|

|

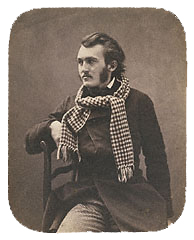

Nadar, Ernestine, 1854-5. Salted

paper print. 24.7 x 17.2 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu.

|

"Nadar" was the name offered by Roland Barthes to his own question as to who was the world's greatest photographers1. The question runs beneath an image he claimed was "one of the loveliest photographs in the world…a supererogatory photograph which contained more that what the technical being of photography can reasonably offer."2 The image is of a white haired woman with soft dark eyes, who through dark velvet folds, lifts a hand obscured by an cream colored eyelet- edged sleeve to gently raise a sprig of violets to her mouth in a gesture so tender, so private, it resembles more the action of a kiss or a breath than a posed portrait. In the text, Barthes identified the photograph as being "of his [Nadar's] mother (or of his wife-no one knows for certain)."3 This ambiguity allowed Barthes to view the image through his own bereavement-the death of his mother-the event that propelled him to search for the ontology of photography, a medium he declared to be structured by loss. That Barthes included a portrait by Nadar in a book on photography is hardly surprising, as Nadar has generally been considered one of the premier portraitists since the time he opened his studio. It is also not surprising that Barthes would chose to project his own longing onto this image, creating a narrative suited to his own purpose as the book is a personal meditation on photography, structured by preferences, or as he claimed "I like / I don't like."4 The photograph that inspired Barthes is markedly different from the images most often associated with Nadar, both in subject, relation and time.5

Celebrated during his lifetime as one of the greatest photographic portraitists, Gaspard Félix Tournachon, known as Nadar received particular renown for his informal photographic and caricature archive of the cultural generated by his photographic portraits of celebrated subjects, players of the mid to late Nineteenth century Paris--"la vie bohéme"-the world in which he portrayed himself as belonging. Despite the acclaim the primary benefit was financial, as the majority of his photographs were cartes des visites commissioned because of his fame. It was through these quotidian photographs that he was able to support himself and fund his other projects.

Nadar stated that the goal of the photographer was to capture the "moral intelligence of your subject - that rapid tact which puts you in communion with your model...and which permits you to give ...the most familiar and favorable resemblance, the intimate resemblance."6 His collodion-on-glass negative photographic portraits contained detailed views; figures seated or standing in three-quarter body shots against neutral backdrops. Like other portrait photographers, Nadar utilized props and costumes, such as drapery, in his photography, yet as opposed to other contemporary portraitists, such as André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri (credited as the inventor of the carte de visite), Nadar's photographs transmited their information through a minimum of sources. Attention was directed to the subjects through the simplicity of the set; instead of employing elaborate backdrops, his subjects were generally seated, facing the camera either frontally or at a three-quarter view. Lighting was both natural and artificial, directed through the use of mirrors to create dramatic shadows, contrasting light tones against dark to enframe his subjects in an aura of light, intended to mirror their personal aura. This luminosity made subjects appear aglow, as if lit from within, an effect amplified by the intense smoothness of the pictorial surface.

While the props were minimal, the surfaces were detailed, drawing attention to the intensity of textural details. The use of props may contain clues to gender roles and identities, roles that may have been emphasized or dramatized for the camera in a type of studio performance. The photographs have an aura of naturalism. The subjects were generally shown in clothing instead of costumes, which had the effect of amplifying this effect. The clothing was chosen over costumes so as to direct attention to the character of the subjects, as constructed through clothing, poses and facial expressions, versus the theatrical distraction of costumes. More than anything else, what has been said to characterize Nadar's portraits was his apparent rapport with his subjects, so as to appear more as collaboration than as a relationship between client and businessman or subject and operator. A central question is how this relationship operates when the client or the subject is a woman.

