|

Jean Xceron: Neglected Master and Revisionist Politics by Thalia Vrachopoulos |

"Most artists are with you and that is the greatest level of appreciation."-David Smith to Jean Xceron 1

|

Jean Xceron (1890-1967) was an American modernist pioneer who in his lifetime enjoyed renown and was regarded as a forerunner to American abstraction but who, for numerous reasons, has fallen into obscurity. Whereas he had gained a measure of success in his lifetime, since his death his importance has faded while his impact on other American artists has been trivialized. The resulting lacuna of data combined with some fragmentary misinformation has also served to suppress his significance. Xceron's role as a vital link between what is commonly termed as the first-generation (the Stieglitz group, the Synchromists, etc.) and second-generation (the American Abstract Artists, the Transcendental Painting Group, George L.K. Morris, Ibram Lassaw, etc.) of abstract artists in America2 and between the Parisian Cercle et Carré, Abstraction Création and the American Abstract Artists groups in the thirties, should be recognized. The division between first and second generation American abstraction is a false one, resulting in the ironic belief that there was a break in American abstraction between the World Wars. As evinced by the existence and work of masters such as Xceron,3 Arshile Gorky, Raymond Jonson, John Graham and many others, American abstraction never actually died out but became less popular between the World Wars. Furthermore, because Xceron's early works are unknown, he has been characterized by his best known, more familiar post-1940s style, which has been described as rectilinear, grid-like or Mondrianesque, another irony.4 Consequently, Xceron has been placed within the category of second-generation American abstraction and his earlier accomplishments have been rendered obscure. However, a re-examination of the early sources and the recent discovery of Xceron works from the early 1930s reveals he was continuously creating abstract works from 1916 to 1932. After this period, Xceron's style became purely abstract and remained so for the rest of his life. In reviewing these thorny issues for the purpose of rectifying some commonly held misconceptions, the author hopes to clarify Xceron's meritorious role and its context in American art, and to bring about a better understanding of his painting.

Xceron's given name was Yiannis Xirocostas. He was born in 1890 in Isary, Greece, and came to the United States in 1904 at the age of fourteen. He lived with various relatives across the country until 1911-1912, when he began studying at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C. His surname was eventually changed to Xceron. He was called John (the English equivalent of Yannis) in America and Jeanduring the years he spent in France. In 1913, Xceron and his classmates Abraham Rattner, Leo Logasa and George Lohr, were deeply affected by the innovative style of the modern works in the Armory Show. In the Armory Show's aftermath and after several traveling venues some works from this show went to Alfred Stieglitz, whose gallery at that time was one of the few to champion modernism. Xceron and his colleagues borrowed some of the Armory Show works from Stieglitz to mount their own version of the show in Washington, D.C.5 Consequently, Xceron and his cadre earned reputations as revolutionaries for attempting Cézannesque interpretations of their subjects rather than following prescribed academic methods.

After graduating from the Corcoran, Xceron went to New York to study independently, and by 1920 was exhibiting with the Society of Independent Artists and associating with its member artists Joseph Stella, Max Weber, and Abraham Walkowitz. A representative work of that period is Landscape #36, 1923, a gouache on board, which is a study after Cezanne that demonstrates Xceron's expertise with transparent space that would be recognized as a key characteristic of his mature style. A cottage in the woods is depicted in passages of brown, green, and neutral shades and exhibits various figure-ground ambiguities as a result of the interchangeability of the rectangular strokes. The tree trunks on the right of the composition are clearly read as foreground whereas the tree shapes on the left appear to be in the middle ground and to pull towards the back. The flatness of the cottage and the adjoining trees seemingly growing from its gabled roof render an ambiguous reading. The overall effect is one of veils of transparent color as if the forest has been draped with delicate chiffon material.

