| PART | | Journal of the CUNY PhD Program in Art History |

| Pro

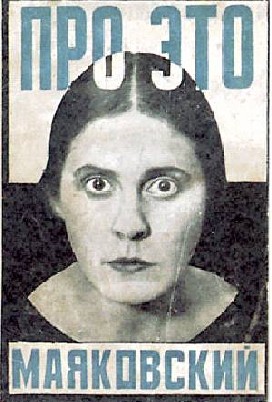

Eto: Mayakovsky and Rodchenko’s Groundbreaking Collaboration One of the great artistic talents of the twentieth century, Alexander Rodchenko produced innovative work in many fields: painting, sculpture, collage, photography and book, magazine, advertising and poster design. Published in 1923, the poem Pro Eto (About This), composed by Vladimir Mayakovsky with corresponding illustrations by Rodchenko, was the first Mayakovsky poem illustrated by the artist. Authorship of “constructivist Rodchenko” was announced at the beginning of the book, emphasizing the uniqueness and self-sufficiency of the illustrations. It was the first book in the history of art illustrated with photomontage. The montages were composed from cutouts of magazines and photographs, including those of Mayakovsky, Lili Brik, the woman he loved, and their contemporaries. Never before had images of the actual people described in a poem been used to illustrate it. Identical views and shared ideology turned Rodchenko and Mayakovsky into friends almost immediately after their first meeting in 1920.[1] Mayakovsky had a great respect and appreciation for Rodchenko’s style. In early 1923 they became close collaborators in advertisement production. The poet and the artist were also in contact as members of the Lef group, for which Rodchenko became the art editor of the magazine. It was not a coincidence that Mayakovsky asked Rodchenko to design and illustrate the publication of his recently finished poem. The complicated combination of artistic, social and personal reasons stands behind Rodchenko’s drastic shift to graphic design and to photomontage in 1923. Rodchenko had an extraordinary sensitivity to new ideas. Pro Eto’s illustrations were created with clear awareness of commercial advertising, photojournalism, Berlin Dada experiments and most importantly Russian avant-garde cinema. Pro Eto is a result of Rodchenko’s ability to synthesize and to invent.

This book is a true avant-garde manifestation yet at the same time it reflects the beginning of general depreciation of the avant-garde spirit. In 1923, changes in state politics concerning the arts, paralleled by changes in the art world itself, started to take place. The extreme aesthetic experiments of Rodchenko and his fellow artists were almost illegible for the general public. Enthusiasts of the new life and new culture, avant-garde artists moved into graphic design to stay connected to the new society that they strongly believed in. Parallel to that development, by 1923 easel painting and realism were restricted to only the state-approved artistic style. Soon it became so aggressive that photomontage, and later photography, would provide the only way to represent reality while avoiding the painterly realism.[2] For Mayakovsky and for Rodchenko Pro Eto was an attempt to hold their positions as avant-garde artists and to prove that there was a place for their vision in the changing society. Pro Eto is overloaded with historical significance. Yet no less importantly it is a work of art with remarkable aesthetic and conceptual quality. In this paper I will attempt to emphasize the highly original formal solutions and strong conceptual content of Rodchenko’s illustrations. I will point up how attentive the artist was to the ideas of the poet and how delicately he treated the controversial subject-matter of the poem.

