| |

In a journal entry dated the evening of November 19, 1942,

Agnes Pelton contemplated her purpose in painting:

Resting in twilight after reading Dostoyevsky, a quietness,

thinking if I should start a landscape or go on with abstraction,

and feeling poorly, can I do my best with them? . . .still

deeper quiet, and it seemed there was a Presence, shadowy

but Real--and if so, is this He? It seemed so, and this

is my first such intimation--it was an artist presence of

deep, gentle power--remote, but directed toward me. So it

seemed the abstractions must go on, not to stop them ever,

from discouragement.1

|

|

|

In this reflection, Pelton merged the presence of a divinity

with the spirit of the artist, a combination of religion and

art that often found outlet in her painting. Pelton’s self-declared

“life’s work” was to create meaningful abstractions,

her “windows to an inner realm,” “the exploration

of places not yet visited.” Abstractions, for Pelton, were

“a new way of seeing.”2

Meditation, receptivity, study, and divine inspiration created

Pelton’s abstractions. She worked on individual paintings

sporadically for months, sometimes for years. Pelton’s powerful

drive to paint these inner visions also developed over time

and resulted from multiple causes. Pelton’s work in abstraction

began during the first two decades of the 1900s when she lived

in New York City and continued throughout her life. She was

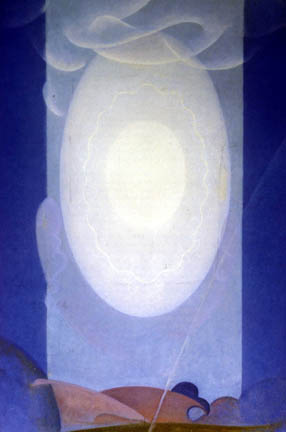

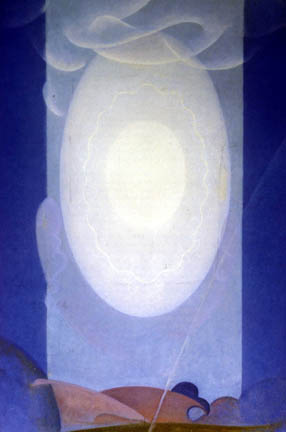

working on her final painting, Light Center (fig. 1), when

she died in 1961, at her home in the desert community of Cathedral

City, California.

In particular, subjects, symbols, and influences suggested

by Pelton’s abstractions can be linked to aspects of her life.

Entwined with the personal and biographical is Pelton’s immersion

in the natural world, the cosmos, mysticism, and the occult.3

Further, the abstractions express reflections about nature,

sexuality, intellect, and creativity. Even more, her works

embody a developing spirituality and make clear her life’s

purpose: to use abstractions to convey her “light message

to the world.”4

A student of Arthur Wesley Dow and Hamilton Easter Field,5

Pelton was already an accomplished painter of representative

figures and landscapes when she exhibited in the Armory Show

in 1913. In the 1910s, Pelton’s imaginative paintings were

similar in style to those of Arthur B. Davies and featured

wispy, young ingénues surrounded by natural landscapes.

Even with her early work, Pelton explored abstract concepts

which she identified in titles, like Supremacy (1915), Power

(1916), Inward Joy (1915), Thought (1916, Peace (1922), and

Vision (1915).6 Throughout her more than sixty

professional years of painting, Pelton continued to complete portraits,

landscapes, and floral scenes to make a living, but she dedicated

her soul to abstraction.

Abstraction became Pelton’s visual representation of a spiritual

quest. She explored multiple ideologies as she developed her

own iconography. Because she believed the Presbyterian and

fundamentalist beliefs of her ancestors were both socially

and personally flawed, Pelton investigated and embraced the

tenets of Agni Yoga,7 Theosophy,8 other Eastern religions

and New Age philosophies. Pelton was also a “sensitive,”9

believed in auras, made personal choices based on numerology,

and explained physical ailments through astrological chartings.

