| |

The Little Hoover Commission of California aims

at successfully integrating immigrants into the state, reducing

their exploitation and dependence, and harnessing their talents

for the state's benefit. In 2001 Assistant Professor of Public Policy

Studies at Duke University Noah M. Pickus testified before the commission

about the failure of California's integration policies in the early

20th century. According to Pickus, the failure partially stemmed

from the coercive policies of the teens and twenties. Forged in

a national context, Pickus' answer is apt.

However, as a method to teach immigrants their rights

and advocate for them, Americanization developed in California during

these years in a more complex manner than Pickus allows. In 1910

the U.S. census reported that over half of Californians or their

children were immigrants. The state responded to this fact and the

related need to make immigrants feel a part of the American fabric.

In California Americanization was many sided. It opposed disruptive

unionism, but was culturally liberal in many respects. If initially

skeptical about the prospects of incorporating Mexican and Asian

immigrants, it was more inclusive of Southeastern European immigrants

than the tenor of the time encouraged. It was strikingly anti-employer

when employers' actions threatened industrial peace, and unusually

careful in teaching immigrants their rights and duties as well as

teaching native-born Americans their obligations to potential citizens.1

While not synonymous with ours, the times likewise

undulated with prosperity and war with its attendant boom followed

by recession and depression. In general a number of external currents

influenced Americanization during the teens and twenties: the Progressive

movement with its faith in reshaping society through state intervention;

World War I and its call for patriotism, one hundred per cent Americanism,

and fear of all things foreign, particularly German; and the Red

Scare, which raised its head with the 1917 Bolshevik victory over

the Russian monarchy, intensifying the fear of foreign influences.

Each of these currents affected California in the realm of Americanization,

although not always in the way dictated in studies of the Progressive

movement or Americanization, which often focus on New York as the

trendsetter in immigrant policy of the time.

Progressive Influences

Among national debates that raged from the 19th into the 20th century

and were reignited in Congress after the assassination of President

McKinley by the son of Southeastern European immigrants was the

question of whether to exclude immigrants and if so, which ones,

based on the racial thinking of the era. A series of reforms enlarged

the categories of immigrants that were excludable. At the same time

other reformers emerged to champion what they called a domestic

immigration policy and what many reformers now refer to as immigrant

policy. This policy argued that the best way to deal with immigrant

unrest was to effectively integrate new comers into American life,

educate them about their rights, and eliminate un-American exploitation

that might lead such immigrants to rebel. This domestic immigration

policy movement was adopted between the teens and twenties in five

states, which contained over half of the country's population of

immigrants and their children. In these states - New York, Illinois,

Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, and California - reformers successfully

established agencies that worked to Americanize their residents,

both immigrant and native-born, and to eliminate the exploitation

beneath immigrant unrest. Trailing New York by a few years, California

was the second state to adopt an Americanization policy. Oriented

toward cultural pluralism, it was one of the most respectful of

immigrant differences for the time.

|

|

|

California received its Commission of Immigration

in Housing (CCIH) in 1913, as a result of the lobbying of a second-generation

immigrant, Simon J. Lubin, who emphasized the fact that California

was likely to receive an additional influx of Southeastern European

immigrants in 1914 when the Panama Canal opened. Four departments

- an Americanization department focusing on educating immigrants

in civics, a complaint department, a migrant labor camp department,

and a housing department worked together to facilitate immigrant

Americanization. Under Lubin and his fellow commissioners' auspices,

Americanization took on a unique form. Progressing from a harsher,

more racialist view under Amanda Matthews Chase, CCIH programs assumed

a softer tone under Lubin, Christina Krysto, and Ethel Richardson,

even as Americans faced increasing challenges from abroad.

As an organization CCIH perceived Americanization

not as a one way but a two way process in which both immigrants

and their native-born neighbors were expected to learn and act upon

the fundamental principals of citizenship. These principles involved

learning not only one's duties to the nation, but also one's rights;

and actively working to extend those rights to others in order to

reduce destabilizing and costly discontent. While the main beneficiaries

of this program were doubtless intended to be Southeastern Europeans,

and members of the commission left some very unpleasant remarks

about Asian and Mexican Americans on the historical register, both

visual and textual evidence contradicts commonly invoked assumptions

about the state's neglectful attitude towards the integration of

Asian and Mexican American minorities. California's Americanization

program involved all of the above groups and sought to enhance the

efficiency, productivity, and harmony of the state, as well as America's

image abroad. It did so through the influence of a small state bureaucracy

that engaged a broader civil society's voluntary organizations in

the service of encouraging Americans to live up to the principles

upon which the country was founded and teach all immigrants those

principles.

