the photographer for this supremacy and control accorded to her via photography ("Jump Over the Bauhaus," 109), a remaking of the real into a cultural production ("The Photographic Conditions of Surrealism"). Through Krauss, we can interpret the mirror as phallus and the chrome balls as testicles and assume Henri was making a masculine self-image and that photography itself was for her a Lacanian formation of the self which, as does language for that French linguist, exercises a masculine control and mastery over her environment in the absence of that very thing we miss in the photograph—the subject herself. She is only reflection, having crossed the gap of signifier/signified and landed squarely on the signified side through the magical ferry of that omnipresent speech/image master-of-ceremonies, the phallus. In this light we can consider Henri's bisexuality as one simply of a feminine to masculine inversion, or a woman who wants to be a man, the camera her surrogate penis. This reading becomes problematic, if we take another look at this "phallus." In a most un-phallus-like manner, it introduces depth. The "phallus" allows us to see further, behind, within, to the dead stop of Henri centered inside it. It expands to include a room, the photographer's self-regard. It's a roomy "phallus." Not only is depth uncharacteristic of the Henri image, it's definitely uncharacteristic of the phallus. To be a symbol of power and dominance, the phallus must be, first of all, opaque, and, most importantly, solid. The Lacanian phallus does not reveal itself; it operates under concealment, being akin to unconscious drives, not to self-revelation. What's here, I propose, is as much, if not more, a vaginal image than a phallus. The depth the mirror provides leads us to the female subject, squared-off within this channel, hands folded, calmly regarding her image. As though her vision could give birth to herself, Henri sits, a locus and a womb, staring down the perspective lines. The chrome balls, like two eyes, double themselves in the mirror reflection. Furthering discussion of reflectivity in this self-portrait and in other Henri images is Carol Armstrong's "Florence Henri: A Photographic Series of 1928: Mirror, Mirror on the Wall." Armstrong picks up on the vaginal associations of the image, analysizing them with terms from Lacan's heretical pupil, Luce Irigaray. The billiard balls of the still lifes suggest eyeballs to Armstrong, and she metaphorically extends the chrome balls of the self-portrait to that of specularity itself. Their reflectivity underscores the Lacanian mirror stage of self-identity fetishized in reflection and the resultant psychic complications that occur (Armstrong, 225). The balls and their reflections, as well as Henri's reflectivity in general, substitute the internal doubling of the camera and photographic process for the more typical external sight of the machine as phallic bodily extension (226). Here, we find the typically masculinized metaphors of photography appropriated to the female body and its symbolism. Reduplication associates cameras, prints, and the biological processes of femininity, and in Armstrong's reading, this places Henri's photography not within the tradition of an exterior vision positing an object but within an interior or inverted vision, so that the object is the original subject, and both the nature of objectivity and subjectivity are questioned. Armstrong associates this with Irigaray's invoking of the speculum as a "feminine aspect of the mirror stage" (226).22 For Armstrong, however, Henri's specular/speculum is not quite enough to make of her work a success. The photographer still relies upon traditional significations of mirror and femininity, and, so, her project of de-gendering, which Armstrong assumes is her goal, is not thorough but incomplete. The two positions of Krauss and Armstrong, superficially oppositional, are most useful, I believe, combined, for Henri is playing fast and loose with masculine and feminine symbols. She provides for them both and maintains the traditional significations of both, yet she supports neither fully. As a photographer conceptualizing androgyny, Henri wanted to create not a degendered space but a gender-enhanced one of multiple and seemingly mutually exclusive meanings. Only avant-garde based spatial renderings could make the "room" for such a complicated concept. She posed both masculine and feminine signifiers in a spatial field which emphasized their motility and destabilized their concrete significance, a space for the play of meanings of an artist who wished to see herself, as befits her bisexuality, a double creature. In Self-Portrait Lying on the Drafting Table, 1928, Henri appears in the act of her own construction.23 Let us compare this to the 1928 male portrait (possibly of a man named "Charly")24 next to a mirror and drafting table, which associates the structure of the male body to architecture and culture. Perhaps in these prints, Henri was employing binary gender opposition of passive object versus masculine presence. Yet, this interpretation falls apart when we consider that he's wooden, resembling a marionette, evidently a creation suiting Henri's composition, and one that seems no more capable of constructing himself than is the table in front of him. As in a Léger painting, this man is all mechanism, a reduced field that indicates "the erect." Henri, by contrast, lies on her drafting table, regarding herself and the viewer/camera simultaneously, as though she were her own product, Pygmalion-like, come to life. While the association with Pygmalion is a highly traditional view of woman, the difference here is that the creator is she herself, visualizing/drafting her own image. In Self-Portrait in a Masked Frame, 1938, Henri is the reflection itself, popping sculpturally out from the planar surface of the mirror, as though she were Alice peering back through the looking glass. In Self-Portrait Seated at Table, also of 1938, Henri includes no mirror, but, rather, a window out of which she gazes in reverie. On the left side of the image, however, is the double—a whitened area which appears to include part of the table which is cropped by the right hand side of the frame. There's also the suggestion of a window frame that's also cropped off the right and, further to the image center, an exterior area. Henri is giving us her view, inverted from our right side, where she stares, to the picture's left side, the side towards which she is turned. As the mirror inverts, so does the presentation of view and viewer in this witty double-play on our view of a viewer who presents a laterally-correct view of what she sees as well as herself seeing it. In a perhaps apocryphal story in Camera magazine on Florence Henri, which appeared in 1967 on the cusp of her rediscovery, an anonymous writer relates how Henri began to photograph after gazing into a mirror and, seeing her friend's camera equipment, asking how she might capture her mirror image.25 This article, though marred by biographical inconsistencies, strikes a plausible note. Henri was at that time in a slump, unable to paint. An independent, bisexual woman, she had learned to be resourceful, having been at an early age, motherless, fatherless, without a permanent home or locale, and, eventually, she was declared officially "stateless." Once before she had completely reinvented her life—her switch in Berlin from music to painting. Now, after the Bauhaus, another reinvention demanded itself. Mirror photography provided the narcissism that allowed this recreation. The planes of reflectivity allowed Henri to eliminate time, space, and environment, leveling the field of representation so that, rather than personality, it could reflect a woman's act of making culture signify. Within Henri's imagery are feminine and masculine signs, but the fractured space, the unreal sense of perspective or location, the illusions upon illusions, and the absence of one photography's chief fortés, temporal detail, place these images within the primordial or timeless time. The signs then become markers for the pathways of associativity. In themselves they carry little import. In other words, Henri's fruits, dishes, wisps of hair, her chrome balls, and empty stares never rise to the highly cathected state of fetishes. Because they are constantly subordinated to Henri's confusing, a-spatial compositions, they loose their claim to an elevated status in themselves. Henri's symbols, never more than images, siphon strength from the photographic claim to truth, all the while exploiting its realism. Between photography's document and the mirror's alternative door lies the Henri photograph, a being-in-the-world, but what world it is impossible to say. The masculine and feminine signs were important to Henri, and she wanted both, while at the same time she wanted neither fully, which is why she made them consistently unstable. With this in mind, I wish to turn to Virginia Woolf's A Room of One's Own, written in the very year Henri's mirror photography began, 1928. Let me say at the outset of my discussion I think it highly unlikely that Woolf and Henri had any contact. It is not a matter of influence, here, but, rather, something in the climate of that time that circulated in Bloomsbury, the Bauhaus, and Paris. By reading between Woolf's text and Henri's photographs, I propose that their climate privileged a conception of androgyny as necessary to the creative woman. The very construct of woman as artist was, in social acceptance, rather new. Twin constructs, then, androgyny and the creative woman aided each other, from the Weimar's "New Woman," to Bloomsbury's debates on sexuality, to the Left Bank avant-garde.26 I will make a brief comparison between these related worlds through the work of two women, strangers, who took mirrors and turned them against their constricting symbolism, who grappled with the problems of how to be a serious artist (and taken seriously) with precious few female precursors. In the same year, Woolf and Henri took up the mirror, and despite different languages and media, used it to assert their right to claim an art and desire of their own construction. In Woolf's words, such works "are not single and solitary births; they are the outcome of many years of thinking in common, or thinking by the body of the people..." (68-69).

