Refracting history: Ives and Emerson and the Nineteenth-Century European Tradition in America

|

|||||||

In an 1837 address to the Phi Beta Kappa Society in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Ralph Waldo Emerson prophesied the coming of “The American Scholar.” “We have listened too long to the courtly muses of Europe,”1 he wrote, in his call for a distinctive voice to issue forth from America. Despite the clarity of Emerson’s call, he himself was extremely conscious of European thinking, frequently borrowing images from European models in his writing. He was hardly able to keep himself from reflecting European intellectual history from his position in a place that was still trying to define itself as a nation, let alone as one possessing a cultural identity. It is perhaps more accurate to suggest, however, that Emerson refracted European thinking: he opened it up to new possibilities of understanding.

EMERSON AND HISTORY

These lines are taken from the opening of the first essay of the

First Series of Emerson’s essays, “History,” first

published in 1841. In it, Emerson proposes an entirely organic understanding

of human being and, by extension, of human history. Emerson’s

model for this view is found in his understanding of the behavior

of the natural world: Emerson hardly invented such a notion, which in its vision of an overarching unity guiding a diverse world evokes Plato, and in its employment of metaphors describing such part-to-whole relations in terms of botanical growth recalls Johann Wolfgang Goethe’s notion of the Urpflänze, the “primal plant” from which Goethe hypothesized all other plant forms could be derived.4 Indeed, Goethe extended this notion to a range of natural phenomena, positing an array of Urphänomene. According to Goethe, the full range of discrete objects observed in nature, in all their diversity, could be related back to such Urphänomene. Furthermore, each natural object could be shown to demonstrate its own internal coherence—in the case of the plant, for example, such that each part can be viewed in terms of a transformation or metamorphosis through the leaf-form—which is ultimately reflective of the order of the universe as a whole. Goethe is the subject of the last of Emerson’s collection of essays entitled Representative Men.5 “Goethe; or, the Writer” is a substantial record of the influence of Goethe on Emerson’s thinking. By casting Goethe as “the writer,” Emerson suggests something of his direct kinship with this figure. It would serve neither Emerson nor Goethe, it seems, to be described as merely a philosopher, a mystic, a skeptic, a poet, or a man of the world, the monikers he uses for his other “representative men”. The function of a writer—through whose eyes “a man is the faculty of reporting, and the universe is the possibility of being reported”—seems to be more encompassing. It suggests the function of what we might call a historian, “who see[s] connection where the multitude see fragments, and who are impelled to exhibit the facts in order, and so to supply the axis on which the frame of things turns.”6 This person who is able to make connections among fragments, who can construct a narrative from an array of facts, is in fact engaged in the process of writing history. Emerson and Goethe emerge here as writer-historians of a similar stripe not only by virtue of the breadth of their concerns but by their concern with nature in particular. In what might be viewed as a circular relation to the evocation of Goethe’s organic model that opens “History,” Emerson opens “Goethe; or, the Writer” by declaring his understanding of history through nature: “Nature will be reported. All things are engaged in writing their history.”7 The influence of Goethe on Emerson, who wrote that Goethe “has said the best things about nature that ever were said,” is clear.8 Emerson, however, does not simply mirror Goethe. Emerson and Goethe are not only separated by time, but by considerable physical space. This distance must be calculated not only in terms of miles, but in terms of culture and language; furthermore, the distance must be appreciated in terms of the “nature” to which each of them is responding. Goethe’s inspiration for the Urpflänze occurred during his travels in Italy, which began in 1786. Confronted by a bewildering array of unfamiliar vegetation in Italy, Goethe was led to make detailed notes and drawings documenting his observations. The Urpflänze occurred to him in a flash of intuition during his meditation upon these observations. I would like to suggest that while Goethe’s trip to Italy was no doubt eye-opening, exposing him to varieties of plants that he had never seen before, he was essentially crossing from one civilized European country to another; his adventure was most closely akin to a holiday. The difference between Goethe’s excursion and the American experience lies in the circumstances surrounding the early American settlers’ crossing of the Atlantic Ocean; in the passage from an essentially civilized environment to a truly alien and dangerous wilderness.9 Emerson was writing well into the process of the conquest of that wilderness and its indigenous peoples, but vestiges of that encounter with a variety of nature quite unlike the tame European landscape—and with human beings quite unlike other Europeans—manifest themselves in Emerson’s thorny syntax. Emerson’s relation to nature resonates not merely in terms of Goethe’s profound curiosity, his serious contemplation of natural phenomena, but as a matter of considerable urgency. For Emerson’s immediate American ancestors, learning to understand, describe, and move about in the natural environment was a matter of life and death; this encounter with the wilderness is our history. European models of thinking necessarily resonate differently when they are imported to America. Furthermore, in a place without an established intellectual or cultural tradition, one finds fertile ground for the reinterpretation of European thinking, and its refraction into a range of meanings. This is suggested in the multiplicity of views that Emerson embraces in “History”. “A man is the whole encyclopedia of facts,” he wrote. “If the whole of history is in one man, it is all to be explained from individual experience. There is a relation between the hours of our life and the centuries of time.” 10 An extension of the application of the part-to-whole relationships that so captured Goethe’s imagination, this view that the history of the world is played out microcosmically in each individual lifetime is perhaps possible only in a country founded on principles of individual liberty, principles designed to recognize the intrinsic value of each person, while at the same time recognizing the importance of their contributions to the larger social body. Emerson’s view of history, then, becomes a radically subjective one. He imagines that each of us has our own dialogic relation with history, thus rejecting a static sense of its past-ness and seeking instead to reanimate it in each individual’s present: When a thought of Plato becomes a thought to me,--when a truth that fired the soul of Pindar fires mine, time is no more. When I feel that we two meet in a perception, that our two souls are tinged with the same hue, and do, as it were, run into one, why should I measure degrees of latitude, why should I count Egyptian years? 11 In this way, Emerson can be said to presage the ideal of Hans-Georg Gadamer’s Horizontverschmelzung, in which the horizon of the historical object and the horizon of the observer of the historical object fuse into a relation of understanding.12 In such a state, “History no longer shall be a dull book. It shall walk incarnate in every just and wise man.”13 IVES AND HISTORY Much as Emerson engaged the ideas of his precursor, Goethe, so did Ives engage those of the German musical master Ludwig van Beethoven. This is made clear in Ives’s writings and also in his music. Geoffrey Block notes that Ives “borrowed” musical material from Beethoven more often than he did from any other classical composer. 15 The engagement with Beethoven is especially evident in the Concord Sonata, which is, in essence, a sixty-minute trope on the familiar four-note motive (“bum-bum-bum-BUM”) that opens Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (hereafter, “the Beethoven motive”).

