| |

|

|

|

On April 25, 1954, Filmmaker Robert Descharnes

filmed Georges Mathieu at the Paris Salon de Mai painting Battle

of the Bouvines. This huge canvas was meant to re-enact in paint

the drama of a thirteenth-century battle in which Mathieu de Montmorency,

one of Mathieu's ancestors, had played a decisive part. An article

entitled "Mathieu paints a picture" by Michel Tapié

appeared in ARTnews in early February 1955, illustrated with

still photographs from Descharnes's film. This article, in which

Tapié proselytizes for Mathieu, drew swift and negative criticism

from American Abstract Expressionists. In an ARTnews "Letter

to the Editor" of Feb. 22, 1955, Barnett Newman asks sarcastically,

"are there any readers of ARTnews who wish to join me

in sending a pair of sterling silver roller skates, suitably engraved,

to Georges Mathieu so that he may redo his I WAS THERE dance routine

of the Battle of Bouvines into a big Blitzkrieg production?"

Newman goes on to castigate Mathieu for orchestrating a historical

farce in paint, which he calls a "burlesque of immediacy."

To Newman, Mathieu's painting was "clumsy and provincial work"

that was nonetheless sure to "have the Rockefellers, the Burdens,

the Harry Guggenheims, and the Jock Whitneys on their knees in admiration."

The critical ire of Newman and other American painters like Clyfford

Still served to stigmatize Mathieu's painting as shallow and self-promotional,

and his artistic persona as silly, theatrical, and foppishly aristocratic.

Such a polemic served to turn public opinion against Mathieu in

the United States which, following World War II, was largely committed

to asserting the cultural hegemony of Abstract Expressionism.1 Subsequent

art-historical analysis of Mathieu largely centers on Mathieu's

paintings; I want to examine how he was photographed.

This essay will attempt to reconstruct the art production

of Georges Mathieu in the early to mid-1950s according to the influences

of the public identities of Jackson Pollock and Salvador Dali. These

two sources, and their appearance in popular magazines such a s

Life, made an impression on Mathieu, who in turn had an impact upon

emerging performance art in Europe. The photographic conditions

of Pollock and Dali's artistic personae, and their mythologization

(in the Barthesian sense of myth) by the mass media, involves a

shift in the representation of artists in photographs following

World War II, and in the manifestation through photographs of the

"personality of the artist" as both actor and mythmaker.

The first part of this essay will sketch the representation

of artists in photographs since the turn of the century through

a close reading of relevant examples. A discussion of the construction

of Pollock's photographic persona by Hans Namuth will follow, involving

diverse sources such as Native American rituals, psychoanalysis,

phenomenological thinking, and photographs of Picasso that aided

in the personification of the "action painter" Pollock

through photographs. Salvador Dali's appearances in Life,

which involved issues of public promotion, performance, and display,

also had an influence upon Mathieu. The impact of Dali's and Pollock's

photographic promotion upon Mathieu constituted an important historical

shift involving the representation of artists in photographs, and

heralded a fundamental change in the way artists considered their

own production and its documentation and promotion through photographs.

Such a change signaled a move toward a consideration of the art

object as a phenomenological record of movement rather than an a

priori form with an interior "essence." The indexical

quality of photography became a vital component in the production

of the artist's persona by capturing the physical trace of the artist,

arresting his movement.2 Not only does Mathieu's production provide

a link from the "action painting" of Pollock and the self-promotial

bravado of Dali, it incorporates issues of politics and national

identity as well. Michel Tapié proselytized for Mathieu much

in the same way as Clement Greenberg did for Pollock, involving

issues of politics and a nationalist identification with a mythic

hero.