A portrait is conventionally read as a provider of information-specific details of the subject, mainly physical, are reproduction and represented by the artist. Because photography is an indexical art, the photographic portrait has additional claims to veracity; it is this very claim that leads Barthes to declare that "every photograph is a certificate of presence."7 The portrait photograph typifies what Roland Barthes describes as

...a superimposition here: of reality and of the past. And since this constraint exists only for Photography ...[it is] the very essence, the noeme of Photography...neither Art nor Communication, it is Reference, which is the founding order of Photography. The name of Photography's noeme will therefore be: 'That-has-been,' or again: the Intractable.8

According to Barthes, photography, structured by the "That-has-been," carries within it information, rather than meaning. Nadar's photographic portraits, however, are more than mere conveyers of biographic information, rather, they are essentially "open works," where a multitude of information resides in the betweens - in the shadows, the lighting, the folds of the work such as Umberto Eco describes in The Open Work.9 Yet, in order for the photographic portrait to convey information about the subject, it must first convey information about the world in which the subject operates. As Max Kozloff writes in "Nadar and the Republic of Mind,"

Let's define a portrait as the picture of an individual or group whose character is either described by social, ethnic, and class affiliations, or may, in some measure, be invoked in contrast to them. Sometimes, in the history of the genre, the "personality" of the sitter has gained the upper hand, and, sometimes, his or her status. More often the portrait turns out to be an unpredictable composite image of both.10

In Nadar's portraits of artists, male artists were generally photographed in clothing intended to present bourgeois respectability and modernity. Although the clothing was actually often borrowed from Nadar's studio, it was to have the appearance of being what the subject had worn to the studio. The same straight-forward quality which characterized the portraits was applied to the clothing of the male subject, where nothing was to distract from the physiognomic appearance of the subjects and their "moral intelligence" of which Kozloff writes. However, with his feminine subjects, what was emphasized was less their "moral intelligence" than their physical or corporal presence.

Kozloff writes of Nadar's "republic of mind" stating that

Nadar's republic of mind can't be said to have formed any counterculture within the Second Empire, as if it were simply a question of hip versus straight life-styles. On the contrary, time and again, his artist characters present themselves in the severest terms, the most funereal raiment. In an essay on the Père Lachaise cemetery, Frederick Brown writes: 'Black broadcloth had always been a flag of sobriety in which Europe's bourgeoisie draped itself, not with any illusions that clothing made the man, but, on the contrary, hoping that it would serve to hide him.' It's a sign of their imaginative astuteness that Nadar's sitters often seemed to have used the costume of the bourgeois anonymity to reveal themselves. It became a foil against which they dramatized, for posterity's benefit, a vision of their own unique and sovereign identity. Nadar seems instinctively to have grasped this, in defining just that moment when the face ripens into characteristic self-assertion, toward which the body also swells.11

Kozloff's description is revealing on several counts. First of all, it is telling that Nadar and his bohemian subjects would choose to adopt the bourgeois uniform. Secondly, one would assume that Nadar's photographs specifically, Nadar's photographs of artists, were solely of men. While men do comprise the undeniable vast majority of the photographic portraits, particularly the portraits of artists, female artists, such as Sarah Bernhardt, Georges Sand and Marceline Desbordes-Valmore, were also photographed by Nadar, with Bernhardt and Sand being photographed several times. Although these images are generally included in surveys of Nadar's work, the critical writing about Nadar has neglected to address the questions of gender difference, the effect of gender on the photograph, or to clarify how gender was constructed and portrayed. For it could be argued that Nadar's photographs not only portrayed his subjects physically clothed as the bourgeoisie, but that his works themselves were clothed in bourgeois conventions, expressing conventional ideas of gender and gendered roles. Yet within this bourgeois covering were ruptures and folds, areas of between, overlaps and divisions that revealed schisms and disruptions within that order. It is in this area of gaps and irregularity that his photographs appear to be uniquely suited to operate because it is through operating in these folds that the photographs reveal gender difference of late nineteenth century Paris bohemian and bourgeois culture.12 Through their photographic construction, Nadar's photographs can be read as conveying the idea that gender itself is a construction, something adopted or staged through props and accessories or something put on, like a costume or a painted mask. Gender did play a central role in how the women are presented, if nothing else, because they were denied the option of the black suit of the bourgeoisie, that "flag of sobriety in which Europe's bourgeoisie draped itself," that symbol of modernity of which Baudelaire wrote.

