Ghiberti and Manzù: Alternative Means

of "Piercing" the Flat

by Raphy Sarkissian

|

In this brief essay I will attempt to address the issue of perspective in two church doors that are separated by half a millennium. The first is Lorenzo Ghiberti's Gates of Paradise of the baptistery of the Florence Cathedral, completed in 1452. The second is Giacomo Manzù's Gates of Death of St. Peter's in the Vatican, completed in 1963. The gerund "piercing" within the above title is borrowed from Hubert Damisch's The Origin of Perspective, in which the author links to a certain extent the 1490-96 painting of Vittore Carpaccio entitled Recepetion of Ambassadors to frescoes in Assisi. Referring to the Reception of the Ambassadors, Damisch reflects: "In this respect it recalls Giotto's [sic] frescoes in Assisi: the painting 'pierces' the wall all the more effectively because it concedes its presence, incorporating mural elements into its own field."1

|

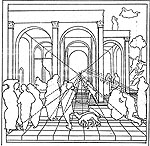

From such a point of departure, we seem to witness earlier means of representing three-dimensional and architectural space pictorially. The frescoes of Assisi recall an earlier use of perspective, which is evident in other works by Giotto di Bondone2. The illusion of depth arrives at various standardized and theoretically established, graphic and pictorial means about a century later. A number of panels of The Gates of Paradise (Figure 1) depict three-dimensional space through linear perspective. Yet toward the middle of the twentieth century we come across significant departures from these rules within the formal design and implementation of The Gates of Death.

The substantive phrase "'piercing' the flat" can itself be read as being charged with intonations. It is somewhat complex to reduce the status of the flat to finite conclusions within the domain of the two Gates, as they are both somewhat imperfectly cast in bronze. The high and low reliefs of both doors echo to a certain extent the visible perforations of their alloys. Such perforations are at times minor and at times major. They can be regarded as intentional or accidental marks on the surfaces of the cast figures and grounds of both Gates. Yet there remain somewhat definitive differences through which the two doors in question present images. While the panels of The Gates of Death do not depart from the figure per se, they seem to bear no evidence of orthogonal projections in the service of illusionistic depth. At the same time, however, The Gates of Death remain figurative, despite the development of twentieth century abstraction.

Among other methods and solutions regarding representation through bronze reliefs, The Gates of Paradise contain orthogonally systematized means of producing the illusion of architecturally framed three-dimensional space. More specifically, the gates have used "Brunelleschi perspective", albeit not fully systematized and not in each panel. Conversely, The Gates of Death rely on the figure and its ground as the means of representation. The flat surfaces of the panels here are articulated through literal piercings, scratches, gashes, and instances of the unmistakable dissolution of the body parts of the figures. The final product seems to lack "order," "theory," "rule," or visual "depth" through perspective. In fact, one could read the distortion of the figurative as the sign of a departure from iconic signifieds through the distortion of iconic signifiers. Here, what seems to be equally at play as figure versus ground are seemingly random and deviant marks left on metallic surfaces. A notion which one might be led to associate with The Gates of Death is partial visual chaos, should one be tempted to link its binary opposite, order, as a characteristic of the Renaissance, which adheres to the return to certain intellectual paradigms of ancient Greece. More specifically, it is the Euclidean theorem of mathematically calculated proportion that we find revived, theorized and expanded from the two-dimensional givens of linear geometry to a "visual pyramid" as a means of representing three-dimensional space pictorially. 3

This is not to say that the Renaissance can be reduced to the single judgment of "order," as a work of art itself defies verbal reduction. In fact, image versus text, despite their inseparability on the level of perception, can be said to remain distinct entities. As much as image and text are interwoven within the realm of icons, they are physically separate entities. Image and text remain detached within the domain of the mind, while they are inseparable therein. I borrow two terms from a methodology that Damisch proposes in addressing the link between language (the primary means of art history) and perspective. My analysis of a few features of the two gates is intended to be "demonstrative" rather than "declarative." Addressing the "polysemic" nature of the image and its problematics in relation to language, Damisch observes that the gerund painting-and likewise piercing I would add-is a progressive form of the verb. Such a form, the author claims, indicates "the essentially performative nature of a practice that has no existence, in contradiction to language, save in the act, the exercise."4 The term "polysemic" is the adjectival counterpart of the noun "polysemy," which signifies "many meanings." From such a point of view the gates in question continue to bewilder the spectator, as they both contain adherences to and digressions from certain established domains of their cultural contexts. Their juxtaposition furthermore multiplies the possible set of formal and cultural meanings.

