| PART | | Journal of the CUNY PhD Program in Art History |

|

|||||

| During the nineteenth century there was an increased international interest in the work of seventeenth-century Dutch landscapists. This sparked many Dutch artists to develop a new appreciation for their artistic heritage, particularly landscapes. This genre of painting was revitalized in the work of Hague School artists such as Anton Mauve and Jacob Maris. In works like Mauve's Changing Pasture (1880's) these artists celebrated Holland's rich, agrarian past. Both their seventeenth-century predecessors and the French Barbizon School influenced these artists. The Hague School used a muted color palette similar to earlier Dutch artists. The group used a naturalistic style similar to the Barbizon School, but gave their subjects a more sentimental feeling.[1] It was against this backdrop of renewed artistic ferment that the young Vincent van Gogh found part of his inspiration to become an artist. Van Gogh wrote of his admiration for the Hague School, particularly its artists’ ability to capture nature on canvas. He commented, “A picture by Mauve, Maris, or Israëls says more, and says it more clearly than nature herself.” [2] This love of nature and peasant life also had its roots in his early childhood. His father, Theodorus van Gogh, had been a minister in the Groningen sect of the Dutch Reformed Church, whose members celebrated God's divine presence in the natural world.[3] Evidence of this is found in Van Gogh's own writings. Van Gogh reminisced about his childhood love of nature: “Has everybody been thoughtful as a child, has everyone who has seen them really loved the heath, fields, meadow, woods.”[4] After several failed attempts at various careers, in 1883 Van Gogh returned home to the Netherlands in 1883, where he decided to become an artist. Here he depicted the Dutch countryside of Drenthe. He felt that the land had a timeless quality, which harkened back to a purer, simpler time before the rise of modern industrialization. He wrote, “If you come to the remote back county of Drenthe…you will feel as if you lived in the time of Van Goyen, Ruisdael…such natural surroundings…roused in the heart…something of that free, cheerful spirit of former times.”[5] He felt that his depictions of the countryside linked him to the great Dutch masters of the past. During this period, Van Gogh continued his artistic exploration of the nobility of peasant labor and its connection with the sanctity of work and the land. This was accomplished through his depiction of the weavers in the village of Nuenen, as seen in his Weaver with a View of Nuenen Tower (1884). Van Gogh depicts the weaver actively working at his loom. Through the open window, we can see the countryside, with a woman picking crops and a church steeple in the distance. Here he depicts all the things that he values: the dignity of manual labor (as seen in the weaver working on the mechanical loom) and the importance of one who labors close to nature (represented by the woman toiling in the field). All this takes place in the presence of God, symbolized by the church steeple in the distance. The presence of the steeple also links the painting visually with the landscape works of his Dutch predecessors. The symbolism of this painting is similar, in certain respects, to images such as Jacob van Ruisdael's View of Haarlem with Bleaching Grounds (1665)[6]. It was also during this period that Van Gogh began to work with a perspective frame. The frame had strings that ran through its center. They were used to line up the landscape so the artist could paint it. Debora Silverman has pointed out that Van Gogh came to associate his frame with that of the weavers. He had been taught to think of painting as a craft by his secondary school teacher, Constantijn Huysmans. Silverman argues that Van Gogh thought of himself as a painter-artisan, weaving his paintings with his perspective frame.[7] At the same time, Van Gogh was also developing

his own color theories. He based them on the complementary color

theories of Michel Chevreul, director of the Gobelins Tapestry

Works.[8] Inspired by Chevreul's work in the weaving industry,

Van Gogh kept a box of colored yarn, which he used as a complementary

color palette. In addition, Van Gogh thickened his brush stroke

in order to give his paintings the feeling of woven cloth.[9] In 1888, growing weary of the hectic city life in Paris, he moved to Arles, a small town in the South of France. It reminded him of his home in Holland. Van Gogh wrote that the landscape was “exactly like Holland in character.”[11] In Arles, he returned to two of his major subjects: the peasant and the landscape. While in Arles, Van Gogh was joined by his friend Paul Gauguin. They worked together for two months, but tensions soon arose, resulting in Van Gogh's mental breakdown.[12] In May 1889, Van Gogh, realizing that he could no longer live on his own, and voluntarily checked himself into the asylum of St. Paul-de-Mausole in St. Rémy de Provence. While at the hospital, Van Gogh continued to paint, at times in the surrounding countryside. He also painted the view from his hospital room. He was particularly fascinated by the stars of the early morning sky. This article will examine Van Gogh's most famous star filled image, Starry Night (1889).

