| |

|

|

Fig. 1: Talbot. The

Milliner's Window

|

To take an inventory implies accounting for one's

possessions and listing objects in relation to their identity as

expressions of and testaments to ownership. Most often the owner

or possessor of an inventory is a merchant or storekeeper, but an

inventory may also be a formal list of the property of a person

or estate, a tally of personal traits, aptitudes and skills, or

an evaluation "of one's life and accomplishments." 1 Taking

an inventory, in a sense, is not so very different than taking a

photograph in that each produces a testimony that acts as a marker

of objects in "possession" for a certain duration, whether

that time is a lifetime or the time of exposure. The photograph

as an inventory is a notion which begins with photography's own

beginnings in the work of William Henry Fox Talbot, for whom photography

itself was in part an inventorial activity. In the following discussion

I will focus on the idea of the "inventorial photograph"

2 and its function in Talbot's work. The term "inventorial

photograph" may be understood as a photograph which records

not only possessions, but details and tonal

differentiations. In a sense it is the photograph as "secretary

and clerk" 3 which Charles Baudelaire, twenty years later,

would deem the acceptable arena for photography. However, I will

argue that even this diminutive function of a photograph as "hand-maiden"

is not limited to the realm of pure practicality, but serves to

open up the medium as a site of comparison for objects and natural

phenomena. It is a space to understand a photograph as a visual

grid of temporal-spatial dimensions, and as a testament to lived

experience. In other words, the inventory is not an end but a means

toward understanding photographic structure. My intention is not

to claim that all photographs mimic an inventorial function, but

rather to borrow from the practice and individuality of history's

first photographer in order to further problematize the mechanics

of photography; in essence, a kind of structural exercise in complicating

the inventory of functions and definitions which constitute Photography

as a medium. I will look at Talbot's inventorial photographs of

specialized objects such as glass and china vessels, figurines,

books, and hats as a case study for investigating the relationship

between inventory-taking and the taking of photographs.

As Carol Armstrong has extensively discussed, Talbot's

experimental method of photographing was largely influenced by Sir

John Herschel's natural philosophy as a comparative and accumulative

system of learning. In his Preliminary Discourse, Herschel

delineates that "the first step toward understanding is to

accumulate a sufficient quantity of well-ascertained facts, or recorded

instances, bearing on the point in question. Common sense dictates

this, affording us the means of examining the same subject in several

points of view." 4 With this system in place, based on the

collecting, recording, and comparison of data and viewpoints, Talbot

was inclined to approach, and indeed to inventory, photography itself

as an instrument for the inventorializing of data and viewpoints.

The structure of Photography understood as such (with the guiding

light of Nature) turns images into depositories of facts, recorded

instances, points of view, measures of light sources, chemical combinations,

and times of day - a virtual inventory in and of itself. Every detail

is both recorded in his journal (written in ink) and registered

on the surface of the photograph itself (written in light). But

what does it mean to consider photography as an inventory?; and

how is our understanding of photography expanded when thus considered?

Is it reduced again to its documentary status as record-keeper and

hand-maiden?; or can it be broken down into various inventorial

functions and thereby expanded as a unique medium?

|

|

Fig. 2: A Scene in

a Library

|

Of Talbot's photograph "A Scene in a Library"(fig.

2) on plate VIII of his book, The Pencil of Nature, Armstrong

writes that this image

...is an inventorial photograph, and the object

of its inventory is the author's library, the same library in

which The Pencil of Nature itself surely would be included. Self-reflexively,

"A Scene in a Library" images the world of books into

which the photograph would be inserted, as well as the relationship

between printed text and the photograph's capacities that would

structure such books, and even the manner in which those books

are put together.5

One might expand on this object of a photograph's

inventory by asking the following questions: what other aspects

are built into the inventorial photograph as a strategic format?

What is the structural capacity of Talbot's inventorial photograph

beyond its relation to the printed word? On multiple levels of self-reflexivity,

how does the inventorial photograph (in particular) engage in the

meaning-making and inventory-taking of its author and its viewer

while simultaneously defining the practice of Photography itself?