It is particularly architecture, with its calculated geometric conditions and the projected coordinate system, which plays a central role in the two-dimensional representation of three-dimensional space in a number of Ghiberti's reliefs. This is not to say that the notion of perspective is obliterated in those panels where architecture is not a predominant tool for attaining illusionistic space. Consider, for example, the uppermost left panel Genesis of the Gates of Paradise. Here, it is primarily through the diminishing scale of figures arranged in a somewhat triangular order with a base positioned on the lower edge of the square that the illusion of depth is signified. Likewise, it is the varying magnitude of the trees, somewhat diminished in receding "space," that evokes three-dimensionality. The very medium of high relief here is a means of not merely signifying the third dimension within the no-longer-flat space, but materially raising above the vertical flatness of the doors. Hence we have at least a double means of constructed space here: one through the somewhat gradual but not necessarily consistent shift of the scale of figures, and another through the very nature of the reliefs. These reliefs entail the additions and subtractions of form on the panel, which continue to shift between the domains of the tactile and optical. The three-dimensional high and low reliefs have put into use two-dimensional means of representing "depth." Furthermore, the draperies of the figures are prominent representations of the culturally manufactured versus the natural, such as the human body or the pine trees. Yet these elements, whether they are representations of the cultural or the natural, remain somewhat apart from the technique of architectural perspective. An instance of the physical as well as illusionistic emergence from the two-dimensional space of the relief through applied linear geometry takes place in the execution of a fragment of architecture.

Relative to the horizontal, the approximately 30-degree angular inclination of the top of the arch in the Genesis designates an oblique façade. What we have is a partial quadrilateral. The somewhat vertical yet non-parallel sides of this quadrilateral approach each other as if to form an inverted V with an absent apex. This trapezoid is one instance of linear perspective, which denotes the beholder's position. The beholder is assumed to be at an angle relative to the façade, at a distance from it, and at a lowered position. However, the remainder of the scenery denotes a spectator viewing it from an upper level relative to the figures in the foreground. Therefore the linear and geometric attributes of the arch here emulate one form of perspectival space. Such an orthogonal representation of the arch is coupled with the more-or-less scalar establishment of "depth" or "three-dimensionality" through the figures. Furthermore, this fragment of architecture "drawn" through a method of perspective, while physically "piercing" the flat surface of the alloy as a relief, is itself illusionisticly and sculpturally punctured. The arch is itself "infiltrated" through a flying heavenly body (is it an angel or God?), whose central axis intersects the concentric circles surrounding the Creator. Shall we incline to the possibility of reading this entry of the Creator into a moment of perspective as a latent signifier of the "creation" of perspective as such?

I would like to set forth one methodological statement as a relevant answer to the preceding question. Laurie Schneider Adams opens up her discussion of Brueghel's Icarus by stating:

Because myths contain psychological truth, they offer rich material for the visual artist. James Saslow has shown that different artists, as well as different cultures, respond to a myth according to individual and social forces. The mythic "text" is a "context," which the artist invests with his own inclinations and talent rather than producing an objective, or literal, illustration of it.5

From such a point of view, then, the signifiers of Genesis render the representation through linear perspective as a means of examining questions that suspend the semantic closure of the icons in question. They render the status of these icons multi-faceted or polysemic. They invite social questions rather than remaining solely on a formal level.

