|

Americanizing Californians: Americanization in California from the Progressive Era through the Red Scare by Anne Woo-Sam |

|

|

The Little Hoover Commission of California aims at successfully integrating immigrants into the state, reducing their exploitation and dependence, and harnessing their talents for the state's benefit. In 2001 Assistant Professor of Public Policy Studies at Duke University Noah M. Pickus testified before the commission about the failure of California's integration policies in the early 20th century. According to Pickus, the failure partially stemmed from the coercive policies of the teens and twenties. Forged in a national context, Pickus' answer is apt.

However, as a method to teach immigrants their rights and advocate for them, Americanization developed in California during these years in a more complex manner than Pickus allows. In 1910 the U.S. census reported that over half of Californians or their children were immigrants. The state responded to this fact and the related need to make immigrants feel a part of the American fabric. In California Americanization was many sided. It opposed disruptive unionism, but was culturally liberal in many respects. If initially skeptical about the prospects of incorporating Mexican and Asian immigrants, it was more inclusive of Southeastern European immigrants than the tenor of the time encouraged. It was strikingly anti-employer when employers' actions threatened industrial peace, and unusually careful in teaching immigrants their rights and duties as well as teaching native-born Americans their obligations to potential citizens.1

While not synonymous with ours, the times likewise undulated with prosperity and war with its attendant boom followed by recession and depression. In general a number of external currents influenced Americanization during the teens and twenties: the Progressive movement with its faith in reshaping society through state intervention; World War I and its call for patriotism, one hundred per cent Americanism, and fear of all things foreign, particularly German; and the Red Scare, which raised its head with the 1917 Bolshevik victory over the Russian monarchy, intensifying the fear of foreign influences. Each of these currents affected California in the realm of Americanization, although not always in the way dictated in studies of the Progressive movement or Americanization, which often focus on New York as the trendsetter in immigrant policy of the time.

Progressive Influences

Among national debates that raged from the 19th into the 20th century

and were reignited in Congress after the assassination of President McKinley

by the son of Southeastern European immigrants was the question of whether

to exclude immigrants and if so, which ones, based on the racial thinking

of the era. A series of reforms enlarged the categories of immigrants

that were excludable. At the same time other reformers emerged to champion

what they called a domestic immigration policy and what many reformers

now refer to as immigrant policy. This policy argued that the best way

to deal with immigrant unrest was to effectively integrate new comers

into American life, educate them about their rights, and eliminate un-American

exploitation that might lead such immigrants to rebel. This domestic immigration

policy movement was adopted between the teens and twenties in five states,

which contained over half of the country's population of immigrants and

their children. In these states - New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts,

and California - reformers successfully established agencies that worked

to Americanize their residents, both immigrant and native-born, and to

eliminate the exploitation beneath immigrant unrest. Trailing New York

by a few years, California was the second state to adopt an Americanization

policy. Oriented toward cultural pluralism, it was one of the most respectful

of immigrant differences for the time.

|

California received its Commission of Immigration in Housing (CCIH) in 1913, as a result of the lobbying of a second-generation immigrant, Simon J. Lubin, who emphasized the fact that California was likely to receive an additional influx of Southeastern European immigrants in 1914 when the Panama Canal opened. Four departments - an Americanization department focusing on educating immigrants in civics, a complaint department, a migrant labor camp department, and a housing department worked together to facilitate immigrant Americanization. Under Lubin and his fellow commissioners' auspices, Americanization took on a unique form. Progressing from a harsher, more racialist view under Amanda Matthews Chase, CCIH programs assumed a softer tone under Lubin, Christina Krysto, and Ethel Richardson, even as Americans faced increasing challenges from abroad.

As an organization CCIH perceived Americanization not as a one way but a two way process in which both immigrants and their native-born neighbors were expected to learn and act upon the fundamental principals of citizenship. These principles involved learning not only one's duties to the nation, but also one's rights; and actively working to extend those rights to others in order to reduce destabilizing and costly discontent. While the main beneficiaries of this program were doubtless intended to be Southeastern Europeans, and members of the commission left some very unpleasant remarks about Asian and Mexican Americans on the historical register, both visual and textual evidence contradicts commonly invoked assumptions about the state's neglectful attitude towards the integration of Asian and Mexican American minorities. California's Americanization program involved all of the above groups and sought to enhance the efficiency, productivity, and harmony of the state, as well as America's image abroad. It did so through the influence of a small state bureaucracy that engaged a broader civil society's voluntary organizations in the service of encouraging Americans to live up to the principles upon which the country was founded and teach all immigrants those principles.