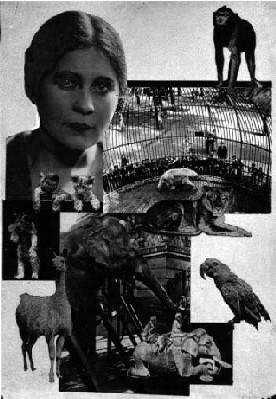

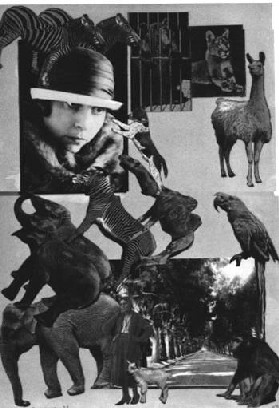

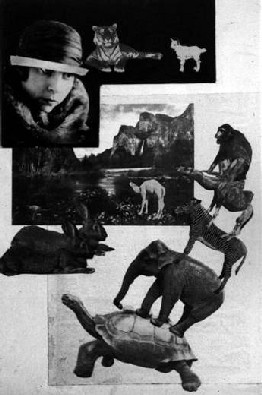

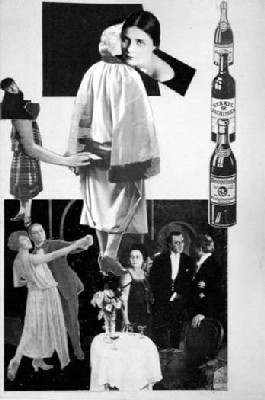

Vladimir Mayakovsky and Lili Brik are one of the most remarkable pairs of lovers in history and in literature. The role of Lili and her husband Osip Brik in Mayakovsky’s life has attracted the attention of serious scholars as well as scandalmongers. Osip Brik was the closest friend of the poet. The three of them lived together for almost ten years. Mayakovsky always called the Briks his family, and Lily his wife. For some their relationship is an example of corrupt morals; for others they represent a bold attempt to live by a new type of love and friendship. The poem was written during two-month separation of Mayakovsky from Lili Brik in the winter 1922-1923. The separation was her initiative, and was willfully accepted by the poet. The main suggested reasons for this were his jealousy and her preaching of free love. The poem expresses the troubled state of mind of the suffering poet. Although the personal relationships served as a lyrical springboard for the story, the poem was developed to deal with the universal problem of love and social relationships in the new Soviet society. Five years after the revolution, which Mayakovsky embraced with all his heart, came the New Economic Policy, and all that he had fought against seemed to be resurrected. The black-marketers, private entrepreneurs, and bureaucracy all affected the poet deeply.[3] For him the extreme privacy of the subject was the only language capable of expressing his universal questioning of the significance of life. Each photomontage is an illustration of a corresponding part of the poem presented as a complex kaleidoscope of its imagery, direct and indirect meanings, metaphors and suggestions. By condensing the compositional elements, Rodchenko captured the tension and the vivid ideas of the poem. The constructive arrangement of organic and inorganic, dynamic and static objects functions as a visual analysis of reality.[4] The montage component of photomontage is a means of destabilizing that reality and calling its legitimacy into question. Montage 8. Part III Application To… “Love” The theme of Love’s immunity to byt (Russian for “everyday life,” routine, inertia, philistine way of existence) and Love’s power to save the world is repeated throughout the illustrations. Last photomontage, Montage 8, is a pinnacle of the sequence of the illustrations leading to the culmination of the poem. Lily’s face at the top left corner dominates this montage. The line beneath reads: "It may, may be, some time, some day, along a pathway of the Gardens of the Zoo she too- for she loved animals- will also the Gardens re-enter/smiling like that photo in the desk of my room."[5] Mayakovsky actually kept on his desk a photograph of a smiling Lili, taken in the Berlin Zoo. Yet Rodchenko did not use this photograph, but another portrait of Lili in which she does not smile, preserving an ideal, romantic, even mysterious aura. This obvious contradiction of the text implies that Lili’s face functions not as the poet’s personal subject of affection, and not even as the heroine of the poem, but as a symbol of victorious image of Love for All, described in subsequent lines: "So that love won’t be a lackey there/ of livelihood, / wedlock, / lust/ or worse. / Decrying bed, / forsaking the fireside chair, / so that love shall flood the universe."[6]

It is remarkable that Rodchenko produced this montage in three versions. On one of these variants we find two portraits of Lili. The image of her wearing a hat and a furry coat is placed at the top of the page next to photographs of a bear and a lion. Another portrait at the bottom is superimposed on a large picture of a road receding into space, framed by straight rows of tall trees. The strong diagonal created by the road is paralleled by three diagonally-placed three rectangular pictures at the top of the page and by diagonally-positioned animal figures placed on top of each other at the middle. Attempting to stabilize the series of diagonals, the artist constructed a vertical line of images at the right edge of the page. A more successful whole was achieved in the second version. Here Rodchenko employed fewer figures. Intersecting planes of pictures animate the surface. Yet the unsupported pyramid of animals at the bottom of the page breaks the balance of the composition and destroys the well-composed arrangement at the top. Rodchenko obviously liked the idea of the animal pyramid. Possibly he was referring to the mythological belief that the earth is flat and rests on the backs of elephants which stand on a giant turtle swimming in an ocean that is the universe. In this case the pyramid of the animals symbolizes the superstitious, irrational and antiscientific old world, which will be destroyed in the future. Rodchenko changed the scheme completely in the published montage. The imagery is arranged in a carefully controlled way. Photographs taken from different angles and distances intersect each other in dynamic yet very balanced horovod, or circular dance, creating a unified and vibrant whole. Different compositional devices are actively employed by the artist. In this version, however, overlapping, diagonals, and contrasts are utilized in a more discrete manner. Their elegant and subtler character creates an atmosphere of harmony and substance. This peacefulness and stability reflects the utopian vision of the future expressed in the poem.