Moreover, whether the viewer would attempt to link the panels of either The Gates of Paradise or The Gates of Death to available biographic details of their artists or, alternatively, to a set of broader cultural questions, the panels activate such polemical parameters as icon versus form; image and substance; the interrelations of the verbal and the visual; class, art and politics; psychoanalysis; epistemology. These are discursive parameters that resist disciplinary partitions and call forth interdisciplinary approaches. In short, these parameters call forth such "social forces" as those to which James Saslow refers in the preceding citation.

Compared to the Isaac (middle left panel of Gates of Paradise), Genesis utilizes a rare instance of the presentation of depth through casamenti, an architectural setting, and the linear perspective attached to it. The Genesis relies on a 45 mm projection at the bottom of the panel and a 35 mm recession at the top. Such is the nature of the stage set in which the scale of the characters are somewhat proportionally depicted through their heights. The figures are composed in various sequences, which presume the illusion of space. The Isaac, on the other hand, depicts a fully worked out linear perspectival model. This panel utilizes architecture as a vital tool for a geometrically calculated presentation of depth through methods of linear perspective. Such a two-dimensional illusion of depth through architecture calls forth various linear geometric methods "invented" by Filippo Brunelleschi and later formulated by Leone Battista Alberti.

Richard Krautheimer6 describes the method through which an instance of Renaissance perspective has been put to use in The Gates of Paradise. Referring to the Isaac, which he contrasts with the Cain and Abel regarding its use of perspective, Krautheimer states that "Ghiberti's art and workmanship reached a climax [of perspectival technique]."7 As it is evident through a glance, the "complex and infinitely subtle composition is strengthened and indeed, made possible by the architectural setting which fills almost the entire height of the relief. A monumental hall with wide arches and tall pilasters underscores the successive events of the story, setting off the single scenes in separate spatial units and calling attention to the protagonists." 8 Krautheimer emphasizes three functions regarding the role of architecture and its use in the panel. First "it supports and clarifies the composition and narrative;" second, "since it follows a linear perspective, it contributes to the sense of a continuous all-embracing space;" and third, "it enables the spectator to measure distances, evaluate the relative size of figures and objects and clearly comprehend movements and relationships."9 In short, it is the use of architectural and to a certain extent geometrically calculated perspective to interweave narrative, depth and proportion that are evident in the Isaac.

|

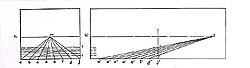

Yet there remain acute differences that set the pictorial composition of the Isaac apart from either the practice of Brunelleschi or the theories of Alberti read as being coherent or definitive. As Krautheimer's diagram of the Isaac demonstrates, there are a number of deviations from Alberti's fundamental elements of vanishing point, distance point, horizon, and so forth. The non-existence of a single or multiple vanishing points as indicated in Diagram 1 can be read as a non-adherence to a simplified Albertian model. As this model itself remains somewhat unstable, it has its own "gives and takes" as the reader moves from one part of Della pittura to another.10

|

Krautheimer concludes his analysis of linear perspective in The Gates of Paradise by noting their relation to the implementation of perspective through Brunelleschi's methods and Alberti's Della pittura. He assumes that "it is unlikely that he [Ghiberti] consciously tried to disregard Alberti's perspective construction. More likely he simply set out to reduce what he considered practical essentials." Referring to the extent to which Ghiberti put Alberti's perspectival theory into actual use, Krautheimer concludes his analysis of Ghiberti: "After all, his mind had never run along theoretical lines, and almost unaware he slipped out of Alberti's perspective system as suddenly as he had slipped into it."11

That slipping out of an established system on the part of Ghiberti, whether intentional or not, conscious or unconscious, can be read to activate a polemic within the domain of "the myth of Icarus" mentioned above. Such an approach calls forth the transformation of "text" into "context." Here, the objective and its illustration become for the producer and the spectator means of undoing the fixed. Setting aside Ghiberti's own

|

psychological parameters, one could pose the following query: Read from a broader standpoint, does the presence of multiple and non-singular vanishing points in Ghiberti's Isaac induce, to a certain extent, parallels to Brunelleschi's own departure from purely geometric, perspectival and hence ideally-stable formation of two-dimensional illusion of space? After all, it has been conjectured that Brunelleschi's formation of a stable illusion was activated through the insertion of the reflection of the sky on an area on the painting covered in silver leaf. The stabilized and idealized eye point and vanishing point through Brunelleschi's use of an apparatus were intended to provide the mirror reflection of an image so that the single "eye point" and the vanishing point were geometrically definable and precise. Yet the foreclosure of the device was transgressed through the instability of double reflections: a reflection of the still, painted picture which was to be destabilized through the "mirror" of a silver leaf echoing actual clouds of the sky. Damisch addresses the function of Brunelleschi's silver leaf by linking it to Lacan's "Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I" by interrogating:

But why the mirror? As opposed to the unweaned child who acknowledges the mirror image as his own, and who anticipates, through this form, the Gestalt or bodily integration and coordination it still lacks, the painter's image is not transformed by the specular reflection. With regard to unity, the kind of perspectival coherence characteristic of Brunelleschi's panel, which made it novel, had nothing imaginary about it, being the fruit of precise calculations and carefully considered decision: given a construction organized around a single point of view, the flat mirror did nothing but reverse its lateral orientation. But this reversal is not without its problems. For it would seem to provide support for the hypothesis that Brunelleschi executed his painting with the aid of a mirror, directly on a reflective surface, in which case he could have needed to use a second mirror to reestablish conformity with the order of things, as this image, having been constructed directly on a mirror reflection, would have effected an exchange of left for right and right for left. 12

Thus if the lineamenti (the schematic outlines), the misure (the means of representing reality), the ragioni (the proportionate relationships), and the casamenti and piani (the architectural settings) in the reliefs of The Gates of Paradise disobey the "scientific" rules of a physically fixed "gaze," it is because the semblance of reality could not be totally reduced to a purely Euclidean geometry; it is because pure geometry remains insufficient as a means of accounting for the image traced on the retina which resides within a pulsing body.

|

About four- to five-hundred years later perspective had come to either explicitly reverse itself or simply depart from the pictorial field in the West. As if a means of resisting illusion, the disintegration of three-dimensional space would become a companion of the partially dismembered figure in much of visual representation. Hence the figure would at times dissolve with the ground, as if to resist depth in order to turn its vantage point to the essential conditions of its own representation. The Gates of Death explicitly counteract depth through their own means, without a total departure from figures under the guise of icons. In fact, the unity of the figures would be undone through the submission of the index on them as such; these indexes are marks which were mere traces first incised on clay in order to be cast in bronze. The index is a semiotic term that has by now entered the discursive arena of art. It is as if the partial or total dissolution of the figure in the visual arts has necessitated an expansion of interpretive terms. Through the semiotic domain the term index has been marked as a category of signs apart from symbols and icons. As a large portion of twentieth-century art has eliminated definitive icons and symbols, setting forth material and form as content in many instances, the term index has been attached to the very physicality of marks and shapes within a given medium. Therefore, while the icon and the medium forming it were sides of the same coin during previous centuries, much Western art of the twentieth century, whether figurative or abstract, departs from the icon as such. It resists the closure of finite meanings. "Since things are as they are ("it is as it is, it is as it is," a formula dear to Kafka, marker of a state of facts), he will abandon sense, render it no more than implicit; he will retain only the skeleton of sense, or a paper cutout."13