World War I

World War I intensified a fear that immigrants from the Axis powers, Japan

or Mexico might foment sabotage in the United States. California, carved

out of Mexico in 1848, shares a border with Mexico. This together with

concern that Germany would aid the Mexican government retake its lost

territories set Southwesterners on edge. In response to this situation

California's CCIH continued advocating a sympathetic Americanization policy,

but combined it with spying on the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW),

which led to a more repressive, yet not employer-captive policy.

|

CCIH concern over IWW and a distrust of foreign laborers, particularly Japanese and Mexicans, is reflected in its 1918 call for the establishment of permanent community labor camps. CCIH community camp policy appeared only in 1918, a year after American entry into the war and came under the direct influence of a number of reports by its investigators. One such report by J.V. Thompson aroused fear regarding the proposed German, Japanese, and Mexican alliance. The report called for employer housing to eliminate the congregation of certain races outside their employer's surveillance and to limit the mobility of saboteurs. The proximity of Japanese laborers to some of California's best beet and fruit ranches was seen as an important threat to California's fruit industry. J.V. Thompson noted that Japanese and Mexican laborers scattered around various California counties "constitute[d] a menace...worthy of observance;" and Mexican cowboys and laborers at the Miller and Lux Company near Guadalupe, had "roundly cursed" President Woodrow Wilson when they heard that the United States had recognized the Carranza faction in Mexico.2

Thompson suggested eliminating IWW power in a multi-fold way. He strove to get rid of the organization's headquarters, alleviate labor camp conditions and prevent the mobility of laborers as well as easy access to materials for sabotage. He urged employers "to furnish transportation, and proper accommodations to their employees" so that they might be kept under constant surveillance.3 Additional calls for internment fell on deaf ears. The federal government, judging internment beyond existing legal avenues, favored a plan that relied "entirely on legal actions...On September 5, 1917 Justice Department agents and police officials invaded IWW homes and halls across the nation and seized everything that they could find." Trials were held in Fresno and Sacramento, California.4 The raids did not stop IWW organizing in agriculture, copper mining, lumber and other industries, and CCIH sent Thompson to investigate the Redwood Empire's lumber industry in 1918.5

CCIH efforts against IWW might suggest that CCIH was, in fact, captive to industry during the war. Tragically IWW was one of the few unions that offered a voice for the unskilled trades in which immigrants tended to congregate. However, it is important to recognize that CCIH actions during the war were aimed not against unionism, but violence. As William Preston, the author of a history critical of the government's repression of IWW during and immediately after WWI, points out, it is one thing to defend civil liberties in free speech, another "to accept the continuous violent action of the IWW's at the point of production."6 Like the Progressives, CCIH staff and commissioners distrusted the organized economic power of corporations. Reflecting these two tendencies, CCIH called both for the suppression of IWW and the vigilantism practiced by corporations by placing repression in federal hands

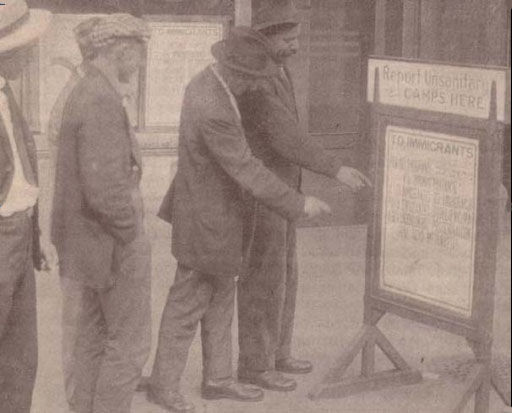

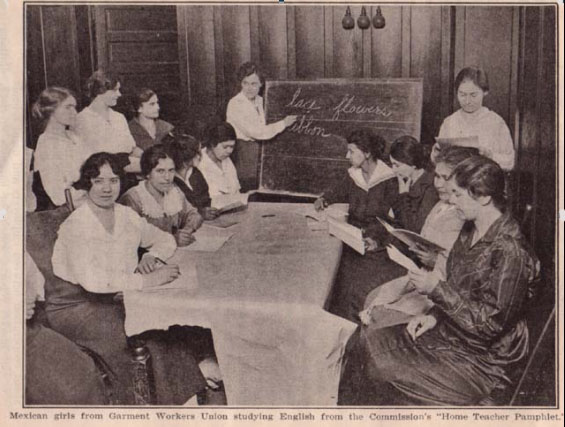

Beyond rhetoric, visual representations of CCIH work suggest as much. Its labor camp department actively arrested labor camp operators, especially as the war years waned and the incentive for employers to follow CCIH proscriptions decreased. Inspectors were sent into the field and a complaint department was established that encouraged immigrant and migrant laborers to take responsibility for their own living and working conditions ( Figure 1). The commission displayed an openness to sponsoring Americanization classes under the auspices of any interested organization, including the Garment Workers Union (Figure 2).

