| PART | | Journal of the CUNY PhD Program in Art History |

| The

Sublime Vision: Romanticism in the Photography of Albert Renger-Patzsch Albert Renger-Patzsch’s object-oriented work shares affinities with the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity or New Sobriety) style of realist painting that arose in Weimar Germany as a reaction against the spiritual and anti-bourgeois tendencies of pre-war Expressionism.[3] Although the term Neue Sachlichkeit is applied to an exceptionally diverse and geographically dispersed group of artists, Neue Sachlichkeit paintings, in general, are crisply focused, highly detailed, and often emotionally detached. Rarely, however, was Neue Sachlichkeit art purely naturalistic or objective; indeed, it is sometimes characterized as “magical realism,” a term that acknowledges the Romantic content apparent in some of the imagery. Though photography was touted as objective, photographers achieved visions of a “magical” or slightly off-kilter world through the employment of extreme angles, close-ups, tight cropping, and sharp focus.[4] In Albert Renger-Patzsch’s book of photographs Die Welt ist schön (The World is Beautiful), published in 1928, images of plants and panoramic landscapes appear alongside images of factories and machines. Taken in the Ruhr district, Germany’s most industrialized region at the time, the photographs decontextualize their subjects by emphasizing the shapes, surfaces, and formal similarities of disparate objects.[5] But although the region where Renger-Patzsch lived was home to heavy industry, the book by no means privileged industry over nature. Indeed, nature and industry appear opposed to each other in Renger-Patzsch’s photographs of the landscape and towns of the Ruhr district, some of which appeared in Die Welt ist schön. Far from presenting a “beautiful world,” these images depict the devastation of a once pristine agricultural environment by the factories and smokestacks looming on the horizon. These landscapes do not suggest the excitement of the Sublime, but rather, bring to the fore the old Romantic notion of the antagonism between city and countryside, particularly through their juxtaposition with the aesthetically enticing images of nature found elsewhere in the book.[6] And although Renger-Patzsch relied on a modernist formal language in his depictions of nature, his photographs of archetypal plants glorify nature in a way that recalls nineteenth-century Romantic paintings, in which artists infused the landscape with a sense of divinity. Caspar David Friedrich’s Cross in the Mountains of 1807-08 is a classic example. As demonstrated by Robert Rosenblum in his pioneering study, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko, Romanticism did not only capture the imagination of artists throughout Germany in the early nineteenth century, but persisted well into the twentieth century. The depiction of nature took on prime importance within the Romantic movement, becoming a surrogate for traditional Christian symbolism for artists disenchanted with the seemingly hollow rituals of the Church.[7] Early nineteenth-century Romantic painters, such as Caspar David Friedrich and Philippe Otto Runge, endowed nature with transcendental and divine qualities in their work. As a German artist employed in the art academy of Essen, Renger-Patzsch would have found it difficult to escape the legacy of Friedrich, Runge, and the scores of Symbolist and Expressionist artists who followed in the footsteps of the Romantics. Romantic artists wishing to express a sense of divinity within nature, and needing intellectual guidance, had turned to Edmund Burke’s influential treatise of 1756, Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful or the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and the Sublime of 1764 and Critique or Judgment of 1790. Collectively, these works emphasize the idea that a sublime landscape is one that inspires terror or awe—and simultaneous delight—through its sheer immensity and power.