At the top of the montage Rodchenko placed a picture of a polar bear marching in his cage. The jealousy turned the hero into the bear earlier in the poem thus the bear in the cage symbolizes that there will be no jealousy in the future. He probably rejected the pictures of the receding road and the paradisiacal landscape as too sentimental. Showing different kinds of noble animals and utilizing the fact that animals are immune to human vice, Rodchenko successfully illustrated the poet’s prediction that in the future there will be no place for vulgar philistinism, no small-mindedness, no idleness. And finally, emerging from behind and dominating the whole is the image of Love, which for Mayakovsky was “the main thing.” Mayakovsky wrote: “My poetry, my actions, everything else stems from it. Love is the heart of everything.”[7] Nevertheless what looks like a “love poem” is in fact a poem about the search for a new self more consistent with ideals of the new society, a search for Love in its universal, all-embracing sense, Love for all and for everyone. As Feodor Dostoevsky believed that beauty would save the world, Mayakovsky believed that Love would do the same. Rodchenko’s imagery re-enforces the poem in which the poet dealt with the tension between personal affection, which is possessive, subject to jealousy and suffering, and Ideal Love, which is free and beautiful. The Controversial Aspects of the Illustrations A tormented personal love affair of the poet presented with astonishing sincerity within a poem was extremely controversial for that time. Rodchenko’s photomontage was an integral part of the poem; the opinion expressed regarding the written words was usually applied to the illustrations. During the period of Mayakovsky and Lili’s separation Rodchenko was in close contact with both. Not only did Rodchenko know the context of the poem’s creation, he also witnessed Lili and Mayakovsky’s relationships before the episode of separation. That placed him in a difficult situation. It gave him the advantage of a more personal understanding of the poem, yet it tested his impartiality. In all his montages Rodchenko carefully avoided any gossiping. It was known that during the separation Mayakovsky and Lili exchanged short notes. In fact on several occasions Rodchenko himself delivered those. In the poem there is a mentioning of the notes that connected the hero with his loved one. But Rodchenko rejected the version of Montage 5, where he himself is presented handing over a note to the heroine. In the accepted variant Rodchenko kept the self-portrait but presented himself as an inactive participant: a strange dancer on the background next to the partying group. Montage 5 is a disapproving comment on the artificiality and emptiness of bourgeois material culture. It presents the partying guests in the heroine’s apartment. They are the hero’s friends who forgot about revolution and spend their lives dancing and having empty conversations. Placing himself in the “friends” arena is a brilliant artistic statement clearly reflecting Rodchenko’s self-critique and his sharing of Mayakovsky’s vision expressed in the poem.

I think that among the reasons for Rodchenko’s doubts and production of the additional versions, the desire to eliminate the excessive directness of the references is important. In the first version of Montage 8, a picture of a dog reaching out for the Lili’s portrait crowns the top of the animal pyramid. Lili and Mayakovsky used to call each other Kisa and Schen (Kitten and Puppy).[8] Rodchenko, being a close friend, definitely knew about these nicknames. Thus the dog on the montage could be a metaphorical representation of the poet. Still, one cannot avoid thinking about the puppy-like character of his love. This version contains the image of a lioness placed at the top right corner, next to the picture of the caged bear. The bear refers to the poet’s transformation into the beast earlier in the poem. The lion is a big cat, so it could function as a continuance of the parallels to the nicknames, this time Lili’s. But it could also be a commentary on her relationship with the poet, which had a noble yet cruel character. This association is supported by the juxtaposition of Lili’s portrait at the bottom of this montage with the picture of a baby goat. The baby goat, a symbol of sacrifice, could refer to the sacrificial, altruistic love that will rule in the future. However it also could be perceived as a reference to the sacrificial love of the poet to the beautiful but too proud and independent Lili. It is possible that Rodchenko disliked the potential interpretation of this version in terms of the heroes’ actual personalities and relationships, in another version he avoids such direct references. At the top, unified by a black background, we find Lili’s portrait, a picture of a tiger, and a picture of a baby goat. In the context of the final scene of the poem it might be associated with the harmony and peace that will exist in the future. It also leads, however, to a predator-prey contrast, and the viewer might be tempted to see the combination of baby goat-tiger as a parallel to Mayakovsky and Lili’s relationship. In the published version, Rodchenko kept the image of a lion and added a picture of three lion cubs, but eliminated the image of the baby goat, thereby dismissing this predator-prey association. As mentioned before, one of the most controversial aspects of Rodchenko’s illustrations was the use of the photographs of the real people involved in the story. One of the most aggressive criticisms of Mayakovsky and Rodchenko’s work, in fact, came from Nickolay Chuzhak, the member of Lef. In his essay ”From Illusion to Materiality” (1925), Chuzhak blamed Rodchenko for imposing the naturalism of the poem on the reader by showing the poet himself as a hero.[9] He expressed harsh disapproval of the use of real places and real facts that in his opinion made the poem “weakly” personal and helpless because of these naturalistic qualities. However, Rodchenko’s use of real portraits demonstrates his interest in the documentary character of the image and belief in the relevancy and even necessity of documentary for the new society. The way these photographs were selected and presented clearly opposes Chuzhak’s statement.

