|

|||||||||||

|

Luke Smalley, “Gymnasium,” Wessel + O’Connor Gallery,

242 W. 26th St., New York, October 12-November 25, 2001

Luke Smalley is a Pennsylvania-based photographer whose subject

in his first solo exhibition and book are male high school athletes.

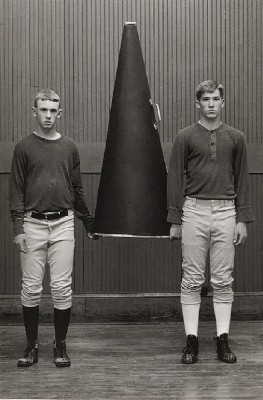

Smalley’s work is not the stuff of celebratory small town photojournalism

but rather an elaborately crafted and posed body of photos whose

participants, though real athletes (Smalley found them in various

Pennsylvania and Ohio high schools), act out a series of scenarios

using antique athletic equipment, much of it fashioned by Smalley

himself. The premise of the project is outlined in an uncredited

text at the beginning of the book version of Gymnasium, which extols

the idealized athletic boy at the expense of angst-ridden, academics-obsessed

adolescents who spend far too many hours brooding in their rooms.

“It is the boys who have snap and vim and energy, who have

a plentiful supply of ‘ginger,’” Smalley quotes (or

writes himself, in which case his text is a masterful recreation

of what might be called the Boy Scout Handbook aesthetic), “that

accomplish results of importance...The boy who wants to be strong

and rugged, who wishes to grow up into a superb, manly man, and

who uses his surplus energies and wholesome games and in a temperate

amount of study, will avoid without the slightest effort all that

is evil.”1

There are, of course, various traditions which can be invoked as

a way of framing Smalley’s work. The artifice on display here,

that of consciously relocating the subject in time and space, is

deeply embedded in photographic history. Unlikely as it may seem,

the true progenitors of Smalley’s work are the constructed

tableaux of nineteenth century photographers like Oscar Rejlander

and Henry Peach Robinson, perhaps even the allegorical portraits

Julia Margaret Cameron made of friends and family in the 1860s and

70s.2 One can also cite the more contemporary works of

Philip-Lorca DiCorcia and Cindy Sherman, two photographers (among

many) who take as the subject of their photography questions of

constructed identity and the ambiguous nature of photographic “truth.”3

More obvious even to the casual observer is Smalley’s debt

to a longstanding and diverse tradition of homoerotic subject matter

in photography. In this sense, the photos in Gymnasium are derived

from Wilhelm von Gloeden and Fred Holland Day’s early twentieth

century work and updated by way of Bruce Weber, though divested

of nudity and any overt sensuality along the way.4 The

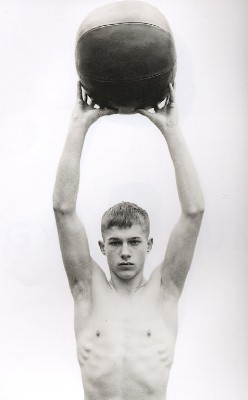

youngest subject in Gymnasium, a buzz-cut boy wearing black trunks

and nothing else, could in fact have stepped from the frames of

“Broken Noses,” Weber’s 1987 cinematic gaze at a

boys’ boxing club in the Pacific Northwest. For all Weber’s

contrivance, though, for all the hair gel and moody lighting and

naked romping with dogs and each other, he allows his subjects a

naturalism that Smalley’s more narrowly defined athletes do

not have. We know nothing about them outside of their fabricated

contexts; they are unnamed, the photos themselves untitled, and

the boys have been stripped of everything but their bodies, their

poses, their unmediated gaze at the lens.

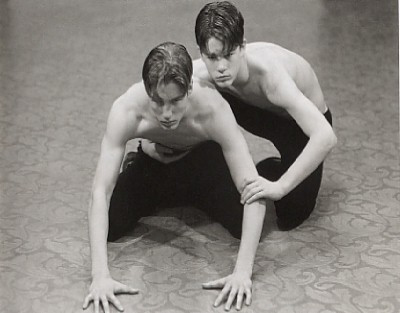

Gymnasium is boy after boy, crouching, lifting, hurling, running,

rowing, lunging, in pairs, in trios, alone. These boys are physical

paradigms all, embodiments of body, for the most part unsmiling,

willing participants in the recording of body-glory. There are no

depictions of athletes of color and a tacit nod to contemporary

gay aesthetics of beauty (no body hair to be seen on Smalley’s

athletes, no bad complexions, no one fat or misshapen or conventionally

ugly). Smalley seems most interested in documenting a nostalgic

history of the primal urge boys have to play games, to test themselves,

to measure athletic prowess, to achieve athletic success. There

isn’t much about the thrill of victory here, though the emotions

of defeat are also all but absent. In one photo, a boy sits alone

on a throne-like chair, wearing white shorts, a pair of antique

cleats and a banner across his perfect bare chest that proclaims

“FIRST.” The boy’s face is blank; he sits like a

prince unimpressed or even unaware of his kingdom. In another photo,

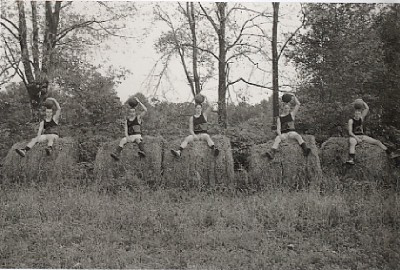

a quintet of boys sit on enormous rolled hay bales, balancing basketballs

on their heads with their left hands, their right hands dangling

between splayed legs. They do this not because they reenact some

forgotten ritual of gymnasium culture but because Smalley thought

this would make an interesting composition. (In a companion photo,

the same quintet stands on the hay bales and now balances the balls

on their heads with their right hands.) The expressions on the boys’

faces, though hard to read from a distance, appear as uninflected

as the seated boy with his banner. They are plainly not thinking

about artifice and the construction of nostalgia and the homoerotic

gaze; they are doing what Smalley told them to do, and that seems

enough.

The unasked question in Gymnasium is not necessarily one about the artist’s intention (which seems clear enough) or about the propriety of studying and documenting adolescent sexuality (however peripheral this is in Smalley’s photos). It is instead a question about fabricated identity and possibly fabricated desire. Smalley’s work taps into the twin grails of contemporary advertising culture, youth and beauty (and the longing for both). He aestheticizes his subjects, strips them of sweat, grime, blood and the smells of locker room and playing field, strips them as well of the pervasive sports-based and gym-class cruelty which presumably dominates the adolescent memories of most non-athletes. Smalley’s athletes are purified, in other words, in form but also in sensibility. This further distances us (and them) from the complicated contemporary reality of sports, from the troubling issues of adolescent sexual allure. These photos, because of the obvious inaccessibility of their subjects, create a kind of illicit (and unfulfillable) longing, an impossible desire which is paradoxically permitted only in the act of looking at the photos themselves. Are any of his high school athletes gay? Are any of them aware that the majority of the viewing audience for Smalley’s photos are likely to be gay men? Would they care if they knew? In the orderly and nostalgic world of Gymnasium, none of the answers seem to matter.

|

|||||||||||