| |

|

|

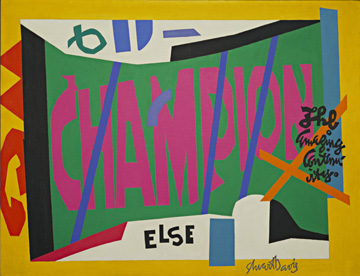

Fig 1: Lucky Strike,

1921

|

What was Stuart Davis' response

to and opinion of modern American popular culture? The existing

scholarship on Davis, being mostly formalist criticism, hardly says.

Davis has entered the canon of American modernism because of his

talent for pictorial composition and mastery of European modernist

styles which he brilliantly Americanized.This basis for his canonical

status fails to account for Davis'exploration through painting and

drawing of modern American life as manifest in everyday household

objects and the mass-produced imagery of advertising, package design,

and the media. It is possible, by utilizing twentieth-century

cultural theory, to discern Davis' attitude toward the commodity

capitalism that fueled enormous prosperity in the United States

during his lifetime and which appear often in his oeuvre.

Davis was able

to think of painting in terms of formal and non-formal content simultaneously,

a fact which the mostly formalist approaches to him has obscured.

In his 1935 essay "Abstract Painting in America," Davis wrote that

a painting is "a two-dimensional plane surface and the process

of making a painting is the act of defining two-dimensional space

on that surface."1 He was very concerned with

visually satisfying and engaging forms, colors, and compositions,

but he never distanced his art from non-formal expression; quite

to the contrary, he wholeheartedly embraced social and ideological

content in his art. Davis became an artist under the influence

of Robert Henri and the Ash Can School, and the sociological perspective

of this modern urban realism stayed with him his entire life.

In the 1930s, Davis was active in Marxist politicsBhe read Marx,

Lenin, and related political thinkersand was a supporter of the

poor and the working classes in their struggle to improve their

lives during the Great Depression.2

Davis

considered art to have a vital role in society, as he explained

in great detail in his 1940 essay Abstract Painting Today:

The sociological theorist says that art is a social expression

and changes as society changes, and so it does.... . [The sociological

theory of art] conceives [of] art as a social function changed

and molded by the social forces in its environment merely in a

passive way.... . This viewpoint fails to see that the work

of art itself changes the emotions and ideas of people.3

He wrote in Abstract Art in the American

Scene that modern art has not changed the social function of

art but has kept it alive by using as its subject matter the new

and interesting relationships of form and color which are everywhere

apparent in our environment."4 Davis believed art

could change people's lives, that it could affect the emotions and

thinking of people, that it reflected social changes but could also

produce them.Davis believed modern art in general, and of course

his art in particular, was inextricably related in style and subject

to modern life, particularly in the tangible manifestations of modernity

such as the wide variety of industrially mass-produced commodities

that transformed everyday life and made possible many new experienceslights,

sounds, spaces, and speedsthat were all quintessentially modern

and American. Davis discussed the closeness between modern

art and modern life often in his essays. His thoughts are

close in spirit, more than in style, to the ideas on modern technology

and how it should manifest itself in modern art espoused by the

Cubist Fernand Leger and the Futurists. Davis wrote in "The

Cube Root" that "modern pictures deal with contemporary subject

matter in terms of art. The artist does not exercise his freedom

in a non-material world. Science has created a new environment,

in which new forms, lights, speeds and spaces, are a reality."5

In Is There a Revolution in the Arts he wrote that "we

[modern artists] prefer the modern works because they are closer

to our daily experience. They were painted by men who lived, and

who still live, in the revolutionary lights, speeds, and spaces

of today, which science and art have made possible."6

Leger and the Futurists were excited by the advances in technology

and industry that they had witnessed or anticipated in the early

twentieth century.7 They believed everyday life

would be easier and more enjoyable because these technological developments

would filter into industry, commerce, and private life. The

exalting attitude toward modern technology of the Futurists is clearly

declared in "The Manifesto of the Futurist Painters," a joint

effort of 1910 by Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carra, Luigi Russolo,

Giacomo Balla and Giacomo Severini, when they wrote:

We tell you

now that the triumphant progress of science makes profound changes

in humanity inevitable....we are confident in the radiant splendour

of our future.... . Living art draws its life from the surrounding

environment...we must breathe in the tangible miracles of contemporary

art--the iron network of speedy communications which envelop the

earth, the transatlantic liners....those marvelous flights which

furrow our skies.... . How can we remain insensible to the

frenetic life of our great cities and to the exciting new psychology

of night life.... .8

Davis offered

an explanation of the relationship between modern art and modern

technology in Is There a Revolution in the Arts that essentially

summarizes the ideas of Leger and the various Futurists in declaring

that modern art is largely an impassioned response to everyday life

and that the relationship between modern art and life is so fluid

that the two are inseparable. He wrote that:

an artist

who has traveled on a steam train, driven an automobile, or flown

in an airplane doesn't feel the same way about form and space

as one who has not. An artist who has used a telegraph,

telephone, and radio doesn't feel the same way about time and

space as one who has not. And an artist who lives in a world

of the motion picture, electricity, and synthetic chemistry doesn't

feel the same way about light and color as one who has not.

An artist who has lived in a democratic society has a different

view of what a human being really is than one who has not.

These new experiences, emotions, and ideas are reflected in modern

art.... .9

In "The Cube

Root" Davis enumerated some of the tangible, visible aspects of

everyday modern life which inspired his own work:

Some of

the things which have made me want to paint, outside of art, are:

American wood and iron work of the past; Civil War and skyscraper

architecture; the brilliant colors on gasoline stations; chain-store

fronts; and taxi-cabs; the music of Bach; synthetic chemistry;

the poetry of Rimbeau; fast travel by train, auto, and aeroplane

[sic] which brought new and multiple perspectives; electric signs,

the landscape and boats of Gloucester, Massachusetts; five and

ten cent store kitchen utensils; movies and radio; Earl Hines

hot piano and negro jazz music in general, etc. In one way

or another, the quality of these things plays a role in determining

the character of my paintings. Not in the sense of describing

them in graphic images, but by predetermining an analogous dynamics

in the design, which becomes a new part of the American environment....just

Color-Space Compositions [sic] celebrating the resolution of stresses

set up by some aspects of the American scene.10

In "Modernism

and Mass Culture in the Visual Arts," his groundbreaking essay of

1981, Thomas Crow writes that avant-garde art has repeatedly been

inspired, influenced, and renewed by mass culture and everyday life.

Crow reminds us of the many instances in which modern art borrows

certain visual forms or aspects of content from mass culture, sometimes

in very profound ways and other times in very subtle ways, beginning

in Cubist collages and continuing through Dada and Constructivism,

even affecting such purist abstraction as the late work of Mondrian,

and becoming the central element in Pop and much postmodern art.

Crow thinks the issue of quality remains the exclusive domain of

high art, an opinion Davis might have held, but he believes that

modern (high) art is greatly influenced and conditioned by mass

culture, that mass culture is "prior and determining, modernism

is its effect" in that "mass culture has determined the form high

culture must assume."11It is in perceiving mass culture

as the source and inspiration for avant-garde, modern art that Crow

and Davis so obviously agree. Davis' closeness to Crow's thinking

is clearly indicated in his enumeration of his inspirations outside

of art in "The Cube Root." Davis does not seem to have been preoccupied

with distinctions between high and low in art, although he was surely

aware of them.Davis was not totally uncritical of mass culture and

capitalism. In "What About Modern Art and Democracy?,"

Davis criticized capitalism for its tendency to manipulate the public

in its search for huge profits. In this article, Davis wrote

that capitalists use their wealth and influence to glorify the representational

art that depicts distinctly American subjects (the people, landscapes,

and buildings of the United States) in ways which emphasize their

American identity and values in order to exploit a reactionary,

provincial perspective of life that serves their hunger for profits.

He placed some of the blame for this exploitation on the public

itself, which he considers eager for advances in industrial commodities

but in favor of old-fashioned values in art and culture. Davis

wrote:

Business puts

its weight behind glorifying an art, supposedly founded on sound

American traditions, which exploits the American scene in terms

of traditional and provincial ideology.... . The familiar,

the literal, or the "folksy" is reiterated to the exclusion of

new vision and new synthesis. The public....seems to want

its artists' vision in traditional forms. Creative bathrooms

and kitchens are eagerly desired, and we are told that it will

soon be possible to bring home the dehydrated soup from the A

& P in a helicopter; but in cultural matters, nostalgia for

the old frontiers tends to dim out the new frontiers already in

view.... . Business approves of art, yes, but an art of

the status quo to soothe the public mind and keep it on the beam....