Xceron should have been recognized in the scholarly literature as part of this early American avant-garde, but because his documents, records and early works had been lost or became otherwise unavailable, he has remained relatively unknown. More recent scholarship and uncovered sources of personal archives show that Xceron was familiar with the international artistic milieu as well. One of these artists was the Uraguyan Joachin Torres-Garcia, with whom he corresponded after Torres-Garcia went to Paris in the early twenties. In 1930, when Xceron went to Paris, Torres-Garcia invited him to join his newly formed group the Cercle et Carré. Kimon Nikolaides, Xceron's Corcoran colleague who became a well-known Art Students League teacher, invited Xceron to deliver a lecture on abstraction at the League.7 Xceron's link to this school is important because several of its members would have a future impact on the Abstract Expressionists. And, directly (through the Garland Gallery Exhibition and through his images in Cahiers d'Art) and indirectly (through his connections to the teachers of the League) so would Xceron. But whereas the latter has never been studied for his influential role, Graham recently has been found to be of seminal importance to Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning.

Another important event in Xceron's life in New York during the twenties was meeting the Greek Dada poet Theodoros Dorros, who inspired him to break further with his academic past. Dorros, a mysterious character in the true sense of the Duchampian Dada spirit, was a Socialist who wrote Dada poetry, which he published himself so that he could maintain an independent voice. He was known to present gift copies of his poetry books to libraries as he did to the New York Public Library in order to promote his beliefs.8 He is recognized in Greece as a Dada forerunner but there is still very little information available on this Greek poet.9 Concentrated research has revealed that while supporting himself as a tailor in the family's fashion business in New York and its subsidiary in Paris, he wrote both Dada poetry and socialist literature. Because the Dorros family owned a fashion concern and had roots in Paris, he was able to help Xceron when the artist arrived in that city, and introduced him to his sister Mary, whom Xceron married in 1935.

Perceived as too pragmatic, materialistic and commercial by many artists, the atmosphere of New York in the twenties became constricting to these modernists -- some of who sought alternatives in Paris. Xceron and Torres-Garcia were two such artists seeking a more amenable working climate; less invested in materialism and more agreeable to artistic concerns. In 1927, with many letters of introduction including one from Abraham Rattner who knew the editor of the Herald Tribune, and the help of the Dorros family, Xceron went to Paris to further his career. Initially he wrote art reviews as a syndicated art columnist for the European editions of the Chicago Herald Tribune, BostonEvening Transcriptand New YorkHerald Tribune, newspapers which were widely read by Americans abroad as well as at home. Therefore, Xceron's role as disseminator and link between the Parisian and American avant-gardes actually began as an art critic. He not only reported on but became acquainted with Julio Gonzalez, Jean Arp, Sophie Teuber Arp, Robert and Sonia Delaunay, Natalie Goncharova, Piet Mondrian, El Lissitzky, Theo Van Doesburg, Michel Larionov, and Vasily Kandinsky. He also announced such events as exhibitions, performances, recitals, and concerts.10

Through the Greek Diaspora in Paris Xceron came in contact with the Christian Zervos coterie and was introduced to Juan Gris and Efstratios Tèriade. Tèriade wrote about his work and gave him entrée to many other prestigious circles.11 By 1928, Xceron exhibited several abstracted nude studies at the Galerie Dalmau in Barcelona with friends from Paris including Jean Hélion and Torres-Garcia. Xceron's 1931 one-man show at the Galerie de France was so well attended and successful in its critical reception that it signaled the inception of Xceron's artistic renown. It was also at this juncture that Xceron's name and works began appearing regularly in the French press, especially in L'Intransigeant and Zervos's Cahiers d'Art. Tèriade, Zervos, André Salmon and Maurice Raynal, four of the most important art critics in Paris in the early thirties, wrote reviews of Xceron's biomorphic works made at this time. Two particular works, both entitled Peinture, and done in oil on canvas in 1932-1934, were reproduced in Cahiers d'Art12 Xceron's biomorphic abstractions and collages were informed not only by natural processes (as were Jean Arp's concretions) but also contained the elements of chance and automatist gesture found in Dada. It should be pointed out here that the earlier experience with the Dada poet Dorros was seminal in this regard. But, Jean Arp's work also inspired him and he had reviewed Arp's show in the July 20th, 1929 issue of the Chicago Tribune. The importance of Xceron's biomorphic pieces increases exponentially when considered as typical examples of his early thirties style, which is Dadaist. It also serves as proof that Xceron's biomorphic works inspired American artists such as Arshile Gorky, David Smith, and William Baziotes, who were known to read the Cahiers d'Art in which Xceron's work was often reproduced.One seminal figure that brought these publications back to the United States for other American artists to read was John Graham, with whom many of the Art Students League circle were acquainted. In fact, Graham traveled to Paris very often and used Xceron's address to receive his mail. The proximity of these two artists resulted in a medley of erroneous conclusions mistaking one John for the other and causing some misattributions. To complicate things further, Hilla Rebay, then the director of the Museum of Non-Objective Painting (now known as the Solomon R.Guggenheim Museum of Art), employed both John (in French Jean) Xceron and John Graham. Consequently, American critics often confused the two painters and attributed credit to John Graham for David Smith's biomorphic or Surrealist influences while a closer inspection of the documents and a re-examination of dates and facts renders proof that it was Xceron whom Smith was thanking in his letters for Xceron's influence and advice.13.