Why, one may ask, does Death on Earth (lowermost right panel of Gates of Death) retain the presence of the figure, including a chair, draperies, the profile of a head and a crying child? Why does it undo the figure, extending certain physically negative and positive outlines of the figures, such as the curves emerging from the child's left hand? Or what is the visual function of an independent curve on the ground above the chest of the woman? Along with these floating lines there are also metallic "points" which are indexes of somewhat random and arbitrary frottages on clay during the initiation and casting of the relief. A direct departure from and the questioning of perspective remain marks of alternative directions of thought in the West. The dissolution of the figure and its ground as means of attaining the abstract can be read as partially linked to the individual of the machine age. Such an individual was also at the threshold of World War I. The abstractions of Mondrian or Malevich early in the century can be read as either partially detached from the social field or as signs of the infrastructures of certain ideologies-or both. The concepts linked to such works range from the total autonomy and self-justification of abstraction to its status as a symptom of prewar social conditions. Such conditions of labor have been identified under the rubric of technorationalism. These abstractions would be followed by partial returns to the figure in the works of Le Corbusier or Léger for example, whose organicism indicates a politically disturbing social field that had been traumatized by two World Wars.14 And the seemingly abstract output of a closer contemporary of Manzù, such as Lucio Fontana (Figure 3), seems to aim at a means of undoing the optical autonomy attached to the silence of the monochrome. If it undoes the silence and autonomy of the monochrome, it is through a "violent act" performed on the very canvas in order to render its material underbelly unmistakably "tangible" through sight. Yet unlike the abstract or "formless" means of representation which had come to characterize its century as a central visual direction, The Gates of Death of Manzù maintain the figure, only to negate it from within, through intentional incisions and accidental pores. Hence the accident here becomes a reciprocal parameter of the intentional.

To maintain, and yet to de-construct form, to represent death in space yet to undo the void of space through formless lumps and linear cavities which seem to echo rope parts, drapery, as well as nothingness-linear cavities as such: how are we to read these variants situated in an eloquent High Renaissance edifice, near a pair of Filarete doors? What is the abandonment of perspective here a sign of, given the availability of Alberti's Della pittura, Filarete's Treatise on Architecture and Brunelleschi's lessons as possible means of representing three-dimensional space through well-formulated architectural theories? What questions does Death in Space raise regarding the status of the twentieth-century artist who has departed from Alberti's or Filarete's techniques of visual representation of three-dimensional space?

"Once, religion had a power and a reality touching Dante and Michelangelo and others. At that time, dogmas, rites, symbols and images had real meaning for man and so, as a result, [they] did religious art which figured them. But today the images no longer speak the same way because life is elsewhere in science and the industrial revolution which has changed the world." 15 These were the sculptor's thoughts conveyed to Pope John XXIII during the time when the doors were being put forth in clay in Rome then being sent to Milan to be cast in bronze.

However, it would be misleading to reduce the Renaissance to mere dogma, rites and symbols in the visual filed, as put forth by Manzù above. Yet the romantic conception of selfhood hoped for in the past seems to have departed from the individual of the twentieth century. Or perhaps characterizing the past with a romantic conception of selfhood or the validity of religion had led many twentieth-century artists to depart from tradition to its fullest extent. If there was such a thing as "individual creative will," it was to reflect the very parameters of industrial labor that had entered the venue of art through such notions as seriality, repetition and depersonalization. Such an approach targets the end of material perfection within one of its most prohibited contexts in the Western world in this case-the façade of St. Peter's. From a semiotic standpoint, it would be the index that would function as a shifter, a destabilizing type of a sign that would abandon the space of perspective in order to render the icon itself polysemic. Here, the tactile conditions of the material would function as a rearticulated sign of what Diderot was to equip the blind man with in his "Letter of the Blind: For the Use of Those Who See." The fictive blind man would state: "it is touch that alerts us to the presence of certain modifications that remain imperceptible to the eyes until they have been informed of them by our sense of touch."16 And by linking the perspectival ideal to the sense of touch Lacan would render the categories of the two senses interdependent and de-stable. Instances of Lacan's discourse seem to be not unlike the words of Diderot's fictive blind man who said: "Yet we shall all pass one day, and without any possibility of measuring either the real space that we once occupied or the exact time that we have lived. Time, space, and matter are perhaps only a point."17 The Gates of Death, by destabilizing form through haptic disjunctions, open themselves up to the alienation of modern man: lonely, no longer with Christ and Madonna, but perhaps with Karl Marx.18 But even the role of Marx had come to signify the partial role of money in the self, no longer the only factor of alienation. Economics is a parameter that Lacan would add to the matrix of the unconscious conditioned by the visual and tactile. As if following the path of Diderot's blind man, Lacan would render time, space and matter as "points." He would do so through his use of an unsettled mode of speech and writing. The haziness of such a notion of "points" in certain ways parallels the alienation of the subject. Lacan presented his seminar on alienation on May 27, 1964, a month before the unveiling of The Gates of Death by Pope Paul VI-June 28, 1964.19

