| |

|

|

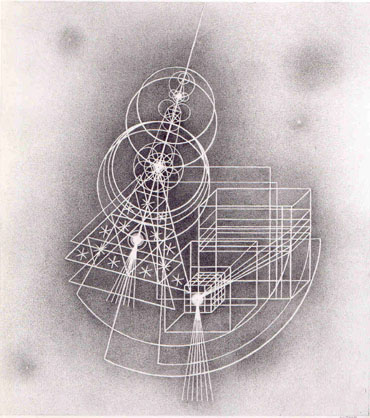

Fig 1: Time Cycle

No. 1, n.d.

|

Emil Bisttram (1895-1976) became interested in Theosophy in New

York in the 1920s, when he was first establishing himself as an

artist. His knowledge of the subject was enhanced by his relationships

with some of the most prominent Theosophists of the time, including

Claude Bragdon (1866-1947), Nicholas Roerich (1874-1947), and Manly

P. Hall (1901-1990).1 At the same time he became interested

in Dynamic Symmetry, a system of picture composition based on Euclidean

geometry, developed by Jay Hambidge (1867-1924). Intrigued by the

Theosophical axiom that religion and geometry are integrally related,

Bisttram developed an approach to painting--which he fully explained

in his teaching curricula--that brought the two systems together.

When Bisttram settled in Taos, New Mexico, in 1931, he found a receptive

audience for his ideas on Theosophy and spirituality, but a mixed

reaction to Dynamic Symmetry.2

In 1938, when he proposed the idea of founding what would become

the Transcendental Painting Group (TPG) to his three students, Horace

Pierce (1914-58), Florence Miller (b. 1918), and Robert Gribbroeck

(1906-1971), spirituality was central to his concept. Bisttram brought

in the Santa Fe painter and architect William Lumpkins (1910-2000),

who then proposed the idea in Santa Fe.3 Bisttram's

good friend Raymond Jonson (1891-1982) became the most active member;

his primary contribution was expanding and solidifying the membership,

bringing in the Canadian painter Lawren Harris (1885-1970), the

California painter Agnes Pelton (1881-1961), the New Mexico painter

Stuart Walker (1904-1940), and Dane Rudhyar (1895-1985) and Alfred

Morang (1901-1958) as writers to publicize the TPG. Harris, Pelton,

and Rudhyar were all avowed Theosophists.4

Harris was a well-heeled Canadian painter whom Jonson met in Santa

Fe in March 1938, while Harris and his wife were traveling cross-country.

Bisttram and Harris struck up a close friendship at this time, and

Harris took a number of classes on Dynamic Symmetry with Bisttram.

Bisttram had studied with Hambidge in New York in the early 1920s,

and Harris, who like Hambidge was Canadian, was already familiar

with Dynamic Symmetry. Bisttram's spiritual interpretation and application

of Hambidge's system must have been a strong factor in their friendship,

especially since Harris acquired Bisttram's drawing Time Cycle

No. 1, n.d. (Fig. 1), one of Bisttram's more complex uses of

the system.4 While the circumstances under which Harris

acquired this drawing are not exactly known, the spiritual dimensions

of the drawing serve as an example of the type of work that the

TPG members were interested in.

This drawing uses primary geometric forms--circles, equilateral

triangles, squares, and cubes-to express the creative-destructive

forces within the universe, and to depict relationships between

time and space as well as between life and death. Bisttram provides

the following interpretation for this drawing:

Time Cycle No. 1 is also one of a series resulting from

meditations on time and space. In this particular drawing the

lines of force or energy permeating space, manifesting out of

one source, having passed through the various organizing centers,

take on the geometric shapes of our world before matter condenses

or crystallizes on them. At the same time the drawing has the

suggestion of a pendulum in the shape of a scythe, a reaper swinging

in eternal space.6

The creative aspect of the forms is expressed by the descending

series of circles, triangles, and squares. This series follows Theosophical

theory, which postulates that creation is a geometrical progression,

beginning with a point. H. P. Blavatsky (1831-91), the most important

exponent of Theosophy in modern times, expressed this idea by citing

Pythagorean theory, one of the foundations of her approach:

In the Pythagorean Theogony the hierarchies of the heavenly Host

and Gods were numbered and expressed numerically. Pythagoras had

studied Esoteric Science in India; therefore we find his pupils

saying "the monad (the manifested one) is the principle of

all things. From the Monad and the indeterminate Duad (Chaos),

numbers; from numbers, Points; from points, Lines; from lines,

Superficies; from superficies, Solids; from these, solid Bodies,

whose elements are four: Fire, Water, Air, Earth; all of which

transmuted (correlated) and totally changed, this world consists."--(Diogenes

Laerius in Vit. Pythag.)7

Bisttram's involvement with Theosophy and Dynamic Symmetry

led him to his interest in Kandinsky's use of geometric form,

since it seemed to him that Kandinsky's book Point and Line

to Plane (1926) echoed this basic Theosophical tenet. By utilizing

a scythe in his image, Bisttram also expresses the idea that death

is the complement of creation, and that the two working together

alternately define the cyclic nature of time. A source for the symbolism

of the scythe is found in Max Heindel's The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception

(1909), a book which Bisttram studied closely.8 Max Heindel

(1865-1919), founder of the Rosicrucian Society in Oceanside, California,

commented on the scythe as follows:

This is the law that is symbolized in the scythe of the reaper,

Death; the law that says, "whatsoever a man soweth, that

shall he also reap." It is the law of cause and effect, which

rules all things in the three Worlds, in every realm of nature-physical,

moral and mental. Everywhere it works inexorably, adjusting all

things, restoring the equilibrium wherever even the slightest

action has brought about a disturbance, as all action must...

The law we are now considering is called the law of Consequence.9

Heindel is referring here to the law of karma. Heindel connects

the scythe with the concept of reincarnation by referring to it

as a symbol of the harvest of the permanent atom or Seed-Atom that

occurs at the time of death. This atom becomes the basis for the

individual in his next life:

So man builds and sows until the moment of death arrives. Then

the seed-time and the periods of growth and ripening are past.

The harvest time has come, when the skeleton spectre of Death

arrives with his scythe and hour-glass. That is a good symbol.

The skeleton symbolizes the relatively permanent part of the body.

The scythe represents the fact that this permanent part, which

is about to be harvested by the spirit, is the fruitage of the

life now drawing to a close. The hour-glass in his hand indicates

that the hour does not strike until the full course has been run

in harmony with unvarying laws. When that moment arrives a separation

of the vehicles takes place. As his life in the Physical World

is ended for the time being, it is not necessary for man to retain

his dense body. The vital body, which, as we have explained, also

belongs to the Physical World, is withdrawn by way of the head,

leaving the dense body inanimate. The higher vehicles--vital body,

desire body and mind--are seen to leave the dense body with a

spiral movement, taking with them the soul of one dense atom.

Not the atom itself, but the forces that played through it. The

results of the experiences passed through in the dense body during

the life just ended have been impressed upon this particular atom.

While all the other atoms of the dense body have been renewed

from time to time, this permanent atom has remained. It has remained

stable, not only through one life, but it has been a part of every

dense body ever used by a particular Ego. It is withdrawn at death

only to reawaken at the dawn of another physical life, to serve

again as the nucleus around which is built the new dense body

to be used by the same Ego. It is therefore called the "Seed-Atom."10

While this quote suggests that there is only one Seed-Atom harvested

at the end of a life, later in the text Heindel explains that there

are a number of Seed-Atoms; one, in fact, for each of an individual's

vehicles. What I am suggesting, then, is that the bright spots in

the centers of the major forms of Bisttram's composition depict

these Seed-Atoms that are about to be harvested by the scythe at

the end of a life. The ne in the center of the cube and the one

in the center of the triangle are specifically marked with "tails"

of seven lines each. Also, there seems to be a type of Seed-Atom

in the center of the circular form that marks the handle of the

scythe.

This interpretation leads more provocatively, however, to the conclusion

that Bisttram's series of geometrical forms is meant to represent

an individual. This is confirmed in Theosophical theory which conceives

of man as a sevenfold being, diagramed as a triangle supported by

a square. Blatvasky, indeed, diagrams man in just this way. She

labels the upper three parts as: 1. Universal Spirit (Atma); 2.

Spiritual Soul (Buddhi); 3. Human Soul, Mind (Manas); and the lower

four as: 4. Animal Soul (Kama-Rupa); 5. Astral Body (Linga Sarira);

6. Life Essence (Prana); 7. Body (Sthula Sarira).11

Bisttram's use and placement of the triangle and square and

the presence of seven tails on the Seed-Atoms within the triangle

and square would seem then to refer to Blavatsky's concept

of man. Additionally, the moving scythe seems like it is about to

bring the square into alignment underneath the triangle. This seems

to refer to the concept of geometrical alignment articulated by

the Theosophist Alice Bailey (1880-1949) in her book Letters on

Occult Meditation (1922):

