| |

In this brief essay I will attempt to address

the issue of perspective in two church doors that are separated

by half a millennium. The first is Lorenzo Ghiberti's Gates of

Paradise of the baptistery of the Florence Cathedral, completed

in 1452. The second is Giacomo Manzù's Gates of Death

of St. Peter's in the Vatican, completed in 1963. The gerund "piercing"

within the above title is borrowed from Hubert Damisch's The

Origin of Perspective, in which the author links to a certain

extent the 1490-96 painting of Vittore Carpaccio entitled Recepetion

of Ambassadors to frescoes in Assisi. Referring to the Reception

of the Ambassadors, Damisch reflects: "In this respect it recalls

Giotto's [sic] frescoes in Assisi: the painting 'pierces'

the wall all the more effectively because it concedes its presence,

incorporating mural elements into its own field."1

|

|

|

From such a point of departure, we seem to

witness earlier means of representing three-dimensional and architectural

space pictorially. The frescoes of Assisi recall an earlier use

of perspective, which is evident in other works by Giotto di Bondone2.

The illusion of depth arrives at various standardized and theoretically

established, graphic and pictorial means about a century later.

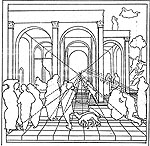

A number of panels of The Gates of Paradise (Figure 1) depict

three-dimensional space through linear perspective. Yet toward the

middle of the twentieth century we come across significant departures

from these rules within the formal design and implementation of

The Gates of Death.

The substantive phrase "'piercing' the

flat" can itself be read as being charged with intonations.

It is somewhat complex to reduce the status of the flat to finite

conclusions within the domain of the two Gates, as they are both

somewhat imperfectly cast in bronze. The high and low reliefs of

both doors echo to a certain extent the visible perforations of

their alloys. Such perforations are at times minor and at times

major. They can be regarded as intentional or accidental marks on

the surfaces of the cast figures and grounds of both Gates. Yet

there remain somewhat definitive differences through which the two

doors in question present images. While the panels of The Gates

of Death do not depart from the figure per se, they seem to

bear no evidence of orthogonal projections in the service of illusionistic

depth. At the same time, however, The Gates of Death remain

figurative, despite the development of twentieth century abstraction.

Among other methods and solutions regarding

representation through bronze reliefs, The Gates of Paradise

contain orthogonally systematized means of producing the illusion

of architecturally framed three-dimensional space. More specifically,

the gates have used "Brunelleschi perspective", albeit

not fully systematized and not in each panel. Conversely, The

Gates of Death rely on the figure and its ground as the means

of representation. The flat surfaces of the panels here are articulated

through literal piercings, scratches, gashes, and instances of the

unmistakable dissolution of the body parts of the figures. The final

product seems to lack "order," "theory," "rule,"

or visual "depth" through perspective. In fact, one could

read the distortion of the figurative as the sign of a departure

from iconic signifieds through the distortion of iconic signifiers.

Here, what seems to be equally at play as figure versus ground are

seemingly random and deviant marks left on metallic surfaces. A

notion which one might be led to associate with The Gates of

Death is partial visual chaos, should one be tempted to link

its binary opposite, order, as a characteristic of the Renaissance,

which adheres to the return to certain intellectual paradigms of

ancient Greece. More specifically, it is the Euclidean theorem of

mathematically calculated proportion that we find revived, theorized

and expanded from the two-dimensional givens of linear geometry

to a "visual pyramid" as a means of representing three-dimensional

space pictorially. 3

This is not to say that the Renaissance can

be reduced to the single judgment of "order," as a work

of art itself defies verbal reduction. In fact, image versus text,

despite their inseparability on the level of perception, can be

said to remain distinct entities. As much as image and text are

interwoven within the realm of icons, they are physically separate

entities. Image and text remain detached within the domain of the

mind, while they are inseparable therein. I borrow two terms from

a methodology that Damisch proposes in addressing the link between

language (the primary means of art history) and perspective. My

analysis of a few features of the two gates is intended to be "demonstrative"

rather than "declarative." Addressing the "polysemic"

nature of the image and its problematics in relation to language,

Damisch observes that the gerund painting-and likewise piercing

I would add-is a progressive form of the verb. Such a form, the

author claims, indicates "the essentially performative nature

of a practice that has no existence, in contradiction to language,

save in the act, the exercise."4

The term "polysemic" is the adjectival counterpart of

the noun "polysemy," which signifies "many meanings."

