| PART | | Journal of the CUNY PhD Program in Art History |

| Fascist-Surrealist

and Oedipal-Alchemical Identities in Max Ernst’s The Barbarians

Because of its title and date, Max Ernst’s 1937 The Barbarians, has been interpreted as a dream, or nightmare, image of fascism. Sabine Rewald, for instance, writes that the bird-creatures “symbolize the imminent danger from Hitler’s Germany,” citing John Russell’s 1967 biography of the artist.[1] Werner Spies and Diane Waldman have offered the same interpretation.[2] This fascist identity is bolstered by geographical aspects of the barbarian series—for example, the Barbarians Marching to the West of the same year, whose title defines the physical relationship between the Nazis and Max Ernst in Paris to the west. Indeed, all creatures in The Barbarians gaze, march, or point to the painting’s left, to the west, anticipating the literal blitzkrieg on the way.[3] Ernst himself confirmed all this in his comments about another painting in the same series: “The Angel of Hearth and Home… is of course an ironic title for a kind of juggernaut which crushes and destroys all that comes in its path. That was my impression at the time of what would probably happen in the world, and I was right.”[4]

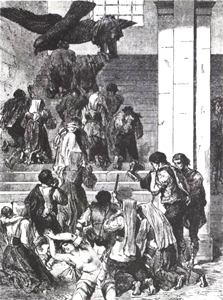

But the ‘barbarian’ identity of these painted creatures is not only horrific, as a caricature or dream-image of fascism, but also as one of heroic self-identification: a vision of the surrealist group. Such a union of opposites by means of a painted object is in line with Ernst’s occult obsessions, and as a surrealist identity, it can be traced back to the celebrated séances of 1922 [Fig. 2], which Ernst attended with Breton and Paul Eluard (although he himself never entered the deep trance state demonstrated by René Crevel, Benjamin Péret, and Robert Desnos [Fig. 3]).[5] During one of these séances, Desnos related a lengthy and detailed fantasy about a “great oriental army” that would come from the east to free the western world from itself.[6] For Desnos and his proto-surrealist coconspirators of 1922, these barbarians were like madmen: a force outside the hated zone of church and bourgeois morality, outside the authority of the Freudian father who had sent his sons to die in the trenches—like the unconscious mind itself an enormous untapped wellspring of liberation. In April 1925 Desnos’ barbarian fantasy was published in La Révolution surréaliste, under the title “Description d’une revolt prochaine.” Ernst was probably present at the birth-séance of these barbarians and, if not, would have almost certainly heard about them from Eluard, with whom he was living, or Breton, who was particularly impressed with Desnos’ lavish gift for mediumistic communication at a time when Breton himself was about to define surrealism as pure psychic automatism: “Desnos speaks Surrealist at will.”[7] Ernst had participated in séances earlier, in Cologne, when he and his friend Franz Henseler learned about the death of Franz Marc through the medium Macchab.[8] The mediumistic realm, linked as it was both to the occult and to a Freudian notion of the unconscious, was a regular source of Ernst’s inspiration, and in the early surrealist sky the psychic star of Robert Desnos burned very brightly indeed. Back then barbarians were seen as icons not of fascism but of the coming surrealist revolution.

