| PART | | Journal of the CUNY PhD Program in Art History |

|

|||||||||||||||||

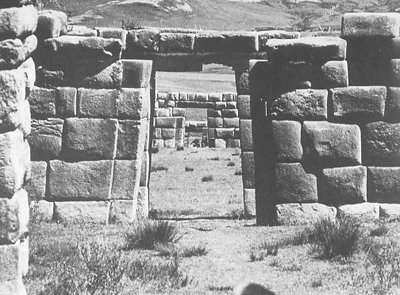

| The following is a revised version of the essay that originally appeared here. The revised version was uploaded June 15, 2007. Inka designers often placed frames or bordering devices around seemingly natural boulders, structures and even the common pathways of elite individuals. The low-lying stone wall surrounding the “Seated Puma Stone” at Qenko, Peru (Figure 1) is one example as is the series of aligned double-jambed trapezoidal doorways at Huánuco Pampa, Peru, along the main walkway from the Inka ruler’s (Thupa Inka Yupanki) living quarters to the main plaza (Figure 2). This paper will investigate the reasons the Inka may have constructed such frames, positing politico-religious functions that directed one’s gaze to the sacred or elite, protected or segregated the viewer and/or reinforced power relations between human and sacred realms.

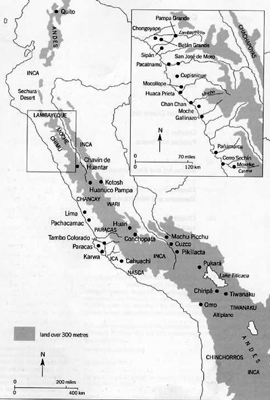

The Inka region of the Andes, located along the western coast of South America, consists of what is today northern Chile, Argentina, Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador (Map 1). Approximately 2,500 miles long but only 300 miles wide, this is a land of extremes. Here, one finds the longest and second highest mountain chain in the world, some of the world’s driest coastal deserts and dense tropical jungles. Distinct ecological zones, each producing its own set of goods and crops are packed so tightly together that in some areas several zones can be reached within one day’s walk.[1] Additionally, the Western Andes is prone to earthquakes, mudslides, flash floods and other natural disasters, making it a very difficult place to settle. Using political acumen and warfare, the Inka subjugated this large and culturally diverse area in only about one hundred years (c. 1430 - 1532) but were themselves conquered by the Spanish by the mid-sixteenth century.

People in the Andes adapted unique strategies for survival well before the rise of the Inka empire. Archaeologists have found evidence of complex reciprocal trade relationships dating as far back as c. 2500 BC through midden and grave remains that originated from a variety of climactic zones. Dualistic imagery, seemingly stemming from this intense reciprocity, is commonly seen in even the earliest art forms of the Andes.[2] Reciprocal relationships, however, were not limited to people. Andean cosmology featured an animate and sacred landscape full of deities that demanded worship and offerings in exchange for such necessities as water, abundant crops and good health. Although early Andean culture did not employ an alphabetic writing system, scholars have found evidence of these reciprocal attitudes in artistic iconography. Early vessels, such as one Moche pot depicting an anthropomorphized mountain dripping with the blood of sacrificial victims, for example, illustrate Andean beliefs in reciprocity between deities and humans—in this case illustrating human sacrifices to mountain deities in return for abundant rain.