Some of Lily’s photographs were taken from family albums. Rodchenko intentionally chose those in which she looks directly into the camera confronting the viewer. For almost all the portraits in which Mayakovsky has posed, his poses and expression clearly indicate his awareness of being portrayed. The “theatrical” character of the photographs opposes any voyeuristic suggestions. These portraits function as metaphors, as almost abstract elements. Their documentary quality is used to create a sense of surprise in the observer. This surprise forces the individual to call his reality into question and to suggest that since those are the real people represented, the reality described/depicted is also real. Rodchenko wrote: “The photograph of hungry people influences stronger than a drawing of them,”[10] and so, in the same manner, a picture of real people, struggling with inertia and philistinism, places the viewer directly into the reality of this struggle. Thus the reader is an intellectually active part of the poem. According to Sergey Eisenstein, the director and the theoretician of the Russian avant-garde cinema: “montage involves the creative process, the emotions and mind of the spectator. The spectator is compelled to proceed along the same creative path that the author traveled in creating the image (idea).”[11] Mayakovsky’s poetry demands the same effort from the reader. The illustrations for the poem are charged with seriously conceived symbolism and reveal how acutely Rodchenko was involved with the conceptual scheme of his illustrations. Rodchenko’s photomontages correspond to Mayakovsky style and undergird his images (hyperbolic, lyrical, emotive, satirical) with exceptional force. They represent one of the most successful examples of balanced relationships between illustration and text. It is indeed a product of the most fruitful collaboration between the poet and the artist.

Endnotes 1. Factually it was the second time that Rodchenko met Mayakovsky. Before he had seen him in Kazan’ in 1914, where Mayakovsky came with group of Futurists to spread Futurism. 2. Cristina Lodder, Russian Constructivism (New Haven, CT.: Yale University Press, 1983), 181. According to Lodder, the shift to photography gradually eroded the Constructivist principles which inspired it. Thus the photograph and photomontage were at once a symptom and a cause of the decline of Constructivism and of its interesting compromise with existing reality. However, it should be clarified that, while moving away from painting, Rodchenko successfully transferred the main principles of Constructivism into his design and photomontage. Emphasis on structure, clarity of forms, and the importance of factura remained the distinctive qualities of his works. 3. Herbert Marshall, Mayakovsky, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1965), 158. 4. This was pointed out by Lavrentev in Alexander Lavrentiev, Rakursy Rodchenko (Angles of Rodchenko), (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1992). 5. Marshall, 213. 6. Ibid, 214. 7. Bengt Jangfeldt, ed., Love is the Heart of Everything (New York: Grove Press, 1987), 33. 8 See Letters in Lili Brik, “Iz Vospomonani,” in Imia Etoy Teme Lyubov’ (The Name of This Theme is Love) (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1993). 9. Nikolay Chuzhak, “From Illusion to Materiality,” in Revisia Levogo Fronta (Revision of the Left Front) (Moscow: LEF, 1925), 115-6. 10. Leonid F Volkov-Lanit, Aleksandr Rodchenko Risuet, Fotografiruet, Sporit (Alexander Rodchenko Is Drawing, Photographing, Arguing) (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1969), 82. 11. Sergey Eisenstein, “Word and Image,” in Annette Michelson, “The Wings of Hypothesis: On Montage and the Theory of the Interval,” in Montage and Modern Life. 1919-1942, ed. M. Teitelbaum (Cambridge [Mass]: MIT Press, 1992), 63.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

© 2004 PART and Kristina Romanenka. All Rights Reserved.