| PART | | Journal of the CUNY PhD Program in Art History |

|

|||||||||||

| In the 1960's in Paris, a group of artists calling themselves the Situationist International invented a term for their politicized explorations of the urban environment - psychogeography, which Guy Debord defines as “the study of the specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organized or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.”[1] This term refers to the psychological characteristics of landscape - the impression it makes on us, an impression affected and complicated by the landscape’s history and inhabitants. The SI left behind few physical traces of their experiments other than maps, texts, and some grainy photographs, but their critique of the spectacle inherent in consumer culture and their attempts to find a way to circumvent it in a real and personal interaction with the streets and population of Paris remains their artistic and political legacy.

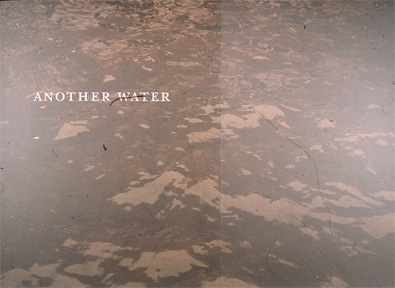

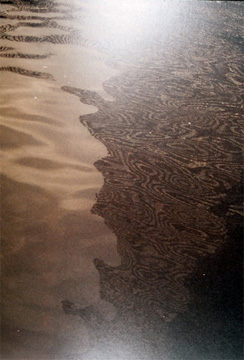

Although contemporary artist Roni Horn’s work does not bear any relation formally to the fragments left behind by the SI, in her absorbing work, Another Water (The River Thames, for Example) (2000), Horn creates the experience of a latter day psychogeography, one that maps the vicissitudes of our time in a beautiful and disturbing manner. Viewing Horn’s photographs and reading her text, the audience can travel on a psychogeographic journey that provides both a critique of and a solution to the deathly consumerism of contemporary culture. This work actually has two forms: Another Water (The River Thames, for Example) is the title of an artist's book while Still Water (The River Thames, for Example) refers to a series of exhibition photographs. The latter are sometimes shown in their entirety, as at SITE Santa Fe in 2000-2001, or in a smaller format; for example, only four were displayed in 2002 in the MoMA QNS Tempo show. The exhibition differs somewhat from the book in scale and aesthetic effect. The photographs in the exhibit consist of large close-ups of moving water (roughly 30 x 41 inches), and the images of water are speckled with footnotes which match numbers in the tiny black text running along the white "footer" just underneath the photograph [Fig. 1]. In the more intimately scaled paperback book, no footnotes appear on the surface of the water and each photograph is split by the central binding of the book. The paper is matte and unframed, and the photographs extend to the edges of the page except along the bottom. The footnotes begin on the cover and wrap around into the book itself, ending mid-sentence on the back cover, thus creating a book with no end. The pictorial form of the book is therefore consonant with its physical form; together they reinforce the visceral impression of the endlessly running river [Fig. 2].

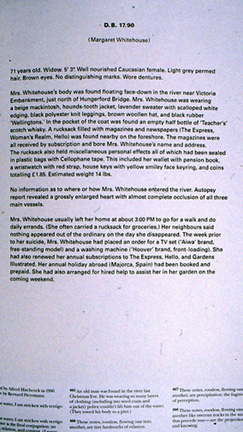

The flow of the book is interrupted, however, by seven texts describing suicides in the form of police reports or obituaries. Printed on the right side of the page, the paragraphs of text face the white, blank left side, in stark contrast to the photographs, creating a full stop in the otherwise seamless page-flipping [Fig. 3]. These documents of suicides add a fictional note, since it is hard to believe even the British police or newspapers are eccentric enough to report such details as: "lavender sweater with scalloped white edging, black polyester knit leggings." There is no citation anywhere in the publishing information acknowledging police reports or permission from newspapers, so it can probably be assumed that they are indeed falsified. This element was not present in the Tempo or SITE Santa Fe exhibitions, and changes the mood of the work. In fact, the obituaries make clear the subtext of Another Water: the attraction of the Thames River for suicides. Footnote: #397 reads: (Drowning is a more common suicide here than in the States. In the States it's mostly shooting. Maybe it's because you can't get guns here. But maybe it is also the quality of the water. It must be, because foreigners come to drown themselves in it).