From such a point of view the gates in question continue to bewilder

the spectator, as they both contain adherences to and digressions

from certain established domains of their cultural contexts. Their

juxtaposition furthermore multiplies the possible set of formal

and cultural meanings.

It is particularly architecture, with its

calculated geometric conditions and the projected coordinate system,

which plays a central role in the two-dimensional representation

of three-dimensional space in a number of Ghiberti's reliefs. This

is not to say that the notion of perspective is obliterated in those

panels where architecture is not a predominant tool for attaining

illusionistic space. Consider, for example, the uppermost left panel

Genesis of the Gates of Paradise. Here, it is primarily

through the diminishing scale of figures arranged in a somewhat

triangular order with a base positioned on the lower edge of the

square that the illusion of depth is signified. Likewise, it is

the varying magnitude of the trees, somewhat diminished in receding

"space," that evokes three-dimensionality. The very medium

of high relief here is a means of not merely signifying the third

dimension within the no-longer-flat space, but materially raising

above the vertical flatness of the doors. Hence we have at least

a double means of constructed space here: one through the somewhat

gradual but not necessarily consistent shift of the scale of figures,

and another through the very nature of the reliefs. These reliefs

entail the additions and subtractions of form on the panel, which

continue to shift between the domains of the tactile and optical.

The three-dimensional high and low reliefs have put into use two-dimensional

means of representing "depth." Furthermore, the draperies

of the figures are prominent representations of the culturally manufactured

versus the natural, such as the human body or the pine trees. Yet

these elements, whether they are representations of the cultural

or the natural, remain somewhat apart from the technique of architectural

perspective. An instance of the physical as well as illusionistic

emergence from the two-dimensional space of the relief through applied

linear geometry takes place in the execution of a fragment of architecture.

Relative to the horizontal, the approximately

30-degree angular inclination of the top of the arch in the Genesis

designates an oblique façade. What we have is a partial quadrilateral.

The somewhat vertical yet non-parallel sides of this quadrilateral

approach each other as if to form an inverted V with an absent apex.

This trapezoid is one instance of linear perspective, which denotes

the beholder's position. The beholder is assumed to be at an angle

relative to the façade, at a distance from it, and at a lowered

position. However, the remainder of the scenery denotes a spectator

viewing it from an upper level relative to the figures in the foreground.

Therefore the linear and geometric attributes of the arch here emulate

one form of perspectival space. Such an orthogonal representation

of the arch is coupled with the more-or-less scalar establishment

of "depth" or "three-dimensionality" through

the figures. Furthermore, this fragment of architecture "drawn"

through a method of perspective, while physically "piercing"

the flat surface of the alloy as a relief, is itself illusionisticly

and sculpturally punctured. The arch is itself "infiltrated"

through a flying heavenly body (is it an angel or God?), whose central

axis intersects the concentric circles surrounding the Creator.

Shall we incline to the possibility of reading this entry of the

Creator into a moment of perspective as a latent signifier of the

"creation" of perspective as such?

I would like to set forth one methodological

statement as a relevant answer to the preceding question. Laurie

Schneider Adams opens up her discussion of Brueghel's Icarus

by stating:

Because myths contain psychological

truth, they offer rich material for the visual artist. James Saslow

has shown that different artists, as well as different cultures,

respond to a myth according to individual and social forces. The

mythic "text" is a "context," which the artist

invests with his own inclinations and talent rather than producing

an objective, or literal, illustration of it.5

From such a point of view, then, the signifiers

of Genesis render the representation through linear perspective

as a means of examining questions that suspend the semantic closure

of the icons in question. They render the status of these icons

multi-faceted or polysemic. They invite social questions rather

than remaining solely on a formal level.

Moreover, whether the viewer would attempt

to link the panels of either The Gates of Paradise or The

Gates of Death to available biographic details of their artists

or, alternatively, to a set of broader cultural questions, the panels

activate such polemical parameters as icon versus form; image and

substance; the interrelations of the verbal and the visual; class,

art and politics; psychoanalysis; epistemology. These are discursive

parameters that resist disciplinary partitions and call forth interdisciplinary

approaches. In short, these parameters call forth such "social

forces" as those to which James Saslow refers in the preceding

citation.

