| |

|

|

|

| |

Emil Bisttram: Theosophical

Drawings

by Ruth Pasquine |

| |

|

| |

Intellectualizing Ecstacy: The

Organic and Spiritual Abstractions of Agnes Pelton (1881 - 1961)

by Nancy Strow Sheley

|

| |

|

| |

Stuart

Davis' Taste for Modern American Culture

by Herbert R. Hartel, Jr. |

| |

|

| |

Jean Xceron:

Neglected Master and Revisionist Politics

by Thalia Vrachopoulos |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

"Delusions of

Convenience": Frances K. Pohl, Framing America: A Social History

of American Art and David Bjelejac, American Art: A Cultural History

by Brian Edward Hack |

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

Wanda

Corn, The Great American Thing, Modern Art and National Identity,

1915-1935

by Megan Holloway |

| |

|

| |

The

Impact of Cubism on American Art, 1909-1938

by Nicholas Sawicki |

| |

|

| |

Celeste

Connor, Democratic Visions: Art and Theory of the Stieglitz Circle,

1924-1934

by Jennifer Marshall |

| |

|

| |

Pat Hills,

ed. Modern Art in the U.S.A.: Issues and Controversies of the 20th

Century

by Pete Mauro |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

| |

"Most artists

are with you and that is the greatest level of appreciation."

-David Smith to Jean Xceron

1

|

|

|

Jean

Xceron (1890-1967) was an American modernist pioneer who in his

lifetime enjoyed renown and was regarded as a forerunner to American

abstraction but who, for numerous reasons, has fallen into obscurity.

Whereas he had gained a measure of success in his lifetime, since

his death his importance has faded while his impact on other American

artists has been trivialized. The resulting lacuna of data

combined with some fragmentary misinformation has also served

to suppress his significance. Xceron's role as a vital link

between what is commonly termed as the first-generation (the Stieglitz

group, the Synchromists, etc.) and second-generation (the American

Abstract Artists, the Transcendental Painting Group, George L.K.

Morris, Ibram Lassaw, etc.) of abstract artists in America2

and between the Parisian Cercle et Carré, Abstraction Création

and the American Abstract Artists groups in the thirties, should

be recognized. The division between first and second generation

American abstraction is a false one, resulting in the ironic belief

that there was a break in American abstraction between the World

Wars. As evinced by the existence and work of masters such

as Xceron,3 Arshile Gorky, Raymond Jonson, John Graham

and many others, American abstraction never actually died out

but became less popular between the World Wars. Furthermore,

because Xceron's early works are unknown, he has been characterized

by his best known, more familiar post-1940s style, which has been

described as rectilinear, grid-like or Mondrianesque, another

irony.4 Consequently, Xceron has been placed within

the category of second-generation American abstraction and his

earlier accomplishments have been rendered obscure. However,

a re-examination of the early sources and the recent discovery

of Xceron works from the early 1930s reveals he was continuously

creating abstract works from 1916 to 1932. After this period,

Xceron's style became purely abstract and remained so for the

rest of his life. In reviewing these thorny issues for the

purpose of rectifying some commonly held misconceptions, the author

hopes to clarify Xceron's meritorious role and its context in

American art, and to bring about a better understanding of his

painting.

Xceron's

given name was Yiannis Xirocostas. He was born in 1890 in

Isary, Greece, and came to the United States in 1904 at the age

of fourteen. He lived with various relatives across the country

until 1911-1912, when he began studying at the Corcoran School

of Art in Washington, D.C. His surname was eventually changed

to Xceron. He was called John (the English equivalent of Yannis)

in America and Jeanduring the years he spent in France.

In 1913, Xceron and his classmates Abraham Rattner, Leo Logasa

and George Lohr, were deeply affected by the innovative style

of the modern works in the Armory Show. In the Armory Show's

aftermath and after several traveling venues some works from this

show went to Alfred Stieglitz, whose gallery at that time was

one of the few to champion modernism. Xceron and his colleagues

borrowed some of the Armory Show works from Stieglitz to mount

their own version of the show in Washington, D.C.5

Consequently, Xceron and his cadre earned reputations as revolutionaries

for attempting Cézannesque interpretations of their subjects

rather than following prescribed academic methods.