Horn documents somewhat arbitrary factual and mostly impersonal information on the reports, so that the suicides are known only by their names, their personal effects and what they told the neighbors the week before. (Their motives or the effects of their actions are not mentioned, and Horn does not speculate about them - although the work as a whole can be considered an indirect speculation on the reason for their deaths). The most ordinary, normal-seeming people are documented in Another Water, as well as people in more unusual circumstances. Most striking perhaps is how prepared many of the suicides are - one man strapped his bike to his chest, other people taped their possessions to their bodies in cellophane bags. One particularly upsetting footnote (#158) describes a woman who drove her Ford Fiesta into the river with her Irish Setter, the windows closed, the door locked and the dog's leash wrapped around her hand. Horn’s apparently morbid interest in this facet of the river reflects her underlying theme - the question of meaningful existence in contemporary society. In the footnotes underneath the water, Horn refers to many American and British cultural and literary sources, including the poetry of Emily Dickinson and Wallace Stevens, the stories of Edgar Allen Poe, Raymond Carver, and Flannery O'Connor, the novels of James Joyce, William Faulkner, Joseph Conrad, and Charles Dickens. She usually quotes a line, such as "#47 (Between grief and nothing, I will take grief.)" which refers to "#48 From the novel The Wild Palms by William Faulkner, 1939." The text mentions numerous popular songs having to do with the river and death (Neil Young, Hank Williams, and The Temptations, to name a few), and various filmic moments, such as when the protagonist Alex considers suicide in A Clockwork Orange by Stanley Kubrick. Horn also refers to philosopher Martin Heidegger's 1967 essay "What is a thing?" [2], a meditation on the nature of existence. Critic Meg O'Rourke has commented that Horn's art "does not come out of a sculptural tradition so much as an intellectual history that philosophically embraces the world and its disciplines." [3] Horn's many references to other sources create a web of associations and meanings, cumulatively adding to the effect of her art by engaging with a vast cultural array of ideas. The unconventional use of footnotes in Another Water also recalls the fiction of David Foster Wallace, whose best selling 1996 novel Infinite Jest centers around a father's suicide. The notes lend an air of scholarly reassurance, functioning at times in a short series related by a theme which ends after a number of notes, and at others in discrete thoughts, such as "#4: Thinking about water is thinking about the future - or just a future" or "#93 It's hard to talk about water without talking about oneself." They refer to various historical and sociological aspects of the Thames, such as the "jumpers," Dead Man's Ledge (a place where bodies washed up in the nineteenth century before it was blocked), the many bridges, the pollution, and the birds. The importance of language and the appropriation of literary and other cultural sources has a history in Horn's work. After graduating from the Yale MFA program in 1978, the New York-based artist began her career making conceptual, machine-made metal sculptures, quickly moving to pieces using Emily Dickinson's poetry and quotes from Simone Weil. In the 1980's Horn exhibited drawings of sentences, made from cut and pasted fragments of letters, and in the 1990's she began to experiment with photography, creating a number of artist's books in the series To Place: Ísland. These works, which document geologic and social realities intrinsic only to Iceland, reveal Horn's interest in the specifics of geographic location, an aspect also present in The River Thames. Horn's Iceland series relies heavily on this "site-dependency," exploring various aspects of that country’s geologic oddities, such as its thermal waters or its unusual land formations, as metaphors for a primal, individual experience of nature. Horn has not moved away from geography nor geology in Another Water, but her photographs here disavow a specific sense of place, extending the idea of landscape into a psychogeographic terrain. She has cropped out any distinguishing features of the river, such as its banks and bridges, showing only close-ups of the water itself. The only reflection Horn ever captures in the river photographs are abstract patterns created by the rippled surface of the water. Usually, in walking along or looking at a river, as Horn invites us to imagine we are doing, one is aware of the surrounding environment; the weather, the shores, buildings, human and animal presence, the sound of the river. Horn mentions several of these elements - she compares the noise of the river to the sound of the trees in the park scene from the movie Blow-Up and she has several passages referring to the bridges ("So many bridges...invitingly scaled - a virtual forest" #645); but they remain external to the direct visual impact. Despite the increasing use of photography in