The aim of the evolution of man in the three worlds--the physical,

emotional and mental planes--is the alignment of his threefold

Personality with the body egoic, till the one straight line is

achieved and the man becomes the One.Each life that the Personality

leads is, at the close, represented by some geometrical figure,

some utilisation of the lines of the cube, and their demonstration

in a form of some kind... The Master is He Who has blended all

the lines of fivefold development first into the three, and then

into the one. The six-pointed star becomes the five-pointed star,

the cube becomes the triangle, and the triangle becomes the one;

whilst the one (at the end of the greater cycle) becomes the point

in the circle of manifestation.12

|

|

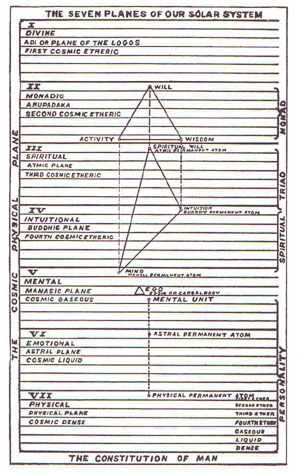

Fig 2: This chart is

labeled on the top The Seven Planes of Our Solar System and

on the bottom The Constitution of Man

|

In the same book she also discusses Seed-Atoms or permanent atoms,

and provides a chart showing their location (Fig. 2). This chart

is labeled at the top The Seven Planes of Our Solar System and at

the bottom The Constitution of Man.13 The titles refer

to the Theosophical concept of man as a microcosm of the cosmic

macrocosm. In this diagram she draws a triangle connecting the atmic,

buddhic, and mental permanent atoms. The three angles of the triangle

are 40, 110, and 30 degrees respectively. Measuring the triangle

formed by the three permanent atoms in Bisttram's drawing,

we find angles of 30, 120, and 30 degrees, essentially Bailey's

triangle reversed right to left.

According to Bailey, an individual operates, or is "polarised,"

by different permanent atoms at different periods of his life; when

an individual operates at the level of the three higher permanent

atoms, he is "a Master of the Wisdom."14 I

suggest that in Time Cycle I, Bisttram is depicting man as the microcosm

of the cosmic macrocosm, as well as man at his most evolved--operating

at the highest possible level at the time of his passing.

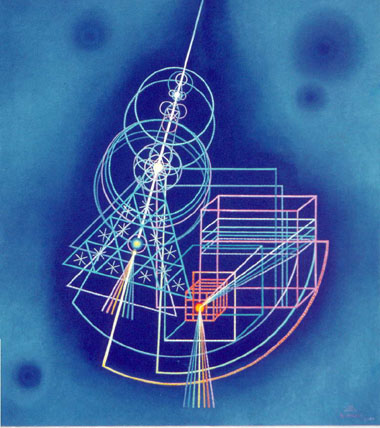

Another indication that Bisttram was studying Bailey can be seen

in his use of color, when he later executed this drawing in oils

(Fig. 3). In this same book, Bailey includes a section on color

that gives a list of "the seven streams of colour by which

manifestation becomes possible": 1. Blue, 2. Indigo, 3. Green,

4. Yellow, 5. Orange, 6. Red, 7. Violet. Bisttram used this color

sequence for both of the seven-rayed tails of the permanent atoms.

It is an unusual sequence because the expected order would be that

of the spectrum, with purple on one end and red on the other. Also,

Bailey associates blue, the dominant color of Bisttram's painting,

with the perfected man and the auric envelope through which he manifests,

as well as with the auric egg and the Solar Logos.15

|

|

Fig 3: Another indication

that Bisttram was studying Bailey can be seen in his use of

color, when he later executed this drawing in oils

|

Bisttram's treatment of the square as a cube within a cube

also relates to Claude Bragdon's theory of the fourth dimension.

Bisttram knew Bragdon in New York, and used his books as texts in

his classes in Taos. Bragdon, following Blavatsky, used the circle,

equilateral triangle, and square as the units of creation, explaining

that "the circle is the symbol of the universe; the equilateral

triangle, of the higher trinity (atma, buddhi, manas); and the square,

of the lower quaternary of man's sevenfold nature."16

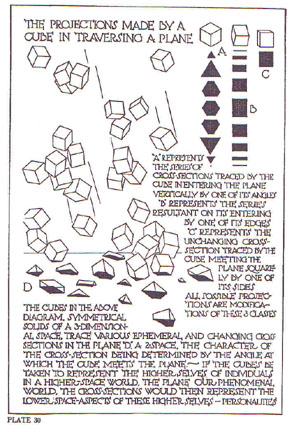

Bragdon based his theory of the fourth dimension on the problem

of transforming the square into the cube as a diagram of the process

of redemption. For Bragdon, the upper portion of a cube is heaven

(the fourth dimension) and the lower portion is the world as we

know it. Man the microcosm is the cube in his ideal (archetypal)

form; as man descends into incarnation from the upper part of the

cube to the lower part, he becomes a square. When descending into

incarnation, the square is distorted by the angle by which it enters,

producing the distortions of the individual personality (Fig. 4).17

The goal of the individual is to square up his life and to eventually

become the cube. Bragdon diagrams the fourth dimension as a cube

within a cube a metaphor for man the square rolling himself up,

as it were, back into a cube within the larger universal cube.18

Bragdon takes this idea from Blavatsky:

As those Alchemists have it: -- "When the Three and the Four

kiss each other, the Quaternary joins its middle nature with that

of the triangle," (or Triad, i.e., the face of one of its

plane surfaces becoming the middle face of the other), "and

becomes a cube; then only does it (the cube unfolded) become the

vehicle and the number of Life, the Father-Mother seven."19

|

|

Fig 4

|

By using Bragdon's symbol of the cube within the cube, Bisttram

injects the idea of the fourth dimension into his drawing. Additionally,

by connecting the series of squares with the center of one of the

circles, Bisttram describes life as a cycle that emanates from and

then returns to the Godhead.

As in all of his works, Bisttram used Hambidge's system of

Dynamic Symmetry in the organization of this drawing. His general

approach was to first do a freehand sketch of his idea, and then

afterwards bring the design into geometrical proportion using Dynamic

Symmetry. He began this process by establishing the major diagonal,

which in this case is the handle of the scythe (Fig. 5, line AB).20

He then constructed the rectangle (ABCD) around this diagonal. In

this case he then drew another rectangle of the same size (ADEF)

next to it.

The next operation is to divide the rectangles into what Hambidge

called reciprocals, that is, smaller rectangles that are proportional

to the whole. This is done by drawing a diagonal line perpendicular

to the major diagonal, and then drawing in the horizontal. This

procedure is repeated until the rectangle is divided into a series

of rectangles that are proportional to the whole. Each rectangle

can be divided into smaller units, and verticals can be drawn through

intersecting points without sacrificing proportionality.

Since photographs are inaccurate, and I am working at a smaller

scale, my lines are undoubtedly inaccurate. What is accurate, however,

is the perpendicular relationship between the base lines of the

triangles and the major diagonal. Indeed, this process of coordinating

verticals and horizontals with diagonals using geometric proportion

is the means and aim of Dynamic Symmetry. The principal tension

in the drawing is between the primary diagonal of the handle of

the scythe and the horizontals and verticals of the cube and squares.

The relationship between the two is mediated and resolved by the

triangles, whose bases, following the rules of Dynamic Symmetry,

are perpendicular to the primary diagonal.

Hambidge's method sets up proportional areas in rectangles

following the laws of Euclidean geometry. In his system he constructs

specific rectangles that relate to each other geometrically (including

the golden section), and recommends these be used by artists to

bring their compositions into proportion.21 In this case Bisttram

did not use one of Hambidge's specified rectangles--he made

up his own because he wanted a very steep angle. In fact the angle

of the diagonal is about 15 degrees. The shape in which he set the

design, however, is one of the shapes that Hambidge recommended--two

side-by-side vertically oriented root-five rectangles. The root-five

rectangle (2.236+) is more than twice as long as it is wide, and

is longer and narrower, for example, than the golden section rectangle

(1.618+), whose length is a little more than one-and-a-half times

its width.

It is instructive to think about Bisttram's drawing with the

central vertical axis drawn in, showing the two vertical side-by-side

root-five rectangles.22 This shows that Bisttram oriented

his design on the page so that the central vertical axis would bisect

the small circle at the top, and form the left edge of the cube,

adding yet another layer of meaning to the image. Bisttram may have

selected the root-five format, as he did in other works, because

of its cosmic dimensions. The diagonal of the root-five rectangle

makes an angle of 23.5 degrees, the angle of the inclination of

the earth's axis to the pole of the ecliptic. Bisttram, following

Hambidge and Plato, defined beauty as "a matter of functional

coordination."

Bisttram's drawing is executed in pencil with an exacting technique

of very small dots, utilizing negative space that leaves the lines

of the drawing white. He executed some 25 drawings in this style

in the late 1930s. I argue in my dissertation that although Bisttram

studied Kandinsky's Point and Line to Plane in the late 1920s

when he was developing his Three-Year Course, a course which he

taught with some variations during the entirety of his teaching

career, he did not become acquainted with Kandinsky's geometrical

abstractions until he saw them reproduced in the Guggenheim catalogues

that were published beginning in 1936. While many of Bisttram's

"transcendental" works are influenced by the works in

these catalogues, I propose that the works belonging to this series

were done independently of visual influence from Kandinsky, and

represent an original aesthetic expression.

Notes>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|