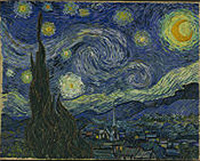

Van Gogh's painting gives us a utopian depiction of a small, picturesque village seen from a distance. Its most prominent building is its church, which dominates the center of the hamlet with its tall, thin spire. The small community is nestled in what appears to be the Provencal countryside near the asylum. In the background are the rugged Alpilles Mountains. A twisted cypress tree dominates the foreground, to the left of the village. The presence of the native cypress and the distant Alpilles both help identify this landscape as the one near the asylum. However, the most striking feature of the image is its dramatically rendered, star-filled evening sky. It contains eleven stars, whose blazing auras illuminate the heavens. The brightest star is located near the horizon, just to the right of the cypress. In the upper right corner, we see a crescent moon whose aura also illuminates the image. The central portion of the sky is dominated by a swirling wave-like pattern. Lastly, we see another undulating pattern, in the lower portion of the sky, running just above the hills. Most scholars have pointed out that the scene is imaginary. It has its roots in the Provencal landscape around St. Rémy, in Van Gogh's Dutch homeland and perhaps even in literature, specifically, the work of George Eliot.[13] Van Gogh placed a Dutch church from his childhood memory in his St. Rémy landscape. The landscape, minus the village, was visible from his cell window. Here we see Gauguin's influence on the artist. He had encouraged Van Gogh to paint from his imagination.[14] Because Van Gogh's cell was located on the second floor, he gave the painting a high vantage point. The presence of the Alpilles Mountains confirms an easterly view.[15] Scholars have deduced that the cypress was also visible from his room, based on an old advertisement for the asylum.[16] The painting looks as though it was viewed through the artist's cell window. Deborah Silverman has pointed out that during his Nuenen period, Van Gogh would use a window as a substitute for his perspective frame.[17] This is confirmed by the artist. He wrote, in May 1889, “ through the iron barred window, I see a square field of wheat in an enclosure, a perspective like a Van Goyen, above which I can see the sunrising.”[18] The view from Van Gogh's cell window may be seen here. Silverman also felt that Van Gogh's use of the perspective frame had symbolic religious significance linked to one of his favorite books, John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress (1678). In the book, Bunyan used the idea of a spyglass as a metaphoric tool for spiritual focus. Silverman believed Van Gogh thought of his perspective frame as a spyglass which he used to create his paintings.[19] This idea was confirmed by the artist when he wrote, “I think you can imagine how delightful it is to turn this spy-hole frame on the sea or on the snowy fields in winter.”[20] With this in mind, Van Gogh may have wished the viewer of Starry Night to see the landscape as he did, through his window, like a perspective-frame spyglass; focused on the church, the symbol of the heavenly city of Jerusalem. The painting's high vantage point, panoramic view with its large expanse of sky, and distant church link it visually with artists of both The Hague School and the seventeenth century Dutch landscapists. Van Gogh similarly used dual perspective points, created by the cypress in the foreground and the church steeple in the distance.[21] This use of perspectival distance might also have deep religious significance. The far-off church often represents the heavenly city of Jerusalem in seventeenth-century landscape painting.[22] It probably serves a similar function here. The church is Dutch in style with a pointed steeple. The actual church of St. Martin in St. Rémy had a dome and was not visible from Van Gogh's cell.[23] The depiction of a Dutch church and Dutch formal elements such as the foregrounded tree is also symbolic of Van Gogh's wish to return home during this stressful time in the asylum. On numerous occasions, Van Gogh wrote that he wished to “return north.”[24] The cypress in the foreground may also serve a dual function, both compositional and symbolic.[25] The tree, like the church steeple, is used to guide our eyes upward to look at the stars. To Van Gogh, the cypress had a deeper spiritual meaning. In his letter, he referred to these trees as “funeral cypresses.”[26] Around the Mediterranean, cypresses were planted in cemeteries. Ancient peoples also considered them symbols of immortality because of their long life.[27] The blackish green color of these trees also holds a similar meaning.[28] Van Gogh's flame-like treatment of the tree branches gives one the sensation that it is on fire. Fire has often been associated with rebirth or immortality. As a phoenix was reborn from fire, and then ascended skyward, so too, the flame-like branches of the cypress rise heavenward in the painting, suggesting immortality.[29] Van Gogh said that the trees reminded him of “line and proportion like that of an Egyptian obelisk.”[30] He knew of the obelisk’s association with the life-giving powers of the Egyptian Sun God, Ra. The obelisk represented the sun's rays and Van Gogh had referred to the Provencal sun as “the good god sun.”[31] Van Gogh's choice of the cypress can also be understood as a way to celebrate the specificity of the Provencal landscape. The cypress, like the olive tree (another favorite subject during this period), was native to the region. Possibly, Van Gogh identified with these hearty trees, which could survive in the harsh terrain around the asylum. In the past, he had referred to himself as “course” and “rough”[32], both words that can be used to describe these trees. However, the main focus of the work is the heavenly bodies that fill the night sky. Scholars have attempted to identify the stars. The star lowest to the horizon is Venus, the Morning Star.[33] This is corroborated by Van Gogh, who wrote, “This morning I saw the country from my window a long time before sunrise with nothing but the Morning Star.”[34] The same scholars have also debated over the identification of the other stars.[35] Like the rest of the elements in the work,