An event of special significance to American artists in 1935 was Xceron's Garland Gallery exhibition, but the reasons for this success are not immediately evident until the art and political contexts of New York in 1935 are scrutinized.14 Then it is discovered that exhibitions containing abstract art, such as Xceron's, were rare events and that American artists were eager to see the latest styles from Paris. The Depression had taken its toll and the prevalent artistic styles were figurative, while abstraction was still considered experimental and unsuitable for expressing political polemic. The brothers Max and Joseph Felshin, early advocates of abstraction, owned the Garland Gallery on 57th Street. But since the gallery's closing in the early forties, the Felshins have fallen into obscurity, leaving us with very little documentation on the history of this space. In fact, only a careful reconstruction of the events from various archives rendered proof of which Xceron works were shown at the Garland, what was their style, and what were some of the names of those who attended the events. In discovering the Felshin paintings Composition 120, 1934 (Fig. 1) and La Musique, 1933, it is evidenced that Xceron was working in abstract biomorphism foreshadowing many Americans, such as Gorky, and that stylistically and chronologically these paintings are consistent with those of the same period in the Zervos Collection. However, Xceron's impact on American artists can be found not only in the numerous interviews and writings by Ilya Bolotowsky, David Smith, and Borgoyne Diller, but also in comparisons between their works and his.15 As an avant-garde exhibition of the latest styles from Paris, the 1935 Xceron show at the Garland garnered profuse press reviews. Some of these were very positive and most demonstrated the contextual proclivity for figurative models of art which, rather than hindering the reception of Xceron's work, made it all the more appealing to abstract artists in America. That Xceron also enjoyed some commercial success at this time is seen by the addition of his works to Eugene Gallatin's Museum of Living Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Phillips Memorial Collection. In addition, the artist also held the distinction of being one of the earliest abstractionists to be offered a position with the WPA/FAP at its inauguration in 1935, in Washington, D.C.; but rather than accept it, he returned to Paris for another two years.16

|

|

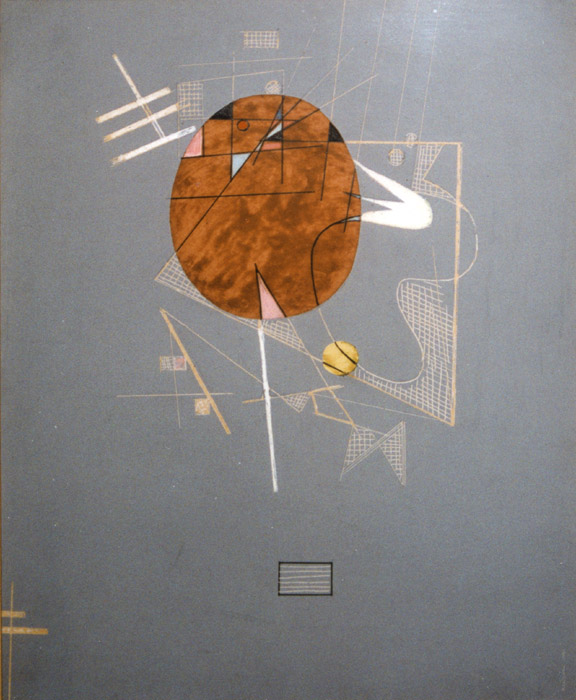

Fig 2:

Collage. 1932

|

Remaining in Paris until 1937, when the increasingly fascist political climate became intolerable for artists, Xceron returned home to America permanently. However, during these two years abroad, Xceron continued his activities with the Parisian avant-garde and the group Abstraction Création, while exhibiting with the Surindependents, Realités Nouvellesand Cahiers d'Art. Xceron's early Greek rearing among the classical antiquities in his native town and an education in classical philosophy, instilled in him the need for synthesis equated with the ideal; and by 1935 he combined the biomorphic with increasingly strong compositional order as seen in his Collageof 1932. (Fig. 2) This mixed-media work evinces the increasing focus on space resulting in linear shapes combined with the previous biomorphic tendency. The collage medium learned from his study of both Picasso's and Arp's compositions is adeptly handled and laid upon a simple gray ground. The oval rust form slightly off left center seemingly floats and is composed of delicate shades of rust with gridded designs within its top portion. Surrounding this motif are off-white elements in biomorphic and linear shapes that have been expertly scratched onto the surface. This sgraffito was commonly used in Archaic vase painting but was also a favored method with Picasso who studied Greek vases at length. Xceron admired Picasso and Julio Gonzalez and it would be futile to deny his debt to these masters. It is commonly known that Gonzalez showed Picasso his working methods in welding metal, and that Picasso created his line works based upon this technology. Picasso's use of line as seen in his 1928 work Study for Sculpture (Zervos VII, 206) can be compared to Xceron's Study #73, 1932, which was done in ink and pencil on paper. Both works exhibit the use of line in alluding to the figure, but whereas Picasso's is rectilinear, Xceron's line is softer and flowing. In fact, Xceron had much in common with Picasso, a known Philhellene whose work also appeared in Zervos' Cahiers d'Artand about whose works Tèriade wrote for L'Intransigeant.

When Xceron returned to the United States, his style was totally abstract, and is exemplified by Composition, 1937, an oil on canvas which exhibits resolution and synthesis in his use of form and space. Space is implied by soft shades of browns, turquoises and pinks that imply transparency, while the composition as a whole contains both rectilinear and curvilinear elements. From here forward, Xceron worked with the elements of his own personally developed abstract language to create compositions with content and meaning but that appear abstract or non-referential.

|

|

Fig 3:

Composition No. 242, 1937

|

The year 1937 signified a period of great success for Xceron as numerous American artists sought his advice. Triumph after triumph followed as Xceron was patronized by such influential figures as Alfred Barr Jr., who collected his work for the Museum of Modern Art, Russel C. Parr and Holger Cahill, whose recommendations to the FAP/PWA resulted in the Riker's Island mural commission, and Rebay, who as director of the Museum of Non-Objective Art, employed him to work for the museum as custodian (the equivalent of a registrar today) of paintings. Rebay had supported Xceron's studies abroad since 1930, and had bought several works from his 1937 Nierendorf Gallery show that further promoted his fame among modern American art audiences. Composition No. 242, 1937 (Fig. 3) was one of the works she purchased from the Nierendorf exhibition for Solomon R. Guggenheim.

Xceron

had always been ambivalent about joining any group and usually remained

at its periphery, but due to his affiliation with Rebay, he was even

more divided about becoming a member of the American Abstract Artists.

Nevertheless, he joined them in 1938 but did not show with them with

any regularity. Rebay had supported him financially, employed

him, promoted his career and deserved his loyalty, but was at ideological

odds with this group. A public debate ensued as the American Abstract

Artists collectively objected to Rebay's "ivory tower" aesthetics stating

that abstract art is part of life: "having basis in living actuality."

19 The political climate of the United States in the late

thirties and early forties was not sympathetic to abstraction, and pandered

to public opinion informed by the need to express clarity and national

values. Consequently, American abstract artists felt unsupported

by the Museum of Non-Objective Art, whose collection contained works

idiosyncratically defined by Rebay as "non-objective" art, and the Museum

of Modern Art, which owned mostly European works. They also felt

betrayed by the public who preferred figuration. Abstractionists

were criticized for being apolitical or unpatriotic because their styles

were perceived as incapable of expressing political ideology.