As early as 1856 at the Brussels Photography exhibition of 1856, Nadar was noticed for his 'ravishing portraits of women.'"13 From the beginning of his career as a caricaturist, women artists were represented in Nadar's oeuvre, as evidenced by the celebrated Panthéeon Nadar of 1854 and 1858. In his female photographic portraits, Nadar created a distinction between photographs of women he considered artists-celebrated women such as Marceline Desbordes-Valmore and George Sand-who were generally older and members of "la vie boheème" and whose portraits he exhibited with male artists, and his photographs of young models, actresses, dancers14 that he exhibited with portraits of children and nature studies.15 A third category can be added to the other two-photographs of his wife, Ernestine. Nadar's photographs reveal that he adopted different modes of portraiture for each group, reflecting different concepts of gender construction and socio-economic position, in addition to his own relationship with the subject.

|

|

Nadar, Marceline Desbordes-Valmore,

1854. Salted paper print. 19.6 x 14.9 cm, J.Paul Getty Museum, Malibu.

|

The first group was comprised of portraits of women artists. Artists such as George Sand (1864) and Marceline Desbordes-Valmore (1864) were shown dressed as proper bourgeois ladies, and although they could not adopt the black suited uniform of the male bourgeois, their clothing reflected and conveyed their status and position within this class. The frail frame of Desbordes-Valmore is shown properly attired beneath layers of clothing: patterned scarves cover her head, a stripped bow is tied beneath her chin in a particularly infantalizing gesture, contrasting with the refined, dark color of her dress, whose somberness is interrupted by flouncy white ruffs at her wrists and on her chest. Her black lace covered hands rest on her lap, her arms bent slightly, making them pull away from her body, as she appears to adopts the pose of male artists also shown seated in such a position. Yet within this rather stiff and conventional pose, the position and gesture of her hands becomes particularly interesting. Her right hand rests on a raised leg, obscured by the heavy fabric of her dress. Beneath the intricate black lace glove, bent fingers appear, one flashing a gold band, the other appearing to point to her lap. Her left hand is slightly arched, her first three fingers more visible, almost fully extended, as the index and middle finger separate in the form of scissors, one form appearing to mirror the other. A gap exists between them, an echo of the larger gap between the fingers and the thumb. In this positioning of her hands and their placement on her lap, Desbordes-Valmore appears to interrupt the standard portrait. It is as if her hand appears, perhaps unconsciously, not only to point out difference suppressed by the format, but to point to the area of sexual difference, making a motion of splitting, or separation.16

Generally, the women in this grouping were older and the emphasis was on character and physiognomy-which was to reveal their "moral intelligence." This physiognomic investigation is evidenced by the focus on the lines and forms of Desbordes-Valmore's face, the bags that form under her eyes, the wrinkles that enframe her mouth.17 The saccharine quality of her facial expressions combined with the awkward tilt of her head would inspire Barthes to write that "Marceline Desbordes-Valmore reproduces in her face the slightly stupid virtues of her verses."18

What characterized the second grouping of women, however, was not so much the attention to facial expressions, but the attention to their bodies. Although the body was hidden beneath heavy folds of fabric, such as linen or velvet, or heavy dresses and bonnets, the subject was still read first as a body. Young women, generally of the theater, such as Sarah Bernhardt, or models, were often depicted draped in heavy fabrics that they subtly clutched to their breasts or lay over their shoulder.19 In contrast to the straight, simple lines of the dark suits worn by the men, the bolts of fabric formed deep dramatic folds. Although the drapery provided coverage equal to the bourgeois dress that the older female artists wore, the drapery is a constant reminder of the nude body underneath, the interior precariously covered. This drapery was the opposite of "the costume of the bourgeois anonymity" that the male artists adopted "to reveal themselves," for while the black suits recalled the exterior world, the world of the modern city, the drapery consciously invoked history and interiority: interior settings, such as the studio or even, in the two photographs of Bernhardt, the bedroom, and the interiority of the nude body beneath the clothing. The vacillation between these two conditions-that of interiority and exteriority-can be said to structure these portraits. In addition, it is impossible to view the drapery without thinking of class-the difference that marks the subjects of this grouping as different from the everyday clothing-the bourgeois clothing read as natural-worn by the artists, both male and female.