[8] For artists and philosophers of the pre-industrial Romantic age in Germany, natural phenomena such as waterfalls, gorges, and mountains became emblematic of the vastness and awesomeness of the Sublime. The experience of the Sublime was perceived of as a strongly emotional, or even religious, experience that could remind humans of their inconsequentiality in the face of nature’s power. Due to the pervasiveness of Romantic thought, this “cult of nature” was well established in Germany by the 1920s. Idealization of nature provided a foil to the urban utopia promised by modern technology and entertainment. During the Romantic era, the notion of spiritual communion with nature became a theme in painting, often through the use of the Sublime aesthetic. Later nineteenth-century social movements, such as nudism and vegetarianism, the youth movement,[9] and the development of garden suburbs, reinforced the notion that a life lived in close contact with nature was both physically and morally healthy. Indeed, the emphasis on industry and urbanism in Weimar culture can be misleading, as the majority of the population continued to reside in small towns and rural villages during the 1920s.[10] Nevertheless, industry and the metropolis were fast encroaching upon rural villages, as can be seen in Renger-Patzsch’s photographs of the Ruhr district. The reality of industrial development made his nature photography appear all the more sublime and fantastic. Writings by Burke and Kant, though obviously important for the development of Romantic aesthetics, were products of the Enlightenment. As such, they stress humanity’s psychological need to control the unknown and to devise rational ways of understanding the incomprehensibility of the Sublime. Edmund Burke, for example, argued that the Sublime was best contemplated from a distance. One could safely meditate upon the enormity of nature when it was presented in the form of a painting. The viewer could mentally enter the space of the painting and contemplate sublime nature while physically removed from it.[11] Regarding our reactions to the Sublime, Kant explained that when confronted with a sense of incomprehensible enormity or microscopic smallness, the viewer summons his or her mental powers of reason to rationalize and comprehend the previously unimaginable image or concept.[12] To facilitate the viewer’s comprehension of and delight in a sublime landscape, artists could impose a geometric order or other organizational structure—through perspective or other formal means—on the composition. The ability to suggest the irrationality of the world, while clearly controlling or domesticating it through visual means, would have continued to appeal to artists working within the sober, serious framework of Neue Sachlichkeit in the 1920s. Renger-Patzsch’s close-up photographs of nature exemplify the concept of the Sublime and our control of it through formal artistic means. He routinely puts the viewer face to face with defamiliarized, and even terrifying, images of nature. One such example, Natternkopf (Snake’s Head) of 1925 (fig. 1), is a photograph that evokes the Sublime within a modernist formal context. The snake is an archetypal emblem of danger, and the extreme close-up employed by Renger-Patzsch magnifies the sense of horror and danger as the viewer is directly confronted with the enlarged eye of the snake. Yet, through careful composition and close cropping, Renger-Patzsch simultaneously succeeds in transforming the snake’s coiled body into a geometric structure of concentric patterns; as the viewer becomes absorbed in the complex design created by the snake’s scales, the reptilian eye in the center of the image becomes less threatening. The snake seems simultaneously larger than life and under our control, as we mentally come to terms with the form of the image. Indeed, as Kari Elise Lokke suggests in her study of Kantian aesthetics, “it is possible to be impelled to an awareness of one’s superiority to physical nature, and to awaken to the sublimity of the human mind which is, according to Kant, beyond the sphere of nature.”[13]

