| |

|

|

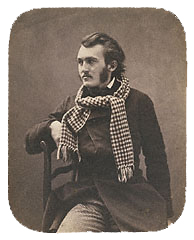

Nadar, Ernestine, 1854-5.

Salted paper print. 24.7 x 17.2 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum,

Malibu.

|

"Nadar" was the name offered by Roland

Barthes to his own question as to who was the world's greatest photographers1.

The question runs beneath an image he claimed was "one of the

loveliest photographs in the world…a supererogatory photograph

which contained more that what the technical being of photography

can reasonably offer."2 The image is of a white

haired woman with soft dark eyes, who through dark velvet folds,

lifts a hand obscured by an cream colored eyelet- edged sleeve to

gently raise a sprig of violets to her mouth in a gesture so tender,

so private, it resembles more the action of a kiss or a breath than

a posed portrait. In the text, Barthes identified the photograph

as being "of his [Nadar's] mother (or of his wife-no one knows

for certain)."3 This ambiguity allowed Barthes to

view the image through his own bereavement-the death of his mother-the

event that propelled him to search for the ontology of photography,

a medium he declared to be structured by loss. That Barthes included

a portrait by Nadar in a book on photography is hardly surprising,

as Nadar has generally been considered one of the premier portraitists

since the time he opened his studio. It is also not surprising that

Barthes would chose to project his own longing onto this image,

creating a narrative suited to his own purpose as the book is a

personal meditation on photography, structured by preferences, or

as he claimed "I like / I don't like."4 The

photograph that inspired Barthes is markedly different from the

images most often associated with Nadar, both in subject, relation

and time.5

Celebrated during his lifetime as one of the greatest

photographic portraitists, Gaspard Félix Tournachon, known

as Nadar received particular renown for his informal photographic

and caricature archive of the cultural generated by his photographic

portraits of celebrated subjects, players of the mid to late Nineteenth

century Paris--"la vie bohéme"-the world in which

he portrayed himself as belonging. Despite the acclaim the primary

benefit was financial, as the majority of his photographs were cartes

des visites commissioned because of his fame. It was through these

quotidian photographs that he was able to support himself and fund

his other projects.

Nadar stated that the goal of the photographer was

to capture the "moral intelligence of your subject - that rapid

tact which puts you in communion with your model...and which permits

you to give ...the most familiar and favorable resemblance, the

intimate resemblance."6 His collodion-on-glass negative

photographic portraits contained detailed views; figures seated

or standing in three-quarter body shots against neutral backdrops.

Like other portrait photographers, Nadar utilized props and costumes,

such as drapery, in his photography, yet as opposed to other contemporary

portraitists, such as André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri

(credited as the inventor of the carte de visite), Nadar's

photographs transmited their information through a minimum of sources.

Attention was directed to the subjects through the simplicity of

the set; instead of employing elaborate backdrops, his subjects

were generally seated, facing the camera either frontally or at

a three-quarter view. Lighting was both natural and artificial,

directed through the use of mirrors to create dramatic shadows,

contrasting light tones against dark to enframe his subjects in

an aura of light, intended to mirror their personal aura. This luminosity

made subjects appear aglow, as if lit from within, an effect amplified

by the intense smoothness of the pictorial surface.

While the props were minimal, the surfaces were

detailed, drawing attention to the intensity of textural details.

The use of props may contain clues to gender roles and identities,

roles that may have been emphasized or dramatized for the camera

in a type of studio performance. The photographs have an aura of

naturalism. The subjects were generally shown in clothing instead

of costumes, which had the effect of amplifying this effect. The

clothing was chosen over costumes so as to direct attention to the

character of the subjects, as constructed through clothing, poses

and facial expressions, versus the theatrical distraction of costumes.

More than anything else, what has been said to characterize Nadar's

portraits was his apparent rapport with his subjects, so as to appear

more as collaboration than as a relationship between client and

businessman or subject and operator. A central question is how this

relationship operates when the client or the subject is a woman.