The Red Scare

While World War I raised the prospect of German, Japanese and Mexican

saboteurs, events in Russia during 1917 intensified Americans' sense of

vulnerability. That year, the Bolsheviks defeated the czars, installing

the world's first socialist government in one of the least likely places.

Insecure Americans began to see the threat of Bolshevism in labor strikes

and elsewhere. Unscrupulous opponents of Progressive reform latched onto

the general fear of the American public as a way to attack social reforms,

often successfully, parading their destruction of Progressive policies

as the triumph of Americanism. Proponents of one type of Americanism (progressive,

pluralistic) battled it out with proponents of another (conservative,

intensely nationalistic, and committed to molding all into one culture).

In this combination of World War I and Red Scare-induced battles, CCIH,

like many other Progressive era agencies and reforms, was accused of communist

sympathies as illustrated in the election campaign of California Governor

Friend W. Richardson and the allegations of the Better America Federation.

|

Tension over World War I renewed conservatism in state and national affairs and in 1919 California passed a criminal syndicalism law. Equally symptomatic of the backlash, but more induced by the Red Scare, was the establishment of the Better America Federation (BAF) in May 1920. As Edwin Layton shows, this reactionary organization assaulted Progressive legislation - from higher taxes on banks and utilities to the open shop to the eradication of all state regulatory boards and commissions including CCIH. BAF accused its opponents of treason and subversion, and specifically targeted Commissioner and founder, Simon Lubin, and labor leader and Commissioner Paul Scharrenberg. Meanwhile, the realignment of political parties in California touted a business ideology that emphasized corporate organization and efficiency as opposed to the social agencies' agendas. This new administrative conservatism became institutionalized by the 1923 election of Richardson as California's governor.7

BAF represents one of the earliest external challenges to CCIH. As Edwin Layton notes, BAF campaigned to destroy many of the Progressives' achievements using the same methods that Americanizers employed during the war.8 Although CCIH ultimately discredited BAF by exposing its private utility interest background, Lubin and Scharrenberg were damaged by the assaults.9The militant nationalism of World War I and the Red Scare encouraged BAF to use Americanization rhetoric to discredit its opponents.10 For example, BAF accused Lubin and the commission of assisting the IWW 11. It attacked Scharrenberg for drawing money from CCIH while lobbying for anti-injunction bills that increased labor unions' power in strikes.12 These attacks came at a vulnerable moment in CCIH history.

Influenced by the Red Scare and the tarring of CCIH with the taint of Communism, CCIH and the State Board of Education, whose main Americanization program developer had been trained in CCIH, took the offensive, promoting the need for Americanization programs for immigrants and their extension to native-born Americans throughout California. Indeed, in this volatile climate, CCIH actually moved considerably to the left of Liberal Americanizers. Its proactive approach to the challenges posed by the Red Scare was evident as early as 1919. In 1919 and 1920, a series of articles entitled "The Strength of the Nation" co-authored by commissioner Lubin and staff member Christina Krysto appeared in The Survey.13 These articles refuted the contemporary feeling that the melting pot was not working, called for a federal department of nation building with bureaus for the Americanization of both foreign-born and native-born citizens, and reaffirmed CCIH belief that America's strength derived from its power to take the talents of immigrants and "while preserving their national core, to transmute them into a new thing that is essentially American."14

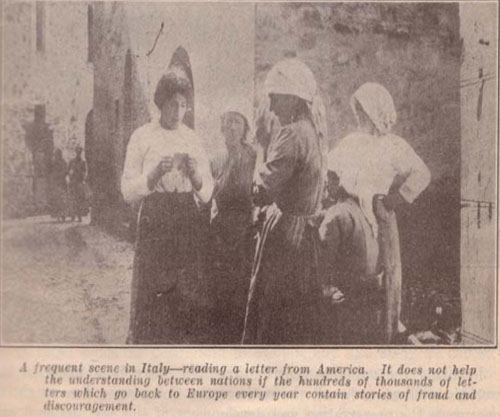

These articles placed novel emphasis on how the treatment of immigrants influenced America's international image. Americans were told that "when one section of the population is a ready victim to exploitation, the moral tone of the whole land is lowered."15 They were warned that the returned immigrant became an example of American life to the homeland. "Returned emigrants corrupted by the country they have visited, weakened by excessive labor, impoverished by adverse industrial conditions, embittered by a series of failures," would be "a burden to the home community and a menace to the entire homeland"16, hardly likely to project a good image of America (Figure 3).