the stars had a spiritual meaning. Since he was a young boy,

Van Gogh had a deep fascination with the night sky. Based on

believes of the Groningen sect he learned as a child, he associated

the celestial bodies with the divine presence of God in the

world.[36] Even after he became disenchanted with organized

religion, Van Gogh still felt the spiritual pull of the stars.

He wrote in 1888, "[when] I have the terrible need of I

dare say religion…then I go outside at night and paint

the stars.”[37] The painting may also be connected to the poet Walt Whitman's book Leaves of Grass (1855). Excerpts from the book were available in French in 1888; including poems from a section entitled “From Noon to Starry Night.”[39] Whitman and Van Gogh had a similar ideological outlook. Both believed in the presence of the divine in nature and celebrated it in their work. Each man rejected organized religion. They also had similar tastes in literature and art. Both read Dickens and Michelet and loved the paintings of Millet. In an 1888 letter, Van Gogh wrote of his admiration for Whitman's work.[40] In Starry Night, Van Gogh captured the essential character of Whitman's work. In his poetry, there are numerous references to stars with their connection to the spiritual and the eternal. For both men, stars symbolized immortality.[41] Like Van Gogh, Whitman had a particular fascination with Venus, the “Morning Star.”[42] Van Gogh noted seeing the “Morning Star” from his cell window on several occasions. He wrote of his association between the soul’s survival among the stars after death. He put down these thoughts in a letter, wondering, “Perhaps death is not the hardest thing in a painter's life…But looking at the stars makes me dream. Why shouldn't the shining dots of the sky be as accessible as the black dots on the map of France? Just as we take a train—we take death to reach a star.”[43] The connection between Van Gogh and Whitman goes beyond the stars and their symbolic meaning. In other poems, such as “Weave In, My Hardy Life,” Whitman used weaving imagery to celebrate the creative life force in the world and in humanity. This type of imagery would have had great appeal for Van Gogh. He often depicted scenes celebrating the nobility of manual labor.[44] He would have also been interested in the weaving imagery for he thought of his canvases as tapestries interwoven with color. Also appearing high up in the heavens is the moon, which is clearly visible among the stars. Its depiction as a crescent also comes from Van Gogh's imagination. The moon was actually in a gibbous phase when the painting was created.[45] Like the stars, it too is steeped in symbolism. Van Gogh repeatedly used the crescent moon in his work.[46] It was a personal symbol of consolation. As a young man, he drew a crescent moon on a page of his Psalm book. The verse next to it speaks of spiritual hope.[47] The moon may also refer to a passage from the “Book of Revelations.” Meyer Schapiro saw the moon embracing the sun in the painting. He believed that the image may refer to a passage from “Revelations xii” which describes the appearance of “a woman clothed with the sun and the moon under her feet and upon her head she wore a crown of twelve stars”.[48] If Schapiro is correct, the painting is to be read as one with apocalyptic overtones, not spiritual exultation, or consolation, which is more likely the case. To the left of the moon is a large wave-like pattern. There has been much speculation as to its true meaning. It could be identified as a spiral galaxy or a comet.[49] I, myself, would argue that the wave-like pattern might depict the strong Mistral winds that are native to the region. Van Gogh referred to them and the difficulty they created for him in his attempt to paint outside in the countryside.[50] Just below the wave, we see a long horizontal strip, which runs parallel along the horizon, following the shape of the mountains. This may represent the pre-dawn glow of the sunrise, since we know that the painting is focused in an easterly direction in the hours just before sunrise. Van Gogh used an extremely expressive brushstroke in order to create a strong sense of rhythm in the painting. Undulating wave-like and circular patterns appear throughout the work. The pattern starts in the foreground bushes as small ball-like shapes. It then begins to widen out into an undulating shape, to accentuate the flow of the mountains in the background. It is repeated again just above the mountains in the highlighted horizon. It continues upward through the background of the sky, blending into the central wave-like shape. This shape becomes particularly important to the design composition, for here is where the transition is made into the circular shapes repeated in the eleven stars and their auras as well as the moon and its outer glow. The horizontal movement is also felt in the roofs of the town buildings. This time the brushstrokes are more linear, to accent the geometry of the buildings. Contrasting the horizontality of the landscape and sky, are the vertical waves of the cypress branches and the sharply delineated church steeple. Van Gogh chose to outline most of the elements in his landscape, including the cypress. This ultimately helps distinguish the earthbound elements from the sky. Van Gogh's trend toward stylization in this work is based on his continued dialogue with Gauguin. He expressed his desire “to seek a style”. He wished to make it “more viral by deliberately drawing”.