Abstract artists objected to Rebay's idiosyncratic use of the term "non-objective"

to define abstract art. 18 An example of the negative

press Rebay received was written by Charles Robbins, who claimed to

represent public sentiment: "As a glance at the examples on this page

will show, non-objective painting to the uninitiated, looks like a cross

between a doodle and a blueprint drawn by a cockeyed draughtsman on

a spree." 19 Difficult as that period was for Xceron

and American abstract artists, and despite his problematic and precarious

political situation, he was an important link between American and European

art when many European artists (such as Leger, Mondrian, and Hélion)

immigrated to America as Fascism rose in Europe. Many of them

joined the American Abstract Artists. This group was known for

its proclivity towards a rectilinear style inspired by Mondrian who

immigrated to the United States in 1941 and who joined this group.

In the forties, Xceron was also working in a linear style, but not with

pure colors as Mondrian and not in strict geometry. Nevertheless,

American audiences are most familiar with this period of his work, ergo

the assumption that he was a follower of Mondrian. It was to Xceron

that Mondrian first wrote for help when fascist Europe became too dangerous

for artists to stay. In the end, Xceron could not invite Mondrian,

who was aided by Harry Holtzman instead, but they remained friends from

their Paris days in 1928 until the older master's death in 1944.

A typical Xceron composition is an oil on canvas such as Painting

#294of 1946 (Fig. 4), in which the artist's rectilinear preferences

of that era are seen in the grid-like elements both at the top and bottom

left sectors. However, unlike the flat, opaque, coloristic tendencies

in Bolotowsky's or Diller's paintings, Xceron's modulated shades of

plum and lilac fade into the distance to imply transparent space.

|

|

Fig 4:

Painting #294, 1946

|

In the forties and fifties, Xceron was the custodian of paintings for the Guggenheim Museum, whose collection was housed at a Manhattan warehouse. He was allowed to paint there in his spare time while also receiving many visitors. Mark Rothko, David Smith, Ibram Lassaw, Ilya Bolotowsky, Will Barnet, William Baziotes, and Nassos Daphnis are some of the many artists to whom Xceron showed his and the Guggenheim's paintings. Most were familiar with Xceron's work through their reproduction in Cahiers d'Artand the 1935 Garland Gallery show. Xceron enjoyed many solo exhibitions and was included in most of the Guggenheim non-objective painting group exhibitions throughout his life. The artist also showed with such venues as the American Abstract Artists, American Federation of Artists, Carnegie Institute, Federation of Modern Painters and Sculptors, International Council of the Museum of Modern Art, Salon de Realités Nouvelles, Salon des Surindependants, Society of Independent Artists, Toledo Museum of Art, University of Illinois, and the Whitney Museum of American Art. By 1946, Xceron had achieved further prominence and was commissioned by the University of Georgia to do a painting that he entitled Radar(Fig. 5), which reflects the contemporary interest in the marriage of art and science. 20 This oil on canvas encapsulates Xceron's oeuvre up to that time due to its softly modulated floating spatial organization, which contains positive and negative circular geometric and gestural forms radiating out that are echoed throughout its surface. This important work was widely publicized and marks Xceron's active engagement with the style that would later become known as Abstract Expressionism.

|

|

Fig 5:

Radar, 1946

|

Finally, through contextualization and examination of newly found key works, the author hopes that Xceron's contributions to American art between the World Wars has been clarified, bridging the falsely created gap in American abstraction between the assumed division of first and second generations. The detection of the Zervos Dada automatist works in addition to the Felshin surrealist pieces, along with the recently found documents, have supported Xceron's position in early American abstraction, and have proved that American abstraction certainly never died but rather that its popularity sometimes waned. Xceron created art in an abstracted style starting in 1916 while at the Corcoran, and by 1927 he had engaged in automatist drawings and collages, resulting in total abstraction by 1933-34 in the Zervos and Felshin works. As such, he is one of the enduring masters of American modern art who persevered in his engagement with abstraction up to his death in 1967.