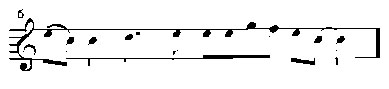

Something of the organic understanding of history expressed in Emerson, by way of Goethe, is articulated in the growth of organic musical structures in Ives’s music, by way of Beethoven. Rather like Emerson’s writer-historian, who is able to make connections among fragments, Ives composed music through a process that J. Peter Burkholder has called “cumulative form”.16 This process, which has much in common with the “organic” growth of themes in Beethoven from small musical “cells,”17 is a variation on standard sonata form. Sonata form typically describes a single movement of a work, in which themes are stated in an “exposition” section, then disassembled and reworked in a “development” section, then restated in their reconstituted form in a “recapitulation” section. In “cumulative form”, Ives begins with fragmentary motives in a process of development and moves toward the clear articulation of a main theme. In the Concord Sonata, this process is expanded to unfold over multiple movements, such that the entire sonata becomes the dramatization of a single theme. Ives called this theme, shown in Figure 1, the “human faith melody”.18 This melody is not heard clearly and completely until the third movement of the sonata, “The Alcotts”, although it appears in fragmented form, buried within the dense textures of “Emerson” and “Hawthorne”. The theme returns as a kind of echo in “Thoreau”, played by a solo flute, wafting out over an imagined Walden Pond. It is important to notice that the Beethoven motive is embedded within Ives’s “human faith melody.” By growing the Beethoven motive into a melody of his own creation, Ives is not merely reflecting but refracting his understanding of Beethoven, hearing new possibilities in a familiar European musical gesture. Ives wrote: I remember feeling towards Beethoven [that he’s] a great man—but Oh for just one big strong chord not tied to any key … The more the ears have learned to hear, use and love sounds that Beethoven didn’t have, the more the lack of them is sensed naturally. 19