On this level, Professor Armstrong elaborates: "...Talbot's

instructions ask us to read the photograph self-reflexively, as

an image of photography, defined as a surface full of imaged detail,

deriving from the action of Nature and serving as a temporal index

of the history of the material it records," 6 suggesting that

the self-reflexivity of Photography is both a matter of indexing

surface (or space) and history (or time). Continuing in this vein,

I will consider the intersection between the spatial (the surface)

and the temporal (the historical index) that exists both in an inventory

and in a photograph. Fragmenting the notion of an inventory into

(some of) its shared photographic aspects or parts - and here I

have chosen to concentrate on the inventorial notions of comparison,

display, the grid, and the record or monument of the self - we can

investigate how photography structurally resembles the notion of

inventory.

Inventory/Photography as Site of Comparison

|

|

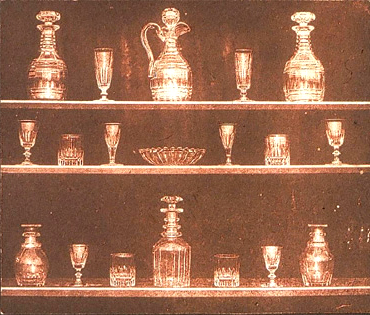

Fig. 3: Articles of

Glass" (Plate IV in The Pencil of Nature)

|

An inventory is a site of comparison. It is a surface

or catalogue on and in which difference and similarity can be registered.

As a system of organizing facts and recording the existence of objects

(or people), an inventory is part of the nineteenth-century scientific

preoccupation, contemporaneous with Talbot's own projects, with

systems of taxonomy and classification in accordance with Comte's

third means toward a natural method, that of comparison. 7

The one after another, one above or below the next, format employed

in many of Talbot's compositions encourages and reenforces comparison

as a method for looking at, not only the objects within the photographs,

but the photographs themselves as a body or site of comparison.

Talbot's "Articles of China"(Plate III in The Pencil

of Nature) illustrates this interest in comparison as Carol

Armstrong again points out. Talbot's caption "commences by

comparing this photograph to a written inventory." 8

Talbot emphasizes that the camera is mute, but fast, and has the

unique ability to depict variously "strange and fantastic"

9 forms all-at-once. Talbot's emphasis, then, is on a

new site (the photograph) as an intersection of space in the form

of surface elaborations and time in the form of instantaneity. In

a sense, not only are shapes, functions, and sizes being compared,

but also time and space. The time and space of writing is compared

to that of photography. The space of the photograph is compared

both to the real time of its making and to the contrasted time and

space of its viewing. A pendant photograph, "Articles of Glass"

(Plate IV in The Pencil of Nature) (fig. 3)is also compared

to "Articles of China" as they are separated by only one

page in his book. Thus glass is compared to china in terms of how

rays of light reflect the form and line of a vessel of differing

manufacture and material. A balanced composition in each image,

encourages the eye's movement from side to side, resting on glasses

of apparently similar function, but with slightly differing details

and shapes. One unique piece in the center, a circular glass dish

with a petal-like, rimmed design holds its place as an axis around

which the eye may spin in the act of comparison, encouraging constant

movement and shifting in viewing.

Michel Foucault famously discusses "Natural

History in the Classical Age" as, in essence, inventories and

sites of comparison: "unencumbered spaces in which things are

juxtaposed: herbariums, collections, gardens....present themselves

one beside another, their surfaces visible, grouped according to

their common features." 10 Foucault continues to

emphasize this dynamic writing that: "from the seventeenth

century there can no longer be any signs except in the analysis

of representations according to identities and differences."

11 Photography, then, as a branch of this history of

juxtaposition, and as a practice based in scientific pursuits, makes

its debut through Talbot as a comparative medium between the photograph

and Nature, between objects, between scenes or individuals within

one image, between photographs themselves, and between the spaces

and times of production and consumption. A photograph by Niecephore

Niepce, "The Table Setting" (c.1827), considered by many

to be the very first photograph, is worth looking at as perhaps

an initiator (and potential example for Talbot) of Photography as

fundamentally a site of comparisons with its objects of various

shapes and sizes: spoon, knife, wine glass, bottle, pitcher, bowl,

etc., each producing a different shadow, tone, or highlight. Talbot's

"Tabletop" of 1840, as a similar still life subject and

arrangement of "facts of light" on various objects, highlights

this comparison and perhaps suggests Photography's "nature"

as one of comparisons.

