| |

“ … we are not entirely

matter, nor are we entirely idea … through images, and in images,

we can comprehend opposites, grasp complex relationships, and ultimately

fathom both the interior and the exterior in their entirety. “

Roland Fischer, Kunstbunker, September 24, 1995

|

|

|

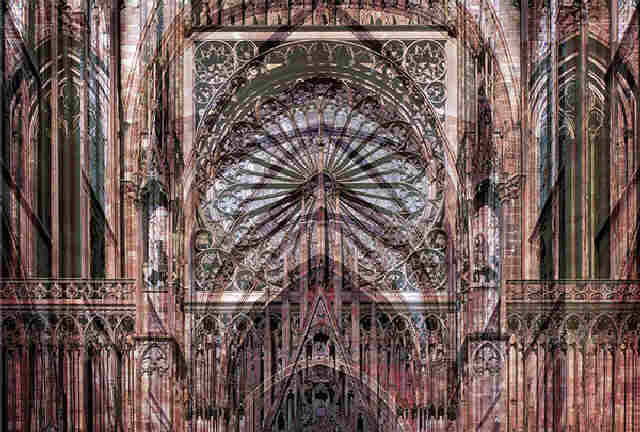

Roland Fischer, a key figure in contemporary

German photography, had his second solo exhibition in the United States

at Von Lintel & Nusser Gallery

from September 6 to October 6. Well known for his monochrome explorations

of portraiture, this show of ten large-scale photographs included

the facades of gothic cathedrals and corporate high rises, buildings

of archetypal recognition. Fischer’s presentation of the gothic

with the modern is hardly spurious. The soaring, light-filled skeletal

volumes of the gothic cathedral were sources of inspiration for early

skyscraper designs by Berlin architects in the 1920s and 30s, in particular

Mies van der Rohe’s expressionist glass skyscrapers. This formal

continuity is revealed through Fischer’s superimposition of the

interior of the gothic cathedral with exterior views. In Fischer’s

combination, the stone façade weaves into the erupting forms

of the interior space. The stone exterior dissolves into an array

of geometric forms, reenacting the great transformations in architectural

form precipitated by the construction of the Crystal Palace of 1851,

a building now seen as the earliest precursor of the glass architecture

of the modern office building. The diamond-shaped verticals of the

pointed arches appear to peel open from the dark shell of the interior,

introducing an organic quality of movement into the static iconography

of the cathedral. As the image itself is crucial for Fischer, the

superimposition of interior/exterior opens up new visual territory.

In line with Fischer’s disruption of the stone façade,

Monet declared, regarding his Cathedral series, that “everything

changes, even stone,” to express his intentions to capture the

shifting conditions of light and vapor that surrounded the façade

of the Cathedral of Rouen.

|

|

|

Fischer’s treatment of architectural form

is related to the formal language of portraiture that he developed

in his Los Angeles portrait series, 1989-91. The faces of these women

float within the blue or black frame of the customary suburban swimming

pool, a monochrome color plane with almost mathematical characteristics.

Freed from any personalized identification such as fashion, jewelry

or social context, the women’s individuality recedes while more

universal qualities show forth from their unadorned flesh-toned faces.

In similar ways, Fischer engages the facade of the building -- frontally,

sometimes framed against the stark blue sky and often completely isolated

from the local context of surrounding buildings. He rarely identifies

the building by name, preferring to leave the photo untitled with

only the name of the city as an index of place. What interests Fischer

least is the documentary aspect of photography. Instead, he captures

the flat planar quality of the modern office building as a purely

visual effect associated with the glass curtain wall, its imposing

height and reflective surfaces. The planarity of the façade

also refers to the flatness of the photographic image. In certain

photos, Fischer goes further by cropping to the boundaries of the

building’s façade so that only the vertical and horizontal

lines of the windows and structure remains framed. The overall visual

effect of this rectilinear treatment recalls the linear enclosures

of Mondrian, an artist who was both inspired by and responsive to

the architecture of the city. Fischer’s photographs of the modern

office building come close to releasing the photographic subject through

the color and line of pure abstraction. He uses the digital imaging

process to transform the photographic image into a starkly abstract

image, in order to “correct’ the waviness that results from

the steep viewing angles required to photograph tall buildings. The

monotone colors and bold lines of Fischer’s digitally-edited

photographs share certain visual elements of abstract or color field

painting, yet the distinctive surfaces of photography always remains

a prominent aspect of the work.

Photography’s move towards abstraction derives from a conceptual

narrative related to the social and cultural context of global capitalism

and the qualities inherent in digital production. New German photography

exhibits a strong fascination with surface, with rectilinear geometry,

with primary colors and shapes, with smoothness and evenness that

were the central preoccupations of modernist painting a century earlier.

Fischer’s architectural photos are monumental in size, most measuring

between 5 and 8 feet in length, the size constraint related to the

print limitations of the C-Print created from a digitally-produced

negative. The trend in contemporary German photography towards larger

formats is yet another direct engagement with abstract painting. Certainly

the lingering drive to legitimize photography as a fine art has also

certainly contributed to the oversized formats of the last decade.

An abstracted image invites a larger format, as it can be viewed close

up or far away and still make visual sense. It also heightens the

visual impact of color and line. Photographers first made the leap

into oversized formats during the heady art market of the 1980s, a

period during which Roland Fischer as early as 1980 and later Thomas

Ruff in 1986 first used oversized formats to show their portrait series.

The effect of the larger scale on content and image created a sensation,

and became the norm thereafter for other German photographers such

as Thomas Struth, Axel Hutte and Andreas Gursky. Fischer handles the

large format in the same way used as the Dusseldorf group, placing

white margins around the entire image and laminating the face of the

print to Plexiglas. The glossiness of the photographs self-consciously

presents the branding features of corporate capitalism, a brash, superficial

style that Fischer closely associates with Americanism.

|

|

|

Architecture has long been the subject of photography,

originally due to the requirement of long exposure times, and later,

when picturesque views of cityscapes and the American skyscraper became

the norm. The skyscraper’s soaring vertical lines, glittering

steel frame and reflective glass façade appear tailored to

be pictured in a photograph. The contemporary office tower and the

rectilinear facades of corporate architecture also provide ideal subjects

for photography, a medium that is nothing but an exact recorder of

distinct volumes in space. In terms of German photography, Bernd and

Hilla Bechers’ documentation of industrial architecture through

a typological model provided the basis for new encounters with the

city’s built form for the fresh wave of photographers emerging

from the Kunstakademie in Dusseldorf. Clearly Fischer draws upon the

same imagery and architecture of corporate capitalism that has fascinated

both painters and photographers associated with “Corporate Realism.”

What differentiates his approach is his willingness to bridge the

stylistic distances, in this show for instance, between the Gothic

and the Modern, laying bare the roots of architectural abstraction

through the contemporary logic of the digital image. In Fischer’s

hands, the smoothness and precision of the digital image ultimately

call attention to the reproducibility of architectural style through

the manipulation of images and surfaces of the modern city.

Author's

Bio>>

|

|