The slashes of the monochrome canvas of Lucio Fontana's Concetto Spaziale-Attese of 1963 pierce the totally abstracted high modernist myth of the purity of the monochrome. These cuts expunge the very coherence and stability of form at its most abstract. Here, the very tool of the index functions as a signifier whose signifieds would remain without a final interpretant. In The Gates of Death we witness slashes, cuts and bruises targeted toward the figure as well as toward the flat space surrounding and at times dissolving with parts of the figure. Its level of signification is thus rendered parallel to a numeric order that Lacan borrows from Descartes in order to illustrate the convolution of alienation: 20

1 + (1 + (1 + (1 + ( . . . )))).

Yet while Fontana's index violates the "purity" and autonomy of the monochrome flat within an unreligious context, Manzù's indexical marks were intentional violations of the "purity" of the flat, the icon and the figure within their most prohibited place-in the glory-laden shrine of the Eternal City. His mutilation of the figure renders the status of the Other a companion of the Self. The status quo of such a Self would remain incalculable, like the above cardinal order that Lacan selects. The Self and the Other would here become interchangeable companions of the Figurative and the Abstract.

In 1966 in Galleria La Salita in Rome, Richard Serra exhibited Live Animal Habitat. These were cages filled with live and stuffed animals. Such an approach was a means of departing from the two-dimensional and entering the realm of the real as such. Yet this was a realm with no finite beginning and end, but one of mere production as self-critique.21 This was another means of unveiling the disunity of the Self. The cultural implications of the physical piercing of the flat in order to give way to the formless upon The Gates of Death are various. One means of departing from the objective production of icons for Manzù was to state the status of the modern subject-uncertain of a whole self as such, having left behind the role of religion and that of theoretically established perspectival representation.

Once past the territory of the religious or the figurative icon, Death in Space, Death on Earth, Death of Abel, Death by Violence and the other panels could become replaced by new titles: Drawing the Line, Forging the Polis; Deterritorialization and the Withdrawal of the Line; Mass Society and the Collapse of Designo; The Line as Psychic Horizon; Lines without Subjects; Line as Pure Event; Field, Boundary, Consciousness. These were the titles of a lecture series entitled Lines of Sight: The Status of the Line in Modern Visual Representation that Norman Bryson held at Cooper Union in 1999. Contextually somewhat distant from The Gates of Death, these titles are nonetheless companions of The Gates of Death on a broader cultural level. The status of the line in much of modern visual representation is a departure from a systematic space marked by a horizon and a vanishing point. It is a means of "piercing" the flat not through illusion but through actual marks like those of the graffito artist, or through cuts such as Fontana's "signature." Line thus becomes a pure event, not only to undo the illusion of perspectival depth, but also to obliterate the notion of absolute purity and absolute flatness once attached to High Modernism. Such a means of representation can be read as an attempt to obliterate the notion of the unity of the Self as well.

And yet. The Gates of Death and The Gates of Paradise, despite their utter differences, both digress from systematization. If The Gates of Death are nonconforming to certain paradigms of their sanctified or temporal settings, it is because they adhere to neither the figure as a whole nor the abstract as such. They depart acutely from Albertian or aberrant depth as well. The panels of these doors have left the unity of the outlines and inner shapes of their figures vastly incomplete, as if to mirror the adamant resistance of the body to utter stability of any form-whether the corpus is alive, is taking its leave of life, or has become an inert corpse. The partial figure here thus becomes an "icon" of the corporeal self which continues to trade matter with its surrounding, whether this matter is air, food, light, or the causal agent of some other afferent or efferent activity. Such is the realm of Lacan's indeterminate object a. And The Gates of Paradise, despite their partial adoption of the costruzione legittima, deviate from the Albertian idealism of a geometrically determined single vanishing point in their own ways. To begin with, Brunelleschi's single-eye and stationary adherence to perspective was itself mediated through the instability of the sky obtained through the reflection on the silver leaf painted on his Baptistry panel in Florence. Here the motility of the image of the clouds becomes a conjugate to the dazzling, pulsatile blink of the eye. This blink remains inimical to purely systematized and stable norms of visuality. Alberti himself shifts in book II of Della pittura to warn the reader of the risks of the perspective paradigm. These risks are to a certain extent flattened in Ghiberti's rendition of perspective.

