|

For Ben Shahn, the years 1929-31 were a pivotal time of stylistic and

thematic changes in which photography played a crucial role. It has been

established that the photographer Walker Evans was responsible for introducing

Shahn to photography.1 However, the “profound difference”2 embedded

in the two artists’ conception of photography has rarely been discussed.

Shahn and Evans never compromised their artistic visions regarding the

compatibility of art and ideology; Shahn consistently attempted to convey

his reformative social visions through his pictorial narratives, whereas,

in treating a variety of themes ranging from the documentary to formal

abstraction, Evans maintained neutral and detached attitudes toward the

subject matter of his photographs. An analysis of Shahn’s two portraits

of Evans and The Dreyfus Affair, all done in 1930, and some of Evans’s

photographs taken and published in 1928-30 may provide a clue to characterize

their different approaches to art.

Shahn, a Russian-Jewish immigrant whose father was a woodcarver and active

socialist, became aware of the corruption interwoven into the fabric of

society and sympathetic toward the victims of social injustice. In adapting

to his new country, Shahn experienced new, yet no doubt familiar, forms

of anti-Semitism, “more subtle than those enforced by the Russian

Czar, but no less effective in maintaining a social hierarchy.”3

Although he had been making a living as a lithographer since his late

teens, Shahn prepared to be a painter.4

During his trips to Europe in the 1920s,5 Shahn, while experimenting with

the Post-Impressionst and Fauvist styles of Cézanne, Matisse, Rouault,

and Dufy, was also exposed to George Grosz’s critical visual narrative.

In 1925, four years prior to his encounter with Evans, Shahn saw in Vienna

a copy of Ecce Homo (1922) by Grosz. In retrospect, Shahn revealed that

he was deeply moved by the drawing: “I almost dropped dead in excitement

over it.”6 He bought a copy. Within the drawings, an acid sarcasm

towards bourgeois indulgence in sexual pleasure is conveyed through lively

charged, razor-sharp lines. Its revealing content and narrative brevity

might have provided Shahn with an excellent model. Shahn, however, was

never drawn to the erotic themes that the German artist often depicted

to represent bourgeois moral perversity. Through Grosz, who began his

career as a graphic artist and whom Shahn admired as “the greatest

draftsman of this century,”7 Shahn perhaps confirmed his desire to

develop from a draftsman to an artist revealing social reality. After

Grosz came to New York, Shahn would visit him in 1933 and 1935 and be

given two drawings.8 Shahn enthusiastically groped for an appropriate

style to express narrative messages, yet he still had not found his own

style by the time he met Evans.

Unlike Shahn, Evans was critical of the cultural pretensions of American

bourgeois society. Despite his sheltered middle-class background, he rejected

the security of bourgeois life. Even his attempt to become a photographer

seemed to be “a willful act of protest against a polite society in

which young men did what was expected of them.”9 In his biography,

Evans recalled “My poor father, for example... decided that all I

wanted to do was to be naughty and get hold of girls through photography,

that kind of thing. He had no idea I was serious about it. And respectable,

educated people didn’t. That was a world you wouldn’t go into.

Of course, that made it more interesting for me, the fact that it was

perverse.”10 In 1927 Evans returned to New York after spending one

year in Paris and decided to become a photographer. Like “a conventional,

if well-groomed, bohemian,”11 Evans toured the city taking pictures

while supporting himself through a series of temporary jobs.

