| Stuart Davis' Taste for Modern American Popular Culture by Herbert R. Hartel, Jr. The following is a revised version of the original article. The revised version was posted online on Friday, April 25, 2008.

|

|

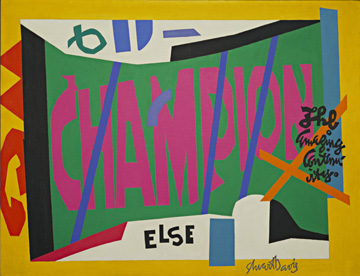

| Fig 1: Stuart Davis,

Lucky Strike, 1921, oil on canvas, 33_ x 18", Museum

of Modern Art, New York |

What was Stuart Davis’ response to and opinion of modern American popular culture? The existing scholarship on Davis, being mostly formalist criticism, hardly says. Davis has entered the canon of American modernism because of his talent for pictorial composition and mastery of European modernist styles which he brilliantly “Americanized.” This basis for his canonical status fails to account for Davis’ exploration through painting and drawing of modern American life as manifest in everyday household objects and the mass-produced imagery of advertising, package design, and the media. It is possible, by utilizing twentieth-century cultural theory, to discern Davis’ attitude toward the commodity capitalism that fueled enormous prosperity in the United States during Davis’ lifetime and which appear often in his oeuvre.

Davis was able to think of painting in terms of formal and non-formal content simultaneously, a fact which the mostly formalist approaches to him has obscured. In his 1935 essay “Abstract Painting in America,” Davis wrote that a painting is “a two-dimensional plane surface and the process of making a painting is the act of defining two-dimensional space on that surface.”[1] He was very concerned with visually satisfying and engaging forms, colors, and compositions, but he never distanced his art from non-formal expression; quite to the contrary, he wholeheartedly embraced psychological, social, and ideological content in his art. Davis became an artist under the influence of Robert Henri and the Ash Can School, and the sociological perspective of this modern urban realism stayed with him his entire life. In the 1930s, Davis was active in Marxist politics–he read Marx, Lenin, and related political thinkers–and was a supporter of the poor and the working classes in their struggle to improve their lives during the Great Depression.[2]

Davis considered art to have a vital role in society, as he explained in great detail in his 1940 essay “Abstract Painting Today”: “The sociological theorist says that art is a social expression and changes as society changes, and so it does...[The sociological theory of art] conceives [of] art as a social function changed and molded by the social forces in its environment merely in a passive way... This viewpoint fails to see that the work of art itself changes the emotions and ideas of people.”[3] He wrote in “Abstract Art in the American Scene” that “modern art has not changed the social function of art but has kept it alive by using as its subject matter the new and interesting relationships of form and color which are everywhere apparent in our environment.”[4] Davis believed art could change people’s lives, that it could affect the emotions and thinking of people, that it reflected social changes but could also produce them.

Davis believed modern art in general, and of course his art in particular, was inextricably related in style and subject to modern life, particularly to the tangible manifestations of modernity such as the wide variety of industrially mass-produced commodities that transformed everyday life and made possible many new experiences–lights, sounds, spaces, and speeds–that were all quintessentially modern and American. Davis discussed the closeness between modern art and modern life often in his essays. His thoughts are close in spirit, more than in style, to the ideas on modern technology and how it should manifest itself in modern art espoused by the Cubist Fernand Léger and the Futurists. Davis wrote in “The Cube Root” that “modern pictures deal with contemporary subject matter in terms of art. The artist does not exercise his freedom in a non-material world. Science has created a new environment, in which new forms, lights, speeds and spaces, are a reality.”[5] In “Is There a Revolution in the Arts?” he wrote that “we [modern artists] prefer the modern works because they are closer to our daily experience. They were painted by men who lived, and who still live, in the revolutionary lights, speeds, and spaces of today, which science and art have made possible.”[6] Léger and the Futurists were excited by the advances in technology and industry that they had witnessed or anticipated in the early twentieth century.[7] They believed everyday life would be easier and more enjoyable because these technological developments would filter into industry, commerce, and private life. The exalting attitude toward modern technology of the Futurists is clearly declared in “The Manifesto of the Futurist Painters,” a joint effort of 1910 by Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carra, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla and Giacomo Severini, when they wrote:

We tell you now that the triumphant progress of science makes profound changes in humanity inevitable...we are confident in the radiant splendour of our future... Living art draws its life from the surrounding environment...we must breathe in the tangible miracles of contemporary art–the iron network of speedy communications which envelop the earth, the transatlantic liners...those marvelous flights which furrow our skies... How can we remain insensible to the frenetic life of our great cities and to the exciting new psychology of night life...[8]

Davis offered an explanation of the relationship between modern art and modern technology in “Is There a Revolution in the Arts?” that essentially summarizes the ideas of Léger and the Futurists in declaring that modern art is largely an impassioned response to everyday life and that the relationship between modern art and life is so fluid that the two are inseparable. He wrote that:

an artist who has traveled on a steam train, driven an automobile, or flown in an airplane doesn’t feel the same way about form and space as one who has not. An artist who has used a telegraph, telephone, and radio doesn’t feel the same way about time and space as one who has not. And an artist who lives in a world of the motion picture, electricity, and synthetic chemistry doesn’t feel the same way about light and color as one who has not. An artist who has lived in a democratic society has a different view of what a human being really is than one who has not. These new experiences, emotions, and ideas are reflected in modern art...[9]

In “The Cube Root” Davis enumerated some of the tangible, visible aspects of everyday modern life which have inspired his own work:

Some of the things which have made me want to paint, outside of art, are: American wood and iron work of the past; Civil War and skyscraper architecture; the brilliant colors on gasoline stations; chain-store fronts; and taxi-cabs; the music of Bach; synthetic chemistry; the poetry of Rimbeau; fast travel by train, auto, and aeroplane [sic] which brought new and multiple perspectives; electric signs, the landscape and boats of Gloucester, Massachusetts; five and ten cent store kitchen utensils; movies and radio; Earl Hines hot piano and negro jazz music in general, etc. In one way or another, the quality of these things plays a role in determining the character of my paintings. Not in the sense of describing them in graphic images, but by predetermining an analogous dynamics in the design, which becomes a new part of the American environment...just Color-Space Compositions [sic] celebrating the resolution of stresses set up by some aspects of the American scene.[10]

In “Modernism and Mass Culture in the Visual Arts,” his groundbreaking essay of 1981, Thomas Crow writes that avant-garde art has repeatedly been inspired, influenced, and renewed by mass culture and everyday life. Crow reminds us of the many instances in which modern art borrows certain visual forms or aspects of content from mass culture, sometimes in very profound ways and other times in very subtle ways, beginning in Cubist collages and continuing through Dada and Constructivism, even affecting such purist abstraction as the late work of Mondrian, and becoming the central element in Pop and much postmodern art. Crow thinks the issue of quality remains the exclusive domain of high art, an opinion Davis might have held, but he believes that modern “high” art is greatly influenced and conditioned by mass culture, that mass culture is “prior and determining, modernism is its effect” in that “mass culture has determined the form high culture must assume.”[11] It is in perceiving mass culture as the source and inspiration for avant-garde, modern art that Crow and Davis so obviously agree. Davis’ closeness to Crow’s thinking is clearly indicated in his enumeration of his inspirations outside of art in “The Cube Root.” Davis does not seem to have been preoccupied with distinctions between high and low in art, although he was surely aware of them.

Davis was not totally uncritical of mass culture and capitalism. In “What About Modern Art and Democracy?,” Davis criticized capitalism for its tendency to manipulate the public in its search for huge profits. In this article, Davis wrote that capitalists use their wealth and influence to glorify the representational art that depicts distinctly American subjects (the people, landscapes, and buildings of the United States) in ways which emphasize their American identity and values in order to exploit a reactionary, provincial perspective of life that serves their hunger for profits. He placed some of the blame for this exploitation on the public itself, which he considers eager for advances in industrial commodities but in favor of old-fashioned values in art and culture. Davis wrote:

Business puts its weight behind glorifying an art, supposedly founded on sound American traditions, which exploits the American scene in terms of traditional and provincial ideology...The familiar, the literal, or the “folksy” is reiterated to the exclusion of new vision and new synthesis. The public...seems to want its artists’ vision in traditional forms. Creative bathrooms and kitchens are eagerly desired, and we are told that it will soon be possible to bring home the dehydrated soup from the A & P in a helicopter; but in cultural matters, nostalgia for the old frontiers tends to dim out the new frontiers already in view...Business approves of art, yes, but an art of the status quo to soothe the public mind and keep it on the beam...[12]