A discussion of Dali, Pollock, and Mathieu must

deal with the central role of photography and the dissemination

of photographic images that captured the performativity of artistic

production, and its circulation into mass culture in the personae

of the artist-as-mythmaker. Most often the photographs took the

form of the documentary photograph at the level of reception. Public

consumption of documentary photography was at a new level of cultural

centrality brought about by popular "photo-story" magazines,

with Life leading the way; in many ways, Life represented

the niche television would later fill during the Viet Nam War. Life's

documentary photographs were the primary vehicle for public consumption

of images of the war, and contained an inherent analogical truth-value

that was manipulated by American wartime propaganda. The subject

matter of documentary photographs and their captions were orchestrated

by the photographers to constitute a particular theme, subject to

the magazine's and the government's approval, but the public was

not made aware of such artifice. Thus a certain amount of deception

was involved, playing upon the belief of the public in the truth-value

of the documentary photograph.

|

|

|

To understand how Mathieu's artwork is influenced

by the photographs of Pollock and Dali, we must first trace how

artists had been represented in photographs earlier in the century.

Analyzing such a lineage will establish certain tendencies which

influenced the decisions of the photographers of Dali and Pollock,

and the way in which these photographs may be read. Edward Steichen's

1901 photograph of Rodin (figure 2) is an exemplar of how artists

were depicted in the first decades of the 20th century, and set

the

unofficial standard for subsequent photographs of artists. Steichen

captures the French sculptor in a moment of cogito ergo sum: Rodin

is presented in his studio as the artist/philosopher, "le penseur,"

who cogitates before he creates. The awareness of sculpture as an

a priori form is inherent in Rodin's decision-making; such form

need only be liberated from the mass of stone or breathed life from

out of the vaporous void which constitutes the space of the studio--a

space of quasi-divine creation given a physical corollary by the

analogical nature of the photograph. The vapor in Steichen's photograph

of Rodin's studio may be said to represent the physical manifestation

of Rodin's artistic genius, given physical substance by light, which

draws a link between Rodin's thought, the studio space, and the

sculpture he has created.

Alexander Liberman was inspired by Steichen's photograph

of Rodin, and contributed to what was a growing genre of "artist

photographs." Lieberman photographed Matisse, Picasso, Braque,

and Giacometti, among others. Many of Lieberman's photographs were

published in Vogue and ARTnews in the late 1940s and

50s together with accompanying essays on the artists and their work.3

The photograph of Giacometti entitled Concentration (Alberto

Giacometti in his Studio) of c. 1951 continues in the tradition

of Steichen's Rodin in capturing the artist as the isolated male

genius. Liberman's photograph may be said to embody the visual equivalent

of Jean-Paul Sartre's characterization of Giacometti in "The

Search for the Absolute," written in 1948. Sartre considered

Giacometti to be a sculptor who worked "outside of history."

What must be understood is that these figures,

who are wholly and all at once what they are, do not permit one

to study them. As soon as I see them, they spring into my visual

field as an idea before my mind; the idea alone is at one stroke

all that it is... the original movement of creation, that movement

without duration, without parts, and so well imaged by these long,

gracile limbs, traverses their Greco-like bodies, and raises them

toward heaven. I recognize in them, more clearly in an athlete

of Praxiteles, the figure of man, the real beginning and absolute

source of gesture [my italics]. Giacometti has been able to give

this matter the only truly human unity: the unity of the Act.4

For Sartre, Giacometti's sculpture embodied the

existentialist, transcendental, unitary gesture. Giacometti's "gesture,"

his additive process, signifies for Sartre the appearance of a phenomenological

activity of movement without duration" which creates the "idea"

of man in sculpture. Sartre considers Giacometti's work to be equivalent

to the signification of man in art for the first time, much like

the lines which compose stick figures of cave paintings. The index,

the physical trace of the artist's hand, is a vehicle for the revelation

of the "language" of art which cannot be known a priori,

only experienced in a phenomenological sense.

Giacometti, like Steichen's Rodin, sits in shadowy

profile, his head in his left hand, in a moment of what appears

to be intense concentration. We notice his sculptures and studio

objects readily enough, but what really holds our attention are

the scrawlings and scratches on the wall behind him. These indexical

marks serve as a physical corollary to the unitary gesture Sartre

speaks of, and provide a visual analogy to Sartre's studio as a

"cave" where "primitive" scrawlings adorn the

walls.5 Liberman's photograph of Giacometti does not create an ethereal,

mystic atmosphere like Steichen's photograph of Rodin. Conversely,

physical traces of Giacometti's "existential anguish"

within the clearly articulated space of the studio are focused upon.6

But the conception of the artist as an isolated genius remained

the same, and would affect how the Abstract Expressionists were

photographed.

