Exhibition Design as Installation Piece

by Vanessa Rocco

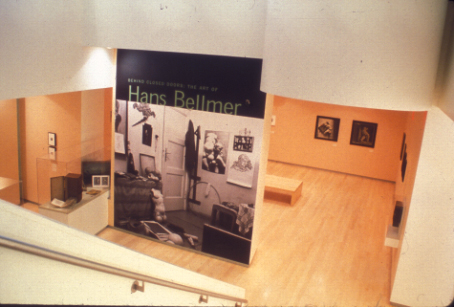

Behind Closed Doors: The Art of Hans Bellmer

International Center of Photography

March 29 – June 10, 2001

Exhibition Design as Installation Piece

The first North American retrospective of the German artist Hans Bellmer

(1902-1975) in the lower galleries of the International

Center of Photography was a press favorite. The New York Times, Village

Voice, Time Out, and New York Magazine all carried extensive reviews,

some publishing more than one article. The critics were clearly ready

for a treatment of this artist, best known for his construction and serial

photographs of two life-sized dolls in various guises and poses taken

between 1933-38. Surprisingly, despite all the attention, none of the

major reviews considered the role of exhibition design in this “site-specific”

installation at ICP, the only venue, other than to note that it was the

work of famed French designer Andrée

Putman. The assertiveness of her design warrants a deeper discussion

of its how its elements related to the displayed work.

Curator Therese Lichtenstein’s thesis was more focused than one typically

finds in a show designated as a retrospective. She was attempting to expand

the often limited understanding of Bellmer as an artist whose work’s

meaning is tied strictly to his private desires and borderline misogyny,

and whose discovery by André Breton in 1934 allowed him to be accepted

into the art historical canon as a Surrealist. In contrast, Lichtenstein

located Bellmer’s oeuvre within a cross-section of German political

and cultural influences in a way that allowed for social as well as biographical

interpretations of the work. Lichtenstein worked closely with Putman on

the concept of the exhibition and the presentation of the material was

an integral component to expanding the context within which Bellmer’s

work is interpreted.

The first section of Behind Closed Doors was entitled “Dolls, Mannequins,

Robots.” The emphasis was on Bellmer’s early career as a painter,

typographer, and illustrator in Berlin in the 1920s and early 1930s, where

he came under the influence of major Dada and New Objectivity artists,

such as George Grosz, Otto Dix, and Rudolf Schlichter. These artists were

responding to rapid cultural changes in Germany during the interwar period,

including intense industrialization, the increased presence of women in

the public sphere, and severe economic fluctuations. There were also significant

psychological developments in Bellmer’s life at this time, as he

became sexually obsessed with his adolescent cousin Ursula who had moved

next door. The progression of his fantasy life about her dovetailed with

his viewing a 1932 production of Jacques Offenbach’s “The Tales

of Hoffman.” In the first act, “The Sandman,” a girlish

doll named Olympia comes to life before the loving eyes of the protagonist,

Nathaniel.

A confluence of this early source material that led Bellmer to begin construction

of his first doll in 1933 was presented in the opening section with the

usual curatorial strategies of selection and juxtaposition: works by Dix

and Schlichter depicting prostitutes; newspaper clippings about the Hoffman

production; and German film stills documenting the popular but unsettling

subjects of automatons and robots in the face of industrialization. Through

various design elements there was also an attempt to show Bellmer’s

private collecting habits and his fascination with German and French erotica.

At the start of the exhibition, samples of contemporaneous erotic magazines,

postcards, and books on masochism of the kind Bellmer amassed were displayed

in tall vitrines, designed by Putman, which aggressively cut through the

architecture of the galleries (illustration 1). The printed material was

displayed spilling out of antique boxes, drawers, and cases. These usually

“closed” objects served as metaphors for the private nature

of the erotic images that preoccupied Bellmer and for the sexual nature

of his future work using dolls through which he would act out his fantasies,

social anxieties, and identity issues. 1 The boxes containing the erotica

echoed (anticipated?) the object viewers would see as they moved into

the next gallery: the Personal Museum, ca. 1938-70, is a display box Bellmer

began to put together and add to after his mother sent him a box of his

childhood toys in 1931. The toys were sent when his parents relocated

to Berlin from Gleiwitz after Bellmer’s autocratic father suffered

a cerebral hemorrhage, which proved to be another momentous event for

Bellmer in the early 1930s.2

|

|

Fig 2: Section 1, "Dolls,

Mannequins, Robots," with the Personal Museum, right,and Bellmer's

photographs, left, flanking the wall text.

