| |

|

|

|

For Ben Shahn, the years 1929-31 were a pivotal time of stylistic

and thematic changes in which photography played a crucial role.

It has been established that the photographer Walker Evans was responsible

for introducing Shahn to photography.1 However, the “profound

difference”2 embedded in the two artists’ conception of

photography has rarely been discussed. Shahn and Evans never compromised

their artistic visions regarding the compatibility of art and ideology;

Shahn consistently attempted to convey his reformative social visions

through his pictorial narratives, whereas, in treating a variety

of themes ranging from the documentary to formal abstraction, Evans

maintained neutral and detached attitudes toward the subject matter

of his photographs. An analysis of Shahn’s two portraits of

Evans and The Dreyfus Affair, all done in 1930, and some of Evans’s

photographs taken and published in 1928-30 may provide a clue to

characterize their different approaches to art.

Shahn, a Russian-Jewish immigrant whose father was a woodcarver

and active socialist, became aware of the corruption interwoven

into the fabric of society and sympathetic toward the victims of

social injustice. In adapting to his new country, Shahn experienced

new, yet no doubt familiar, forms of anti-Semitism, “more subtle

than those enforced by the Russian Czar, but no less effective in

maintaining a social hierarchy.”3 Although he had been making

a living as a lithographer since his late teens, Shahn prepared

to be a painter.4

During his trips to Europe in the 1920s,5 Shahn, while experimenting

with the Post-Impressionst and Fauvist styles of Cézanne,

Matisse, Rouault, and Dufy, was also exposed to George Grosz’s

critical visual narrative. In 1925, four years prior to his encounter

with Evans, Shahn saw in Vienna a copy of Ecce Homo (1922) by Grosz.

In retrospect, Shahn revealed that he was deeply moved by the drawing:

“I almost dropped dead in excitement over it.”6 He bought

a copy. Within the drawings, an acid sarcasm towards bourgeois indulgence

in sexual pleasure is conveyed through lively charged, razor-sharp

lines. Its revealing content and narrative brevity might have provided

Shahn with an excellent model. Shahn, however, was never drawn to

the erotic themes that the German artist often depicted to represent

bourgeois moral perversity. Through Grosz, who began his career

as a graphic artist and whom Shahn admired as “the greatest

draftsman of this century,”7 Shahn perhaps confirmed his desire

to develop from a draftsman to an artist revealing social reality.

After Grosz came to New York, Shahn would visit him in 1933 and

1935 and be given two drawings.8 Shahn enthusiastically groped for

an appropriate style to express narrative messages, yet he still

had not found his own style by the time he met Evans.

Unlike Shahn, Evans was critical of the cultural pretensions of

American bourgeois society. Despite his sheltered middle-class background,

he rejected the security of bourgeois life. Even his attempt to

become a photographer seemed to be “a willful act of protest

against a polite society in which young men did what was expected

of them.”9 In his biography, Evans recalled “My poor father,

for example... decided that all I wanted to do was to be naughty

and get hold of girls through photography, that kind of thing. He

had no idea I was serious about it. And respectable, educated people

didn’t. That was a world you wouldn’t go into. Of course,

that made it more interesting for me, the fact that it was perverse.”10

In 1927 Evans returned to New York after spending one year in Paris

and decided to become a photographer. Like “a conventional,

if well-groomed, bohemian,”11 Evans toured the city taking

pictures while supporting himself through a series of temporary

jobs.

|

|

|

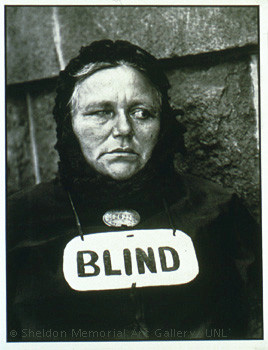

In the late 1920s, Evans was assimilated to a kind

of objective realism. The writing of Flaubert that he had avidly

read in Paris and the early photographs of Paul Strand among others

inspired him in that direction. Paul Strand’s Blind Woman,

1916,(fig. 2) was a powerful source.12 Evans was drawn to the photographer’s

frontal representation of the old blind woman, which minimized the

traces of the artist’s emotional response to his subject. Ultimately,

realistic content and objective authorship formed two axes of Evans’s

photographic world. In an interview Evans stated: “I think

I incorporated Flaubert’s method almost unconsciously, but

anyway I used it in two ways; both his realism, or naturalism, and

his objectivity of treatment. The non-appearance of the author.