|

|

|

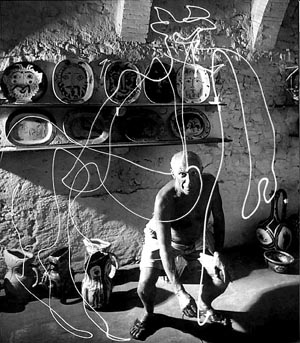

The collaboration between Namuth and Pollock has

its roots in Namuth's knowledge of earlier projects involving Picasso.

Namuth knew about Paul Haesaert's film "Visite á Picasso,"

shot in 1949 and released in spring 1950, in which Picasso paints

on a vertical pane of glass, behind which the camera recorded the

master in action.7 Pollock would probably not have seen illustrations

from Haesaert's film, but he certainly would have seen the next

best thing: Picasso's Space Drawings photographed by Gjon

Mili and not

only widely published in 1950 but exhibited as well at The Museum

of Modern Art. (figure 3).8 Mili's photograph of Picasso captures

him drawing in space with a flashlight what appears to be a bull

or a minotaur. The long exposure arrests Picasso's motions as one

continuous, flowing line of light. The vertical, two-dimensional

plane of the photograph, then, becomes the plane of the canvas.

Picasso wears nothing but shorts and sandals, and has finished his

gesticulations with the flashlight in a balanced, athletic crouch

that emphasizes his physical agility. The light drawing, arrested

for our eye by the long exposure, only exists by the intersection

of photography, just as the gait of a running horse was proven by

Muybridge to have all four hooves off of the ground simultaneously--information

about movement unavailable to the naked eye. Movement through space

and the duration of this movement are arrested and coded by the

photograph. The phenomenological articulation of Picasso's movements

become the sum of their parts; for Namuth's photographs of Pollock,

this meant that the creation of art rests upon the articulation

of that movement within the space of the studio frozen by the camera

and reproduced in popular magazines like film stills.

|

|

|

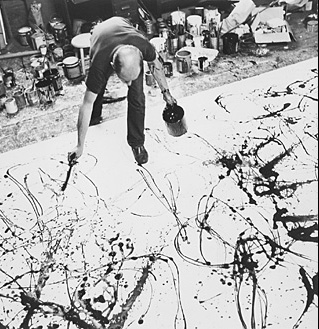

Namuth's photographs of Jackson Pollock (figure

4) were taken in the summer and early fall of 1950 in Pollock's

studio with the intention of mythologizing the already-infamous

painter. Pollock had first appeared in a magazine in December 1947

when Time reported the opinion of Clement Greenberg, critic

for The Nation, that Pollock was one of the three best American

artists.9 Pollock appeared in Vogue in 1948, and twice in

Life. In 1949, Life asked its readers, "Jackson

Pollock: Is he the Greatest Living Painter in the United States?"10

The photographs and text seemed to indicate that the answer was

"yes."11 During this period, Namuth made over 500 photographs,

a black and white movie, and a color movie (with Paul Falkenberg),

all of Pollock at work. These photographs and films are pivotal

to reckoning Pollock as a mythical figure.12 Namuth's photographs

of Pollock moving around the canvas on the floor of his studio served

to confirm the persona of Pollock, which had been developed by numerous

articles and photographs appearing in the mass media.13 Pollock

sought non-traditional artistic sources such as Native American

shamans to engage the space "between the easel and the mural,"14

but still was acutely aware of his position within the larger development

of avant-garde painting, which had been abstracted into model form

by Alfred Barr in 1936.15 In 1947, Pollock stated that "I believe

the time is not yet ripe for a full transition from easel to mural.