Inventory/Photography as Display

Secondly, an inventory as a record of collecting and comparing assumes

the application of a system of difference and resemblance and as

such demands a certain dynamic of display, a dynamic which requires

both a displayer and a viewer. Talbot's example of "The Milliner's

Window" (not included in The Pencil of Nature) (fig.

1), allows the display dynamic to operate on various levels which

overlap with the territory of comparison, of the grid, and of the

testament to the self, thus also pointing to the artificiality of

the divisions I have outlined here in the breakdown of inventory

for the sake of argument.

The title "The Milliner's Window," automatically

evokes one of the most common scenes of display, the shopkeeper's

window or showcase. It is only an evocation however because of the

title's status as make-believe. A grouping of ladies' bonnets is

presumably arranged for display and eventual purchase. A many-tiered

scenario is played out in which the title suggests a shop window

where these hats are for sale, available for a price. The viewer

is free to peruse the shapes and styles, the textures and details.

She may imagine her choice and its cost. Yet we know from letters

and other background material on Talbot that the actual scene of

this photograph is that of an arrangement of bonnets out of doors

at Lacock Abbey, all belonging to Lady Elizabeth Feilding, Talbot's

mother. The title is one of fancy supplied by Lady Elizabeth, establishing

her, in a sense, as one of the authors of the photograph. For Talbot,

we might assume, the essential idea was to set up a display of objects

as specimens upon which light would act and where the photographic

result itself is also a specimen that would display the camerawork

of detail and simultaneous representation. "The Milliner's

Window" is thus a virtual inventory of the narratives or subjects

which are able to coexist within the space of a single photograph.

It is a make-believe display of a fictional character's shop window,

a mother's display of her possessions as aspects of her person (she

owns the bonnets), a photographer's display of the range and ability

of his craft as a surface inventory of details, shadows, and highlights,

and a son's display of his own heritage and of his mother's influence

and indulgence.

Peter Wollen writes that "visual display is

the other side of the spectacle: the side of production rather than

consumption or reception, the designer rather than the viewer, the

agent rather than the patient" 12 However, in relation to "The

Milliner's Window", I would argue that the visual displays

announced by the photograph and its title engage both sides of the

spectacle, both sides of the photograph, that of the two designers/producers

and their counterpart, the viewer/consumer. Each side of the photograph

engages in the production of meaning and becomes enmeshed and interwoven

into the subject matter of the image as display.13

In keeping with the parallel between a photograph

and an inventory or collection of details and objects, we might

look to Susan Stewart who writes that "the collection...compels

the consciousness of the observer to enter into the consciousness

of the collector" 14 I would argue that this notion mirrors

Photography, as the consciousness of the viewer and of the photographer

enter into a private, visual contract of meaning production by which

subjectivities are enmeshed and contested, collapsed and discerned.

"The Milliner's Window", then, provides an example of

the meshing and overlap of both subject matters and subjectivities

inherent in Talbot's photographs, and metonymically, in photography

as a medium. One hesitates, however, to introduce the subjectivity

of the viewer into this incestuous brew of claims already complicated

by the narratives of mother, son, fictions, and facts. But, of course,

the viewer is introduced as both the imagined (by mother and son)

and the actual audience or "believer" of the scene as

shop window. The viewer is therefore implicit in the playful production

of the photograph as both viewer and customer. The viewer incorporates

her own more removed subjectivity by stepping into the viewing position

of the author/photographer, but is free to provide her own interpretation

of and identification with the given scene. The viewer is compelled

to relate the photograph back to his or her own subjective experience.

An entire inventory of possible meanings, intentions, and personal

histories is collapsed into a single image.