References:

1. Hubert Damisch, The Origin of Perspective (1987), trans. John Goodman (Cambridge, Mass. and London: MIT Press, 1994), p. 410. To assign the authorship of the Assisi frescoes to Giotto is questionable. One might read the allusion of Damisch to Giotto as a referential one rather than an attempt to address the quagmire of authorship per se. Regarding "the Assisi problem" see Giotto in Perspective, ed. Laurie Schneider (New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, 1974), pp. 14-16.

2. Referring to Giotto's contributions to illusionisitic depth, Lorenzo Ghiberti notes: "He brought forth naturalistic art and gracefulness with it never deviating from proportion. He was expert in all the arts, he was an inventor and discover of much theory which had lain buried for around 600 years." See Lorenzo Ghiberti, "The Commentari (c. 1450)," translated from I Commentari, vol. 2, edited by Ottavio Morisani (Naples: Riccardo Ricciardi, 1947), pp. 32-33, in Giotto in Perspective, ed. Laurie Schneider, pp. 39-40. In the "Introduction" to Giotto in Perspective Schneider notes: "For Ghiberti, it was Giotto rather than his and Alberti's contemporaries who spearheaded the Renaissance restoration of art. But like Alberti, he refrains from a discussion of perspective in connection with Giotto. In Ghiberti's view, Giotto deserves praise for his use of proper proportions-presumably the organic system based on the observation of nature." Schneider, ibid., p. 7.

3. Regarding the commonalities and differences between Euclidian optics and Renaissance perspective, see, for example, M.H. Pirenne, Optics, Paintings and Photography (London: Cambridge University Press, 1970), p. 148-149, referred to in Michael Podro, The Critical Historians of Art (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1982, 1991) pp. 187-189. See also Damisch, ibid., pp. 160-164 regarding the extent to which various Renaissance theorists and practitioners questioned the role of perspective within the realm of the ancients.

4. Damisch, pp. 262-263.

5. Laurie Schneider Adams, Art and Psychoanalysis (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), p. 86.

6. Richard Krautheimer, Lorenzo Ghiberti (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1982).

7. Ibid., p. 196.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. For example, referring to the interrelation of the vanishing point and the visible horizon Alberti writes: "For me this line is a limit above which no visible quantity is allowed unless it is higher than the eye of the beholder [literally: the eyes that see]. Because this line passes through the centric point, I call it the centric line." Alberti, quoted in Damisch, p. 386.

11. Ibid., p. 253.

12. Damisch, p. 117.

13. From Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature (1975), trans. Dana Polan (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), pp. 20-21.

14. For an analysis of modernist art as a counterpart of ideology see, for example, Romy Golan, Modernity and Nostalgia: Art and Politics in France Between the Wars (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1995).

15. Giacomo Manzù in Curtis Bill Pepper, An Artist and The Pope (London: Peter Davies, 1968), p. 108.

16. Denis Diderot, "Letter of the Blind: For the Use of Those Who See" (1789), in Diderot's Selected Writings, ed. Lester G. Croker, trans. Derek Coltman (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1966), p. 27.

17. Ibid., p. 23.

18. See Pepper, p. 30.

19. See Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Norton, 1977), p. 86, p. 92 on Diderot. Regarding life and money see "The Subject and the Other: Alienation," ibid., pp. 203-215.

20. Ibid., p. 225.

21. For an analysis of the work of Richard Serra in relation to "the depersonalizing conditions of industrial labor," see Rosalind Krauss, Richard Serra/Sculpture (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1986), pp. 15-38.

© 2000 Part and Raphy Sarkissian. All Rights Reserved.