|

|

Nadar, Gustave Doré

|

Although Nadar also utilized drapery as ornament in his representation of male artists, such as Gustave Doré (1856-58) or Jean Journet (ca. 1855-56), that drapery played a fundamentally different role in the portraits of male subjects. In the portraits of Doré, the elaborately arranged drapery rests on top of the bourgeois black suit, to be read as an individual artistic flourish literally added to the staid, respectable bourgeois uniform. While in the portraits of Journet, the drapery framed his body, like that of a martyr. As Elizabeth Anne McCauley writes

The use of a velvet mantle flowing around a nude torso, adding mass and visual richness, was less a derivation of high fashion than a borrowing of the baroque symbolism of genius and power. By removing the figure from contemporary life, this framing device focused attention on the face and encouraged comparisons with Bernini's bust of Louis XIV or a Roman portrait bust, in which a specific likeness contrasts with generalized, dynamic drapery....20

At least three of Nadar's photographs of Bernhardt produced between 1864 and 1865 showed Bernhardt covered in heavy fabric, leaning on a pillar in poses and compositions so similar that one could mistake several photographs for multiple exposures shot at the same session. On closer inspection, differences emerge: the color of the drapery, the position of Bernhardt's form, her slightly differing facial expressions and the lighting of the scene. Nadar's photographs of Bernhardt were markedly different, distinguishing this series from both Bernhadt's representation in the work of other photographers and Nadar's other subjects. In the photographs, Bernhardt was shown immersed in voluminous drapery in Nadar's standard three-quarter body view. She leans on a truncated column, dramatically draped in either light or very dark colored drapery, which forms thick folds and creases around her body. The loose, undulating form of the drapery is echoed in her free flowing hair that curls around her face, highlighting her facial features, the focus of the work. The lighting, which produces gentle gradations of shadow and light and the smooth, glossy surface creates an overall effect of luminosity and polish and allows fine details-such as the texture of the cloth, the tasseled details at the borders, the metal of her earrings and the gloss on her lips- to be revealed. The goal of the photograph was not only to portray her dramatic, daring spirit, but to show that this artistic soul can be most fully and accurately portrayed, indeed can only be portrayed, through a fellow artist, Nadar.

|

|

Nadar, Sarah Bernhardt, ca. 1864.

Modern print from a glass negative. 30 x 24 cm. Caisse Nationale

des Monuments Historiques et des Sites, Paris.

|

The photographs of Sarah Bernhardt are characterized by their dramatic use of drapery. Although drapery was used with other women and some men, it is at its most voluminous, most conspicuous in the portraits of Bernhardt. It is also integral to the meaning of the photographs as it is in the multitude of voluminous folds that the meaning of the works reside. The works can be said to be like the folds, to be between layers in which questions of gender, social class, art reside. The folds encompass layers of fabric, between which fall deep shadows, paralleling the world of betweens in which Nadar and his milieu operated. The folds that were most prominent in Bernhardt's drapery, significant as the fold can be associated not only with her portrait, but with Bernhardt, who, as a woman, transgressed the typical gendered role for women and operated in a zone of the fold, between artist and muse, between bourgeois and bohemian, between the male artists and that of the sexualized and/or maternal body. Her portrayal, with the thick, almost sculptural folds of fabric, the classical pose leaning on a columned pillar consciously recall poses associated with the history of art, although Nadar himself was a firm proponent of modernity, deriding painters such as Jean Auguste Dominque Ingres for the stale and sterile quality of their work with its emphasis on line and classical composition.