A portrait is conventionally read as a provider

of information-specific details of the subject, mainly physical,

are reproduction and represented by the artist. Because photography

is an indexical art, the photographic portrait has additional claims

to veracity; it is this very claim that leads Barthes to declare

that "every photograph is a certificate of presence."7

The portrait photograph typifies what Roland Barthes describes as

...a superimposition here: of reality and of

the past. And since this constraint exists only for Photography

...[it is] the very essence, the noeme of Photography...neither

Art nor Communication, it is Reference, which is the founding

order of Photography. The name of Photography's noeme will

therefore be: 'That-has-been,' or again: the Intractable.8

According to Barthes, photography, structured by

the "That-has-been," carries within it information, rather

than meaning. Nadar's photographic portraits, however, are more

than mere conveyers of biographic information, rather, they are

essentially "open works," where a multitude of information

resides in the betweens - in the shadows, the lighting, the folds

of the work such as Umberto Eco describes in The Open Work.9

Yet, in order for the photographic portrait to convey information

about the subject, it must first convey information about the world

in which the subject operates. As Max Kozloff writes in "Nadar

and the Republic of Mind,"

Let's define a portrait as the picture of an

individual or group whose character is either described by social,

ethnic, and class affiliations, or may, in some measure, be invoked

in contrast to them. Sometimes, in the history of the genre, the

"personality" of the sitter has gained the upper hand,

and, sometimes, his or her status. More often the portrait turns

out to be an unpredictable composite image of both.10

In Nadar's portraits of artists, male artists were

generally photographed in clothing intended to present bourgeois

respectability and modernity. Although the clothing was actually

often borrowed from Nadar's studio, it was to have the appearance

of being what the subject had worn to the studio. The same straight-forward

quality which characterized the portraits was applied to the clothing

of the male subject, where nothing was to distract from the physiognomic

appearance of the subjects and their "moral intelligence"

of which Kozloff writes. However, with his feminine subjects, what

was emphasized was less their "moral intelligence" than

their physical or corporal presence.

Kozloff writes of Nadar's "republic of mind"

stating that

Nadar's republic of mind can't be said to have

formed any counterculture within the Second Empire, as if it were

simply a question of hip versus straight life-styles. On the contrary,

time and again, his artist characters present themselves in the

severest terms, the most funereal raiment. In an essay on the

Père Lachaise cemetery, Frederick Brown writes: 'Black

broadcloth had always been a flag of sobriety in which Europe's

bourgeoisie draped itself, not with any illusions that clothing

made the man, but, on the contrary, hoping that it would serve

to hide him.' It's a sign of their imaginative astuteness that

Nadar's sitters often seemed to have used the costume of the bourgeois

anonymity to reveal themselves. It became a foil against which

they dramatized, for posterity's benefit, a vision of their own

unique and sovereign identity. Nadar seems instinctively to have

grasped this, in defining just that moment when the face ripens

into characteristic self-assertion, toward which the body also

swells.11

Kozloff's description is revealing on several counts.

First of all, it is telling that Nadar and his bohemian subjects

would choose to adopt the bourgeois uniform. Secondly, one would

assume that Nadar's photographs specifically, Nadar's photographs

of artists, were solely of men. While men do comprise the undeniable

vast majority of the photographic portraits, particularly the portraits

of artists, female artists, such as Sarah Bernhardt, Georges Sand

and Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, were also photographed by Nadar,

with Bernhardt and Sand being photographed several times. Although

these images are generally included in surveys of Nadar's work,

the critical writing about Nadar has neglected to address the questions

of gender difference, the effect of gender on the photograph, or

to clarify how gender was constructed and portrayed. For it could

be argued that Nadar's photographs not only portrayed his subjects

physically clothed as the bourgeoisie, but that his works themselves

were clothed in bourgeois conventions, expressing conventional ideas

of gender and gendered roles. Yet within this bourgeois covering

were ruptures and folds, areas of between, overlaps and divisions

that revealed schisms and disruptions within that order. It is in

this area of gaps and irregularity that his photographs appear to

be uniquely suited to operate because it is through operating in

these folds that the photographs reveal gender difference of late

nineteenth century Paris bohemian and bourgeois culture.12

Through their photographic construction, Nadar's photographs can

be read as conveying the idea that gender itself is a construction,

something adopted or staged through props and accessories or something

put on, like a costume or a painted mask. Gender did play a central

role in how the women are presented, if nothing else, because they

were denied the option of the black suit of the bourgeoisie, that

"flag of sobriety in which Europe's bourgeoisie draped itself,"

that symbol of modernity of which Baudelaire wrote.