|

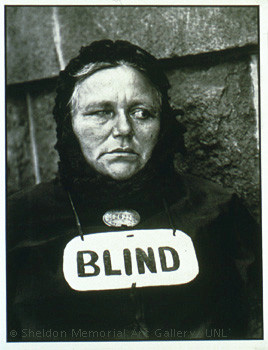

In the late 1920s, Evans was assimilated to a kind of

objective realism. The writing of Flaubert that he had avidly read in

Paris and the early photographs of Paul Strand among others inspired him

in that direction. Paul Strand’s Blind Woman, 1916,(fig. 2) was a

powerful source.12 Evans was drawn to the photographer’s frontal

representation of the old blind woman, which minimized the traces of the

artist’s emotional response to his subject. Ultimately, realistic

content and objective authorship formed two axes of Evans’s photographic

world. In an interview Evans stated: “I think I incorporated Flaubert’s

method almost unconsciously, but anyway I used it in two ways; both his

realism, or naturalism, and his objectivity of treatment. The non-appearance

of the author. The non-subjectivity. That is literally applicable to the

way I want to use a camera and do.”13

Within this frame of logic, Evans had access to realistic

themes of documentary photography that had specific references to American

life at a specific moment and to modernism’s rational and reductive

formal structure. Throughout his career, Evans’s pictures incorporate

a range of diverse themes, from the lives of ordinary people to the structural

abstraction.

Evans’s New York photographs of 1928 and 1929 demonstrate his double

interest in formal abstraction and the documentation of American life.

Within balanced compositions and formidable contrasts of black and white,

his pictures portray anonymous pedestrians, clerks working in shops, workers

resting on the street. One of his first published photographs, printed

in Creative Art of December 1930, shows a busy lunch counter scene in

the city.

These various themes represent Evans’s tendency toward

a neutral observation of the lives of the city’s denizens. Another

group of Evans’s photographs of this time demonstrates his photographic

exploration of geometric composition. These pictures focus on architectural

patterns and the spatial relationships of modern buildings. A photograph

taken in 1928 or 1929 published in Architectural Record in 1930 even recalls

Charles Sheeler’s Criss-Crossed Conveyors, Ford River Rouge Plant,

1927 in its diagonally crossing composition seen from below. The Precisionist’s

articulation of the precise structures underlying the machine and the

architecture may have reinforced Evans’s photographic experiments

with reductive abstraction.

|

Shahn and Evans were intellectually attracted to each

other when they first met in September 1929. Just after his return from

Europe, Shahn saw Evans at the home of a mutual friend, Dr. Iago Geldston.

At Shahn’s insistence,14 Evans moved into the ground-floor studio

of Shahn’s apartment at 21 Bethune Street in Greenwich Village. The

Shahns lived on the two floors directly above Evans’s studio and

Shahn painted in his own living room.15 As Judith Shahn, the artist’s

daughter, recalled, “Evans was like a member of the family; he was

frequently invited upstairs for supper in the kitchen.”16 “For

Evans,” observed his biographer Berlinda Rathbone, “no one could

have been a better ally at that moment than the energetic and canny Ben

Shahn.”17 According to Bernarda Bryson Shahn, who met Shahn in 1933

and two years later became his wife, “Both artists initially enjoyed

each other’s witty, free-minded personalities.”18 Central to

their free-mindedness was a shared subversive attitude regarding established

bourgeois society. While Evans’s concern was geared more toward bourgeois

cultural prejudices, Shahn’s was toward art’s positive function

as ideological reformation.

Shahn had been interested in photography before he met Evans and began

taking pictures in the early 1930s.19 Amongst Strand’s early “straight”

photographs that register minute details and the subtle tonal ranges of

objects, his photographs of pedestrians especially impressed Shahn. “Learning

from Strand, Shahn often turned his attention to the individual in the

urban setting,” observed art historian Susan Edwards.20 Both Shahn

and Evans welcomed straight photographs to the extent that they later

discussed collaborating on a photography book in which they would oppose

both the artificiality of Pictorialist subjects such as female nude 21

and the blurry mechanism of the soft-focus Pictorialism. They rejected

romantic subject matter and idealizing techniques, but Shahn was further

drawn to the humanistic content of Strand’s early photograph and

its critical potential to reveal an underside of society.