Woolf wrote her by-now classic pair of essays for two lectures at arts societies composed principally of young women. It is, therefore, her counsel to them, as young writers. By using the motif of women with mirrors, as old as the manufacture of mirrors themselves, she takes up a traditional theme and turns its weapon against its progenitors. According to the author, patriarchy systematically denies women their powers, creative and otherwise, and reserves for them the role of agrandising men, or, at very least, serving as their glass, granting the male a superiority by way of default in not being a woman:

And:

As Woolf continues to recount the rather dire straights in which the female author found herself prior to the twentieth century, she cites how literature revolves around the desirable woman, or muse, while women by the common law of England were literally beaten—with the sanction of the state—into submission. "Imaginatively she is of the highest importance; practically she is completely insignificant." (44-45) It is just this imaginative realm, given to the created woman, that Woolf wants for the creative one. Not "the natural inheritor of...civilisation, she becomes, on the contrary, outside of it, alien and critical." (101) She becomes, then, civilization's double: doppelganger,

antithesis, mirror, anti-mirror. The mirror turned inside out is

the one that accuses, that threatens vanity, and collapses "civilization."

Strange, composite creatures emerge from this mirror, hence the

mirror mythology of Dracula and Medusa, asexual or bisexual creatures.27

Neither can see him or herself. This is precisely the problem of

the female artist on the cusp of twentieth century modernity: she

cannot see herself, yet she very much needs to. Perhaps this was

what Woolf intimates when she suggests at the conclusion of the

essays that the writer needs to be androgynous, that she use "both

sides of her mind equally," for "Poetry ought to have

a mother as well as a father." (107) In the permissive world of the Bauhaus and Paris in the '20s and '30s, Henri located a potential space for this fusion of what until her time had been oppositional. Partaking of the mixed masculine and feminine signals of the Weimar Republic's "New Woman," Henri brought such ambiguity to her Bauhaus-inspired experimentalism. Bringing this home to Paris, an "epicenter of freedom for gays,"29 Henri used the mirror as a metaphor for her desire and, by extension, for the confusing, ambiguous, fluid modern world. By yoking seemingly oppositional qualities in her atemporal photographic settings, Henri shows an aggressively destabilized anti-space of mirror and glass, of multiple, contradictory signs, composites of impossible structure, the restless play of creator, creation, masculine, feminine, tradition and rupture. For more information please visit the Galleria Martini & Ronchetti, Genova, Italy. at http://www.martini-ronchetti.com |

|||||||||||||