For the Romantics, scrutiny of nature from a scientific angle was another method of visually exerting control over the potential chaos of the Sublime landscape. Romantic painters expressed a great interest in depicting nature faithfully and with scientific clarity. Indeed, Goethe considered scientific accuracy the key to the success of a landscape painting.[14] Yet in the work of artists like Runge and Friedrich, hyper-realistic, scientific rendering was nearly always a means of elevating nature to a mythical or larger-than-life status. For the German Romantics of the early nineteenth century, science had not yet acquired negative connotations based on its association with the dehumanizing effects of industry and the mechanization of society. Science was considered a humanistic endeavor, compatible with Romantic ideals in the early nineteenth century. The pursuit of knowledge for its own sake was valued, and science was seen as a useful aid to aesthetics. Photographers in the 1920s, of course, had witnessed how industry made possible the mechanized slaughter of World War I. Renger-Patzsch’s defamiliarized images of nature may well have functioned on one level as an attempt to reinvest the world with a sense of magical innocence.

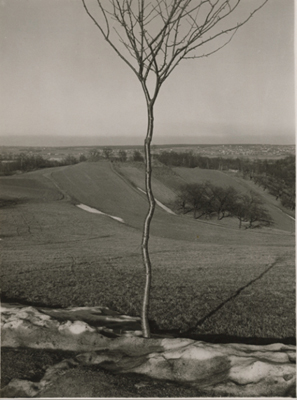

Trees took on great importance for Romantic artists, who presented them with scientific precision but also almost anthropomorphically, transforming them into expressive archetypes of nature. Like Snake’s Head, Renger-Patzsch’s photography of trees evokes the Sublime, partly through their compositional similarities to specific Romantic paintings. Das Bäumchen (The Little Tree) of 1929 (fig. 2) bears an unmistakable resemblance to Friedrich’s Der einsame Baum (The Lone Tree) of 1822, now in Schloß Charlottenburg in Berlin. Both the painting and the photograph present a single tree in the foreground, centered in the composition, clearly delineated, and sharply focused. Beyond each tree lies a vast landscape that stretches into the far distance, suggesting the sublimity of infinite space. Yet, in each image, our eye is continually drawn back to the foreground tree, which acts an as anchor in each composition so we are not overwhelmed by the vast landscape. Renger-Patzsch also photographed in the woods; in contrast to images such as The Little Tree, these photographs are small windows into hidden, enclosed spaces of dense vegetation. The evocative Woods in November of 1934 shows a cluster of silhouetted trees emerging from the leaf-carpeted forest floor. It is a scene of silence and mystery, removed from the realm of historical time. Its mood is similar to the gloomy, meditative atmosphere of works such as Friedrich’s The Abbey in the Oak Forest of 1810, a mysterious image in which bare trees frame a Gothic ruin. Both images fade into the mist, which veils the forest, allowing us to imagine it as endless and timeless. The romanticization of nature in Renger-Patzsch’s photographs, and his frequent emphasis on small fragments of nature, was described in the critic Carl Georg Heise’s 1928 preface to Die Welt ist schön. Heise explained that:

Thus, while the endless and the enormous reside at one end of the spectrum of the Sublime, microscopic smallness lies at the other. Highly detailed, quasi-scientific images of individual plants suggest this concept of incomprehensible minuteness. Romantic painters, in their careful renderings of plants, display empirical post-Enlightenment sensibilities, while also paying homage to their indigenous artistic heritage. German Romanticism revered the medieval and Renaissance culture of the Holy Roman Empire, and for Romantic artists, Albrecht Dürer and the landscapes by the sixteenth-century Danube School artists, such as Albrecht Altdorfer, had assumed an iconic status. Dürer’s carefully observed, magnified, and hyper-realistic studies of fragments of nature, such as the famous Great Piece of Turf of 1503, may have provided Romantic artists with inspiration in their quest to endow nature with spiritual vitality through faithful, scientific observation. For photographers, the view of the world through the camera lens illuminated details of nature that were inaccessible to the naked eye, yet they too drew on the model provided by Dürer. Renger-Patzsch made this clear in his 1925 essay Heretical Thoughts on Artistic Photography. He also expressed his preference for concentrating on small details of nature in this essay:

His obsession with these small fragments of nature was clearly articulated the previous year, in his essay, Photografieren von Blüten, in which Renger-Patzsch noted that to photograph plants and flowers, “one is forced to look, as it were, with the eyes of insects” in order to discover a microscopic world of “fantastic beauty.”[17]