Through the years, she studied the teachings of Annie Besant

and Charles Leadbeater, Krishnamurti, and Shambhala. In her

abstractions, Pelton expressed a strong inner response to life,

including sexuality and creativity. Through her abstractions, she

explored the outer cosmos and her view of an inner world.

Pelton outlined her purpose for painting in a journal entry

entitled “Knowledge.” She copied the following passage from

an unidentified Theosophist: “Spiritual transactions must

be translated into the language of mortal senses that they

be understood, so as to be of practical benefit to mortals

who desire to be redeemed from mortality.” These words articulate

Pelton’s design--to translate spiritual messages with her

paintings. In brackets on that page, she added her own comments:

“This is where the forms of the natural world must appear

in a picture, or can do so--not for themselves but to convey

thought as future light.”10 Thus, light is

a both a symbol and a subject in Pelton’s abstractions. It

represents enlightenment and ecstasy; it also suggests inspiration

and the creative force.

The principles of Theosophy provided a spiritual grounding

for Pelton. In her journal, she often quoted Helena Blavatsky,

but in another journal entry, she referred to L. W. Rogers’

The Elementary Theosophy. In particular, she noted Rogers’

reference to “the ray,” always present in Theosophical teachings.

Pelton copied: “It [the ray] is literally a spark of the divine

fire. . .an emanation of God” that comes to earth and touches

the soul.11 Pelton gave form to this passage in her abstraction,

The Ray, 1931 (fig. 2). In this abstraction, she connects

the earthly world with the shaft of light slanted upward.

The flower, centered at the base of the column of light, symbolizes

human creativity; the light source directs the spirit’s journey

upward.

|

|

|

Pelton was drawn to Theosophy because it emphasized knowledge

and good work. It also afforded her a network of practitioners,

if and when she needed support or encouragement. Generally,

Pelton worked alone in her studio, without frequent contact

with other artists. However, in 1928-29, she associated with

a spiritualist colony called the Glass Hive12 in

Pasadena, California. Leaving her studio in New York City,

Pelton planned to visit her friend Emma Newton in Pasadena

for an extended stay. Newton introduced Pelton to Will Levington

Comfort, the leader of the Glass Hive, and both women became

active with the Hive.

Comfort claimed “not to be a Theosophist, nor cultist of any

kind,” yet his beliefs were based on a variety of works, some

he named specifically, including the Bible, Annie Besant’s

Thought-Power and Blavatsky’s Theosophical treatises. He also

mentioned “straight Hindu literature,” Alfred Pierce Signet’s

Esoteric Buddhism (1894), the Bhagavad Gila, and the words

of Swami Vivekananda.13 Pelton, who had also noted

these works in her journal, shared a bond with the other artists

and writers associated with the Hive. Further, she embraced

Comfort’s philosophy that meditation prepared the way for

an inward journey toward harmony, peace and purpose. During

those months in Pasadena, Pelton’s creativity soared.

|

|

|

The Glass Hive was more than an esoteric group of artists

and writers exchanging ideas. To Comfort, it was an important

link to building a stronger, more civilized world. Membership

in the Hive fluctuated, as connections to the group extended

nationwide; individuals participated at various levels, some

only through the publications, others through association

with those who knew Comfort’s books, letters, and periodicals.

For five years, 1927-32, Comfort edited a small journal, The

Glass Hive, which stated the group’s philosophy and made clear

its connection to the Aquarian Foundation. Articles in The

Glass Hive covered subjects ranging from astrology to the principles

of Agni Yoga, to the cosmos, to communism, to current issues

like the “marriage” question, to the creative process, in

general, and the production of art, in particular. Although

contributors were usually identified only by initials, some

named individuals included Dane Rudhyar,14 whose

book Seed Ideas--Art as a Release of Power was praised, artist

Mabel Alvarez, D.H. Lawrence, Dorothy Brett, Mahatma Gandhi,

artist Beatrice Wood, and artist Thomas Tyrone Comfort, to

name a few.