This photograph, temporally removed from its moment

of production, assumes a many-times-removed identity today as a

souvenir of Talbot's own heritage, relating both photography and

what it depicts tautologically back to his own person. As an index

or residue of a lived experience (or lived experiment, in Talbot's

case), Talbot's photographs act like souvenirs. Susan Stewart, in

her discussion of the souvenir, writes that "...the memory

of the body is replaced by the memory of the object, a memory standing

outside the self and thus presenting both a surplus and a lack of

significance..." 15 She continues: "The presence of the

object [here, both the photograph and the bonnets themselves] all

the more radically speaks to its status as a mere substitution and

to its subsequent distance from the self." 16 Like the souvenir

on display, both the inventory and the photograph serve as markers

of memory, makers of memory, and substitutes for the display, the

event, the life itself, an idea to which I will subsequently return.

Inventory/Photography as Grid

"...The organization of the collection itself

replaces time. And no doubt this is the collection's fundamental

function: the resolving of real time into a systematic dimension."

-Jean Baudrillard 17

An inventory is comparable to the format of a grid.

The grid, as a common twentieth century format for displaying, organizing,

recording, and inventorying goods, images, data and details, is

the manifestation of recorded facts onto a two-dimensional surface.

It is, loosely according to Webster, a system of reference, of coordinates,

or a framework for the storage of information. 18 The photographic

surface itself, like a grid,

may be seen as an abstracted, flattened, quadrilateral inventory

of marks and punctures, and patches of shadows and highlights which

are compared and contrasted, displayed, categorized and recorded.

Talbot points toward a photograph's ability to inventory objects

and details by organizing his articles in a loose, grid-like format;

one object following the next, one object above or below another,

posed for comparison and contrast. At once multiplied and unified,

his objects are held in place in grid-like, imperfect columns and

rows, signifying their own display value, their artifice as positioned

Nature, and Photography's ability to inventory as such.

|

|

Fig. 4: The Open Door

|

The grid format, as discussed by Rosalind Krauss,

is a twentieth century invention in art, yet its basis is an impulse

stemming from eighteenth and nineteenth century systems of classification

and taxonomy. Where Krauss emphasizes that the grid in Art announces

the surface of a painting or a drawing, it seems to me also that

the nature of photography as a medium of surfaces, in tandem with

its capacity as record-keeper, likewise behaves as a grid. Krauss

explains that "the grid appears in Symbolist art in the form

of windows, the material presence of their panes expressed by the

geometrical interventions of the window's mullions." 19

Talbot, in suggesting the fictional window in "The Milliner's

Window," does not need to supply the gridded panes of glass,

they are implied by the captioned title as an organizing principle

and reference to both format and subject. The idea of the window

thus stands in for photography itself as a format for displaying

and organizing objects, as a framing device, as something with both

surface and depth, and as an instrument of reflection. In "The

Milliner's Window", the idea of window (for as we have seen,

there is not an actual window here, but only a fictional one) stands

in as the photographic framework, whose perimeters become the frame

itself and whose imagined glass doubles as the lens of the camera.

The imagined window provides the gridded framework for both the

subject(s) of the photograph, and self-reflexively, for photography

as a medium. In fact, the metaphor of the window can be seen as

an underlying motif or framework throughout Talbot's entire career.

One recognizes Talbot's references to the photo-apparatus as window

in examples such as "The Open Door." (fig. 4) The open

door, the background interior window, its reflections of light on

the ground, and the centered, window-like framed cut of the photograph

itself constantly refer the viewer back to the camera's aperture

and again to the human eye as both window onto the world and into

the soul. The window motif is picked up again and again in Talbot's

"View of the Boulevards at Paris," his various views of

Lacock Abbey, and in a work which Buckland calls the earliest negative

in existence, "The Latticed Window," taken by Talbot with

the camera obscura in 1835. By depicting and emphasizing in a letter

of the time the camera's ability to re-produce the many square panes

of a window and the whole window at once, Talbot stresses his interest

in the part-to-whole condition of both Nature and a photograph as

represented by a gridded windowpane:

No matter whether a subject be large or small,

simple or complicated; whether the flower-branch which you wish

to copy contains one blossom, or one-thousand; you set the instrument

in action, the allotted time elapses and you find the picture

finished, in every part, and in every minute particular. 20

Talbot compares the camera's ability to a natural

wonder, continuing:

There is something in this rapidity and perfection

of execution, which is very wonderful. But after all what is Nature

but one great field of wonders past our comprehension! Those,

indeed, which are of everyday occurrence, do not habitually strike

us, on account of their familiarity, but they are not the less

one that account essential portions of the same wonderful Whole."21

Krauss writes:

As a transparent vehicle, the window is that which

admits light - or spirit - into the initial darkness of the room.