Like much of Ernst’s pre-war painting, The Barbarians belongs to a series,[9] dated by most art historians back to The Horde of 1927 [Fig. 4] and said to include The Barbarians Marching Westward [Fig. 5] and The Angel of Hearth and Home [Fig. 6], both from 1937, and this double, or repressed, identity is present in this series from its inception. In fact, The Horde—dated by Russell, Waldman, and Rewald as the first painting in the series—was executed well before the rise of Hitler and the prevalence of antifascism as a surrealist concern. 1927 is a lot closer, in time as well as mood, to the heroes of “Description d’une revolt prochaine” than the monsters of German fascism. Furthermore, The Horde is a group of men, specifically, presented more or less parallel to the picture plane, which is unusual for Ernst, attuned as he was to sexual conflict and difference.[10] In fact, he only painted groups of men as ‘presentation’ pictures, which portrayed his surrealist cohorts in various guises. These include the famous Rendevous of Friends [Fig. 7], which, despite its somewhat deeper space, also arranges most of its male protagonists parallel to the picture plane, and Loplop Presents the Members of the Surrealist Group [Fig. 8], in which the silhouette of Ernst’s avian alter ego presides over a framed mass of photos of various surrealist males. Ernst also plays variations on this presentation theme. Take, for example, Rendevous of Friends—the Friends Become Flowers [Fig. 9], with its mass of abstracted vegetable matter, again flat against the picture plane. In typical Ernstian fashion identity is suggested by the title; but here there is also a clue as to the kind of transformative game that the artist favors. If the surrealist group can be repainted as flowers, then why ‘present’ them as a Desnos-inspired horde?

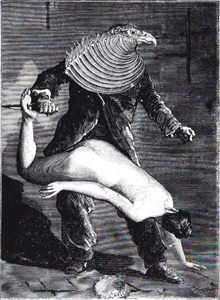

As Ernst’s series developed, this original surrealist identity with its heroic overtones became submerged, and it has remained submerged vis-à-vis art history, which has viewed the paintings only in light of their basic fascist identity, not in terms of this repressed surrealist one, which is repressed in the best and most obvious Freudian sense and therefore requires release, possibly in the surrealist friendly arena of wit or dreams.[11] Consider that the The Angel of Hearth and Home [Fig. 6] was retitled by Ernst in 1938 as The Triumph of Surrealism, “a despairing reference to the fact that the surrealists with their Communist ideas had been unable to do anything to resist fascism.”[12] Ernst’s ironic title functions according to Freud’s Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious, which reminds us that a “favorite definition of joking has long been the ability to find similarity between dissimilar things—that is, hidden similarities.”[13] Here the joke reconnects the fascist and surrealist identities in the barbarian series, and the winged beast reveals itself as both the ironic and literal triumph of surrealism—the triumph of the barbarians, one way or another. Ernst’s grattage technique—a form of rubbing and scraping of and against the still-wet paint used in The Barbarians—discloses this double identity not only as image but also as object, as the painted surface itself. Ernst’s development of grattage represents an attempt to align his painting practice with the purely surrealist one of automatic writing. The surrealist movement, defined initially as pure psychic automatism, was always conflicted about the possibility of properly surrealist painting. In the third issue of La Révolution surréaliste (the same issue that featured “Description d’une Revolt Prochaine”) Pierre Naville had, for example, asserted that “there is no such thing as surrealist painting.”