|

In every section and room of this exhibition, Bellmer’s

photographs of both the first and second doll (completed in 1935) were

prominently installed, even in the gallery concerning early “pre-doll”

context. Lichtenstein and Putman wanted to be certain that the viewer

would always have Bellmer’s main works in mind when considering the

mediating influences. Bellmer produced at least thirty photographs of

the first doll, and one hundred of the second doll, each time changing

the pose, states of dress or undress, hair, accoutrements, and settings,

which included domestic interiors and outdoor scenes. The paint color

chosen for this first section was a sensual, fleshy peach. Combined with

the dolls, the erotica, and the lighting softened by colored gels, it

created the feeling of being in a boudoir, both lovely and somewhat forbidden

(illustration 2). Throughout the exhibition, the lighting-- in combinations

of pink, yellow, and orange-- picked up the colors of the hand-tinting

that Bellmer often used on the doll photographs. The gentleness of the

green and pink pastel tints seemed to mock the violent positions into

which he would twist the dolls, and Putman, along with her lighting designer,

Hervé Descottes, wanted to achieve a similar ambiguity in the installation.

The second section, “Bellmer in Nazi Germany,”

the crux of Lichtenstein’s thesis, was the most minimal in design

of the three. In this room the content was allowed to speak more directly

for itself. The paint was left a stark white, although the same lighting

scheme was used, this time either illuminating the works from below, or

by installing lighting directly into the walls of the main entrance of

the gallery (illustration 3), which maintained the sense of being in an

alternate realm. Here, the viewer initially confronted numerous images

of the first papier-mâché doll in poses varying from prostrate

and vulnerable, to coy, with over-the-shoulder glances. Two vitrines,

shorter and less dominating than the aforementioned erotica-filled cases,

contained the kind of Nazi propaganda to which Bellmer would have been

constantly subjected after Hitler took power in 1933. This propaganda

included a 1935 edition of the journal Das Deutsche Lichtbild (German

Photography), with photographs of healthy, tanned, Aryan youths, catalogues

from the Great German Art Exhibitions of 1936, 1937, and 1938, Nazi-sponsored

shows of sanctioned artwork, often highlighting Hitler’s favorite

sculptor of classical Greek rip-offs, Arno Brecker, and an original brochure

from the 1937 Degenerate Art Exhibition in Munich in which the Nazis tried

to lay out a cohesive argument that any art relying on primitivism, expressionism,

or pure abstraction was corrosive to a healthy society. This led Bellmer

to declare that he would no longer make commercial work that contributed

in any way to the economy of the fascist state and to retreat into the

studio to create a body of work that stood in stark contrast to the Nazi

program. His production was a self-proclaimed “remedy, the compensation

for a certain impossibility of living.”3

Examples of how Bellmer’s reaction to this repressive

environment leaked into his work were immediately accessible to the viewer

through the photographs of the second doll that were placed on walls adjacent

to the Nazi-era vitrines (illustration 4). The construction of this doll

was more complex than the first in that the center ball joint Bellmer

had fashioned with his brother Fritz could have numerous appendages attached

to it. He often photographed the doll with multiple legs, and in one piece

he hand-tinted angry red spots on the legs, making them look inflamed

with disease, and thus providing a foil to the sculpted bodies sprinting

through the Nazi magazine pages nearby. Directly behind the vitrines was

a disturbing image of the doll propped against a tree in the woods, with

the shadowy figure of a voyeur standing behind the tree. In a perfect

blend of social and private, the figure functions as a stand-in for Bellmer

and the fantasies he could act out on his dolls,4 but concomitantly

for the watchful and repressive regime within which he created work that

would be damned as degenerate if discovered.5

An element which allowed Putman to dramatically foreground

her design in this section was the crown jewel of the installation, the

actual second doll (La Poupée, dated 1932-45 due to elements of

the first doll being incorporated into the second) which was lent by the

Centre Georges Pompidou in France. The work was located in an intimate

room just beyond the gallery with the Nazi printed material and placed

on a platform made to look like a bed, with two blankets thrown over it

on which the doll and her double pair of legs rested (illustration 5).