World War I

World War I intensified a fear that immigrants from the Axis powers,

Japan or Mexico might foment sabotage in the United States. California,

carved out of Mexico in 1848, shares a border with Mexico. This

together with concern that Germany would aid the Mexican government

retake its lost territories set Southwesterners on edge. In response

to this situation California's CCIH continued advocating a sympathetic

Americanization policy, but combined it with spying on the Industrial

Workers of the World (IWW), which led to a more repressive, yet

not employer-captive policy.

|

|

|

CCIH concern over IWW and a distrust of foreign

laborers, particularly Japanese and Mexicans, is reflected in its

1918 call for the establishment of permanent community labor camps.

CCIH community camp policy appeared only in 1918, a year after American

entry into the war and came under the direct influence of a number

of reports by its investigators. One such report by J.V. Thompson

aroused fear regarding the proposed German, Japanese, and Mexican

alliance. The report called for employer housing to eliminate the

congregation of certain races outside their employer's surveillance

and to limit the mobility of saboteurs. The proximity of Japanese

laborers to some of California's best beet and fruit ranches was

seen as an important threat to California's fruit industry. J.V.

Thompson noted that Japanese and Mexican laborers scattered around

various California counties "constitute[d] a menace...worthy of

observance;" and Mexican cowboys and laborers at the Miller and

Lux Company near Guadalupe, had "roundly cursed" President Woodrow

Wilson when they heard that the United States had recognized the

Carranza faction in Mexico.2

Thompson suggested eliminating IWW power in a multi-fold

way. He strove to get rid of the organization's headquarters, alleviate

labor camp conditions and prevent the mobility of laborers as well

as easy access to materials for sabotage. He urged employers "to

furnish transportation, and proper accommodations to their employees"

so that they might be kept under constant surveillance.3

Additional calls for internment fell on deaf ears. The federal government,

judging internment beyond existing legal avenues, favored a plan

that relied "entirely on legal actions...On September 5, 1917 Justice

Department agents and police officials invaded IWW homes and halls

across the nation and seized everything that they could find." Trials

were held in Fresno and Sacramento, California.4 The

raids did not stop IWW organizing in agriculture, copper mining,

lumber and other industries, and CCIH sent Thompson to investigate

the Redwood Empire's lumber industry in 1918.5

CCIH efforts against IWW might suggest that CCIH

was, in fact, captive to industry during the war. Tragically IWW

was one of the few unions that offered a voice for the unskilled

trades in which immigrants tended to congregate. However, it is

important to recognize that CCIH actions during the war were aimed

not against unionism, but violence. As William Preston, the author

of a history critical of the government's repression of IWW during

and immediately after WWI, points out, it is one thing to defend

civil liberties in free speech, another "to accept the continuous

violent action of the IWW's at the point of production."6

Like the Progressives, CCIH staff and commissioners distrusted the

organized economic power of corporations. Reflecting these two tendencies,

CCIH called both for the suppression of IWW and the vigilantism

practiced by corporations by placing repression in federal hands

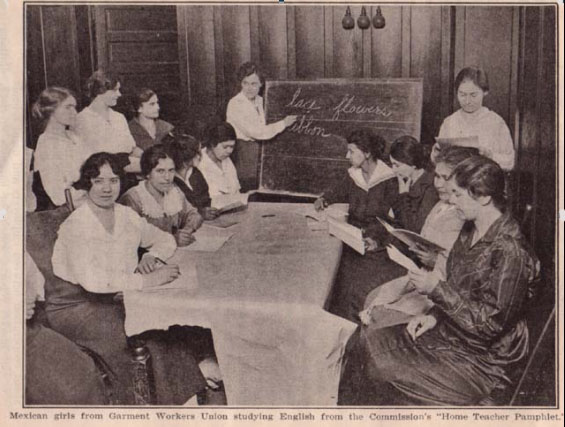

Beyond rhetoric, visual representations of CCIH

work suggest as much. Its labor camp department actively arrested

labor camp operators, especially as the war years waned and the

incentive for employers to follow CCIH proscriptions decreased.

Inspectors were sent into the field and a complaint department was

established that encouraged immigrant and migrant laborers to take

responsibility for their own living and working conditions ( Figure

1). The commission displayed an openness to sponsoring Americanization

classes under the auspices of any interested organization, including

the Garment Workers Union (Figure 2).