In 1930, while working on the subject of The Dreyfus Affair,22 Shahn painted

two portraits of Evans. The portraits show expressive styles of Shahn’s

pre-photographic period. Shahn’s painterly representations of the

photographer suggest the complex nature of the two artists’ acquaintanceship;

for Shahn, a portrait meant the painter’s critical observation of

the sitter, rather than a flattering resemblance.23

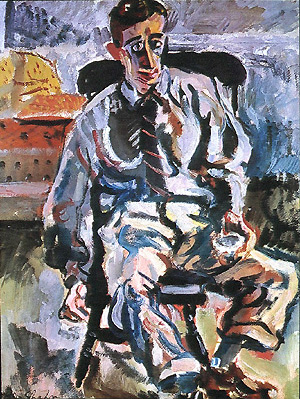

On the simplest level, the two portraits show Evans sitting on a chair.

One is painted in oil(fig. 1), the other in watercolor . The canvas of

the oil portrait is thickly painted with agitated brushstrokes in bright

colors. Evans, in a dress shirt, is arrested in an action while sitting

on a wooden chair with his legs spread and holding a camera lens, an evident

marker of his profession. The broad contouring used in some parts, the

freedom of brushstrokes, and the sporadically applied blue, orange, and

dark brown recall Georges Rouault’s early watercolors to which the

French painter often added pastel for heavy texture. In comparison, Shahn

shows clearer spatial order and emphasizes the fluidity of brushstrokes,

creating a more overall elegance than Rouault.

Shahn divided the watercolor portrait into three transparent color-patches:

blue, covering the area of the battered wicker chair and the upper body

of Evans; white, Evans’s trousers; and a light wash in pale yellow

of the surrounding area. While making each color-patch into a concrete

shape, the calligraphic and elliptical contours and linear details added

later not only give the patches vibrating rhythms, but also enliven the

freshness of each color without reducing the color to a function of simple

representation. Within this overall scheme, the torso of Evans is barely

distinguished by the few flowing lines from the chair in which he is slouching.

His shoulders are hunched and his hands are digging into his pockets.

The transparent colors and calligraphic linear details are associated

with Raoul Dufy’s painting; unlike the Fauve, who depicted figures

in a more stylized manner, Shahn emphasizes the individuality of the sitter.

Within both portraits, Evans’s likeness is captured through free

yet concise details. Evans’s sensitive or “squeamish”24

personality is suggested through his physiognomy, unique pose, and neat

costume. Hardly the idealized type of portraiture, the activated brushstroke

and bodily exaggeration evoke a sense of intense psychological and intellectual

exchanges between the painter and the sitter. Neither portrait contains

any obvious iconographic sign that proves Shahn’s critical apprehension

of the photographer, but Shahn’s expressive form and color connote

the essential difference embedded in their art; at this time Shahn chose

to reject formalist-modernism in favor of a more realistic representation

conveying concrete narrative contents. Shahn, who acknowledged in 1929

that “the French school is not for me,”25 baptized Evans with

the painterly style of the French school, colorfully characterized the

detached nature of Evans’s modernist aestheticism, and covertly differentiated

the photographer from himself.

|

During the summer of 1930, Shahn and Evans had a two-day

joint exhibition in the barn of a Portuguese neighbor on Cape Cod, where

they spent the summer. Shahn hung The Dreyfus Affair (fig. 4), a series

of works created specially for the exhibition and Evans exhibited his

photographs of the neighbors, the Deluze family.

The Alfred Dreyfus Affair, the case of the Jewish officer in the French

Army falsely accused of treason, shook France in the 1890s. Participating

in political protests in Paris over the more recent Sacco and Vanzetti

case in America (the trial of two anarchist Italian immigrants convicted

of murder on flimsy evidence), Shahn perceived the Dreyfus case to be

a similar conspiracy of the social system against ethnic minorities and

the working class.

To create The Dreyfus Affair, Shahn first used published photographic

images as models.26 From photographs in the relevant books, old magazines

and news articles, he painted the major players in the Dreyfus trial.