Putman insisted that the blankets be the kind used for packing and shipping

artwork, for two reasons: Bellmer used the same type of padded, stitched

blankets as a backdrop for one of his strangest doll photographs, one

with the ball joint and a leg, a bow and blond hair, but no head, and

a long string with a detached eye (see illustration 37 in Lichtenstein);

also, the colors one often finds in these blankets are, like the dolls

themselves, a weird mix of sweet and ugly, like “piss yellow and

sucked-lollipop pink.”6 The platform was shrouded behind

a scrim, and the translucency of this material combined with theatrical

lighting installed along the bottom of the floor indulged the spectators

in voyeuristic pleasures, inviting them to peek into a forbidden zone

in order to get to the core element of the exhibition. Putman used a similar

setting (without the packing blankets) to display La Poupée in

the 1998 Guggenheim exhibition Guggenheim/Pompidou: A Rendezvous.

|

|

Fig 5: Plan your day to prevent

fatigue. Lillian Gilbreth sits at a desk she designed to help homemakers

plan their days, weeks, and months. [Photo: Gilbreth files, Purdue

University Library]

|

After encountering the grandiosity of La Poupée,

the viewer then moved into the third and final section, “Bellmer

and Surrealism.” Aspects of this section reflected those of the first:

pastel hues, this time in light green, and tall vitrines, although the

second time around the disconcertingly “pretty” color and huge

vitrines were not as jarring to the eye. The cases contained Surrealist

books and journals that bore Bellmer’s influence7 spilling

out of the boxes and drawers. Breton and Paul Eluard, the leading poets

of the Surrealist movement, were introduced to Bellmer’s work by

his adored cousin Ursula when she went to Paris to study at the Sorbonne.

She brought eighteen photographs of Bellmer’s first doll to Breton

and Eluard, who so admired them that they were published the same year

in Minotaure. The two poets understood that Bellmer’s project was

an attempt to explore the same subversive, sexual realm that they tried

to use in their work as an alternative to the dictates of bourgeois existence.

Since Freud’s sexually-based readings of the subconscious became

a powerful weapon for the Surrealists in this battle against the bourgeoisie,

the boxes, drawers, and valises that contained the Surrealist journals

carried as much metaphorical weight in this section as in the earlier

section with the erotica. Bellmer finally left Germany in 1938 after his

wife’s death, and came to Paris to join up with these kindred spirits.

In the 1940s he began collaborating with the renegade Surrealist, Georges

Bataille, on his book Story of the Eye. Original dry-point engravings

of the illustrations for the book were installed in wall vitrines toward

the end of the exhibition. Bellmer lived in France for the rest of his

life, and the section on Surrealism thus appropriately functioned as the

conclusion to the retrospective.

The most successful synthesis of design and content in Behind Closed Doors

was achieved in the first section and in aspects of the second. The heart

and soul of the exhibition’s thesis, namely that Bellmer’s art

was socially engaged, was illuminated in the middle section on “Bellmer

in Nazi Germany.” To that end, the contrast between the “diseased”

doll and “healthy” Aryans, as well as the presentation of the

doll, the object on which he worked out these ideas in the studio, were

critical revelations. However, the opening section was crucial in establishing

a more nuanced and variegated examination of what drove Bellmer first

to create these dolls and then to photograph them over and over. Erotica,

films, operas, childhood toys, social unease, adolescent crushes: these

sources and sensibilities coalesced in the early 1930s as the artist began

producing his unsettling and subversive oeuvre. The public met the private

in this exhibition, within a framework of German cultural realities in

the 1920s and 1930s. As an installation piece in and of itself, the first

section was a stunning achievement. All the tools of design were mustered

to engage the viewer with the contextual material: imaginative vitrine

design and installation, lighting, color scheme, and juxtaposition of

works with related ephemera.

Given the number of prizes (including the Grand Prix National de la Creation

Industrielle from the French Minister of Culture in 1995) and commissions

she has won, it is understandable that Putman’s name would be mentioned

by reviewers. But Behind Closed Doors did, quite literally, recreate the

history of Hans Bellmer, and the design actively interpreted that historical

material. In the future, let’s hope exhibition design will be treated

more vigorously by reviewers.

Behind Closed Doors: The Art of Hans Bellmer has been named Photography

Exhibition of the Year by the International Association of Art Critics,

and one of the Best of 2001 by Artforum.