Yet the drapery and props cast Bernhardt more as a muse or model than as a fellow artist. Compared with Gustave Courbet's Studio of A Painter: A Real Allegory Summarizing My Seven Years of Life as an Artist, (1854-5), Bernhardt occupies a position similar to the female model located in the center of the painting. The woman in the painting stands behind the artist (Courbet), a figure of silent support with a look of dreamy intent while watching the artist paint a landscape. She is nude except for a white cloth she holds to her body, which does not so much cover her as emphasize her nudity. Her nudity is further reinforced by the crumpled pink and white pile formed by her dress that lies on the floor in front of her. The woman's role in the work is ambiguous - she may be a muse, or divine inspiration, or a model for another work. Like the landscape he is painting, the woman represents a standard artistic convention-the nude-that evokes high art. She also can be read as symbolizing nature, her purity and innocence emphasized by her association with the boy, the dog and the landscape being painted. Her "naturalism" is reinforced by her nudity - she does not adopt the clothing (or artifice) of the bourgeoisie or the Parisian artists gathered around the back of the canvas, rather, she stands, in a "pure" state, looking over the artist's shoulder in support of his genius and the culture he symbolizes.

|

|

Maria, 1856-9 .

|

To say that Nadar presents Bernhardt as representing "Nature," would be incorrect, but it is important to note how different her representation is from the male artists and how much closer the resemblance is to Courbet's nude model or 'muse,' and Nadar's portraits of the model Maria. Nadar's portraits of Bernhardt also differ significantly from how she was portrayed by other photographers. Comparing an 1877 woodbury portrait of Bernhardt by Emile Tourtin with Nadar’s images, one notices in both series a concerted focus on material, yet the elaborate volumes of Nadar’s drapery are replaced in Tourtin by elegant lace, pearls and jewels. Bernhardt's elaborately flounced white dress, composed of layers of ruffles, laces, pleats and folds and buttons, thick ropes of pearls dangling from her arms, her ears and around her neck over a rhinestone choker, and the large white flower in her hair portray not just a different image, but a different type of person than in Nadar's images. In Nadar's photographs, Bernhardt, though shaded, appears more in focus and physically closer to the viewer by appearing to lean into the camera, while in Tourtin's image she appears hazy and out of focus, as if weighed down by the layers of artifice that connote a specific class. In the Tourtin, Bernhardt lacks a connection with the viewer (and by association with the photographer), rather she turns her head at a three-quarter angle, hiding half of her face and focusing her gaze to the side, out of the range of the camera. In such a work, what one sees is more an official portrait than a collaboration, for in Tourtin's image, she is Sarah Bernhardt, the celebrated actress, more a personality, a successful performer off-duty than an artist. In such a work, the emphasis is on the external, whereas Nadar attempts to strip her image of artifice in an attempt to reach the internal, the core, of her as an artist, and as a woman, by association, the unknowable "other."

The dialogue between interiority and exteriority as projected onto the female body culminates with the two photographs of Maria (1856-9) and Paul Nadar and his Nurse, 1856. Little is known about the model from Antilles named Maria. In the first photograph, Maria is presented with her body and face turned away from the camera, a large portion of her face hidden in shadow. Her hands are tightly clasped around the drapery to form a closure, while her arms are crossed against her front as a double barrier, dramatic, opalescent light which shines on her arms creating a visual distraction, a diagonal that not only blocks the gaze from her front but leads the eye to her shoulder and the backdrop. In contrast, the other photograph is more about exposure. Strongly lit, Maria faces forward, her arm rests on the back of the chair and her hand is on her cheek, drawing attention to her face which is turned at a slight angle and her gaze off-camera. The drapery falls open, exposing her breasts, which are only slightly lower than the center of the photograph. The two works emphasize the effects of uncovering and revealing, and the fine line that exists between the nude body swathed in drapery and the body exposed when the drapery falls away.