The pictures I contemplate painting would constitute a halfway state,

an attempt to point out the direction of the future, without arriving

there completely."16 Due to the influx of influential European

surrealists before or during the war, American artists like Pollock

were forced to reconsider their approaches to art production. Disenchantment

with political strife in Europe and a rejection of what was considered

"decadent" classical aesthetic sources led both the Surrealists

and American artists to search for non-western sources for their

inspiration. The Surrealists's belief in the use of dreams, metamorphosis,

and myth as subject matter for art radically altered the American

artists's perception of what their own role as an artist should

be. Barnett Newman looked at the art of Oceania and the pre-Columbian

Americas, Pollock at Native American sand painting and shamanic

ritual dance. Adolph Gottlieb examined prehistoric petroglyphs,

and Mark Tobey was deeply influenced by Bahai and Zen. Such sources

were romanticized by American artists to a degree; however, the

tropes of such non-Western sources were not utilized to draw attention

to these cultures, but to engage their "primitive power"

as a means of circumventing the outmoded stylistic conventions of

European art.

Through the Surrealists, Pollock developed an acute

interest in psychoanalysis. In 1939, Pollock began four years of

psychotherapy that would aid him in an identification with the growing

interest in the themes of Jungian thought. Pollock identified with

Jung's notion of a "collective unconscious" that all human

beings share at a level of archetypal recognition.17 Jung's postulation

of a "phenomenology of the self" fused tenets of psychoanalysis

and phenomenology into a construction of the "self" (analogous

the to the Freudian ego) whose unconscious was regulated by internal

and external stimuli, creating a "field" of experience

and a response to stimuli of which the conscious ego is but one

part.18 The other part is an "extra-conscious" psyche

whose "contents are impersonal and collective...form[ing]...an

omnipresent, unchanging, and everywhere identical quality or substrate

of the psyche per se."19 For Pollock, Jung's thought seemed

homologous with the mythic subject matter of American Indian ritual,

which involved a process of engaging the tangible world to express

the universal or mythological. Such a process for Pollock involved

a fundamental reorientation of the role of the artist from that

of the thinker to that of the "act-or."

Harold Rosenberg, for example, described this meaning

as the transcription of an artist's inner emotions by means of a

pictorial or sculptural "act." "A painting that is

an act," Rosenberg wrote, "is inseparable from the biography

of the artist. The painting itself is a moment in the inadulterated

mixture of his life."20 Or, again, "Art...comes back into

painting by way of psychology. As Wallace Stevens says of poetry,

it is a process of the personality of the poet."21 Rosalind

Krauss mentions that

In speaking this way, Rosenberg is equating the

painting itself with the physical body of the artist who made

it. Just as the artist is made up of a physiognomic exterior and

an inner psychological space, the painting consists of a material

surface and an interior which opens illusionistically behind that

surface. This analogy between the psychological interior of the

artist and the illusionistic interior of the picture makes it

possible to see the pictorial object as a metaphor for human emotions

that well up from the depths of those two parallel inner spaces.22

For Rosenberg, the picture surface as a locus of

gestural marks demanded that one look at it as a map on to which

one could read the complexity of the artist's psychological condition--a

physical transcription of the artist's inner self.23 Rosenberg's

seminal article re-affirmed Steichen's encoding of the image of

the artist as an isolated genius, but not as "le penseur,"

the inert and bearded demiurge. Rosenberg's "action painter"

moved through his work and through the world, linking the body of

the painter and his genius with the artwork itself. Thus the "inner

life" of the painting is a physical register of the phenomenal

experience of the painter, and a tangible articulation of his psychological,

existential necessity.

Mathieu's work of the early 1950s may be said to

literalize Rosenberg's "Action Painters" mantra. Realizing

the importance of Namuth's photographs, Mathieu was the first artist

to stage live action painting as the subject of photography, and

as a performance before a viewing public. On January 19, 1952, he

had his picture taken in his own studio while painting Hommage

au Marichal de Turenne, a canvas that he consigned to his "Zen"

period, and one loosely in the style of the German gestural painter

Hans Hartung, whose work he respected. The conceptualization of

painting a picture for the camera clearly emerged from Mathieu's

deep admiration for Pollock, whom he considered the greatest living

painter. Through the example of Pollock, Mathieu realized the potential

connection between painting, photography, performance, and the public.24

The documentary nature of the photograph, given world attention

by magazines like Life, carried the content of painting and

the process of performance to the public. Mathieu was the first

to synthesize this connection.25

But Mathieu's Battle of the Bouvines(figure

1) cannot be seen only to operate solely within the dialectic of

Pollock's working method and Rosenberg's action painting proclamation.