her work, Horn has said that she does not consider herself a

photographer per se. Her photographs usually rely on the indexical

nature of the photograph; the fact that this place or person

once existed and therefore that the photograph is a referent

of the real.[4] However, in Another Water, the coordinates

of time and space are absent, leaving the viewer to contemplate

a metaphor of universality. Although on the one hand Horn encourages us to imagine the sound of the river or the look of the bridges, she also asks us to view the photographs not as images of water but in their object-ness, as literal paper. Her text causes us to consider the notes not as a fictive narrative presented in its totality but as a possible site for interaction with the author: "What about this note? Do you like it?" asks footnote #287. "I could have moved it to another page, but that might have changed its content." Horn requires the viewer to become aware of his or her actions and interactions with the work, while calling up associations of other works and other ideas. Another Water takes Horn's use of photography and interest with text and literary and cultural references in a new direction from most of her previous work, which reviewers have called "austere and cerebral,"[5] or "laconic and seemingly hermetic." [6] But in Another Water, ideas jump to life and the viewer is almost overwhelmed by the intimate, confiding presence expressed through the text. The work speaks to us, as viewers; it engages us with questions and directs us with its syntax and references. Both text and photographs consciously play with the conventions of traditional writing and photography. Sometimes they are synchronized, producing together the effect of staring at water and letting one's thoughts run and drift. On other pages, the photographs contradict the text, such as when Horn discusses all of the "eensie, weensie" bodies of babies that must be in the Thames, creating the fantastic vision of a primordial soup. In contrast, the water appears clean, clear and entirely innocent. Horn also addresses the complexities of photography and her use of it in the text. A series of footnotes runs as follows: #124 This photograph is an image of a moment

on the Thames. It is also a moment similar to other moments

of moving water and especially moments of rapidly moving water

that were hardly visible...You feel like you've seen it before..

But you haven't, what you've actually seen is a slur: the form

a river often takes in real time. In these footnotes, Horn reminds the viewer to be aware of the representational capacity of photography by pointing out all of the aspects of a river that photography cannot represent: its temporal quality of constant change, its wetness and its motion. Through words, she reminds us of the quality of water's very "being," which can only be imagined and not actualized, reproducible neither by words nor by images. Critic Frances Richard has said of Horn's sculpture that it "grapples with the maddening and/or ecstatic drift that plagues representational systems, the tenuous connection between extant objects and their names or pictures." [7] The use of three means of representation in Another Water - written description, photography, and what appear to be official documents - shows Horn’s continued interest in the processes of representation and their meanings. The intersections of these systems move towards a more comprehensive effect of meaning. The numbered footnotes create a de-centered, flowing chain of thoughts; a system, but one that changes, revealing slight inconsistencies. For example, footnote #832 exactly repeats #285 except that the word "brownish" is substituted for "greenish." The whole text repeats itself several times but not in quite the same order, leaving the viewer to wonder, did I read this before? In relation to what? But this is a gentle disruption, only mildly disorienting. The photographs, which do not repeat (although they could and it would be difficult to tell) represent different moments in time on the river, revealed by their different colors, light and surface texture. Another Water brings predecessors to mind, such as Vija Celmins' Untitled (Ocean) (1970), a highly skilled graphite drawing of waves covering an entire sheet of paper. Another Water also suggests Felix Gonzalez-Torres's “stack” Untitled (1991), a roughly three by four foot rectangular pile of paper with the same black and white photograph of water printed on every sheet, and Lani Maestro's 1993 a book thick of ocean, which contains pages of photographs of water without edges or borders. Clearly there is something unique and mysterious about this image of endless water that lends itself to each work. Despite the similarity in imagery, however, these works are not repetitive. The different forms and media, and especially Horn’s inclusion of text, which the others lack, differentiates them. Horn’s friendship with Gonzalez-Torres - they made works for each other, such as Horn’s Gold Mats, Paired For Ross and Felix (1994-1995) and Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Placebo-Landscape for Roni) (1993) - makes the connection with death and repetition between Another Water and Gonazalez-Torres's stack particularly pertinent. Untitled (1991) is black and white, however, endlessly repeating the same, rather sinister image of black water, while Horn’s color photographs differ from each other, and her use of color gives the photographs a life and vibrancy not present in Gonzalez-Torres’s work. Yet another conceptually and visually similar