Compared to the Isaac (middle left

panel of Gates of Paradise), Genesis utilizes a rare

instance of the presentation of depth through casamenti, an architectural

setting, and the linear perspective attached to it. The Genesis

relies on a 45 mm projection at the bottom of the panel and a 35

mm recession at the top. Such is the nature of the stage set in

which the scale of the characters are somewhat proportionally depicted

through their heights. The figures are composed in various sequences,

which presume the illusion of space. The Isaac, on the other

hand, depicts a fully worked out linear perspectival model. This

panel utilizes architecture as a vital tool for a geometrically

calculated presentation of depth through methods of linear perspective.

Such a two-dimensional illusion of depth through architecture calls

forth various linear geometric methods "invented" by Filippo

Brunelleschi and later formulated by Leone Battista Alberti.

Richard Krautheimer6

describes the method through which an instance of Renaissance perspective

has been put to use in The Gates of Paradise. Referring to

the Isaac, which he contrasts with the Cain and Abel

regarding its use of perspective, Krautheimer states that "Ghiberti's

art and workmanship reached a climax [of perspectival technique]."7

As it is evident through a glance, the "complex and infinitely

subtle composition is strengthened and indeed, made possible by

the architectural setting which fills almost the entire height of

the relief. A monumental hall with wide arches and tall pilasters

underscores the successive events of the story, setting off the

single scenes in separate spatial units and calling attention to

the protagonists." 8 Krautheimer

emphasizes three functions regarding the role of architecture and

its use in the panel. First "it supports and clarifies the

composition and narrative;" second, "since it follows

a linear perspective, it contributes to the sense of a continuous

all-embracing space;" and third, "it enables the spectator

to measure distances, evaluate the relative size of figures and

objects and clearly comprehend movements and relationships."9

In short, it is the use of architectural and to a certain extent

geometrically calculated perspective to interweave narrative, depth

and proportion that are evident in the Isaac.

|

|

|

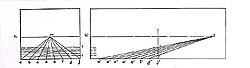

Yet there remain acute differences that set

the pictorial composition of the Isaac apart from either

the practice of Brunelleschi or the theories of Alberti read as

being coherent or definitive. As Krautheimer's diagram of the Isaac

demonstrates, there are a number of deviations from Alberti's fundamental

elements of vanishing point, distance point, horizon, and so forth.

The non-existence of a single or multiple vanishing points as indicated

in Diagram 1 can be read as a non-adherence to a simplified Albertian

model. As this model itself remains somewhat unstable, it has its

own "gives and takes" as the reader moves from one part

of Della pittura to another.10

|

|

|

Krautheimer concludes his analysis of linear

perspective in The Gates of Paradise by noting their relation

to the implementation of perspective through Brunelleschi's methods

and Alberti's Della pittura. He assumes that "it is

unlikely that he [Ghiberti] consciously tried to disregard Alberti's

perspective construction. More likely he simply set out to reduce

what he considered practical essentials." Referring to the

extent to which Ghiberti put Alberti's perspectival theory into

actual use, Krautheimer concludes his analysis of Ghiberti: "After

all, his mind had never run along theoretical lines, and almost

unaware he slipped out of Alberti's perspective system as suddenly

as he had slipped into it."11

That slipping out of an established system

on the part of Ghiberti, whether intentional or not, conscious or

unconscious, can be read to activate a polemic within the domain

of "the myth of Icarus" mentioned above. Such an approach

calls forth the transformation of "text" into "context."

Here, the objective and its illustration become for the producer

and the spectator means of undoing the fixed. Setting aside Ghiberti's

own psychological

|

|

|

parameters, one could pose the following query:

Read from a broader standpoint, does the presence of multiple and

non-singular vanishing points in Ghiberti's Isaac induce, to

a certain extent, parallels to Brunelleschi's own departure from purely

geometric, perspectival and hence ideally-stable formation of two-dimensional

illusion of space? After all, it has been conjectured that Brunelleschi's

formation of a stable illusion was activated through the insertion

of the reflection of the sky on an area on the painting covered in

silver leaf. The stabilized and idealized eye point and vanishing

point through Brunelleschi's use of an apparatus were intended to

provide the mirror reflection of an image so that the single "eye

point" and the vanishing point were geometrically definable and

precise. Yet the foreclosure of the device was transgressed through

the instability of double reflections: a reflection of the still,

painted picture which was to be destabilized through the "mirror"

of a silver leaf echoing actual clouds of the sky. Damisch addresses

the function of Brunelleschi's silver leaf by linking it to Lacan's

"Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I" by

interrogating:

But why the mirror? As opposed to

the unweaned child who acknowledges the mirror image as his own,

and who anticipates, through this form, the Gestalt or bodily integration

and coordination it still lacks, the painter's image is not transformed

by the specular reflection. With regard to unity, the kind of perspectival

coherence characteristic of Brunelleschi's panel, which made it

novel, had nothing imaginary about it, being the fruit of precise

calculations and carefully considered decision: given a construction

organized around a single point of view, the flat mirror did nothing

but reverse its lateral orientation. But this reversal is not without

its problems. For it would seem to provide support for the hypothesis

that Brunelleschi executed his painting with the aid of a mirror,

directly on a reflective surface, in which case he could have needed

to use a second mirror to reestablish conformity with the order

of things, as this image, having been constructed directly on a

mirror reflection, would have effected an exchange of left for right

and right for left. 12

Thus if the lineamenti (the schematic

outlines), the misure (the means of representing reality),

the ragioni (the proportionate relationships), and the casamenti

and piani (the architectural settings) in the reliefs of

The Gates of Paradise disobey the "scientific"

rules of a physically fixed "gaze," it is because the

semblance of reality could not be totally reduced to a purely Euclidean

geometry; it is because pure geometry remains insufficient as a

means of accounting for the image traced on the retina which resides

within a pulsing body.

|

|

|

About four- to five-hundred years later perspective

had come to either explicitly reverse itself or simply depart from

the pictorial field in the West. As if a means of resisting illusion,

the disintegration of three-dimensional space would become a companion

of the partially dismembered figure in much of visual representation.

Hence the figure would at times dissolve with the ground, as if

to resist depth in order to turn its vantage point to the essential

conditions of its own representation. The Gates of Death

explicitly counteract depth through their own means, without a total

departure from figures under the guise of icons. In fact, the unity

of the figures would be undone through the submission of the index

on them as such; these indexes are marks which were mere

traces first incised on clay in order to be cast in bronze. The

index is a semiotic term that has by now entered the discursive

arena of art. It is as if the partial or total dissolution of the

figure in the visual arts has necessitated an expansion of interpretive

terms. Through the semiotic domain the term index has been marked

as a category of signs apart from symbols and icons. As a large

portion of twentieth-century art has eliminated definitive icons

and symbols, setting forth material and form as content in many

instances, the term index has been attached to the very physicality

of marks and shapes within a given medium. Therefore, while the

icon and the medium forming it were sides of the same coin during

previous centuries, much Western art of the twentieth century, whether

figurative or abstract, departs from the icon as such. It resists

the closure of finite meanings. "Since things are as they are

("it is as it is, it is as it is," a formula dear to Kafka,

marker of a state of facts), he will abandon sense, render it no

more than implicit; he will retain only the skeleton of sense, or

a paper cutout."13

Why, one may ask, does Death on Earth

(lowermost right panel of Gates of Death) retain the presence

of the figure, including a chair, draperies, the profile of a head

and a crying child? Why does it undo the figure, extending certain

physically negative and positive outlines of the figures, such as

the curves emerging from the child's left hand? Or what is the visual

function of an independent curve on the ground above the chest of

the woman? Along with these floating lines there are also metallic

"points" which are indexes of somewhat random and arbitrary

frottages on clay during the initiation and casting of the relief.

A direct departure from and the questioning of perspective remain

marks of alternative directions of thought in the West. The dissolution

of the figure and its ground as means of attaining the abstract

can be read as partially linked to the individual of the machine

age. Such an individual was also at the threshold of World War I.

The abstractions of Mondrian or Malevich early in the century can

be read as either partially detached from the social field or as

signs of the infrastructures of certain ideologies-or both. The

concepts linked to such works range from the total autonomy and

self-justification of abstraction to its status as a symptom of

prewar social conditions. Such conditions of labor have been identified

under the rubric of technorationalism. These abstractions would

be followed by partial returns to the figure in the works of Le

Corbusier or Léger for example, whose organicism indicates a politically

disturbing social field that had been traumatized by two World Wars.14

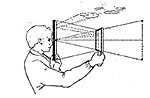

And the seemingly abstract output of a closer contemporary of Manzù,

such as Lucio Fontana (Figure 3), seems to aim at a means of undoing

the optical autonomy attached to the silence of the monochrome.