Written records from the early Conquest and Colonial periods (c. 1532 – 1650) also illustrate the close relationship between cosmology and the environment. Though incorporating the various motives and biases of their authors, these works, written mainly in Spanish or in a combination of Quechua (Inka language) and Spanish, provide invaluable primary data, particularly regarding Inka religious practices and politics.[3] We know, for example, that the Inka believed in many gods that resided in or comprised the natural world. These deities were responsible for providing water and bountiful crops but could also cause such disasters as droughts, floods and earthquakes, if not venerated properly. Among the main deities were Viracocha, the Creator god, Inti, the Sun god, and Ilyap’a, the god of Thunder.[4] The ruler was believed to be the divine son of Inti and, as such, was both a political and sacred symbol.[5] Powerful warriors and highly effective negotiators, Inka rulers mobilized thousands of people to build vast road systems and state structures that altered the landscape. Not only did these constructions help facilitate state business but they served as visual reminders to the people of those who had political control. Similarly, frames as part of Inka elite constructions, likely pointed to the sacred while serving to remind one of the political power of those who put the frames in place. But could there have been other reasons for the frames? To explore the various possibilities of meaning of the frame, it is helpful to understand the significance of the “subject” being framed. Whether that which is framed is an object, a particular feature of the landscape or an elite personage, the very act of framing creates a relationship between subject and viewer. The choice of material used for both frame and framed may have also held significance to the Inka who held special regard for certain animate and inanimate objects. Stones, for example, played particularly important roles in Inka belief systems as they could be called suddenly to action to help their human counterparts, even turning into humans themselves. One story recounts rocks on a battlefield rising up as warriors at a particularly perilous moment in the fight to help the Inka soldiers defeat their enemy.[6] According to Susan Niles, “Origin myths tell of founding ancestors emerging from the earth, being converted to stone, and remaining for all time as tangible proof of the story.”[7] Rebecca Stone-Miller writes:

Natural-looking boulders are the most frequent objects set within borders, while all extant Inka frames are made of rock. This may be an issue of preservation, however, as stone does not disintegrate as easily or quickly as organic materials, possibly distorting the surviving sample. Other factors may distort the data surrounding frames as well. There is no way of comparing how many frames were originally created to those that remain since natural phenomena and later human activity may have disrupted the placement of a frame. Another issue concerning the current framing sample lies in how some sites or features within these sites were later reconstructed. Despite these questions, it is valuable to analyze the frames that remain as important clues regarding their meaning may emerge that can be corroborated with other material findings or with historical descriptions that further our understanding of Inka world views.

One of the most common types of Inka frames are the low-lying walls that surround boulders, such as with the “Sacred Rock” at Machu Picchu, Peru (Figure 3), located in the southern highlands. This site is striking for its location on top of a narrow mountain crag (Figure 4). The Sacred Rock was placed in the northern corner of Machu Picchu, visually near the taller peak of Huaynu Picchu to the north and the Yanantin mountain “behind” it to the northeast. (The “back” of the Sacred Rock faces almost due north.) At first glance the monument appears to be a large (approx. 12’ x 20’ x 3’) natural boulder surrounded by a low-lying (approx. 3’ x 25’ x 1 1/2’) rectangular wall made of smaller, rough stones. However, the boulder was subtly manipulated to mimic the surrounding mountains. While the Yanantin mountain is almost always cloud-covered, when the clouds are lifted, one can see that the stone and mountain behind it look strikingly similar.

Perhaps the Sacred Rock, then, was a way for the mountain to remain visible even when clouds mask the “real” mountain behind it. According to Johan Reinhard, mountain deities were particularly important to the Inka as they were responsible for providing rain and abundant crops. This is most likely why child mummies, sacrificed in special ceremonies, have been found on some of the highest mountain peaks in the Andes.[9] Identifying the significance of the Sacred Rock as a visual reminder, however, belies the pan-Andean tendency to emphasize an object’s essence rather than outward appearance. As Rebecca Stone-Miller has pointed out, this concept of essence explains why the Nazca Lines were too large to have been seen from the ground or why Inka and other Andean goldsmiths sometimes masked precious metals with pigment or other materials.[10] But if the signficance of the Sacred Rock was not to replace the hidden mountain, what other function could it have had? Perhaps another pan-Andean concept is applicable here--reciprocity. Given the emphasis on reciprocal relationships between communities and between people and gods, it seems reasonable that Andean artists wanted to create a monument that would illustrate the reciprocal relationship between humans and mountain deities. “Mountain stones,” such as the Sacred Rock, litter the site of Machu Picchu but none come close to its scale, and none other is framed. Why did the Inka artisans go to the trouble, then, of constructing this surrounding wall, particularly in the rugged terrain of a site like Machu Picchu? Could it have been a purely decorative choice? While this is possible, it is not likely as there are no other Inka examples of “mere aesthetics” and no mention of the concept of art as it exists in the West in any of the post-Conquest texts. The presence of the low-lying wall seems to point to the special character of the Sacred Rock itself. Perhaps it marks a special visual dialogue between stone and mountain,[11] or was produced as a way of commemorating the supernatural mountain to bring it into the human realm, and vice versa. The wall also sets up a visual boundary between viewer and rock. Perhaps the stone wall was used as a means of keeping people at a distance from a particularly powerful object or was a marker of the extremely sacred. Sacred places, beings or objects called huacas dotted the Inka landscape. These huacas took on many forms including springs, mountain peaks and rocks and facilitated communication with the supernatural world.[12] As such, they would have served as powerful mediators between the supernatural and natural, making it too dangerous for ordinary people to touch them. Frames around these powerful objects may have protected or reminded the viewer not to get too close.