The non-subjectivity. That is literally applicable to the way I

want to use a camera and do.”13

Within this frame of logic, Evans had access to

realistic themes of documentary photography that had specific references

to American life at a specific moment and to modernism’s rational

and reductive formal structure. Throughout his career, Evans’s

pictures incorporate a range of diverse themes, from the lives of

ordinary people to the structural abstraction.

Evans’s New York photographs of 1928 and 1929 demonstrate his

double interest in formal abstraction and the documentation of American

life. Within balanced compositions and formidable contrasts of black

and white, his pictures portray anonymous pedestrians, clerks working

in shops, workers resting on the street. One of his first published

photographs, printed in Creative Art of December 1930, shows a busy

lunch counter scene in the city.

These various themes represent Evans’s tendency

toward a neutral observation of the lives of the city’s denizens.

Another group of Evans’s photographs of this time demonstrates

his photographic exploration of geometric composition. These pictures

focus on architectural patterns and the spatial relationships of

modern buildings. A photograph taken in 1928 or 1929 published in

Architectural Record in 1930 even recalls Charles Sheeler’s

Criss-Crossed Conveyors, Ford River Rouge Plant, 1927 in its diagonally

crossing composition seen from below. The Precisionist’s articulation

of the precise structures underlying the machine and the architecture

may have reinforced Evans’s photographic experiments with reductive

abstraction.

|

|

|

Shahn and Evans were intellectually attracted to

each other when they first met in September 1929. Just after his

return from Europe, Shahn saw Evans at the home of a mutual friend,

Dr. Iago Geldston. At Shahn’s insistence,14 Evans moved into

the ground-floor studio of Shahn’s apartment at 21 Bethune

Street in Greenwich Village. The Shahns lived on the two floors

directly above Evans’s studio and Shahn painted in his own

living room.15 As Judith Shahn, the artist’s daughter, recalled,

“Evans was like a member of the family; he was frequently invited

upstairs for supper in the kitchen.”16 “For Evans,”

observed his biographer Berlinda Rathbone, “no one could have

been a better ally at that moment than the energetic and canny Ben

Shahn.”17 According to Bernarda Bryson Shahn, who met Shahn

in 1933 and two years later became his wife, “Both artists

initially enjoyed each other’s witty, free-minded personalities.”18

Central to their free-mindedness was a shared subversive attitude

regarding established bourgeois society. While Evans’s concern

was geared more toward bourgeois cultural prejudices, Shahn’s

was toward art’s positive function as ideological reformation.

Shahn had been interested in photography before he met Evans and

began taking pictures in the early 1930s.19 Amongst Strand’s

early “straight” photographs that register minute details

and the subtle tonal ranges of objects, his photographs of pedestrians

especially impressed Shahn. “Learning from Strand, Shahn often

turned his attention to the individual in the urban setting,”

observed art historian Susan Edwards.20 Both Shahn and Evans welcomed

straight photographs to the extent that they later discussed collaborating

on a photography book in which they would oppose both the artificiality

of Pictorialist subjects such as female nude 21 and the blurry mechanism

of the soft-focus Pictorialism. They rejected romantic subject matter

and idealizing techniques, but Shahn was further drawn to the humanistic

content of Strand’s early photograph and its critical potential

to reveal an underside of society.