Fine details are added to broad washes of facial area and clothing to

characterize the faces and costume decorations. The backgrounds are left

empty or covered with a pale wash. Each portrait has the carefully lettered

name in different scripts, the hard edges of which are in sharp contrast

with the washed areas of a figure. Despite the quick application of washes,

each portrait shows proper bodily proportion, clear features, and additive

details drawn with exactness. The Dreyfus Affair demonstrates Shahn’s

magnificent graphic skill attained through lithographic training. The

shaded areas of the faces suggest volume and space, yet most of the portraits

are painted flat. The optical flatness is reinforced by the impersonal

arrangement of the letters. The shallow space and fine details are possibly

transferred from the photograph, in which abrupt changes of light and

shade often cause similar flat effects. The overall transparent colors

of The Dreyfus Affair, however, do not effectively emphasize the seriousness

of the historical trial. This lightness would disappear with the emphatic

patterns--the darker tonalities, nervously broken lines, and an undercurrent

of distortion--of The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti that he began to paint

the following year.

One of the Deluze photographs exemplifies Evans’s photographic treatment

of the subject. The interior scene shows a prickly cactus plant set against

the framed family photographs, a souvenir American flag, and a vase of

dried flowers. Through the straight photographic technique, both photographs

keep the same degree of descriptive exactitude for the objects from the

foreground to the background. Particularly in the photograph of the cactus

plant within an airless space, the equally distinctive contours and the

scattered dark areas, in strong contrast to the white wall, push the photographed

objects all-over to the picture plane. This reductive formal process of

the photographic still life helps objectify its content, the commonplace

American domestic space.

Taken slightly later, however, Hudson Street Boarding House Detail (1931-33)

shows an interior scene of a bedroom. In this bedroom picture, the decorative

quality is retained by the curvilinear patterns of the wrought-iron bed

and the black and white contrast of the bedspread and surrounding areas.

However, the shabby interior--the rough wall, the drooped curtains, and

the sunken mattress—reveals an economically dire situation. Here,

the decorativeness of this photograph collides with its unavoidable suggestion

of a specific relation to the outside world; this collision of formal

abstraction and social implication makes possible multiple ways of appreciation

and interpretation of the work. In this way, Evans refused to assign a

predefined meaning to his photography.

Evans’s emphasis upon the absence of the author was another unacceptable

point to Shahn, who was conscious of the artist’s social contribution

through critical interpretation and active involvement. In response to

Shahn’s arguments about the ideological function of art, Evans said:

“I wouldn’t let him touch or influence me. If he said I took

Depression pictures of human havoc, and I would say that was what I was

doing, I would walk out and wouldn’t let him discuss this.”27

In a detached manner, Evans frequently documented subjects that contained

specific social situations throughout his career, particularly in 1935

and 1936 when he was hired by the Resettlement Administration/Farm Security

Administration.

|

Despite the irreconcilable difference in their artistic

visions, Shahn would incorporate the less formalized type of Evans’s

early documentary photographs into his art. These photographs often fail

to embody objective approach, as Evans himself recalled: “In 1928,

‘29 and ‘30 I was apt to do something I now consider romantic

and would reject.”28 The oblique angle of these photographic studies

of people creates a perspectival recession that distracts the viewer from

direct visual confrontation with the photographic subject. In the late

Thirties, Shahn would use a similar diagonal composition in his own photographs

of ordinary people used for his “personal realist” work.29 For

instance, the subject of workers resting on the street, which Evans photographed

in 1928 or 1929 (fig. 5), is echoed in Shahn’s photograph, Sunday,

1937, and the same subject is again transformed into the painting, W.P.A.

Sunday, 1939.

By the early 1930s, Shahn must have fully appreciated Evans’s ambivalent

attitudes toward the variety of photographic themes. Despite the evident

differences in their early careers, Evans’s extensive experimentation

with photography offered an immediate and ample environment in which Shahn

became aware of the usefulness of photography for the representation of

realistic visual drama. Whereas Evans attempted to privilege photography

as a fine-art medium capable of embodying diverse formal and thematic

tendencies, Shahn integrated photographic images and details into his

painting to convey historically specific and ideologically critical narratives.

The portraits of Evans painted by Shahn at the moment of their stylistic

breakthrough suggest intimate, intense and critical dialogues between

the two young artists.