The Red Scare

While World War I raised the prospect of German, Japanese and Mexican

saboteurs, events in Russia during 1917 intensified Americans' sense

of vulnerability. That year, the Bolsheviks defeated the czars,

installing the world's first socialist government in one of the

least likely places. Insecure Americans began to see the threat

of Bolshevism in labor strikes and elsewhere. Unscrupulous opponents

of Progressive reform latched onto the general fear of the American

public as a way to attack social reforms, often successfully, parading

their destruction of Progressive policies as the triumph of Americanism.

Proponents of one type of Americanism (progressive, pluralistic)

battled it out with proponents of another (conservative, intensely

nationalistic, and committed to molding all into one culture). In

this combination of World War I and Red Scare-induced battles, CCIH,

like many other Progressive era agencies and reforms, was accused

of communist sympathies as illustrated in the election campaign

of California Governor Friend W. Richardson and the allegations

of the Better America Federation.

|

|

|

Tension over World War I renewed conservatism in

state and national affairs and in 1919 California passed a criminal

syndicalism law. Equally symptomatic of the backlash, but more induced

by the Red Scare, was the establishment of the Better America Federation

(BAF) in May 1920. As Edwin Layton shows, this reactionary organization

assaulted Progressive legislation - from higher taxes on banks and

utilities to the open shop to the eradication of all state regulatory

boards and commissions including CCIH. BAF accused its opponents

of treason and subversion, and specifically targeted Commissioner

and founder, Simon Lubin, and labor leader and Commissioner Paul

Scharrenberg. Meanwhile, the realignment of political parties in

California touted a business ideology that emphasized corporate

organization and efficiency as opposed to the social agencies' agendas.

This new administrative conservatism became institutionalized by

the 1923 election of Richardson as California's governor.7

BAF represents one of the earliest external challenges

to CCIH. As Edwin Layton notes, BAF campaigned to destroy many of

the Progressives' achievements using the same methods that Americanizers

employed during the war.8 Although CCIH ultimately discredited

BAF by exposing its private utility interest background, Lubin and

Scharrenberg were damaged by the assaults.9The militant

nationalism of World War I and the Red Scare encouraged BAF to use

Americanization rhetoric to discredit its opponents.10

For example, BAF accused Lubin and the commission of assisting the

IWW 11. It attacked Scharrenberg for drawing money from

CCIH while lobbying for anti-injunction bills that increased labor

unions' power in strikes.12 These attacks came at a vulnerable

moment in CCIH history.

Influenced by the Red Scare and the tarring of CCIH

with the taint of Communism, CCIH and the State Board of Education,

whose main Americanization program developer had been trained in

CCIH, took the offensive, promoting the need for Americanization

programs for immigrants and their extension to native-born Americans

throughout California. Indeed, in this volatile climate, CCIH actually

moved considerably to the left of Liberal Americanizers. Its proactive

approach to the challenges posed by the Red Scare was evident as

early as 1919. In 1919 and 1920, a series of articles entitled "The

Strength of the Nation" co-authored by commissioner Lubin and staff

member Christina Krysto appeared in The Survey.13 These

articles refuted the contemporary feeling that the melting pot was

not working, called for a federal department of nation building

with bureaus for the Americanization of both foreign-born and native-born

citizens, and reaffirmed CCIH belief that America's strength derived

from its power to take the talents of immigrants and "while preserving

their national core, to transmute them into a new thing that is

essentially American."14

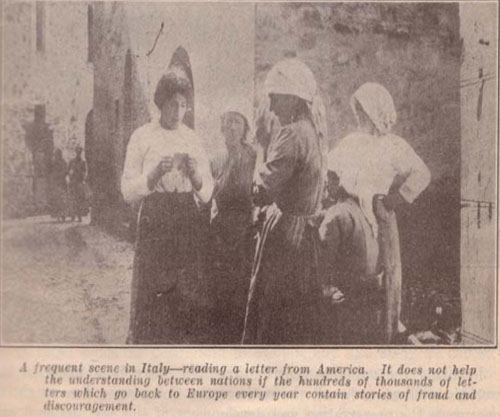

These articles placed novel emphasis on how the

treatment of immigrants influenced America's international image.

Americans were told that "when one section of the population is

a ready victim to exploitation, the moral tone of the whole land

is lowered."15 They were warned that the returned immigrant

became an example of American life to the homeland. "Returned emigrants

corrupted by the country they have visited, weakened by excessive

labor, impoverished by adverse industrial conditions, embittered

by a series of failures," would be "a burden to the home community

and a menace to the entire homeland"16, hardly likely

to project a good image of America (Figure 3).