In 1930, while working on the subject of The Dreyfus Affair,22 Shahn

painted two portraits of Evans. The portraits show expressive styles

of Shahn’s pre-photographic period. Shahn’s painterly

representations of the photographer suggest the complex nature of

the two artists’ acquaintanceship; for Shahn, a portrait meant

the painter’s critical observation of the sitter, rather than

a flattering resemblance.23

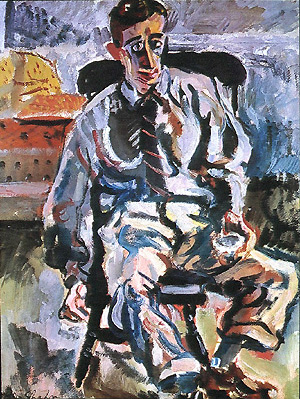

On the simplest level, the two portraits show Evans sitting on a

chair. One is painted in oil(fig. 1), the other in watercolor .

The canvas of the oil portrait is thickly painted with agitated

brushstrokes in bright colors. Evans, in a dress shirt, is arrested

in an action while sitting on a wooden chair with his legs spread

and holding a camera lens, an evident marker of his profession.

The broad contouring used in some parts, the freedom of brushstrokes,

and the sporadically applied blue, orange, and dark brown recall

Georges Rouault’s early watercolors to which the French painter

often added pastel for heavy texture. In comparison, Shahn shows

clearer spatial order and emphasizes the fluidity of brushstrokes,

creating a more overall elegance than Rouault.

Shahn divided the watercolor portrait into three transparent color-patches:

blue, covering the area of the battered wicker chair and the upper

body of Evans; white, Evans’s trousers; and a light wash in

pale yellow of the surrounding area. While making each color-patch

into a concrete shape, the calligraphic and elliptical contours

and linear details added later not only give the patches vibrating

rhythms, but also enliven the freshness of each color without reducing

the color to a function of simple representation. Within this overall

scheme, the torso of Evans is barely distinguished by the few flowing

lines from the chair in which he is slouching. His shoulders are

hunched and his hands are digging into his pockets. The transparent

colors and calligraphic linear details are associated with Raoul

Dufy’s painting; unlike the Fauve, who depicted figures in

a more stylized manner, Shahn emphasizes the individuality of the

sitter.

Within both portraits, Evans’s likeness is captured through

free yet concise details. Evans’s sensitive or “squeamish”24

personality is suggested through his physiognomy, unique pose, and

neat costume. Hardly the idealized type of portraiture, the activated

brushstroke and bodily exaggeration evoke a sense of intense psychological

and intellectual exchanges between the painter and the sitter. Neither

portrait contains any obvious iconographic sign that proves Shahn’s

critical apprehension of the photographer, but Shahn’s expressive

form and color connote the essential difference embedded in their

art; at this time Shahn chose to reject formalist-modernism in favor

of a more realistic representation conveying concrete narrative

contents. Shahn, who acknowledged in 1929 that “the French

school is not for me,”25 baptized Evans with the painterly

style of the French school, colorfully characterized the detached

nature of Evans’s modernist aestheticism, and covertly differentiated

the photographer from himself.

|

|

|

During the summer of 1930, Shahn and Evans had a

two-day joint exhibition in the barn of a Portuguese neighbor on

Cape Cod, where they spent the summer. Shahn hung The Dreyfus Affair

(fig. 4), a series of works created specially for the exhibition

and Evans exhibited his photographs of the neighbors, the Deluze

family.

The Alfred Dreyfus Affair, the case of the Jewish officer in the

French Army falsely accused of treason, shook France in the 1890s.

Participating in political protests in Paris over the more recent

Sacco and Vanzetti case in America (the trial of two anarchist Italian

immigrants convicted of murder on flimsy evidence), Shahn perceived

the Dreyfus case to be a similar conspiracy of the social system

against ethnic minorities and the working class.

To create The Dreyfus Affair, Shahn first used published photographic

images as models.26 From photographs in the relevant books, old

magazines and news articles, he painted the major players in the

Dreyfus trial. Fine details are added to broad washes of facial

area and clothing to characterize the faces and costume decorations.

The backgrounds are left empty or covered with a pale wash. Each

portrait has the carefully lettered name in different scripts, the

hard edges of which are in sharp contrast with the washed areas

of a figure. Despite the quick application of washes, each portrait

shows proper bodily proportion, clear features, and additive details

drawn with exactness. The Dreyfus Affair demonstrates Shahn’s

magnificent graphic skill attained through lithographic training.