The body exposed, or the interior rupturing the façade of the exterior also can be seen in the photograph of Nadar's son, Paul, being fed by his wet nurse (Paul Nadar and his Nurse, 1856). The bodies of the nurse and the baby are almost entirely covered by cloth-white bonnets cover their heads and are tied securely below their chins, the baby is covered in layers of fabrics and blankets held by the nurse who wears a black lace shawl overtop of her black dress which primly extends to the her neck in a white lace collar. Yet despite the excessive covering, the body emerges in the form of the woman's naked breast, firmly clenched by her darker skinned hands that she offers to the child for a feeding. This action creates an opening, a disruption in the layers of fabric, and the emergence of what is normally hidden and contained, representative of the interior and the private, becomes exposed, public, and viewed. This exposure also reveals what ultimately codes her, not only in terms of gender and sexuality, but also racially and socio-economically-it reveals her position in Nadar's world.

The last category of female portraiture is reserved for only one person-Nadar's wife, Ernestine. In these works, the subject cannot be reduced to distinctions of artist, client, or model, as she transcends such categories. Instead,her portraits are characterized by intense intimacy between the subject and the photographer. Ernestine does not utilize studio props or costumes, in fact, she appears to have an active resistance to the camera and to posing. In the first photograph, Ernestine, (1854-5) she is very young and either newly married or engaged to Nadar. Here, she is portrayed as representing the bourgeois values so antithetical to his bohemian image and lifestyle, yet the camera oddly seems to take her side. As described by Maria Morris Hambourg, she is "...Shrewd and cautious, this young woman knows and distrusts the man with the camera. Attempting to deflect Nadar's effect upon her, she crosses her arms protectively and with narrowed eyes and firm jaw resolutely meets his challenge."21 Dressed in a proper bourgeois dress, the dark, somber material is interrupted by touches of white on the edges of her sleeves, the white decoration on her chest and the lace collar framing her face. She sits forward in her chair, her body and face turned at a slight angle to the camera, thus disrupting its view. She does not appear to pose, rather her body appears to brace itself against the camera, an impression reinforced by the tenseness of her lips and the narrowing of her eyes. Unlike his other subjects, both male and female, she seems rather bored, even hostile to the whole process.

Ernestine is portrayed again around 1890. By now, Ernestine is in weaker health; she has aged and is confined to the home because of a partial paralysis. In this image, what is striking is not her physical condition but the beauty and the intense tenderness that are depicted. The photograph is composed of severe contrasts between darkness and light, the darkness of the shadows and drapery played against the softness of her white flowing hair, her pale aged skin and the white lace blouse that emerges from under the fabric. She gently holds a bouquet of violets to her lips, a pose reminiscent of Edouard Manet's painting The Street Singer of 1862. The focus is on her face, not to convey "moral intelligence" or dramatic virtues, but to show the intense bond of profound generosity, trust and love that exists between photographer and subject. While Nadar's other portraits are characterized by their public nature, the emphasis on performance, presentation, and theatricality, the portraits of Ernestine are marked by their simplicity, their subtlety, their utter lack of artifice. Whereas the other portraits appear to be caught in a fold, the area between exterior and interior, between exposure and concealment, the portraits of Ernestine represent the ultimate interiority.

The three divisions that I have utilized for this paper are, of course, not exact. Rather, what I wanted to show was that Nadar's portraiture of women reveals a myriad of attitudes concerning gender, representation, public and artistic life in mid-to late-19th century Paris. Much like his earlier photographs of the mime, Pierrot, who illustrates various emotions and actions, Nadar's portraits of women illustrate that gender is also a construction, one which is artificial, neither constant nor consistent, and can be adopted and imposed. This construction can be read as reflected in Nadar's portrait photography, as the photographs themselves are capable of revealing such a construction through the folds, the betweens, which transcends the subject to create an additional meaning. As Pollock has written

Indeed, woman is just a sign, a fiction, a confection of meanings and fantasies. Femininity is not the natural condition of female persons. It is a historically variable ideological construction of meanings for a sign W*O*M*A*N which is produced by and for another social group which derives its identity and imagined superiority by manufacturing the spectre of this fantastic Other, WOMAN is both an idol and nothing but a word.22