As early as 1856 at the Brussels Photography exhibition

of 1856, Nadar was noticed for his 'ravishing portraits of women.'"13

From the beginning of his career as a caricaturist, women artists

were represented in Nadar's oeuvre, as evidenced by the celebrated

Panthéeon Nadar of 1854 and 1858. In his female photographic

portraits, Nadar created a distinction between photographs of women

he considered artists-celebrated women such as Marceline Desbordes-Valmore

and George Sand-who were generally older and members of "la

vie boheème" and whose portraits he exhibited with male

artists, and his photographs of young models, actresses, dancers14

that he exhibited with portraits of children and nature studies.15

A third category can be added to the other two-photographs of his

wife, Ernestine. Nadar's photographs reveal that he adopted different

modes of portraiture for each group, reflecting different concepts

of gender construction and socio-economic position, in addition

to his own relationship with the subject.

|

|

Nadar, Marceline Desbordes-Valmore,

1854. Salted paper print. 19.6 x 14.9 cm, J.Paul Getty Museum,

Malibu.

|

The first group was comprised of portraits of women

artists. Artists such as George Sand (1864) and Marceline Desbordes-Valmore

(1864) were shown dressed as proper bourgeois ladies, and although

they could not adopt the black suited uniform of the male bourgeois,

their clothing reflected and conveyed their status and position

within this class. The frail frame of Desbordes-Valmore is shown

properly attired beneath layers of clothing: patterned scarves cover

her head, a stripped bow is tied beneath her chin in a particularly

infantalizing gesture, contrasting with the refined, dark color

of her dress, whose somberness is interrupted by flouncy white ruffs

at her wrists and on her chest. Her black lace covered hands rest

on her lap, her arms bent slightly, making them pull away from her

body, as she appears to adopts the pose of male artists also shown

seated in such a position. Yet within this rather stiff and conventional

pose, the position and gesture of her hands becomes particularly

interesting. Her right hand rests on a raised leg, obscured by the

heavy fabric of her dress. Beneath the intricate black lace glove,

bent fingers appear, one flashing a gold band, the other appearing

to point to her lap. Her left hand is slightly arched, her first

three fingers more visible, almost fully extended, as the index

and middle finger separate in the form of scissors, one form appearing

to mirror the other. A gap exists between them, an echo of the larger

gap between the fingers and the thumb. In this positioning of her

hands and their placement on her lap, Desbordes-Valmore appears

to interrupt the standard portrait. It is as if her hand appears,

perhaps unconsciously, not only to point out difference suppressed

by the format, but to point to the area of sexual difference, making

a motion of splitting, or separation.16

Generally, the women in this grouping were older

and the emphasis was on character and physiognomy-which was to reveal

their "moral intelligence." This physiognomic investigation

is evidenced by the focus on the lines and forms of Desbordes-Valmore's

face, the bags that form under her eyes, the wrinkles that enframe

her mouth.17 The saccharine quality of her facial expressions combined

with the awkward tilt of her head would inspire Barthes to write

that "Marceline Desbordes-Valmore reproduces in her face the

slightly stupid virtues of her verses."18

What characterized the second grouping of women,

however, was not so much the attention to facial expressions, but

the attention to their bodies. Although the body was hidden beneath

heavy folds of fabric, such as linen or velvet, or heavy dresses

and bonnets, the subject was still read first as a body. Young women,

generally of the theater, such as Sarah Bernhardt, or models, were

often depicted draped in heavy fabrics that they subtly clutched

to their breasts or lay over their shoulder.19 In contrast

to the straight, simple lines of the dark suits worn by the men,

the bolts of fabric formed deep dramatic folds. Although the drapery

provided coverage equal to the bourgeois dress that the older female

artists wore, the drapery is a constant reminder of the nude body

underneath, the interior precariously covered. This drapery was

the opposite of "the costume of the bourgeois anonymity"

that the male artists adopted "to reveal themselves,"

for while the black suits recalled the exterior world, the world

of the modern city, the drapery consciously invoked history and

interiority: interior settings, such as the studio or even, in the

two photographs of Bernhardt, the bedroom, and the interiority of

the nude body beneath the clothing. The vacillation between these

two conditions-that of interiority and exteriority-can be said to

structure these portraits. In addition, it is impossible to view

the drapery without thinking of class-the difference that marks

the subjects of this grouping as different from the everyday clothing-the

bourgeois clothing read as natural-worn by the artists, both male

and female.