[51] He felt that this put him in a similar category with Gauguin because his linearity is reminiscent of his Synthetist technique. Van Gogh wrote that, through these new techniques, they wished to create a modern art that would give spiritual “consolation” without overt religious symbolism, thus creating an image, which captured the “purer nature of the countryside.”[52] However, Van Gogh's work is more expressive and filled with a dynamic energy than that of his compatriot. This affinity for quick, expressive brushwork also had its roots in his Dutch past. He had admired the spontaneous brushwork of Frans Hals. He wrote of his admiration for Hals, “I saw Frans Hals you know how enthusiastic I was about it…about painting in one stroke.”[53] The thick application of the paint in distinctive, linear strokes reminds one of woven cloth. Perhaps, this was a conscious choice by the artist because he thought of his paintings as being woven on his perspective frame or loom. Van Gogh referred to the application of his brushwork as being “interwoven with feeling”.[54] The strokes on the mountains remind one of tilled soil. Van Gogh liked to think of himself as a laborer or craftsman. He described how he painted as “plowing on my canvas as they do on their fields.”[55] Van Gogh's choice of the complementary color scheme served a similar function as the brushwork: expressing a feeling. Of the expressive potential of color, he wrote, “color suggests ardor, temperament, any kind of emotion.”[56] He believed that the dominant color scheme of cobalt blue and citron yellow had a direct connection to the divine. He described the feeling of the infinite that these colors gave him, in his description of his painting, The Poet Eugène Boch (1888). The artist explained, “I exaggerate the hair…pale citron yellow…I paint infinity, a plain background of the richest blue…and by this simple combination, the bright head against the rich blue background, which gets a mysterious effect, like a star in the sky in the depths of azure.”[57] Van Gogh's association of these colors with the divine had its roots in the work of Eugène Delacroix. Van Gogh greatly admired Delacroix's work as a colorist. He believed that, “By going the way of Delacroix…by color and a more spontaneous drawing…one could express the purer nature of the countryside.”[58] Delacroix had depicted the image of Christ in his painting, Christ Asleep During the Tempest (1853). He used the complementary color combination of citron yellow and a Prussian blue to express Christ's divinity. He used the yellow for Christ's halo and the blue to depict his cloak, which covered his head. Seeing this painting reinforced this color scheme's association with the divine.[59] This color scheme, combined with the expressive movement of the brushwork, gives the night sky a feeling of divine exultation. The circular strokes of citron yellow around the stars and moon give the illusion that these heavenly bodies vibrate with radiant energy. Van Gogh's expressive style placed him in the forefront of the Post-Impressionist movement.[60] Van Gogh's love of nature was one of the central themes of his life. This resulted in his creation of a body of work dedicated, in part, to the art of landscape painting. He associated the landscape with the presence of God in the world. This came out of his exposure to the Groningen School of Protestant theology of his childhood. Through this belief system, he came to value the importance of manual labor and the divinity of nature. He incorporated these themes into his work. During his hospitalization in St. Rémy, Van Gogh had time to reflect on his childhood in Holland and the values he held dear. This resulted in the creation of one of his most celebrated works, Starry Night, which embodied these principle beliefs. In this image, created partially from memory, we see a Dutch village under a star-filled sky, a veritable tapestry of stars, and a symbol of spiritual consolation. This tapestry of stars, created by this weaver of images, has inspired a similar sense of wonder in viewers for much of the twentieth century, and will continue to fascinate well into the new millennium. |

|||||