After

graduating from the Corcoran, Xceron went to New York to study

independently, and by 1920 was exhibiting with the Society of

Independent Artists and associating with its member artists Joseph

Stella, Max Weber, and Abraham Walkowitz. A representative

work of that period is Landscape #36, 1923, a gouache on

board, which is a study after Cezanne that demonstrates Xceron's

expertise with transparent space that would be recognized as a

key characteristic of his mature style. A cottage in the

woods is depicted in passages of brown, green, and neutral shades

and exhibits various figure-ground ambiguities as a result of

the interchangeability of the rectangular strokes. The tree trunks

on the right of the composition are clearly read as foreground

whereas the tree shapes on the left appear to be in the middle

ground and to pull towards the back. The flatness of the cottage

and the adjoining trees seemingly growing from its gabled roof

render an ambiguous reading. The overall effect is one of veils

of transparent color as if the forest has been draped with delicate

chiffon material.

Xceron

should have been recognized in the scholarly literature as part

of this early American avant-garde, but because his documents,

records and early works had been lost or became otherwise unavailable,

he has remained relatively unknown. More recent scholarship

and uncovered sources of personal archives show that Xceron was

familiar with the international artistic milieu as well.

One of these artists was the Uraguyan Joachin Torres-Garcia, with

whom he corresponded after Torres-Garcia went to Paris in the

early twenties. In 1930, when Xceron went to Paris, Torres-Garcia

invited him to join his newly formed group the Cercle et Carré.

Kimon Nikolaides, Xceron's Corcoran colleague who became a well-known

Art Students League teacher, invited Xceron to deliver a lecture

on abstraction at the League.7 Xceron's link

to this school is important because several of its members would

have a future impact on the Abstract Expressionists. And,

directly (through the Garland Gallery Exhibition and through his

images in Cahiers d'Art) and indirectly (through his connections

to the teachers of the League) so would Xceron. But whereas

the latter has never been studied for his influential role, Graham

recently has been found to be of seminal importance to Arshile

Gorky and Willem de Kooning.

Another

important event in Xceron's life in New York during the twenties

was meeting the Greek Dada poet Theodoros Dorros, who inspired

him to break further with his academic past. Dorros, a mysterious

character in the true sense of the Duchampian Dada spirit, was

a Socialist who wrote Dada poetry, which he published himself

so that he could maintain an independent voice. He was known to

present gift copies of his poetry books to libraries as he did

to the New York Public Library in order to promote his beliefs.8

He is recognized in Greece as a Dada forerunner but there is still

very little information available on this Greek poet.9

Concentrated research has revealed that while supporting himself

as a tailor in the family's fashion business in New York and its

subsidiary in Paris, he wrote both Dada poetry and socialist literature.

Because the Dorros family owned a fashion concern and had roots

in Paris, he was able to help Xceron when the artist arrived in

that city, and introduced him to his sister Mary, whom Xceron

married in 1935.

Perceived

as too pragmatic, materialistic and commercial by many artists,

the atmosphere of New York in the twenties became constricting

to these modernists -- some of who sought alternatives in Paris.

Xceron and Torres-Garcia were two such artists seeking a more

amenable working climate; less invested in materialism and more

agreeable to artistic concerns. In 1927, with many letters

of introduction including one from Abraham Rattner who knew the

editor of the Herald Tribune, and the help of the Dorros

family, Xceron went to Paris to further his career. Initially

he wrote art reviews as a syndicated art columnist for the European

editions of the Chicago Herald Tribune, BostonEvening

Transcriptand New YorkHerald Tribune, newspapers which

were widely read by Americans abroad as well as at home.

Therefore, Xceron's role as disseminator and link between the

Parisian and American avant-gardes actually began as an art critic.