The shaded areas of the faces suggest volume and space, yet most

of the portraits are painted flat. The optical flatness is reinforced

by the impersonal arrangement of the letters. The shallow space

and fine details are possibly transferred from the photograph, in

which abrupt changes of light and shade often cause similar flat

effects. The overall transparent colors of The Dreyfus Affair, however,

do not effectively emphasize the seriousness of the historical trial.

This lightness would disappear with the emphatic patterns--the darker

tonalities, nervously broken lines, and an undercurrent of distortion--of

The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti that he began to paint the following

year.

One of the Deluze photographs exemplifies Evans’s photographic

treatment of the subject. The interior scene shows a prickly cactus

plant set against the framed family photographs, a souvenir American

flag, and a vase of dried flowers. Through the straight photographic

technique, both photographs keep the same degree of descriptive

exactitude for the objects from the foreground to the background.

Particularly in the photograph of the cactus plant within an airless

space, the equally distinctive contours and the scattered dark areas,

in strong contrast to the white wall, push the photographed objects

all-over to the picture plane. This reductive formal process of

the photographic still life helps objectify its content, the commonplace

American domestic space.

Taken slightly later, however, Hudson Street Boarding House Detail

(1931-33) shows an interior scene of a bedroom. In this bedroom

picture, the decorative quality is retained by the curvilinear patterns

of the wrought-iron bed and the black and white contrast of the

bedspread and surrounding areas. However, the shabby interior--the

rough wall, the drooped curtains, and the sunken mattress—reveals

an economically dire situation. Here, the decorativeness of this

photograph collides with its unavoidable suggestion of a specific

relation to the outside world; this collision of formal abstraction

and social implication makes possible multiple ways of appreciation

and interpretation of the work. In this way, Evans refused to assign

a predefined meaning to his photography.

Evans’s emphasis upon the absence of the author was another

unacceptable point to Shahn, who was conscious of the artist’s

social contribution through critical interpretation and active involvement.

In response to Shahn’s arguments about the ideological function

of art, Evans said: “I wouldn’t let him touch or influence

me. If he said I took Depression pictures of human havoc, and I

would say that was what I was doing, I would walk out and wouldn’t

let him discuss this.”27 In a detached manner, Evans frequently

documented subjects that contained specific social situations throughout

his career, particularly in 1935 and 1936 when he was hired by the

Resettlement Administration/Farm Security Administration.

|

|

|

Despite the irreconcilable difference in their artistic

visions, Shahn would incorporate the less formalized type of Evans’s

early documentary photographs into his art. These photographs often

fail to embody objective approach, as Evans himself recalled: “In

1928, ‘29 and ‘30 I was apt to do something I now consider

romantic and would reject.”28 The oblique angle of these photographic

studies of people creates a perspectival recession that distracts

the viewer from direct visual confrontation with the photographic

subject. In the late Thirties, Shahn would use a similar diagonal

composition in his own photographs of ordinary people used for his

“personal realist” work.29 For instance, the subject of

workers resting on the street, which Evans photographed in 1928

or 1929 (fig. 5), is echoed in Shahn’s photograph, Sunday,

1937, and the same subject is again transformed into the painting,

W.P.A. Sunday, 1939.

By the early 1930s, Shahn must have fully appreciated Evans’s

ambivalent attitudes toward the variety of photographic themes.

Despite the evident differences in their early careers, Evans’s

extensive experimentation with photography offered an immediate

and ample environment in which Shahn became aware of the usefulness

of photography for the representation of realistic visual drama.

Whereas Evans attempted to privilege photography as a fine-art medium

capable of embodying diverse formal and thematic tendencies, Shahn

integrated photographic images and details into his painting to

convey historically specific and ideologically critical narratives.

The portraits of Evans painted by Shahn at the moment of their stylistic

breakthrough suggest intimate, intense and critical dialogues between

the two young artists.

Sources>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|