[14] Painting (with the early exception of Masson’s automatic drawings) was deemed too meditated to honestly and accurately access the unconscious. The grattage technique, because less controlled and more spontaneous, was closer to Breton’s definition of surrealism than the slower process of hand-painted dream photography. And in The Barbarians grattage is employed exclusively in and on the bodies of the painted creatures. They are made out of grattage, which, like frottage and the later decalcomania, is the closest Ernst ever got, in terms of technique, to pure psychic automatism and thus orthodox Bretonian surrealism. The figures’ bodies define surrealism at the level of technique, which is here automatic. But hypnotic techniques, which the surrealists equated with potential liberation, have also been investigated in an attempt to comprehend fascism, to make sense of the subordination of a mass to the individual will, something which according to theory should have been antithetical to fully individualized bourgeois identities.[15] Automatism—and thus Ernst’s grattage—implies a passivity in relationship to a superior ego force and thus the archaic or fascistic dark side of the surrealist project of liberation. It can be implicated in fascism as convincingly as celebrated for surrealism. Could Ernst have been criticizing, perhaps unconsciously, the way the members of the surrealist group were behaving by the late thirties? This is, after all, the moment not only of the looming threat of Hitler and the Spanish Civil War, but of Ernst’s chafing under the authority of Breton—a surrealist authoritarianism that would lead to Ernst’s eventual break with the group. Can we begin to differentiate the picture’s individual barbarians, to define their relationships to each other? The bird-hybrid on the painting’s left, with her ballooning skirt shape and more delicate gesture and proportions, reads as female when compared to the hulking barbarian to her right. Rewald suggests a possible family unit: “The dark female leads the way as her male companion turns to look at the strange animal—perhaps their offspring—clinging to his left arm.”[16] This interpretation gains credence in light of Ernst’s many fantasy statements and the particular interactions of his iconographic systems, which tend to create complex constellations rather than stable groups of meaning.[17] Bird imagery is an overarching theme in Ernst’s work and has a particularly labyrinthine iconography [figs. 10 and 11]. Ernst, according to his well-known autobiographical writings, cultivated a purposeful confusion between birds and humans, derived for him from the fact that his loved and trusted pet bird died on the day one of his sisters was born.[18] Birds are thus associated with death, which reinforces the fascist identity, but also typically with flight and thus freedom, a quintessentially surrealist value, and also with Ernst himself, who was said to look like a bird and was often described as such, both because of his facial features and as a laudatory metaphor for his personality.[19] Birds have sexual meaning in Freudian mythology and particularly in German as a slang reference to intercourse.[20] Ernst also invented Loplop as his bird alter ego, allowing us to read the bird-child as a coded oedipal self-portrait.[21]