|

|

Nadar, Gustave Doré

|

Although Nadar also utilized drapery as ornament

in his representation of male artists, such as Gustave Doré

(1856-58) or Jean Journet (ca. 1855-56), that drapery played a fundamentally

different role in the portraits of male subjects. In the portraits

of Doré, the elaborately arranged drapery rests on top of

the bourgeois black suit, to be read as an individual artistic flourish

literally added to the staid, respectable bourgeois uniform. While

in the portraits of Journet, the drapery framed his body, like that

of a martyr. As Elizabeth Anne McCauley writes

The use of a velvet mantle flowing around a nude

torso, adding mass and visual richness, was less a derivation

of high fashion than a borrowing of the baroque symbolism of genius

and power. By removing the figure from contemporary life, this

framing device focused attention on the face and encouraged comparisons

with Bernini's bust of Louis XIV or a Roman portrait bust, in

which a specific likeness contrasts with generalized, dynamic

drapery....20

At least three of Nadar's photographs of Bernhardt

produced between 1864 and 1865 showed Bernhardt covered in heavy

fabric, leaning on a pillar in poses and compositions so similar

that one could mistake several photographs for multiple exposures

shot at the same session. On closer inspection, differences emerge:

the color of the drapery, the position of Bernhardt's form, her

slightly differing facial expressions and the lighting of the scene.

Nadar's photographs of Bernhardt were markedly different, distinguishing

this series from both Bernhadt's representation in the work of other

photographers and Nadar's other subjects. In the photographs, Bernhardt

was shown immersed in voluminous drapery in Nadar's standard three-quarter

body view. She leans on a truncated column, dramatically draped

in either light or very dark colored drapery, which forms thick

folds and creases around her body. The loose, undulating form of

the drapery is echoed in her free flowing hair that curls around

her face, highlighting her facial features, the focus of the work.

The lighting, which produces gentle gradations of shadow and light

and the smooth, glossy surface creates an overall effect of luminosity

and polish and allows fine details-such as the texture of the cloth,

the tasseled details at the borders, the metal of her earrings and

the gloss on her lips- to be revealed. The goal of the photograph

was not only to portray her dramatic, daring spirit, but to show

that this artistic soul can be most fully and accurately portrayed,

indeed can only be portrayed, through a fellow artist, Nadar.

|

|

Nadar, Sarah Bernhardt, ca.

1864. Modern print from a glass negative. 30 x 24 cm. Caisse

Nationale des Monuments Historiques et des Sites, Paris.

|

The photographs of Sarah Bernhardt are characterized

by their dramatic use of drapery. Although drapery was used with

other women and some men, it is at its most voluminous, most conspicuous

in the portraits of Bernhardt. It is also integral to the meaning

of the photographs as it is in the multitude of voluminous folds

that the meaning of the works reside. The works can be said to be

like the folds, to be between layers in which questions of gender,

social class, art reside. The folds encompass layers of fabric,

between which fall deep shadows, paralleling the world of betweens

in which Nadar and his milieu operated. The folds that were most

prominent in Bernhardt's drapery, significant as the fold can be

associated not only with her portrait, but with Bernhardt, who,

as a woman, transgressed the typical gendered role for women and

operated in a zone of the fold, between artist and muse, between

bourgeois and bohemian, between the male artists and that of the

sexualized and/or maternal body. Her portrayal, with the thick,

almost sculptural folds of fabric, the classical pose leaning on

a columned pillar consciously recall poses associated with the history

of art, although Nadar himself was a firm proponent of modernity,

deriding painters such as Jean Auguste Dominque Ingres for the stale and

sterile quality of their work with its emphasis on line and classical

composition.