He not only reported on but became acquainted with Julio Gonzalez,

Jean Arp, Sophie Teuber Arp, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Natalie

Goncharova, Piet Mondrian, El Lissitzky, Theo Van Doesburg, Michel

Larionov, and Vasily Kandinsky. He also announced such events

as exhibitions, performances, recitals, and concerts.10

Through

the Greek Diaspora in Paris Xceron came in contact with the Christian

Zervos coterie and was introduced to Juan Gris and Efstratios

Tèriade. Tèriade wrote about his work and gave him

entrée to many other prestigious circles.11

By 1928, Xceron exhibited several abstracted nude studies at the

Galerie Dalmau in Barcelona with friends from Paris including

Jean Hélion and Torres-Garcia. Xceron's 1931 one-man

show at the Galerie de France was so well attended and successful

in its critical reception that it signaled the inception of Xceron's

artistic renown. It was also at this juncture that Xceron's

name and works began appearing regularly in the French press,

especially in L'Intransigeant and Zervos's Cahiers d'Art.

Tèriade, Zervos, André Salmon and Maurice Raynal,

four of the most important art critics in Paris in the early thirties,

wrote reviews of Xceron's biomorphic works made at this time.

Two particular works, both entitled Peinture, and done

in oil on canvas in 1932-1934, were reproduced in Cahiers d'Art12

Xceron's biomorphic abstractions and collages were informed not

only by natural processes (as were Jean Arp's concretions)

but also contained the elements of chance and automatist gesture

found in Dada. It should be pointed out here that the earlier

experience with the Dada poet Dorros was seminal in this regard.

But, Jean Arp's work also inspired him and he had reviewed Arp's

show in the July 20th, 1929 issue of the Chicago

Tribune. The importance of Xceron's biomorphic pieces

increases exponentially when considered as typical examples of

his early thirties style, which is Dadaist. It also serves

as proof that Xceron's biomorphic works inspired American artists

such as Arshile Gorky, David Smith, and William Baziotes, who

were known to read the Cahiers d'Art in which Xceron's

work was often reproduced.One seminal figure that brought

these publications back to the United States for other American

artists to read was John Graham, with whom many of the Art Students

League circle were acquainted. In fact, Graham traveled

to Paris very often and used Xceron's address to receive his mail.

The proximity of these two artists resulted in a medley of erroneous

conclusions mistaking one John for the other and causing some

misattributions. To complicate things further, Hilla Rebay, then

the director of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now known

as the Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum of Art), employed both John

(in French Jean) Xceron and John Graham. Consequently,

American critics often confused the two painters and attributed

credit to John Graham for David Smith's biomorphic or Surrealist

influences while a closer inspection of the documents and a re-examination

of dates and facts renders proof that it was Xceron whom Smith

was thanking in his letters for Xceron's influence and advice.13.

An

event of special significance to American artists in 1935 was

Xceron's Garland Gallery exhibition, but the reasons for this

success are not immediately evident until the art and political

contexts of New York in 1935 are scrutinized.14 Then

it is discovered that exhibitions containing abstract art, such

as Xceron's, were rare events and that American artists were eager

to see the latest styles from Paris. The Depression had

taken its toll and the prevalent artistic styles were figurative,

while abstraction was still considered experimental and unsuitable

for expressing political polemic. The brothers Max and Joseph

Felshin, early advocates of abstraction, owned the Garland Gallery

on 57th Street. But since the gallery's closing

in the early forties, the Felshins have fallen into obscurity,

leaving us with very little documentation on the history of this

space. In fact, only a careful reconstruction of the events

from various archives rendered proof of which Xceron works

were shown at the Garland, what was their style, and what were

some of the names of those who attended the events. In discovering

the Felshin paintings Composition 120, 1934 (Fig. 1) and

La Musique, 1933, it is evidenced that Xceron was working

in abstract biomorphism foreshadowing many Americans, such as

Gorky, and that stylistically and chronologically these paintings

are consistent with those of the same period in the Zervos Collection.