His work must be understood within the context of his relationship

with Dali as well. Mathieu and Dali were in close correspondence

in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and it certainly was not lost

on Mathieu that Dali had appeared in Life magazine twice

before Pollock. The Life articles contributed greatly to

Dali's international reputation as a Surrealist performer whose

life and art were largely inseparable. Salvador Dali's first appearance

in Life was in January of 1941 (figure 6), and presented

a "lighthearted" piece, a bit of escapist amusement from

the overbearing presence of World War II photographs. In "Life

Calls on Salvador Dali," Dali is presented as the "eccentric"

houseguest of wealthy Virginia matron Mrs. Phelps Crosby at her

mansion, Hampton Manor, designed by Thomas Jefferson (figure 7).

Dali is completely de-politicized in the text and photographs of

the article; there is no mention of him as an exile forced to flee

Europe, nor of the similar fate of many artists before or during

the war. Dali is described in terms of comforting, harmless, and

solid American values, like "he's nuts about his wife,"

and is "enchanting" to his host, the eccentric European

aristocrat with the wild moustache. Despite the fact that Dali is

boarding with an aristocratic woman and behaves like a wealthy man

who has time to do wacky things like putting manikins in ponds,

he is still presented as a "man of the people"; he is

photographed at the local store in De Jarette, VA sitting around

the coal stove and talking to the locals. The caption accompanying

the photograph of Dali sitting in the store conversing with De Jarette

citizens reads: "In the general store at De Jarnette, Dali

loafs by the stove and leers at his wife while Mrs. Crosby does

her daily marketing. Small, drab, and populated mostly by Negroes,

De Jarnette attracts Dali daily. He likes to look at the cans in

the store, to drink Cokes, and to converse with the bewildered but

fascinated citizens." Thus Dali's eccentric, aristocratic behavior

is presented as accessible to the common man, and by inference to

the readership of Life. Dali's surreal life is presented

as harmless and cozy, a down-home, folksy Surrealism designed to

appeal to the readers of Life.

|

|

|

The second article, which appeared in Life

in September of 1945 (figure 5), was concurrent with the victory

of the Allies in Europe. The issue which included Dali's article,

fortunately for him, was perhaps Life's most popular issue,

containing V-E Day coverage, and the famous photograph of a sailor

kissing a nurse in the celebration at Times Square. News and images

of the war dominated the issue, and tropes of the "support

our boys overseas" variety were dominant in product advertisements.

Dali's self-promotional theatricality is accentuated by columnist

Winthrop Sargeant. The article's title clearly indicates its content:

"Dali: An excitable Spanish artist, now scorned by his fellow

surrealists, has succeeded in making deliberate lunacy a paying

proposition." 26 Sargeant's description of Dali's performative

persona often sounds like British huckster Robin Leach's shills

for "Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous" of early 1990s

American TV: "Dali...is not only a surrealist in paint; he

has acted the part of a surrealist in real life [my italics]

to a point that, at times, seems indistinguishable from actual insanity.

The act [my italics] has been amazingly profitable."27

Sargeant goes on to situate Dali's biography within a sketchy historical

account of the emergence of surrealism within modernism, in tune

with Alfred Barr's linear model of 1936. Dali's successful blurring

of the boundaries between art, commerce, performance, and life would

have an impact upon Mathieu.

In 1954, Dali cabled Mathieu from New York: "need

to continue paranoiac-critical study of Vermeer's Lacemaker

before live rhinoceros stop Arriving Paris next week."28 Dali

explains that his interest in the rhinoceros at this point was not

accidental. Of all living animals with horns, only that of the rhinoceros

is constructed as a perfect logarithmic spiral. The spiral was a

mystical, archetypal form which was engaged by cultures outside

of European cultural history. Dali's search for sources which subverted

the classical tradition of western art due to the trauma of World

War II and the atom bomb led him to Spanish mysticism as well.29

Mathieu's adoption of the persona of Mathieu de Montmorency for

the Battle of the Bouvines parallels Dali's search for non-classical

sources. Robert Descharnes, who filmed Mathieu painting, provides

another link to Dali: also in 1954 he filmed Dali's reconstitution

of The Lacemaker at the Vincennes Zoo in front of a rhinoceros

named Frangois.30

The criticism of Clement Greenberg endowed the work

of Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists with a political agenda.