Yet the drapery and props cast Bernhardt more as

a muse or model than as a fellow artist. Compared with Gustave Courbet's

Studio of A Painter: A Real Allegory Summarizing My Seven Years

of Life as an Artist, (1854-5), Bernhardt occupies a position

similar to the female model located in the center of the painting.

The woman in the painting stands behind the artist (Courbet), a

figure of silent support with a look of dreamy intent while watching

the artist paint a landscape. She is nude except for a white cloth

she holds to her body, which does not so much cover her as emphasize

her nudity. Her nudity is further reinforced by the crumpled pink

and white pile formed by her dress that lies on the floor in front

of her. The woman's role in the work is ambiguous - she may be a

muse, or divine inspiration, or a model for another work. Like the

landscape he is painting, the woman represents a standard artistic

convention-the nude-that evokes high art. She also can be read as

symbolizing nature, her purity and innocence emphasized by her association

with the boy, the dog and the landscape being painted. Her "naturalism"

is reinforced by her nudity - she does not adopt the clothing (or

artifice) of the bourgeoisie or the Parisian artists gathered around

the back of the canvas, rather, she stands, in a "pure"

state, looking over the artist's shoulder in support of his genius

and the culture he symbolizes.

|

|

Maria, 1856-9 .

|

To say that Nadar presents Bernhardt as representing

"Nature," would be incorrect, but it is important to note

how different her representation is from the male artists and how

much closer the resemblance is to Courbet's nude model or 'muse,'

and Nadar's portraits of the model Maria. Nadar's portraits of Bernhardt

also differ significantly from how she was portrayed by other photographers.

Comparing an 1877 woodbury portrait of Bernhardt by Emile Tourtin

with Nadar’s images, one notices in both series a concerted

focus on material, yet the elaborate volumes of Nadar’s drapery

are replaced in Tourtin by elegant lace, pearls and jewels. Bernhardt's

elaborately flounced white dress, composed of layers of ruffles,

laces, pleats and folds and buttons, thick ropes of pearls dangling

from her arms, her ears and around her neck over a rhinestone choker,

and the large white flower in her hair portray not just a different

image, but a different type of person than in Nadar's images. In

Nadar's photographs, Bernhardt, though shaded, appears more in focus

and physically closer to the viewer by appearing to lean into the

camera, while in Tourtin's image she appears hazy and out of focus,

as if weighed down by the layers of artifice that connote a specific

class. In the Tourtin, Bernhardt lacks a connection with the viewer

(and by association with the photographer), rather she turns her

head at a three-quarter angle, hiding half of her face and focusing

her gaze to the side, out of the range of the camera. In such a

work, what one sees is more an official portrait than a collaboration,

for in Tourtin's image, she is Sarah Bernhardt, the celebrated actress,

more a personality, a successful performer off-duty than an artist.

In such a work, the emphasis is on the external, whereas Nadar attempts

to strip her image of artifice in an attempt to reach the internal,

the core, of her as an artist, and as a woman, by association, the

unknowable "other."

The dialogue between interiority and exteriority

as projected onto the female body culminates with the two photographs

of Maria (1856-9) and Paul Nadar and his Nurse, 1856.

Little is known about the model from Antilles named Maria. In the

first photograph, Maria is presented with her body and face turned

away from the camera, a large portion of her face hidden in shadow.

Her hands are tightly clasped around the drapery to form a closure,

while her arms are crossed against her front as a double barrier,

dramatic, opalescent light which shines on her arms creating a visual

distraction, a diagonal that not only blocks the gaze from her front

but leads the eye to her shoulder and the backdrop. In contrast,

the other photograph is more about exposure. Strongly lit, Maria

faces forward, her arm rests on the back of the chair and her hand

is on her cheek, drawing attention to her face which is turned at

a slight angle and her gaze off-camera. The drapery falls open,

exposing her breasts, which are only slightly lower than the center

of the photograph. The two works emphasize the effects of uncovering

and revealing, and the fine line that exists between the nude body

swathed in drapery and the body exposed when the drapery falls away.