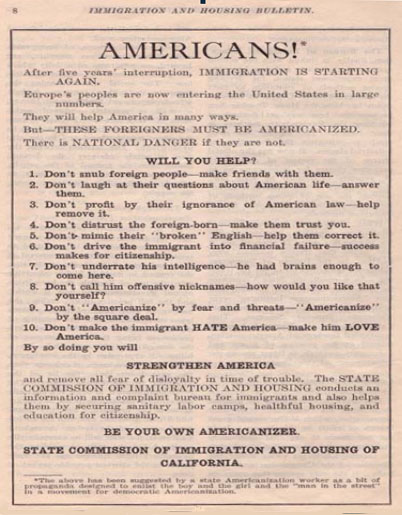

CCIH 1921 Annual Report argued "that Americanization was not flag-raising and 'patriotic' howling; it was not suppression of speech and honest opinion; it was more than teaching English to foreigners" and involved the "Americanization" of Americans, developing national ideals and standards in which "all residents, foreign-born as well as native-born" would be schooled, especially through community participation.17 CCIH launched a community organization campaign in 1920 and 1921 insisting that Americans should "be [their] own Americanizers"!18 Two posters that appeared in its Bulletin clearly conveyed to social workers and readers in general that instead of complaining about immigrants as radical, unassimilated elements Americans ought to offer their services to the state to solve the so-called problem (Figure 4). Americanization was equated with raising all residents (whether foreign or native-born) to a certain standard of living.

After World War I, CCIH continued to emphasize its belief that immigrant cultures provided the best materials out of which to build citizens. Moreover, while California's conservatives won the immediate election, they lost the long-term battle. The slashing of CCIH budgets by Governor Richardson was quickly reversed when the governor became inundated by testimony about CCIH benefits to the state from women's clubs, employers, and immigrant leaders.

Surely, in California during the teens and twenties, Americanization

was not about one hundred per cent Anglo-conformity or teaching immigrants

to accept a status quo that endangered the industrial safety, health,

and well-being of individuals and the community at large. CCIH opposition

to total Americanism influenced the State Department of Education, which

assumed responsibility for immigrant education in 1920, along with its

branch, the Bureau of Immigrant Education (BIE) in California's Department

of Adult Education. The fact that Ethel Richardson, former Director of

CCIH Bureau of Immigrant Education served on all three of these bodies,

makes clear why this occurred.19 During the late 1920s, BIE,

which furnished the most material used in immigrant education throughout

the state, resisted demands for immigrant conformity.20 A 1925

BIE Community Exchange Bulletin proclaims that the "purpose of the home

teacher...is not to encourage the alien to forget his native culture."21

|

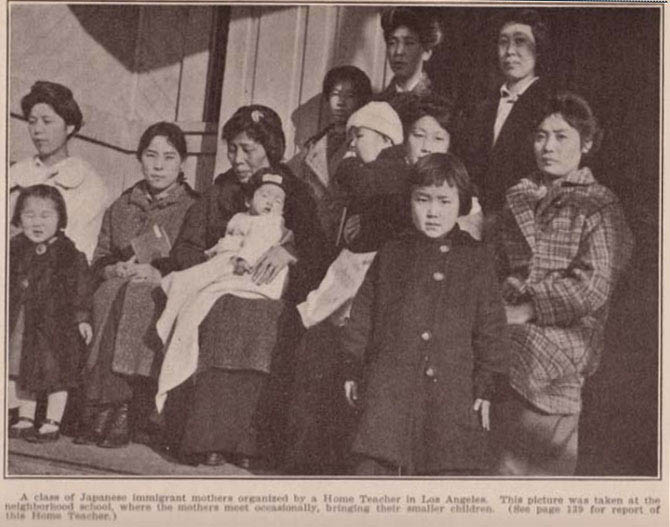

By the beginning of the Depression an uneven reversal was underway. Those who experienced Americanization during that era, particularly Mexican Americans, remember Americanization in a harsher mode. Asian Americans, particularly Japanese Americans, then subject to exclusion, found themselves subject to greater inclusion at the same time.22 The decline in immigration and rise in native-born children who were automatically American citizens intensified the need to educate Asian immigrants, even though they were denied the opportunity to naturalize. CCIH classes involving Japanese Americans suggest this shift (Figure 5).

The advent of World War II and a bifurcated policy that incarcerated Japanese Americans while embracing Chinese and Filipino Americans starkly interrupted CCIH activity. Americanization ultimately disappeared as a state policy in 1945, when CCIH immigrant protective functions were abolished. Some fifty years later the Little Hoover Commission reinvestigates this complex precedent as one of a number of policies that might facilitate immigrant integration in California for mutual benefit.