work is Andreas Gursky's digitally manipulated photograph of

the Rhine river, Rhine II (1999). But again, Horn’s

inclusion of chatty text gives this piece a markedly different

feel from the mute image of Gursky, and her visual contemplation

of the Thames, a river as significant for Anglo culture as the

Rhine is for German, is given a sense of passing time, motion

and multiplicity by her variety of photographs, at the same

time that her text evokes its more sinister qualities. I am convinced the Thames itself is partly responsible for the suicides that end up there...The river evinces intimacy and fear. It possesses a monumentality without scale, and its surface is at once transparent and opaque. I took thousands of images of it, and I have come to see it as the ultimate metaphor, a mirror for our rights and wrongs, a surface in which we see ourselves. [8] This mirror of rights and wrongs, in Horn's words, seems in fact only a mirror of wrongs - suicides, murders, pollution - unless one considers the stunning beauty of the photographs. Susan Sontag has said "So successful has been the camera's role in beautifying the world that photographs, rather than the world, have become the standard of the beautiful."[9] Often photographs of ordinary or ugly places can display a composed beauty through the artifice of the photographer, and this collection of photographs, through being cropped of any landmarks and through close-up and careful attention to light, surface, and pattern, attends to this ability of the camera to create beauty where possibly none existed. Despite the sometimes strange, gelatinous textures and murky colors, the photographs seem to glow; it is clear that of the thousands of images Horn took, she used the most striking in this work. The landscape that Horn evokes in her text runs in an uneasy counterpoint to the striking visual beauty of her photographs. Hardly a landscape in the traditional sense, eschewing all visual representations of buildings, countryside, and people, Horn's text instead reminds us of the psychogeography of place, the panoramic combination of history, breaking news, trivia, cultural influences, and passing ephemera that accompany a personal and solitary experience of an actual landscape. That Horn hopes to portray such a psychogeography of contemporary culture can be seen in her peculiarly modern understanding of her subject. She acknowledges her postmodern style - the appropriation of other sources, usage of mixed media, and deconstructivist tendencies - in the wry footnote, "We should recognize that contemporary water is mostly a parody of waters past;" but this irony extends not only to her style but her view of death. All of Horn's references, other than her brief mention of Swift (not footnoted), are taken from literature, songs, films and philosophy of the mid-nineteenth to twentieth centuries. The earliest is a Poe short story dating from 1841. This seems less than coincidental if one considers possible works Horn does not cite - Hamlet, for instance, with Ophelia's drowning and Hamlet's constant, morbid preoccupation with ghosts, vengeance and death, seems at first an appropriate source to include in Another Water. But the noble tragedy of Shakespeare is antithetical to the modern, ironic attitude expressed by Horn. The suicides in Another Water are haunting precisely because their tragedy lies in the banality and everydayness of their lives and their existence in a consumer culture. They were ordinary men and women who subscribed to Hello, rode mountain bikes, and drove Ford Fiestas. Such references in Another Water to brand names reveals Horn’s view of consumerism. She says: My work is in part a critique of the ways, so pervasive in the television and entertainment industries, of placing the viewer in a passive relationship to the world. This cultivation of passivity is a by-product of the domestication of technology. It gives me the sense that America is dying of entertainment - dying of lack of contact or dialogue. [10] To combat this passive, banal death decreed

by popular culture, Horn actively invokes a dialogue with the

viewer by addressing the viewer through text - and also by introducing

the topic of suicide, the presence of death as the choice of

an individual. Horn’s documentation of these supposed

suicides in intimate detail provides an indictment of popular

culture and its unthinking fascination with goods that are supposed

to provide happiness. I console myself with the horror of it...I try to visualize the viruses and bacteria as well, like hepatitis and e coli and the little bacteria of dysentery and cholera and that disease called Weils and, who knows, maybe a remnant of the plague, just lingering the way things tend to do near water. The pleasure of gaining new information, of connecting literary works, or of following a surprising train of thought or experiencing an amusing insight, together with the sinister beauty of the photographs, subverts the morbidity of the work. The underlying point of Horn's correlation of the suicides of the Thames with her ontological interest represented by the river as a metaphor is revealed in the Heidegger essay that Horn cites. For Heidegger, a person is defined only by his or her death, because only at death is a person’s life essentially completed. Horn focuses specifically on suicides because they throw the question of being into high relief. In their choice to die, suicides make especially vivid the philosophical correspondence between being and death. And it is precisely the question of being, of contemporary existence in its meaning, its illnesses, its pollution, its proximity to death, and yet its ability for pleasure despite this, through literature and culture, which Horn examines.

The formal aspects of the book create a contemplative state in the reader in order to accomplish this philosophical journey. If "(The Thames is us)" (footnote # 215); this river full of bodies, sewage, heavy metals, diseases, attracting suicides from near and faraway places, then Horn does not evince much optimism for contemporary society. But despite its morbidity, Another Water remains a visually striking, even pleasureable, work. Horn points to the answer to this contradiction in footnote # 86: "The possibility of poeticizing it - is that part of the human condition? - to ameliorate something awful." Her response to the deathliness of popular and consumer culture, and to our finitude (death as the limit of our lives), is to create a psychogeographic journey - to poeticize what cannot be avoided, engaging the viewer in a fascinating and poignant quest for the possibilities of existence [Fig. 4]. |

|||||||||||