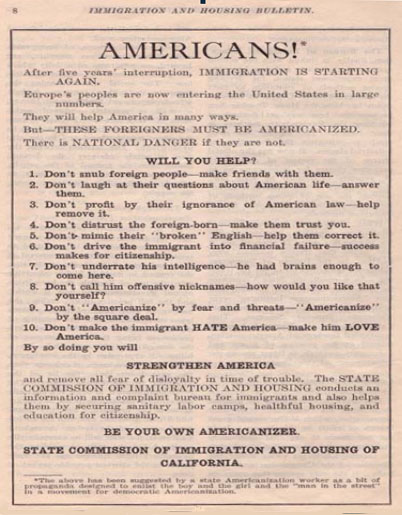

CCIH 1921 Annual Report argued "that Americanization

was not flag-raising and 'patriotic' howling; it was not suppression

of speech and honest opinion; it was more than teaching English

to foreigners" and involved the "Americanization" of Americans,

developing national ideals and standards in which "all residents,

foreign-born as well as native-born" would be schooled, especially

through community participation.17 CCIH launched a community

organization campaign in 1920 and 1921 insisting that Americans

should "be [their] own Americanizers"!18 Two posters

that appeared in its Bulletin clearly conveyed to social workers

and readers in general that instead of complaining about immigrants

as radical, unassimilated elements Americans ought to offer their

services to the state to solve the so-called problem (Figure 4).

Americanization was equated with raising all residents (whether

foreign or native-born) to a certain standard of living.

After World War I, CCIH continued to emphasize its

belief that immigrant cultures provided the best materials out of

which to build citizens. Moreover, while California's conservatives

won the immediate election, they lost the long-term battle. The

slashing of CCIH budgets by Governor Richardson was quickly reversed

when the governor became inundated by testimony about CCIH benefits

to the state from women's clubs, employers, and immigrant leaders.

Surely, in California during the teens and twenties,

Americanization was not about one hundred per cent Anglo-conformity

or teaching immigrants to accept a status quo that endangered the

industrial safety, health, and well-being of individuals and the

community at large. CCIH opposition to total Americanism influenced

the State Department of Education, which assumed responsibility

for immigrant education in 1920, along with its branch, the Bureau

of Immigrant Education (BIE) in California's Department of Adult

Education. The fact that Ethel Richardson, former Director of CCIH

Bureau of Immigrant Education served on all three of these bodies,

makes clear why this occurred.19 During the late 1920s,

BIE, which furnished the most material used in immigrant education

throughout the state, resisted demands for immigrant conformity.20

A 1925 BIE Community Exchange Bulletin proclaims that the "purpose

of the home teacher...is not to encourage the alien to forget his

native culture."21

|

|

|

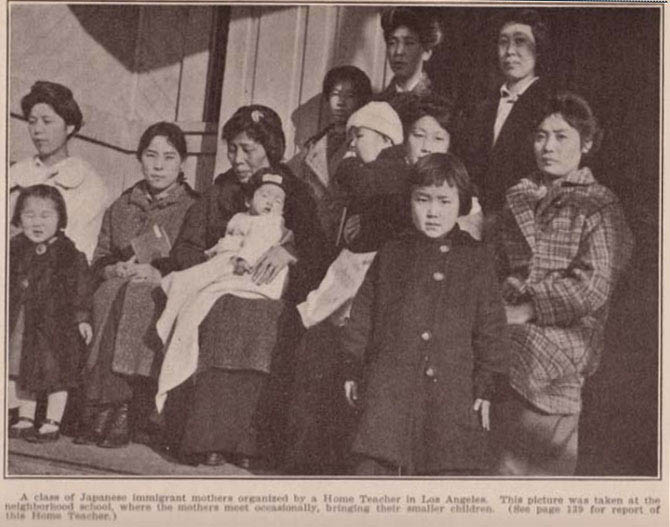

By the beginning of the Depression an uneven reversal

was underway. Those who experienced Americanization during that

era, particularly Mexican Americans, remember Americanization in

a harsher mode. Asian Americans, particularly Japanese Americans,

then subject to exclusion, found themselves subject to greater inclusion

at the same time.22 The decline in immigration and rise

in native-born children who were automatically American citizens

intensified the need to educate Asian immigrants, even though they

were denied the opportunity to naturalize. CCIH classes involving

Japanese Americans suggest this shift (Figure 5).

The advent of World War II and a bifurcated policy

that incarcerated Japanese Americans while embracing Chinese and

Filipino Americans starkly interrupted CCIH activity. Americanization

ultimately disappeared as a state policy in 1945, when CCIH immigrant

protective functions were abolished. Some fifty years later the

Little Hoover Commission reinvestigates this complex precedent as

one of a number of policies that might facilitate immigrant integration

in California for mutual benefit.

Notes>>

|

|