However, Xceron's impact on American artists can be found not

only in the numerous interviews and writings by Ilya Bolotowsky,

David Smith, and Borgoyne Diller, but also in comparisons between

their works and his.15 As an avant-garde exhibition

of the latest styles from Paris, the 1935 Xceron show at the Garland

garnered profuse press reviews. Some of these were very positive

and most demonstrated the contextual proclivity for figurative

models of art which, rather than hindering the reception of Xceron's

work, made it all the more appealing to abstract artists in America.

That Xceron also enjoyed some commercial success at this time

is seen by the addition of his works to Eugene Gallatin's Museum

of Living Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Phillips Memorial

Collection. In addition, the artist also held the distinction

of being one of the earliest abstractionists to be offered a position

with the WPA/FAP at its inauguration in 1935, in Washington, D.C.;

but rather than accept it, he returned to Paris for another two

years.16

|

|

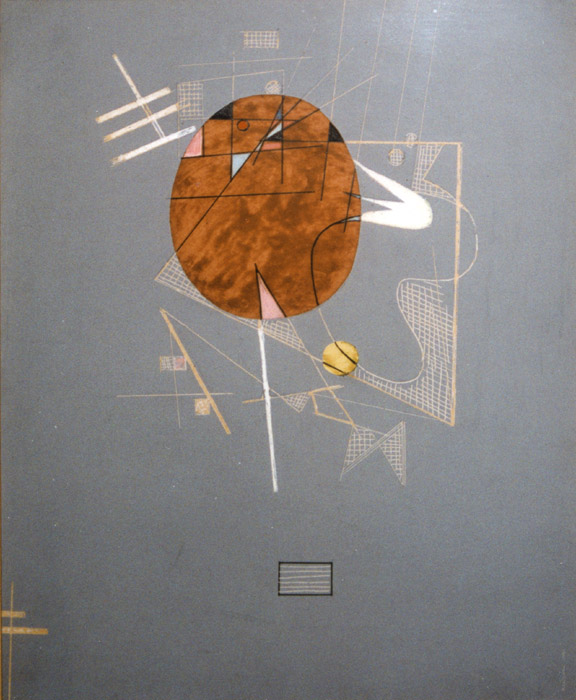

Fig

2: Collage. 1932

|

|

|

Fig

3: Composition No. 242, 1937

|

The

year 1937 signified a period of great success for Xceron as numerous

American artists sought his advice. Triumph after triumph

followed as Xceron was patronized by such influential figures

as Alfred Barr Jr., who collected his work for the Museum of Modern

Art, Russel C. Parr and Holger Cahill, whose recommendations to

the FAP/PWA resulted in the Riker's Island mural commission, and

Rebay, who as director of the Museum of Non-Objective Art, employed

him to work for the museum as custodian (the equivalent of a registrar

today) of paintings. Rebay had supported Xceron's studies

abroad since 1930, and had bought several works from his 1937

Nierendorf Gallery show that further promoted his fame among modern

American art audiences. Composition No. 242, 1937

(Fig. 3) was one of the works she purchased from the Nierendorf

exhibition for Solomon R. Guggenheim.

Xceron

had always been ambivalent about joining any group and usually

remained at its periphery, but due to his affiliation with Rebay,

he was even more divided about becoming a member of the American

Abstract Artists. Nevertheless, he joined them in 1938 but did

not show with them with any regularity. Rebay had supported

him financially, employed him, promoted his career and deserved

his loyalty, but was at ideological odds with this group.

A public debate ensued as the American Abstract Artists collectively

objected to Rebay's "ivory tower" aesthetics stating that abstract

art is part of life: "having basis in living actuality." 19

The political climate of the United States in the late thirties

and early forties was not sympathetic to abstraction, and pandered

to public opinion informed by the need to express clarity and

national values. Consequently, American abstract artists

felt unsupported by the Museum of Non-Objective Art, whose collection

contained works idiosyncratically defined by Rebay as "non-objective"