If it undoes the silence and autonomy of the monochrome, it is through

a "violent act" performed on the very canvas in order

to render its material underbelly unmistakably "tangible"

through sight. Yet unlike the abstract or "formless" means

of representation which had come to characterize its century as

a central visual direction, The Gates of Death of Manzù

maintain the figure, only to negate it from within, through intentional

incisions and accidental pores. Hence the accident here becomes

a reciprocal parameter of the intentional.

To maintain, and yet to de-construct

form, to represent death in space yet to undo the void of space

through formless lumps and linear cavities which seem to echo rope

parts, drapery, as well as nothingness-linear cavities as such:

how are we to read these variants situated in an eloquent High Renaissance

edifice, near a pair of Filarete doors? What is the abandonment

of perspective here a sign of, given the availability of Alberti's

Della pittura, Filarete's Treatise on Architecture

and Brunelleschi's lessons as possible means of representing three-dimensional

space through well-formulated architectural theories? What questions

does Death in Space raise regarding the status of the twentieth-century

artist who has departed from Alberti's or Filarete's techniques

of visual representation of three-dimensional space?

"Once, religion had a power and a reality

touching Dante and Michelangelo and others. At that time, dogmas,

rites, symbols and images had real meaning for man and so, as a

result, [they] did religious art which figured them. But today the

images no longer speak the same way because life is elsewhere in

science and the industrial revolution which has changed the world."

15 These were the sculptor's thoughts

conveyed to Pope John XXIII during the time when the doors were

being put forth in clay in Rome then being sent to Milan to be cast

in bronze.

However, it would be misleading to reduce

the Renaissance to mere dogma, rites and symbols in the visual filed,

as put forth by Manzù above. Yet the romantic conception of

selfhood hoped for in the past seems to have departed from the individual

of the twentieth century. Or perhaps characterizing the past with

a romantic conception of selfhood or the validity of religion had

led many twentieth-century artists to depart from tradition to its

fullest extent. If there was such a thing as "individual creative

will," it was to reflect the very parameters of industrial

labor that had entered the venue of art through such notions as

seriality, repetition and depersonalization. Such an approach targets

the end of material perfection within one of its most prohibited

contexts in the Western world in this case-the façade of

St. Peter's. From a semiotic standpoint, it would be the index that

would function as a shifter, a destabilizing type of a sign that

would abandon the space of perspective in order to render the icon

itself polysemic. Here, the tactile conditions of the material would

function as a rearticulated sign of what Diderot was to equip the

blind man with in his "Letter of the Blind: For the Use of

Those Who See." The fictive blind man would state: "it

is touch that alerts us to the presence of certain modifications

that remain imperceptible to the eyes until they have been informed

of them by our sense of touch."16

And by linking the perspectival ideal to the sense of touch Lacan

would render the categories of the two senses interdependent and

de-stable. Instances of Lacan's discourse seem to be not unlike

the words of Diderot's fictive blind man who said: "Yet we

shall all pass one day, and without any possibility of measuring

either the real space that we once occupied or the exact time that

we have lived. Time, space, and matter are perhaps only a point."17

The Gates of Death, by destabilizing form through haptic

disjunctions, open themselves up to the alienation of modern man:

lonely, no longer with Christ and Madonna, but perhaps with Karl

Marx.18 But even the role of Marx had

come to signify the partial role of money in the self, no longer

the only factor of alienation. Economics is a parameter that Lacan

would add to the matrix of the unconscious conditioned by the visual

and tactile. As if following the path of Diderot's blind man, Lacan

would render time, space and matter as "points." He would

do so through his use of an unsettled mode of speech and writing.

The haziness of such a notion of "points" in certain ways

parallels the alienation of the subject. Lacan presented his seminar

on alienation on May 27, 1964, a month before the unveiling of The

Gates of Death by Pope Paul VI-June 28, 1964.19

The slashes of the monochrome canvas of Lucio

Fontana's Concetto Spaziale-Attese of 1963 pierce the totally

abstracted high modernist myth of the purity of the monochrome.