Bird-mother on the left, father to her right, and bird-child as Max Ernst constitute a classical oedipal triangle. The father’s right arm with its pointed, phallic fingers lunges at the mother’s genital area. This is a gesture of sexual union.[22] His arm also covers the mother’s genitals and therefore blocks her sexual availability, as per oedipal prescription. Consider that the bird-child is facing and possibly moving (thrusting its neck) to the left, towards the sexual enticements of the mother, as is the father with his aggressive striding and simultaneously penetrating and covering gesture. Father and son compete here for access to the primal mother. This sexual combat, moving always left, is reinforced by the enigmatic figure in the distance, also facing left, holding or pushing an ambiguous object that can be read as phallic, pointing towards the mother-creature. This sexual geography combines with the literal westward mapping of the fascist reading to suggest a conflation of national and sexual destiny—a conquering fascist male; passive, yielding Paris to the left/west. This oedipal field is, like the twinned fascist-surrealist identity, inscribed even at the level of technique. Grattage is one of Ernst’s many attempts to avoid orthodox, academic image-making like that of his father, a technically proficient but unimaginative amateur painter with a conventional style. In recalling his artistic beginnings Ernst admits to the overt, if not to say extravagant, oedipal nature of his artistic process:

Then the symbolic violence begins: the father brandishes a fat crayon, sending horrible painted animals into a whirling vase, the crayon becomes a whip, the vase becomes a top which advances menacingly towards the Ernst-child’s bed. The primary psychosexual weapon in this essay of Ernst’s is painting itself, a too-obvious metaphor for sexual power, represented by the whip, literally born out of the father’s spent crayon. The title of this essay, “Beyond Painting,” represents not only technical possibility but the artist’s utterly Freudian aspiration to move beyond painting and thus beyond the castrating power of the father, who is always present, artistically, as tradition, as anything not invented or re-invented by Ernst as Oedipus. It is not surprising that Ernst equated painting with sorcery and hermetic lore. He wrote: “Max Ernst Died the 1st of August 1914. He resuscitated the 11th of November 1918 as a young man aspiring to become a magician and to find the myth of his time….” His peers liked to play along: Breton, for example, compared Ernst to legendary medieval alchemist Raymond Lull in his 1928 manifesto Surrealism and Painting, and nearly ten years later Dorothea Tanning painted her husband wearing a sorcerer’s vest, holding fire in one hand and conjuring a spirit bird.[24] Ernst favored alchemical imagery and mythology throughout his career; grattage is an alchemical technique in that it transforms base or overlooked material into artistic gold. The Barbarians belongs to Ernst’s occultism as much as it does to his Freudianism.[25] Its human-animal hybrids and subordination of specific time, scale, and place to the demands of myth evoke the 17th century alchemical engravings of Johann Daniel Mylius and Michael Maier, with which Ernst was probably familiar [Fig. 12].[26] In fact, the painting functions as a chemical wedding, an alchemical theme to which the artist returned throughout his career.[27] Such a union of male and female operates alchemically as part of a system of binaries—sun and moon, mercury and sulfur, life and death—whose unity or offspring is always the coveted Philosopher’s Stone, emblem of spiritual perfection. Chemical weddings, like two-headed hermaphrodites, are images of reconciliation in the hermetic imagination, often the last stage before perfection. We have already seen that the father’s arm marks a clear, though ungentle, union with the mother; their offspring, the spiritually perfected Philosopher’s Stone, is the bird-child, doubly identified as Ernst himself because of its position in the oedipal triangle and its possible identity as Loplop. Ernst, fond of trying on different identities in his work, also liked to wear the perfected mask, which reinforces the surrealist self-identification even as the implications of violence reiterates the fascist one.[28]

Alchemy also helps to identify the diminutive background figure, which can be read as an alchemist and its sprouting phallic shape as a bellows, used to stoke the alchemical fires. The figure’s stretched arms correspond to those of an alchemist engaged in such work. The bellows are a common enough alchemical image and can be found in Bruegel’s The Alchemist, for example [Fig. 13; detail and related engraving, Fig. 14]. The trio of creatures up front is produced by the labors of the background figure and therefore we find, by way of the alchemist on the horizon, a picture of this picture’s own making. The alchemist figure could well be another stand-in for the artist: alchemist equals creator, creator here means painter, and the painter is naturally Max Ernst. He thus portrays himself as the alchemist on a spiritual quest and as the coveted Philosopher’s Stone—the magician in search of a myth and the perfection of the myth itself. Note the sexual indeterminacy of this alchemist figure: phallic but dressed probably as a woman. Like his conjured barbarians, like the painting itself, this painter-alchemist Ernst has a doubled identity, such that the linearity of the hermetic fable is complicated by the play of self-portraits in various—often doubled—states of questing and perfection. Such multiplicity is indicative of what we have in The Barbarians: an effect rather than a prescription, the look—and not necessarily anything more than the look—of secret wisdom. Alchemy does not trump Freudianism here nor does it dissolve the overt vision of fascism. What the occult does do is combine fascist and surrealist identities in light of a philosophy that insists on such a union as spiritual and positions the painted object as the site of this paradoxical union. Such conjunction is not without historical resonance, as the occult was inspirational to both fascism and surrealism as they advanced towards obscurantism and revelation, and could suggest an artist’s attitude towards catastrophe, in which catastrophe is part of a larger spiritual whole, and believes therefore in the purity or theology of art. For Ernst and others like him, on the eve of disaster, art-for-art’s sake might have been the only remaining hope.