.12

Lucky Strike

of 1921 [Fig. 1] features an array of fragmented motifs abstracted

from the packaging for that cigarette brand which have been juxtaposed

in bold, contrasting patterns. This painting captures the

effect of abrupt opposition and deformation found in Cubist collage,

but does so artificially, since it is entirely executed in oil.

The arrangement of forms loosely simulates what a cigarette

package would look like if dismantled and flattened.13

Davis seems to be using Cubism to analyze the visual logic and psychological

effects of commercial packaging. Lucky Strike engages

Crows claim that mass culture and high art are on parallel paths

in the search for greater understanding of life, except that the

relationship between mass culture and art in Davis painting is not

parallel: mass culture is drawn into art in the search for understanding.

Davis' works should not be taken as slavish, uncritical acceptance

or celebration of mass-media imagery and industrially-produced goods,

as they often are. In fact, skepticism may be imbued in many

of Davis' works. Perhaps the abrupt, confusing arrangement

of fragmented forms refers to the artificiality and deception of

clever package design and advertising, which is directed at consumers

and is intended to lure them into desiring and then purchasing an

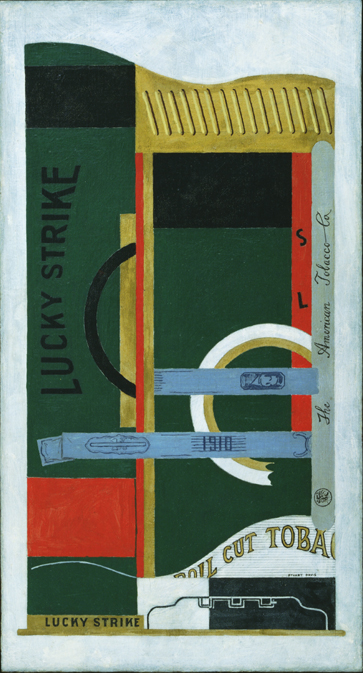

item. Davis admitted in his essay on his 1951 painting Visa

[Fig. 2] that the painting was inspired by an advertisement in a

matchbook cover which he found boring and hoped to make interesting

in his series of paintings based on it. As with his paintings

of commercial products from the 1920s, Visa and the other

"Champion" paintings were initiated by contact with mass culture.

He said his use of the word "else," as in "something else" or "somewhere

else," indicated his belief that all subject matter was equivalent,

but that even though certain words would automatically convey specific

meanings, he chose to avoid conveying them, being more concerned

with formal issues.14 However, considering the

continuity of Davis' theories, it is difficult to believe that "else"

is without any meanings other than purely formal effects.

Instead, the vagueness of "else" may refer to the monotony and simplicity

of mass-media imagery, that one image inspired by mass-media imagery

but then reconceptualized by the modern artist is nothing more or

less than something "else".

|

|

Fig

2: Visa, 1951

|

Visa has the qualities of heavy-handed

and superficial excitement and pleasure, of easy and fleeting experience,

and intellectual banality for which mass culture has been derided

by many leading critics and theorists of modern art and culture,

including Clement Greenberg in "Avant-Garde and Kitsch" and Max

Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno in "Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction."

It achieves what Davis called "analogous dynamics," a quality he

sought in his art in order to give form to his response to mass

culture. The repetition of the basic composition in several

paintings, each one differing mostly in its color scheme, alludes

to the redundancy of mass culture about which many theorists have

been quite vociferous. This redundancy undermines the qualities

of originality and authenticity associated with works of art, qualities

Walter Benjamin described as the "aura" of the work of art.

Benjamin saw the aura of the work of art diminished by photography,

film, and advances in printing, which proliferated imagery during

the twentieth century. In the "Champion" series, the aura

of the work of art is diminished not by mechanical methods of visualization

and reproduction, but by the artist's repetition of the composition.

If Visa has the "analogous dynamics" of mass culture,

what if anything separates it and its sister paintings from mass

culture itself? What makes it "art?" Davis'

announced intention to make the found advertisement more interesting

has involved stripping the advertisement of its ease of comprehension,

thereby making it less effective in communicating commodity identity,

utility, and attractiveness. What makes this high art and a great

modern painting is the opposite of what made it effective commercial

packaging and popular culture.

Notes>>

Author's

Bio>>

|

|