These cuts expunge the very coherence and stability of form at its

most abstract. Here, the very tool of the index functions as a signifier

whose signifieds would remain without a final interpretant. In The

Gates of Death we witness slashes, cuts and bruises targeted

toward the figure as well as toward the flat space surrounding and

at times dissolving with parts of the figure. Its level of signification

is thus rendered parallel to a numeric order that Lacan borrows

from Descartes in order to illustrate the convolution of alienation:

20

1 + (1 + (1 + (1 + ( . . . )))).

Yet while Fontana's index violates the "purity" and autonomy

of the monochrome flat within an unreligious context, Manzù's

indexical marks were intentional violations of the "purity"

of the flat, the icon and the figure within their most prohibited

place-in the glory-laden shrine of the Eternal City. His mutilation

of the figure renders the status of the Other a companion of the Self.

The status quo of such a Self would remain incalculable, like the

above cardinal order that Lacan selects. The Self and the Other would

here become interchangeable companions of the Figurative and the Abstract.

In 1966 in Galleria La Salita in Rome, Richard

Serra exhibited Live Animal Habitat. These were cages filled

with live and stuffed animals. Such an approach was a means of departing

from the two-dimensional and entering the realm of the real as such.

Yet this was a realm with no finite beginning and end, but one of

mere production as self-critique.21 This

was another means of unveiling the disunity of the Self. The cultural

implications of the physical piercing of the flat in order to give

way to the formless upon The Gates of Death are various.

One means of departing from the objective production of icons for

Manzù was to state the status of the modern subject-uncertain

of a whole self as such, having left behind the role of religion

and that of theoretically established perspectival representation.

Once past the territory of the religious or

the figurative icon, Death in Space, Death on Earth,

Death of Abel, Death by Violence and the other panels

could become replaced by new titles: Drawing the Line, Forging

the Polis; Deterritorialization and the Withdrawal of the Line;

Mass Society and the Collapse of Designo; The Line as Psychic

Horizon; Lines without Subjects; Line as Pure Event; Field, Boundary,

Consciousness. These were the titles of a lecture series entitled

Lines of Sight: The Status of the Line in Modern Visual Representation

that Norman Bryson held at Cooper Union in 1999. Contextually somewhat

distant from The Gates of Death, these titles are nonetheless

companions of The Gates of Death on a broader cultural level.

The status of the line in much of modern visual representation is

a departure from a systematic space marked by a horizon and a vanishing

point. It is a means of "piercing" the flat not through

illusion but through actual marks like those of the graffito artist,

or through cuts such as Fontana's "signature." Line thus

becomes a pure event, not only to undo the illusion of perspectival

depth, but also to obliterate the notion of absolute purity and

absolute flatness once attached to High Modernism. Such a means

of representation can be read as an attempt to obliterate the notion

of the unity of the Self as well.

And yet. The Gates of Death and The

Gates of Paradise, despite their utter differences, both digress

from systematization. If The Gates of Death are nonconforming

to certain paradigms of their sanctified or temporal settings, it

is because they adhere to neither the figure as a whole nor the

abstract as such. They depart acutely from Albertian or aberrant

depth as well. The panels of these doors have left the unity of

the outlines and inner shapes of their figures vastly incomplete,

as if to mirror the adamant resistance of the body to utter stability

of any form-whether the corpus is alive, is taking its leave

of life, or has become an inert corpse. The partial figure here

thus becomes an "icon" of the corporeal self which continues

to trade matter with its surrounding, whether this matter is air,

food, light, or the causal agent of some other afferent or efferent

activity. Such is the realm of Lacan's indeterminate object a.

And The Gates of Paradise, despite their partial adoption

of the costruzione legittima, deviate from the Albertian

idealism of a geometrically determined single vanishing point in

their own ways. To begin with, Brunelleschi's single-eye and stationary

adherence to perspective was itself mediated through the instability

of the sky obtained through the reflection on the silver leaf painted

on his Baptistry panel in Florence. Here the motility of the image

of the clouds becomes a conjugate to the dazzling, pulsatile blink

of the eye. This blink remains inimical to purely systematized and

stable norms of visuality. Alberti himself shifts in book II of

Della pittura to warn the reader of the risks of the perspective

paradigm. These risks are to a certain extent flattened in Ghiberti's

rendition of perspective.

References>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|