Throughout the Concord Sonata, the listener hears the Beethoven motive in numerous octave registers, dynamic ranges, rhythmic diminutions and augmentations, and harmonic contexts, including the kinds of dissonances “not tied to any key” that Ives imagined. Such troping on the Beethoven motive is already apparent on the first page of “Emerson”, as shown in Figure 2. In this way, Geoffrey Block suggests that in the Concord Sonata Ives was writing the music that, to his hears, “Beethoven would have composed had he been composing in 1915 rather than 1815.”20 With Emerson as his spiritual ancestor, Ives is dragging Beethoven to the New World and into the future. The larger point to be made here concerns Ives’s acute awareness of his place in the Western musical tradition, and in relation to a Eurocentric musical tradition in particular. Ives reveals himself as conscious of Beethoven’s iconic status in the history of Western music, but also as a believer in continued progress through time—and in himself as part of that progress beyond Beethoven. Ives was unique among American composers of his generation for eschewing the lure of Europe, remaining in America for his musical education. His teacher at Yale, Horatio Parker, had received his musical training in Germany and passed elements of that tradition down to his student. Burkholder traces the manifestation of traits inherited from the German Romantic tradition in Ives’s music. These include Ives’s use of European musical genres, such as symphony, sonata, and art song; his awareness of a musical canon that contains masterworks with which his own compositions must compete; his use of musical quotations from and allusions to other works; his interest in program music, and his use of literary, philosophical, and spiritual subjects in that music; the inclusion of apparently autobiographical instances in his music; the search for new means of expression while continuing to use traditional forms; and a spirit of nationalism. As radical as Ives’s music seems on the surface, Burkholder suggests, his “challenge is always from within the [European] tradition, not from outside it.”21 If Parker passed the German tradition down to his student, however, it must be understood as a German tradition passed through an American filter. Parker had also studied with the American composer George Chadwick, and encouraged Ives’s interest in Transcendentalism. As much as Ives worked within the European tradition, his highly idiosyncratic musical vocabulary must be understood as the product of an inter-cultural disjuncture between European aesthetic values and the various vernacular American musics with which Ives was also intimately familiar, and which made their way into the Concord Sonata. American patriotic songs, church music, ragtime music, and early jazz were part of Ives’s direct musical experience,22 resonating in his inner ear alongside—and mixed with—European art music. As a result, in the Concord Sonata, Ives creates a context, a musical environment, in which the Beethoven motive, pulled from its European roots, must be heard anew, transplanted to American soil, finally grown into his “human faith melody”. Ives’s sense of his musical environment, compared with that of Beethoven, is analogous to the difference between Emerson’s and Goethe’s understanding of nature. Beethoven’s music can be refracted into a wide range of meanings for a composer positioned in the musical wilderness of early-twentieth-century America, with its blurry intermingling of cultivated and vernacular,23 European and African influences. Like Emerson’s subjective view of history, his call for the reanimation of the past in the present, Ives’s juxtaposition of Beethoven against American vernacular music, his endless troping of the Beethoven motive in the Concord Sonata, gives rise to a musical environment in which the Beethoven motive is given the freedom to resound anew. In this way, Ives sought to create a world in which musical “history no longer shall be a dull book,” and new possibilities for interpreting the European tradition are given voice in America.

|

|||||||