Trained as a chemist, a “scientific” approach to the depiction of nature appealed to Renger-Patzsch. In his photographs, plants are often—as in Dürer’s studies—removed from their botanical context and set against a blank background, which both decontextualizes and aestheticizes them. Besides isolating the plants in this fashion, Renger-Patzsch severely cropped the images and used a sharp focus to illuminate the shape, textures, and patterned surfaces of the flowers with extraordinary clarity. In many examples, such as Sempervivum Tabulaeforme of 1922 (fig. 3), Renger-Patzsch employs such extreme enlarging and cropping that no background is visible at all. Instead, the surface of the flower fills the entire composition. Lacking context, the magnified image of the flower can initially disorient the viewer. The plant is defamiliarized and abstracted to the point where it is almost unrecognizable as a flower. Indeed, the patterning on its surface bears a distinct resemblance to the scales of the snake in Snake’s Head (fig. 1). This formalist, decontextualizing, aesthetic approach—characterized by the visual comparison of two disparate objects—exemplifies what Renger-Patzsch referred to as “joy before the object,” and also transports these images to the realm of the Sublime. The extreme enlargement of minute details of flowers, animals, and landscapes transcends the boundaries of easily observable reality in Renger-Patzsch’s images, forcing the viewer to rethink his or her visual preconceptions. These photographs allowed people to see fragments of nature that they could never have seen without the aid of modern technology. Within this modernist context, the camera became a tool for illustrating the Romantic notion of the Sublime. In the romantically-inclined words of Carl Georg Heise, the photographer (i.e. Renger-Patzsch) and his camera allowed ordinary people to “see anew the symbolism of the fullness of life itself, inexhaustible in all its parts.”[18] Although Renger-Patzsch may have originally conceived of these images within the spirit of scientific observation, they have thus become monumental archetypes of art and nature for their viewers and commentators. Michael Jennings writes of Renger-Patzsch’s plant photography that: “The intensity of these images, the glorification of the individual organic object, indeed, seems to lend to these plants a mythic status.”[19] Indeed, these images could illustrate Goethe’s notion of the Urpflanze, or archetypal organic prototype, from which he thought all organic development emanated.[20] Likewise, Romantic artists had depicted archetypal images of nature—rendered as scientifically as possible—in order to bestow a sense of divinity upon nature. In the “age of mechanical reproduction,”[21] as Walter Benjamin characterized Weimar culture, Albert Renger-Patzsch used the camera to present images of the Sublime with a modernist vision. The aesthetics of his Neue Sachlichkeit style were ostensibly realist, but ultimately had their roots in Romantic nature imagery. The Romantics, in turn, had looked to the detailed, hyper-realist style of Albrecht Dürer and the evocatively overgrown landscapes of the Danube School for inspiration. Photo historian Ute Eskildsen writes that Renger-Patzsch, despite his scientific background, described reality in metaphysical terms, “attributing to photography an extension of our vision and understanding because with its help we are able to perceive aspects of the natural world which are inaccessible to the naked eye.”[22] Photographers in the 1920s were not necessarily concerned with providing surrogates for Christian symbolism through the veneration of nature, but instead, wished to romanticize and venerate nature for its own sake, and to suggest the magical and inexplicable qualities of the natural world that had fascinated the Romantics. Influenced by the Romantic legacy as well as modernist formalism, Albert Renger-Patzsch turned to quasi-scientific observation—framing his observation with the aid of the camera’s lens—to emphasize the Sublime beauty of his subject matter.