Lucky Strike of 1921 [Plate 1] features an array of fragmented motifs abstracted from the packaging for that cigarette brand which have been juxtaposed in bold, contrasting patterns. This painting captures the effect of abrupt opposition and deformation found in Cubist collage, but does so artificially, since it is entirely done in oil. The arrangement of forms loosely simulates what a cigarette package would look like if dismantled and flattened.[13] Davis seems to be using Cubism to analyze the visual logic and psychological effects of commercial packaging. Lucky Strike engages Crow’s claim that mass culture and art are on parallel paths in the search for greater understanding of life, except that the relationship between mass culture and art in Davis’ painting is not parallel: mass culture is drawn into art in the search for understanding. Davis’ works should not be taken as slavish, uncritical acceptance or celebration of mass-media imagery and industrially-produced goods, as they often are. In fact, skepticism may be imbued in many of Davis’ works. Perhaps the abrupt, confusing arrangement of fragmented forms refers to the artificiality and deception of clever package design and advertising, which is directed at consumers and is intended to lure them into desiring and then purchasing an item.

|

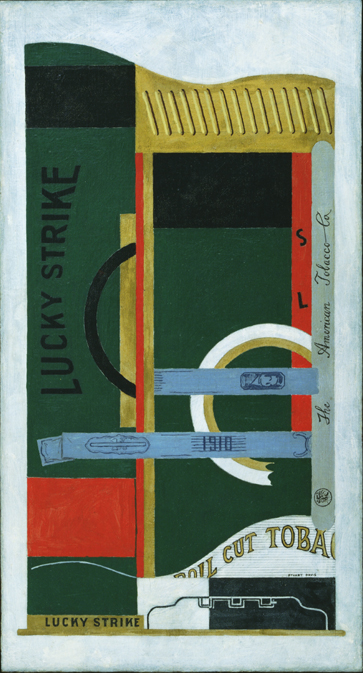

| Fig

2: Davis, Visa, 1951, oil on canvas, 40 x 52",

Museum of Modern Art, New York |

Davis admitted in his essay on his 1951 painting Visa [Plate 2] that the painting was inspired by an advertisement in a matchbook cover which he found boring and hoped to make interesting in his series of paintings based on it. As with his paintings of commercial products from the 1920s, Visa and the other “Champion” paintings were initiated by contact with mass culture. He said his use of the word “else,” as in “something else” or “somewhere else,” indicated his belief that all subject matter was equivalent, but that even though certain words would automatically convey specific meanings, he chose to avoid conveying them, being more concerned with formal issues.[14] However, considering the continuity of Davis’ theories, it is difficult to believe that “else” is without any meanings other than purely formal effects. Instead, the vagueness of “else” may refer to the monotony and simplicity of mass-media imagery, that one image inspired by mass-media imagery but then reconceptualized by the modern artist is nothing more or less than something “else.” Thus, Visa and the other “Champion” paintings may be a comment on the mundane, redundant, banal quality of much mass-media imagery.

Visa has the qualities of heavy-handed and superficial excitement and pleasure, of easy and fleeting experience, and intellectual banality for which mass culture has been derided by many leading critics and theorists of modern art and culture, including Clement Greenberg in “Avant-Garde and Kitsch” and Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno in “Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” It achieves what Davis called “analogous dynamics,” a quality he sought in his art in order to give form to his response to mass culture. The repetition of the basic composition in several paintings, each one differing mostly in its color scheme, alludes to the redundancy of mass culture about which many theorists have been quite vociferous. This redundancy undermines the qualities of originality, authenticity, and singularity associated with works of art, qualities Walter Benjamin described as the “aura” of the work of art. Benjamin saw the aura of the work of art diminished by photography, film, and advances in printing, which proliferated during the twentieth century. In the “Champion” series, the aura of the work of art is diminished not by mechanical methods of visualization and reproduction, but by the artist’s repetition of the composition. If Visa has the “analogous dynamics” of mass culture, what if anything separates it and its sister paintings from mass culture itself? What makes it “art?” Davis’ announced intention to make the found advertisement more interesting has involved stripping the advertisement of its ease of comprehension, thereby making it less effective in communicating commodity identity, utility, and attractiveness. What makes this “high” art is the opposite of what made it effective commercial packaging and popular culture.