Endnotes 1. Sabine Rewald, Twentieth Century Modern Masters: The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection (New York: H.N. Abrams, 1989), 199. See also John Russell, Max Ernst: Life and Work (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1967), 118-120. 2. Werner Spies, ed., Max Ernst: A Retrospective, (Munich: Prestel-Verlag, 1991), 230, and Waldman, 51. 3. Such conflation of map-geography with painted space is reasonable in Ernst’s case. One of the major paintings of the thirties, Europe After the Rain, is an actual map and suggests that Ernst was comfortable with painting-as-window and painting-as-diagram. 4. Uwe Schneede, Max Ernst (New York: Praeger, 1973), 154. 5. M.E. Warlick, Max Ernst and Alchemy: A Magician in Search of a Myth, with a foreword by Franklin Rosemont (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001), 63-4, and Maurice Nadeau, The History of Surrealism, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Macmillan, 1965), 79-84. 6. “Mob, recognize your master! You thought that you could flee it, flee that Orient that drove you away by vesting you with the right to destroy what you could not preserve, and now that you have traveled around the world, you find it snapping at your heels again. I beg you, do not imitate a dog trying to catch its tail…” Robert Desnos, “Description d’une révolt prochaine,” in La Révolution surréaliste, no. 3, April 1925, p. 25, cited in Michel Foucault, “Society Must Be Defended”: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975-1976, translated David Macey (New York: Picador, 2003), 198-199, and Russell, 97. 7. André Breton, Manifestoes of Surrealism, trans. Richard Seaver and Helen R. Lane (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1969), 29. 8. Warlick, 39. 9. This serial aspect of Ernst is understudied, according to Diane Waldman. See Max Ernst: A Retrospective, exh. Cat. (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1975), 51. 10. Compare to the similarly executed—though more Mediterranean—Two Girls and a Monkey Armed with Rods of the same year, with its obviously demarcated sexual difference, particularly in the treatment of the girls’ breasts. 11. See Hal Foster, Compulsive Beauty (Cambridge and London: The MIT Press, 1993) for a discussion of Ernst in terms of the Freudian primal scene. 12. Schneede, 154. 13. Sigmund Freud, Jokes and their Relation to the Unconscious, trans. and ed. James Strachey, introduction by Peter Gay (reprint, New York: Norton, 1989), 7. 14. See David Lomas, The Haunted Self: Surrealism, Psychoanalysis, Subjectivity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 9. 15. See Theodor W. Adorno, “Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propoganda,” in The Culture Industry: Selected Essays on Mass Culture, ed. J.M. Bernstein (London: Routledge, 1991). 16. Rewald, 200. 17. See David Hopkins, Marcel Duchamp and Max Ernst: The Bride Shared (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998), 95-180, for the substantial range of references and overlapping iconography in Vox Angelica and The Robing of the Bride. For a similarly thorough discussion of psychoanalytic references in Ernst’s work, see Elizabeth M. Legge, Max Ernst: The Psychoanalytic Sources (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1989). 18. Bird imagery and the relationship between whole, naturalistic birds and imaginary bird-human hybrids form overarching themes in Ernst’s work. Violence is usually being done by the bird-hybrid, not to him/it/her. See especially the collage novels. ‘Normal’ birds have a less lopsided relationship to destructive identity. 19. Stokes, 228. 20. Ibid, 234. 21. According to Ernst himself: “The 2nd of April 1891 at 9:45 AM Max Ernst had his first contact with the sensible world, when he came out of the egg which his mother had laid in an eagle’s nest and which the bird had brooded for seven years.” From “Some Data on the Youth of M.E., As Told by Himself,” View 2, no. 1, special Ernst issue (April1942): 28-30. 22. Ernst was fond of such coded penetrative gestures—see, for example, The Robing of the Bride, which shares many of the sexual and hermetic themes in the barbarians. 23. Max Ernst, Beyond Painting and Other Writings by the Artist and His Friends, Documents of Modern Art Series, edited by Robert Motherwell (New York: Wittenborn, Schultz, 1948), 3. 24. Ibid, 94. 25. Warlick offers a thorough discussion of such influences. 26. For a compendium of such engravings, see Stanislas Klossowski de Rossa, The Golden Game: Alchemical Engravings of the Seventeenth Century (London: Thames & Hudson, 1988). 27. See Robing of the Bride (1940) or Chemical Nuptials (1948). 28. For an analogous heroic example, see Plate 58 of La Femme 100 têtes, le superior des oiseaux, effarouche les derniers vestiges de la dévotion en commun [Fig. 10]. Loplop is portrayed here as a ‘normal’ (albeit enormous) bird swooping towards a crowd from the top of a flight of steps.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

© 2004 PART and Emily Bills. All Rights Reserved.