art, and the Museum of Modern Art, which owned mostly European

works. They also felt betrayed by the public who preferred

figuration. Abstractionists were criticized for being apolitical

or unpatriotic because their styles were perceived as incapable

of expressing political ideology. Abstract artists objected

to Rebay's idiosyncratic use of the term "non-objective" to define

abstract art. 18 An example of the negative press

Rebay received was written by Charles Robbins, who claimed to

represent public sentiment: "As a glance at the examples on this

page will show, non-objective painting to the uninitiated, looks

like a cross between a doodle and a blueprint drawn by a cockeyed

draughtsman on a spree." 19 Difficult as that

period was for Xceron and American abstract artists, and despite

his problematic and precarious political situation, he was an

important link between American and European art when many European

artists (such as Leger, Mondrian, and Hélion) immigrated

to America as Fascism rose in Europe. Many of them joined

the American Abstract Artists. This group was known for

its proclivity towards a rectilinear style inspired by Mondrian

who immigrated to the United States in 1941 and who joined this

group. In the forties, Xceron was also working in a linear

style, but not with pure colors as Mondrian and not in strict

geometry. Nevertheless, American audiences are most familiar

with this period of his work, ergo the assumption that he was

a follower of Mondrian. It was to Xceron that Mondrian first

wrote for help when fascist Europe became too dangerous for artists

to stay. In the end, Xceron could not invite Mondrian, who

was aided by Harry Holtzman instead, but they remained friends

from their Paris days in 1928 until the older master's death in

1944. A typical Xceron composition is an oil on canvas such

as Painting #294of 1946 (Fig. 4), in which the artist's

rectilinear preferences of that era are seen in the grid-like

elements both at the top and bottom left sectors. However,

unlike the flat, opaque, coloristic tendencies in Bolotowsky's

or Diller's paintings, Xceron's modulated shades of plum and lilac

fade into the distance to imply transparent space.

|

|

Fig

4: Painting #294, 1946

|

In

the forties and fifties, Xceron was the custodian of paintings

for the Guggenheim Museum, whose collection was housed at a Manhattan

warehouse. He was allowed to paint there in his spare time

while also receiving many visitors. Mark Rothko, David Smith,

Ibram Lassaw, Ilya Bolotowsky, Will Barnet, William Baziotes,

and Nassos Daphnis are some of the many artists to whom Xceron

showed his and the Guggenheim's paintings. Most were familiar

with Xceron's work through their reproduction in Cahiers d'Artand

the 1935 Garland Gallery show. Xceron enjoyed many solo

exhibitions and was included in most of the Guggenheim non-objective

painting group exhibitions throughout his life. The artist

also showed with such venues as the American Abstract Artists,

American Federation of Artists, Carnegie Institute, Federation

of Modern Painters and Sculptors, International Council of the

Museum of Modern Art, Salon de Realités Nouvelles, Salon

des Surindependants, Society of Independent Artists, Toledo Museum

of Art, University of Illinois, and the Whitney Museum of American

Art. By 1946, Xceron had achieved further prominence and

was commissioned by the University of Georgia to do a painting

that he entitled Radar(Fig. 5), which reflects the contemporary

interest in the marriage of art and science. 20

This oil on canvas encapsulates Xceron's oeuvre up to that time

due to its softly modulated floating spatial organization, which

contains positive and negative circular geometric and gestural

forms radiating out that are echoed throughout its surface.

This important work was widely publicized and marks Xceron's active

engagement with the style that would later become known as Abstract

Expressionism.

|

|

Fig

5: Radar, 1946

|

Finally,

through contextualization and examination of newly found key works,

the author hopes that Xceron's contributions to American art between

the World Wars has been clarified, bridging the falsely created

gap in American abstraction between the assumed division of first

and second generations. The detection of the Zervos Dada

automatist works in addition to the Felshin surrealist pieces,

along with the recently found documents, have supported Xceron's

position in early American abstraction, and have proved that American

abstraction certainly never died but rather that its popularity

sometimes waned. Xceron created art in an abstracted style

starting in 1916 while at the Corcoran, and by 1927 he had engaged

in automatist drawings and collages, resulting in total abstraction

by 1933-34 in the Zervos and Felshin works. As such, he

is one of the enduring masters of American modern art who persevered

in his engagement with abstraction up to his death in 1967.

Notes>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|

|