The body exposed, or the interior rupturing the

façade of the exterior also can be seen in the photograph

of Nadar's son, Paul, being fed by his wet nurse (Paul Nadar

and his Nurse, 1856). The bodies of the nurse and the baby are

almost entirely covered by cloth-white bonnets cover their heads

and are tied securely below their chins, the baby is covered in

layers of fabrics and blankets held by the nurse who wears a black

lace shawl overtop of her black dress which primly extends to the

her neck in a white lace collar. Yet despite the excessive covering,

the body emerges in the form of the woman's naked breast, firmly

clenched by her darker skinned hands that she offers to the child

for a feeding. This action creates an opening, a disruption in the

layers of fabric, and the emergence of what is normally hidden and

contained, representative of the interior and the private, becomes

exposed, public, and viewed. This exposure also reveals what ultimately

codes her, not only in terms of gender and sexuality, but also racially

and socio-economically-it reveals her position in Nadar's world.

The last category of female portraiture is reserved

for only one person-Nadar's wife, Ernestine. In these works, the

subject cannot be reduced to distinctions of artist, client, or

model, as she transcends such categories. Instead,her portraits

are characterized by intense intimacy between the subject and the

photographer. Ernestine does not utilize studio props or costumes,

in fact, she appears to have an active resistance to the camera

and to posing. In the first photograph, Ernestine, (1854-5)

she is very young and either newly married or engaged to Nadar.

Here, she is portrayed as representing the bourgeois values so antithetical

to his bohemian image and lifestyle, yet the camera oddly seems

to take her side. As described by Maria Morris Hambourg, she is

"...Shrewd and cautious, this young woman knows and distrusts

the man with the camera. Attempting to deflect Nadar's effect upon

her, she crosses her arms protectively and with narrowed eyes and

firm jaw resolutely meets his challenge."21 Dressed

in a proper bourgeois dress, the dark, somber material is interrupted

by touches of white on the edges of her sleeves, the white decoration

on her chest and the lace collar framing her face. She sits forward

in her chair, her body and face turned at a slight angle to the

camera, thus disrupting its view. She does not appear to pose, rather

her body appears to brace itself against the camera, an impression

reinforced by the tenseness of her lips and the narrowing of her

eyes. Unlike his other subjects, both male and female, she seems

rather bored, even hostile to the whole process.

Ernestine is portrayed again around 1890. By now,

Ernestine is in weaker health; she has aged and is confined to the

home because of a partial paralysis. In this image, what is striking

is not her physical condition but the beauty and the intense tenderness

that are depicted. The photograph is composed of severe contrasts

between darkness and light, the darkness of the shadows and drapery

played against the softness of her white flowing hair, her pale

aged skin and the white lace blouse that emerges from under the

fabric. She gently holds a bouquet of violets to her lips, a pose

reminiscent of Edouard Manet's painting The Street Singer

of 1862. The focus is on her face, not to convey "moral intelligence"

or dramatic virtues, but to show the intense bond of profound generosity,

trust and love that exists between photographer and subject. While

Nadar's other portraits are characterized by their public nature,

the emphasis on performance, presentation, and theatricality, the

portraits of Ernestine are marked by their simplicity, their subtlety,

their utter lack of artifice. Whereas the other portraits appear

to be caught in a fold, the area between exterior and interior,

between exposure and concealment, the portraits of Ernestine represent

the ultimate interiority.

The three divisions that I have utilized for this

paper are, of course, not exact. Rather, what I wanted to show was

that Nadar's portraiture of women reveals a myriad of attitudes

concerning gender, representation, public and artistic life in mid-to

late-19th century Paris. Much like his earlier photographs of the

mime, Pierrot, who illustrates various emotions and actions, Nadar's

portraits of women illustrate that gender is also a construction,

one which is artificial, neither constant nor consistent, and can

be adopted and imposed. This construction can be read as reflected

in Nadar's portrait photography, as the photographs themselves are

capable of revealing such a construction through the folds, the

betweens, which transcends the subject to create an additional meaning.

As Pollock has written

Indeed, woman is just a sign, a fiction, a confection

of meanings and fantasies. Femininity is not the natural condition

of female persons. It is a historically variable ideological construction

of meanings for a sign W*O*M*A*N which is produced by and for

another social group which derives its identity and imagined superiority

by manufacturing the spectre of this fantastic Other, WOMAN is

both an idol and nothing but a word.22

Sources>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|