|

|

|

Association with the Glass Hive extended Pelton’s circle of

acquaintances. During that 1928-1929 trip to Pasadena, for

example, Pelton developed a lasting friendship with Comfort’s

daughter Jane. They exchanged letters for more than twenty-five

years, and discussed topics such as creativity, astronomy,

spirituality, meditation, landscape, painting, writing, health,

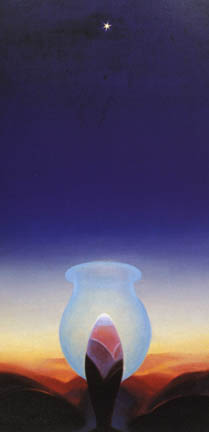

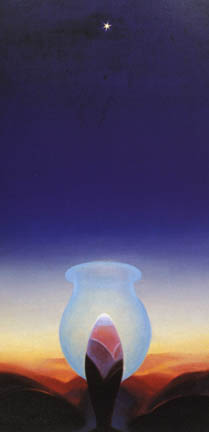

family, and friendship. While part of the Hive in 1929, Pelton

painted and first exhibited Jane’s striking portrait and created

Incarnation, an abstraction she dedicated to Jane Comfort.

Moreover, during her stay in Pasadena Pelton exhibited Ecstasy,

1928 (fig. 3), and did sketches for Star Gazer, 1929 (fig.

4).15

The environment around the Hive encouraged individual, creative

activity. Pelton not only focused on the spiritual quest,

but she also explored the physical world. She may have done

sketches for one of her first desert landscapes, California

Landscape Near Pasadena, dated 1930. At nearby Huntington

Botanical Gardens, she filled her sketchbook with detailed

drawings of flower heads and stems. Based on her dated sketches,

the Huntington Gardens were the probable inspiration for her

painting, Lotus for Lida, 1929 (fig. 5), which can be considered

one of the earliest abstractions painted in California.

While in Pasadena, Pelton exhibited abstractions, floral works,

landscapes, and portraits at the Grace Nicholson Art Galleries

in Pasadena and a select group of abstractions at Jake Zeitlin

Books in Los Angeles. All her activity attracted notice. Reviewers

in the Los Angeles Herald called her paintings “abstractions

externalized on canvas” and touted them as “program music

of the imagination.”16 Pelton was pleased with the

public reception of her abstractions in Los Angeles and enthusiastically

planned an exhibition in New York City at the Montross Gallery

for the following November. A letter to her friend Mabel Dodge

Luhan in Taos, in October 1929, confirmed her expectations:

I am about to start on for me--a real adventure, an exhibition

of my “Abstractions” at the Montross Gallery. . . .If

you think of any of your friends whom you think would be interested,

I would appreciate it if you would send their names for

a catalogue. These pictures are, I am sure, my especial

[sic] light message to the world. They created considerable

interest in California, so I decided it was now or never

in New York, and I want to get those people who might be

interested in them and what they stand for to come and see

them. . . .17

Abstractions were Pelton’s quest for peace in body, mind,

and spirit. Her works exude a timelessness, a journey toward

ecstasy in the natural world or in space beyond.

It is the multivalent concepts of the term “ecstasy” which

lead to the personal in Pelton’s abstractions. Connotations

of ecstasy reach toward physical pleasure, religious understanding,

intellectual enlightenment, and spiritual transcendence. When

she painted her flowering abstraction Ecstasy in 1928 (fig.

3), Pelton entered a cultural debate about the meaning of

the abstract concept of ecstasy. Other artists of the time,

too, explored ecstasy as a subject in abstraction, including

her friend and peer, Raymond Jonson.