Krauss aptly characterizes Greenberg's critical position: "Greenberg's

entire critical vocabulary was that of rivalry and of American artists

besting the Europeans, outwitting them in the battle for history."31

In the March 1948 Partisan Review, Greenberg asserted the shift

of "the main premises of Western Art" from Europe to the

United States.32 Greenberg's belief was that The New York School

had "wrested the torch of high culture" from an enfeebled,

faction-ridden Paris which was threatened internally and externally

by communism.33 Tapié, keen to rival Greenberg's apparently

strong critical position, sought to be the same vigorous polemicist

for European painters that Greenberg was for the American Abstract

Expressionists. Tapié employed the lofty, mystical rhetoric

reminiscent of Bruno Taut, Paul Scheerbart and the German Expressionists:

Everything has been called into question once more

since that cascade of revolution going from Impressionism to Dada

and Surrealism: we are beginning to realize what that means, and

at which point this total review has caused the epoch in which we

live to be equally thrilling. After centuries, if not a millennium,

during which conditions evolved so slowly that in the normal rhythm

of life, chance could not be perceived, and in which artistic problems

(even ethic-aesthetic ones) were safe...an entire system of certainty

has collapsed. 34

Tapié engages the tropes of Abstract Expressionist

promotion (existentialism, masculinity, myth) to situate Mathieu's

production. Tapié describes the painting of the Battle

of the Bouvines as one "in which [Mathieu] has been able

to gesticulate to paroxysm the quintessence of his inductive myths."35

But Tapié claims that there is an absurdist, neo-dada element

to Mathieu's aristocratic persona echoing that of Dali: "Mathieu

regards everything as totally absurd, and shows this continually

in his behavior, which is characterized by the most sovereign of

dandyisms."36 The intention of this absurdity is to willfully

"thrust the spectator forcibly outside the absurdity of the

humdrum and the mediocre and into that atmosphere of dynamic power

the creative-destructive side of which was so masterfully revealed

by Nietzsche."37 With such lofty, absurdist rhetoric and references

to Nietzsche, it is not surprising that American artists and critics

misunderstood Mathieu's intentions. The construction of his persona

drew from tropes which were anathema to the personae of the pragmatic

American Abstract Expressionist painters.

Mathieu's reception in Europe was mixed, but was

acknowledged by Yves Klein as a mentor and fellow monarchist.38

Klein's notorious Leap into the Void of 1960 which purports

to document a single, spontaneous, risky leap into space, demonstrates

his debt to Mathieu in terms of staging his art for photography.

But Klein's debt to his mentor is also conceptual and intellectual.

Klein's attention to risk, spontaneity, speed, and improvisation,

carried out in his "living brushes," and other work, echoes

Mathieu's thinking: In Mathieu's "Towards a New Convergence

of Art, Thought, and Science," published in 1960, he outlines

what he terms the "phenomenology of painting": "1.

First and foremost, speed in execution. 2. Absence of pre-meditation,

either in form or movement. 3. The necessity for a subliminal state

of concentration."39 Mathieu was also recognized by the Viennese

action artists, who acknowledged his performance in Vienna April

2, 1959, at the Theater am Fleischmarkt, as significant in their

move into action.40 Traveling to Japan in 1957, Mathieu and Tapié

were warmly received by the performance-oriented Gutai Group as

colleagues in exploring a new aesthetic direction.41 In front of

crowds of people in Tokyo, Mathieu painted twenty-one canvases in

three days, including a fresco approximately 45 feet long.42

The September issue of Time magazine covered the event extensively.

Mathieu had come full circle, gaining a major magazine article like

Dali and Pollock, captured forever in words and photographs as an

internationally recognized artist who acts.

Sources>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|