But if glass transmits, it also reflects. And so the window is

experienced [by the Symbolist] as a mirror as well - something

that freezes and locks the self into the space of its own reduplicated

being.22

A parallel with photography is suggested.23 Photographs,

like frozen blocks of life, lock the self as photographer and the

self as viewer into a visual continuum, privileging the fragment

or cut from reality as both transmitter and reflector of subjectivity.

Even though I am not suggesting that every photograph

may be read in terms of the grid in either Talbot's work or any

other photographer's, the framed quadrilateral cut that photography

makes, its abstraction from and indexing of its referent, its serial

propensity, and Talbot's continuous reference to the window structure,

make this comparison compelling. The photograph, acknowledges its

surface and its literal frame of reference, yet compels the viewer

beyond its scope, just as "the grid operates from the work

of art outward, compelling our acknowledgement of a world beyond

the frame." 24 Each catalogues, inventories and acts as an

index for its referent, substituting for the once-there objects.

Inventory/Photography as Testament to the Self

I have addressed individual photographs (within Talbot's work) as

collections, as flattened, organized objects, details, and marks,

but what of his collection, "body", or inventory of photographs

as a whole? Do they "add up" and if so, what do they attest

to beyond their nature as a "first" in the history of

photography? At the (or rather one) crux of Talbot's experiments

in photography is the desire for preservation; the preservation

of not only histories and collections, views and structures, but

also of the Self. At the onset of his diaristic notes of his experiments

he writes: "The most transitory of things, a shadow, the emblem

of all that is fleeting and momentary, may be fettered by the spells

of our 'natural magic' and may be fixed forever in the position

which it seemed only destined for a single instant to occupy."

25 Talbot's own life, as a fleeting and transitory shadow, is fixed

onto the pages of The Pencil of Nature even if its captions

or text do not disclose his project autobiographically as such.

Talbot had a strong sense of self and of destiny.

From a very young age, at the age of eight, he instructed his stepfather

not to allow his mother or anyone else to throw away his correspondence

with them. If we look to Baudrillard's above quote and consider

Talbot also as collector of objects and images in addition to being

a producer, how do Talbot's photographs materialize as markers of

real time and private dimension? Talbot's original ideation of photography

sheds light on his notion of Photography as a solution for durability,

the kind of durability which outlives a human life. His original

desire was to achieve a fixed image, a fixed record of an object

on paper, more durable than "a mere souvenir." 26 Along

these lines, Jean Baudrillard discusses the durability of a collection:

"the object is the thing with which we construct our mourning:

the object represents our own death..." He continues...."a

person who collects is dead, but he literally survives himself through

his collection, which (even while he lives) duplicates him infinitely,

beyond death, by integrating death itself into the series, into

the cycle." 27 In this sense the collection, or the inventory,

and photography as an act of image collecting and preserving, all

perform the task of monumentalizing or marking the that-has-been

which Roland Barthes discusses as unique to the photograph. In Talbot's

case, his choice of subjects to demonstrate and memorialize photography

simultaneously delineate and memorialize his own existence.

Talbot's photographs (perhaps especially his inventorial

photographs), and his overall project of inventorying the medium,

participate in the recording of the various aspects of his own,

private and public self. Talbot does not directly allude to this

reading of his photographs, however each scene in The Pencil

of Nature points in some fashion back to the person, Henry F.