|

|

|

Based in the writing and thinking of the time, there is no

question that the term ecstasy implied both a sexual and a

spiritual release. For example, Will Comfort and Mary Austin

were two writers, known by Pelton, who discussed ecstasy in

detail. Comfort, for instance, described the exquisite moment

of physical ecstasy in his biography, Midstream, which Pelton

read soon after its publication in 1914. Comfort said, “The

words from the lips of a woman in the ecstasy of love are

mystical, vibrant from the very source of things. . . .The

man who is not hushed in the presence of it, is not sensitive

to divine presence. . . .She is a love-instrument played upon by

creative light.”18 Comfort mixed the physical with

the divine, but he also linked ecstasy to the creative process

when he stated, “There is an ecstasy in the first view of

one’s unborn realizations.”19

Austin expressed her views about religious and sexual ecstasy

while she was living in New Mexico in 1919. That year, Pelton

spent time with Austin in Taos as part of Mabel Dodge Luhan’s

circle. The women undoubtedly exchanged views on ecstasy,

as it was a topic Austin heatedly debated in a series of letters

written in 1919 to Theodore Schroeder20 of the

School of American Research in Santa Fe. In those letters,

Austin appeared to share the same ideas that Comfort had espoused

when she said, “Sex always stirs the part of women which is

closest in touch with the Law of Life. Sex is the prelude

to the great experience of continuity of life, so that there

is nothing abnormal, nothing that requires a special explanation

in the close association of sex experience and religious experience.”

She added, “Love and religion are like two strings on a musical

instrument. You cannot pluck strongly at one without raising

overtones in the other.”21 Austin disagreed with

Schroeder’s insistence that religion was a debased and perverted

sex experience. For Austin, sex and religion were separate

entities, she said, but she did allow that for other women,

religion often became the outlet for sexual energy.22

However, in another letter, Austin described the ecstatic

states she experienced as intellectual, and religious, noting that

the “result of a subconscious perception of truth” has

a “pale glow of exactly the same thing that accompanies religious

ecstasy.”23 Often, the intellectual, sexual, religious,

and emotional references to ecstasy are merged.

Perhaps it is also the multiple connotations of ecstasy and

release that make Pelton’s Ecstasy, 1928 (fig.3) so intriguing.

Not only does this abstraction represent a natural object,

a flower, which has sexual connotations of alluring beauty

and reproductive forces of its own, but the abstraction also

contains occult references with its “dark hook” of energetic

craving,24 its blossoming release, and its resultant

opening to the light of the sun. In the poem25

Pelton composed to accompany this abstraction, she alludes

to the multiple meanings of ecstasy. Physical growth, emotional

release, and intellectual aspiration or enlightenment are mixed

with the religious suggestion of ascension to a higher joy.26

Clearly, Pelton uses the multiple meanings of “ecstasy” to

bind the material and physical world to the spiritual.

It is in her abstraction, Star Gazer, 1929 (fig. 4), that

the combination of the physical and spiritual worlds merge

most graphically. Primary colors and a upward, visual trajectory

toward the star dominate in this abstraction. The bottom third

of the painting contains earth-like images in reds and yellows;

the remaining portion consists of a sky in deepening shades

of cobalt blue, with one bright, six-pointed orb. At first

glance, the most prominent image is a pale green vase on a

pedestal of maroons and pink, centered at the bottom of the

canvas, surrounded by a rolling mass of hills of dark black-brown,

reds, and pale orange. Contained within the vase is a scaled projectile-shaped

object, pointed upward. A yellow glow covers the horizon and

lights the lower portion of the sky. Pelton’s arrangement

of colors, befitting of landscape, earth and sky, has additional

occult significance that appeals, perhaps, on the intuitive

level to viewers who are aware of the body’s color-coded chakras.27

In Star Gazer, Pelton abstracts both the human figure and

the plant to create a sense of growth, a new beginning, another

dawn.28 This abstraction projects multiple images

of creativity. Primarily, the central object is a plant sprouting

from the soil, growing toward the light. However, the projectile

within the vase might represent the sexual act, perhaps a

referent to a penis penetrating a womb. The landscape would

then become a body and the united act aimed toward the star,

a dual image of ecstasy, physical and spiritual. In a similar

mixture of images, the star shining in the sky could be the

North Star, the traveler’s compass, or the Star of Bethlehem.

It might signify an idea, a heavenly blessing, or a divine presence.

Or, it could simply refer to Venus, the morning star, as Pelton

noted in her journal. As the eye of the night, it could signify

spiritual enlightenment and wisdom, as well as human aspiration.29

Star Gazer becomes more complex when the sexual interpretation

moves through other levels. In this abstraction, there is a creative

spirit, a sprouting plant, a growth within the universal womb,

above the plane of the earth. In Star Gazer, the physical

and spiritual ecstasy blend as the destination is the star,

a guiding light.