Endnotes 1. See Abigail Solomon-Godeau’s essay, “The Armed Vision Disarmed: Radical Formalism from Weapon to Style,” in her book Photography at the Dock: Essays on Photographic History, Institutions, and Practices (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991): 52-84. Solomon-Godeau discusses the appropriation of Soviet Constructivist aesthetics by Bauhaus photographers, such as László Moholy-Nagy, who transformed the politically charged aesthetic of the Soviets into a formalist style that became emblematic of urban, capitalist modernity. 2. Thomas Janzen, “Photographing the ‘Essence of Things,’ in Albert Renger-Patzsch: Photographer of Objectivity, Ann Wilde, Jürgen Wilde, and Thomas Weski, eds. (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1998): 9. Renger-Patzsch’s career, in fact, culminated with the publication of two more books of nature photography in 1962 and 1966: Bäume (Trees) and Gestein (Rocks). 3. According to Jost Hermand, Neue Sachlichkeit represented an ideological viewpoint that rejected the spiritualism and idealism of artists and intellectuals in Wilhelmine Germany. The rise of an objective, almost photographic realist style in painting was, Hermand suggests, a response to the specific political, social, and economic concerns of Weimar Germany, a society in which middle-brow, bourgeois, consumer-oriented culture was becoming increasingly pervasive in the mid- to late-1920s. See: Jost Hermand, “Neue Sachlichkeit: Ideology, Lifestyle, or Artistic Movement?” in Dancing on the Volcano: Essays on the Culture of the Weimar Republic, Thomas W. Kniesche and Stephen Brockmann, eds. (Columbia, SC: Camden House, 1994): 57-67. The term Neue Sachlichkeit was coined in 1925 on the occasion of a large exhibition in Mannheim, which presented the work of post-war German realist painters. For general sources, see: Wieland Schmied, et al., Neue Sachlichkeit and German Realism of the Twenties (London: Hayward Gallery and the Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978) and Sergiusz Michalski, New Objectivity: Painting, Graphic Art and Photography in Weimar Germany 1919–1933 (Cologne: Taschen, 1994). Neue Sachlichkeit photography was exhibited in 1928 in Stuttgart in an exhibition entitled Film und Foto. See: Christopher Phillips, “Resurrecting Vision: European Photography Between the World Wars,” in The New Vision: Photography Between the World Wars, Maria Morris Hambourg and Christopher Phillips, eds. (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1989). 4. Herbert Molderings, “Urbanism and Technological Utopianism: Thoughts on the Photography of Neue Sachlichkeit and The Bauhaus,” in Germany: The New Photography 1927–33, David Mellor, ed. (London: The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978): 90. Mellor notes that “realism” or “objectivity” are not really appropriate terms for the photography of 1920s Germany, with its emphasis on stylized shots taken from airplanes and skyscrapers, and its focus on pattern and detail. 5. Many viewers admired Renger-Patzsch’s modernist-formalist approach to his subject matter, but Die Welt ist schön was harshly criticized by Marxist critic Walter Benjamin. Although Benjamin attacked Renger-Patzsch’s decontextualization of objects and aesthetic juxtaposition of unrelated images, his criticism was largely based on the book’s title, which he saw as reactionary. Ironically, it was Renger-Patzsch’s publisher who had insisted upon the title, correctly believing that it would appeal to the general consumer. Renger-Patzsch had wanted to call the volume Die Dinge (Things), a less subjective title. See: Ulrich Rüter, “The Reception of Albert Renger-Patzsch’s Die Welt ist schön.” History of Photography 21, no. 3 (Autumn 1997): 192. 6. For more information on the Ruhr landscape photographs of the 1920s, see Janzen, 15-16. 7. Robert Rosenblum, Modern Painting and the Northern Romantic Tradition: Friedrich to Rothko (New York: Icon Editions, 1975): 17. 8. Deniz Tekiner, Modern Art and the Romantic Vision (Lanham, NY; Oxford: University Press of America, 2000): 11-12. 9. The Wandervogel (Wandering Birds) was part of the German Youth Movement that arose around the turn of the twentieth century. This Berlin-based society organized long walks in the forests surrounding the city, to counteract the “unhealthy” effects of urbanization. 10. Michael Jennings, “Agriculture, Industry, and the Birth of the Photo-Essay in the Late Weimar Republic,” October 93 (Summer 2000): 26. 11. Tekiner, 15; Kari Elise Lokke, “The Role of Sublimity in the Development of Modernist Aesthetics,” The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 40 (Summer 1982): 421. 12. Iain Boyd Whyte, “The Sublime,” in The Romantic Spirit in German Art 1790–1990, Keith Hartley, ed. (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994): 139-140. 13. Lokke, 423. 14. Timothy F. Mitchell, Art and Science in German Landscape Painting 1770–1840 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992): 32. Mitchell argues that is was “no coincidence that the ‘Golden Age’ of geology shared with the developments of Romantic sensibilities the same half century—1780–1830.” (page 2). 15. Carl Georg Heise, “Preface to Die Welt ist schön,” (1928), reprinted in Albert Renger-Patzsch: 100 Photographs, 1928 (Cologne and Boston: Schürmann & Kicken, 1979): 11. 16. Albert Renger-Patzsch, “Heretical Thoughts on Artistic Photography,” (1925), History of Photography 21, no. 3 (Autumn 1997): 180. 17. Albert Renger-Patzsch, “Photografieren von Blüten,” (1924), quoted in Janzen, 9. 18. Carl Georg Heise, “Preface to Die Welt ist schön” (1928), quoted in Janzen, 13. 19. Jennings, 47. 20. Dorothea Dietrich, “Micro-Vision: Karl Blossfeldt’s Urformen der Kunst,” Art on Paper 3, no. 1 (September–October 1998): 38. 21. Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” (1936), reprinted in Photography in Print: Writings from 1816 to the Present, Vicki Goldberg, ed. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1981): 319-334. 22. Ute Eskildsen, “Photography and the Neue Sachlichkeit Movement,” in Germany: The New Photography 1927–33, David Mellor, ed. (London: The Arts Council of Great Britain, 1978): 103.

|

||||||||||||

© 2004 PART and Jenny McComas. All Rights Reserved.