Talbot. The Oxford College scenes reference a highly educated man;

various scenes and views used to elucidate photography's potential

functions are taken at his ancestral home, Lacock Abbey; the inventory

photographs reference his own collections; examples of ancient writing

point to Talbot as a scholar of etymology and philology; and plant

leaves index his role as an amateur botanist. From this angle, the

book becomes a not-so-veiled self-reflexive monument, not only to

photography, but to a man's life, the importance of his heritage,

and his history, not to mention his making of photographic history.

He could have arbitrarily chosen impersonal subject matter to accomplish

his demonstrations of the potentialities of photography and photographic

illustration, but he chose instead to depict markers of his own

existence, thus formulating an alternative, autobiographical subject

for his publication.

In regard to the "Articles of China,"

we are told by its caption that these are specimens (already a textual

act of genericizing or de-personalizing by way of scientific terminology)

or examples of how photography might record "the whole cabinet

of a Virtuoso and collector of old china...on paper in little more

time than it would take him to make a written inventory describing

it in the usual way." 28 Yet, as we know Talbot to be a gentleman

collector and antiquarian, the details and shapes unique to each

of these teapots, teacups, the lattice basket, the urns, the figurines,

and especially the two china figures in repose on their tiny chaises

(see the photograph of "Lady Elizabeth Fielding on her chaise

lounge" of 20 April 1842 as a comparison), point us back to

their owner and to the nature of these objects as choices, tokens

of travel abroad, or gifts, each with its own specific and unique

physical history (or what Walter Benjamin would call, "testimony")

in relation to the photographer. Each object, like the larger photographic

inventory in which it participates, is a marker of memory, the author's

memory: this pitcher was perhaps a Christmas gift from mother, that

bowl was a wedding present from Kit, this urn marks my first trip

to Tuscany, etc. Each object in its own right and the collection

as a whole perform as an index to the aura of each piece's physical

objecthood and the collective aura, or sum total, of its possessor's

once-lived life.

In addition, by concluding The Pencil of Nature

with a reference to the values of portrait photography ("What

would not be the value to our English Nobility of such a record

of their ancestors who lived a century ago?"), 29 Talbot underlines

his book as a "noble" self-portrait within and alongside

its more scientific and experimental functions. As heirlooms, articles

of glass and china, statuettes, and hats, etc. function, like a

photograph, as objects through which to pass on important information

about family events, heritage, and occasions. Although not made

explicit by Talbot until the end with his suggestion of the photograph's

value for future generations to see their ancestors, the conjunction

between such objects of inventory and the inventory kept by photographs,

seems of vital importance to his project. It is almost as if the

trace of memory (in the form of preservation, evidence, written

description, inventory of precious objects, and recorded details)

underlines Talbot's entire project. It is the need to make a durable

imprint, to fix something so that it may be remembered and seen

that is photography's both possible and impossible task.

Talbot fuses his own identity with that of photography,

thereby proving the priority of his discovery in relation to Daguerre

and also demonstrating (even if un-self-consciously) a new type

of subjectivity unique to photography, that is, a subjectivity not

only bound to the authoring of an image, as in painting, but one

which collapses the subjectivity of author and reader, and collapses

at times the author and the objects he photographs. Photography,

from its Talbotian inception, then, is not only a natural recorder

of scientific objectivity and authenticity, recording the traces,

and markings of Time, of wear, of ownership, etc. but also a record

of subjectivity and artifice, of the hand that set the stage or

the eye that chose a scene or a view over and above all others.

My essay concludes with the following questions

which remain unresolved and speak to the, as yet and perhaps permanently,

unresolved nature of my own understanding of the medium: How is

one to remain true to Talbot's photography as a project of scientific

experimentation, demonstration, elucidation of specimens, chemical

actions, shadows, and light and also act as a reader, reading Talbot's

subjective position into the images and simultaneously one's own

position of subjectivity as viewer into the work? In other words,

how does photography suspend and support such different, yet parallel,

activities?; and if The Pencil of Nature attaches "photography

to the spectator over and above the operator," 30 then is it

possible to re-attach the operator in Talbot's case?; and if so,

how does this complicate or compromise a photograph's meaning? Of

what does photography's simultaneity consist?; and is this layering

effect of subjects, narratives, and frameworks, at once multiple

and unified, a quality unique to photography?

Sources>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|