Pelton’s compulsion to paint abstractions that conveyed her

spiritual aspiration evolved in the 1920s and continued until

her death. A selected series of her paintings illumine patterns

of images she developed. Examining the religious underpinnings

in these examples establish Pelton’s abstractions as personal

statements with a universal purpose--to bring light to life.

In these abstractions with a spiritual motif, Pelton created

on canvas an upward movement through space. This sense of

trajectus sursum30 is spiritual and physical, earthly

and cosmic, real and hopeful. It is the visible reflection

of her inner goal, the sharing of which became her purpose.

Taken as a series, the abstractions--Star Gazer, The Guide, Illumination,

Alchemy, Awakening, Voyaging, and Light Center--illumine the

soul’s journey as seen through Pelton’s painted symbols.

As an overall statement of Pelton’s spiritual vision, these

abstractions illumine a structured progression, regardless

of their chronological completion. Like pieces of the puzzle

assembled in different moments of reflection, meditation,

and inspiration, these abstractions are Pelton’s vision of

immortality given painted form.

In Pelton’s design for the spiritual journey, a questioning

exists, at first, a longing for explanation, a gesture toward

the heavens, a need for response. Star Gazer represents that

possibility. Then, mentors, philosophies, and opportunities

are provided to spark the individual’s desire to know. At

this point in the quest, the individual looks to The Guide

for direction, discovering that the true source of power,

light, and awareness might exist within the mind. Suddenly,

the spiritual quest, which was once a vague, unformed longing,

becomes a way of life, as evidenced in Illumination. A mystical

change occurs as the material of the body and physical world

becomes the spiritual in Alchemy. With this, the soul has

a rebirth, an Awakening, and begins its final, upward journey. In

Voyaging the golden bell rings, a signal that an individual’s

life on earth has prepared the way of the future. In Light Center,

the ultimate realization is simple: the true center of radiance

comes from within. What matters is allowing the spirit to

glow outwardly through its human form, sharing the light with

others. In these abstractions and others, Pelton offers a

visual mapping of the path toward enlightenment and spiritual

ecstasy.

About her last painting, Light Center, (fig. 1) Pelton said,

“Life is really all light, you know.” In this abstraction,

from its intensely luminous center disk, a white oval radiates

outward through the wavy, lighted “aura” to its hazy, glowing

edges. The top of the oval brushes the cloud forms above as

it hovers, suspended in mid-air, over the earth-tone masses

below. A powerful shaft of light cuts through the blue sky

background, covering the middle, vertical third of the canvas.

This connecting ray of light illuminates the cloud edges,

encompasses the white oval, and disappears into the ground

below. Faint purple plumes, like hands, seem to provide a

floating resting space for the central oval of light. This painting

does not have a separate star. The light source is the oval and

the circle within.

Pelton’s concept in this abstraction parallels a passage from

Dane Rudhyar’s Art as a Release of Power in his series entitled

Seed Ideas. Rudyhar believed every “organized entity. . .has

a life-center, the heart and soul of the entity. To this center

comes impressions from the outer world. . .from this center

radiate impulses which cause various types of motion, affecting

in some ways the outer world surrounding the boundaries of

the organism.” In other words, Rudhyar’s entity is the center

of all impulses, incoming and outgoing, “an evolving self,”

the “All Form, the one Universal Self” which exists in the

“Eternal Now.” At this ultimate point, time and space do not

exist, and the individual Light Center becomes part of the

Universal Soul.31

By replacing the external guiding light, or star, with a white

flame or radiance emerging from a light source within the

self, Pelton confirmed the individual’s powerful role--to

bring light to life. Obviously, in Pelton’s view, “seeing

the light” was her spiritual goal, the sunlight her inspiration,

a star her guiding light, and enlightenment--or spiritual

ecstasy--became her work in the world.

Notes>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|