Another common type of framing seen in the Inka region is exemplified at Machu Picchu in the Semi-circular Temple (Figure 5) where, again, one can observe what appears to be a large, natural outcrop surrounded by a stone framing device. In this case, the finely cut walls of the D-shaped structure curve around the embedded boulder which has been subtly manipulated to mark an astronomical alignment. A window opening, located on the curved wall faces northeast and was oriented toward the Pleaides rise azimuth (65°) during the fifteenth century.[13] Upon the rising of the sun at the June Solstice, the sun’s rays would have lined up with an edge cut into the stone.[14] In this structure, then, framing takes on multivalent functions. Not only would the entire structure have acted as a border for the rock outcrop, but the window located in the curved wall would have framed the astronomical phenomenon that occurred annually at this spot.

Window openings may have also served as frames for particular spots on the landscape. Susan Niles states that the “Inka repertory of forms includes viewing platforms, thrones and fenestrated walls oriented to frame prominent features of the landscape.”[15] Whereas Paternosto notes that windows facing east oftentimes “framed mountains that must have had a sacred character.”[16] One structure at Machu Picchu, “Temple of the Three Windows,” has three unusually large trapezoidal windows that face east (Figure 6). Not only do the openings direct one’s gaze to the Yanantin mountain to the east, but the presence of three windows may visually signal the recreation of an Inka origin myth. The Spanish chronicler, Sarmiento de Gamboa, relates that the birthplace of the first four Inkas was from three windows in the side of a hill, much like the structure at Machu Picchu.[17] The framing devices here, then, make an implicit connection between human observer, sacred landscape and Inka rulership. Just as with the “Sacred Rock,” the Intihuatana or “Hitching Post of the Sun,” appears to have been sculpturally manipulated to replicate the curvature of the mountain behind it (Figure 7). Located at the highest point of the main plaza area of Machu Picchu, it is visually framed by flanking structures. Although its function has not yet been determined, it may have served as a place to set offerings to the Sun or may have symbolized the “place spirit” of the mountain.[18] Whatever its function, it is clear from its high placement, mimicry of the surrounding mountains as well as the presence of framing devices that the Intihuatana was a very important monument. Another framing technique commonly employed by the Inka is serial doorwayor window alignment. While there are many examples of this type of alignment at Machu Picchu, Huánuco Pampa provides a particularly striking example. Huánuco Pampa is a well-preserved site located north of Machu Picchu on a flat plain high above the Urqumay River in Peru. The site covers an area of approximately 1.24 square miles and originally held approximately 4,000 structures.[19] Finely cut stone, associated with the elite, can only be seen in the eastern sector of buildings which is thought to have been a palace complex for the Inka ruler, Thupa Inka Yupanki.[20] It is in this elite sector that Inka artisans constructed a series of four trapezoidal, double-jambed doorways each aligned to frame the other as one looked from the main plaza toward the palace compound (Figure 2). These gateways would have traced a long east-west passageway connecting the main plaza to the ruler by framing him as he walked out of his palace toward the people gathered in the central plaza. The eastward direction traveled by the Inka as he arrived at the plaza, and the westward direction in which he returned, may have emphasized, together with the bordering elements, the ruler’s sacred and political power. The framing examples at Machu Picchu and Huánuco Pampa suggest that Inka artisans deliberately chose to frame certain objects through the strategic placement of stone or architectural elements. These examples point to functions that adhere to deeply ingrained Inka worldviews, namely reciprocity, politico-religious sanctity and the continuous dialogue between humans and the surrounding sacred landscape.

|

|||||||||||||||||