| |

|

|

|

Rejection and recognition by the American Institute

of Architects (AIA) underscored the career of Buckminster Fuller

(1895-1983). Fuller claimed that in May 1928 the organization completely

dismissed the 4D House, his first project for a mass-produced, prefabricated

house. According to Fuller, the AIA's reaction to the 4D House was

so vicious that it immediately passed the following disclaimer:

"Be it resolved that the American Institute of Architects establish

itself on record as inherently opposed to any peas-in-a-pod-like

reproducible designs."1 However, forty-two years later in June

1970, the AIA awarded Fuller its gold medal especially for the geodesic

dome which was described in the citation as "the design of

the strongest, lightest and most efficient means of enclosing space

yet devised by man."2 In the interval between the AIA's dismissal

and acceptance of his work Fuller produced some other designs for

housing, of which the 1944-46 Dymaxion Dwelling Machine (popularly

called the Wichita House) is the most notable.3 Although the formal

properties of his housing designs were varied, most were circular

and Fuller's design concept for each was the same: use of industrial

processes and mass-produced, prefabricated, standardized components

to create living environments.4 In 1970 the AIA was ostensively

rewarding Fuller for his life's work, but, its emphasis was on Fuller's

innovative use of structure and materials, not the principles underlying

it nor his unconventional housing designs.

Fuller's insistence that industrial processes, not

aesthetics, control his design strategy places him in an unusual

position within twentieth century architecture.5 His

interest in applying industrial methods and standardization to housing

affirms his affinity to International Style architects, such as

Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, who also advocated

the use of mass-production and prefabrication in housing. Although

Gropius was the most active of these three in attempting to design

manufactured housing, Fuller considered him, as he did most architects,

to be an "exterior decorator" whose work "was trivial

since it did not seek to fulfill the need for shelter from an engineering

viewpoint, and without confirming to the demands of style or tradition."6

Fuller believed that industrial methods and standardization were

used primarily to package the house in a stylish envelope. With

the design of the Dymaxion House, he reconfigured the house it into

a radial plan with a metal and plastic exterior. Therefore, although

Fuller's attitude toward mass-production and prefabrication paralleled

the interests of International Style architects, his unusual design

concepts have prompted most historians to categorize them as fantasy

or futuristic architecture.7

Even though Fuller was not a trained architect,8

he did intend that his designs serve as practical solutions to housing

problems, not as imaginative exercises. As explained earlier, he

was disdainful of most architects because he felt that their approach

to housing was inhibited by their fidelity "to the demands

of style or tradition." In terms of housing, the only traditions

to which Fuller conformed were those of providing shelter and comfort.

He further believed that houses should enrich the lives of their

inhabitants. These guidelines motivated Fuller to conceptualize

the house as a demountable, radial container designed to facilitate

everyday life.9 His designs were intended to offer a feasible way

to apply the principles of industrial production to housing even

though they were not bound by the stylistic conventions of architecture

nor its history.

Fuller claimed he discovered how resistant "exterior

decorators" could be to his ideas in May 1928 when he presented

the 4D House to the AIA at its 61st convention in St. Louis.10 Fuller

was promoting the house as the answer to the need for affordable

housing and offered it as a complimentary gift to the association.

This was a generous but naive gesture since its design was amateurish

and awkward. The timing was also very bad because Milton Medary,

the AIA president, opened the convention with an address criticizing

"a growing tendency to standardize architectural design."11

In addition, the AIA board of directors released a report stating:

"It is quite possible that certain functions of the architect

may well become standardized, but what of the art of design? Can

one seriously consider the standardization of the drama, of literature,

of music, or arts kindred to our own such as painting and sculpture?

There is even now becoming evident in our work from coast to coast[...]a

universal product made to sell."12 Unfortunately for Fuller,

his 4D House was a design for a mass-produced, prefabricated home

"made to sell," precisely the type of structure the AIA

was strongly criticizing and publicly opposing. Even if the 4D House

had been a well-conceived design, given the opening statements of

its president, the AIA could not have accepted it. Fuller was disappointed

by the AIA's response but was not deterred from his goal of using

industry and technology to produce housing.

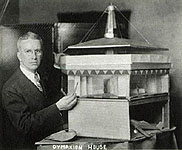

After the AIA convention, Fuller began a personal

crusade to accomplish this goal. He immediately self-published his

manifesto, 4D Time Lock, 1928,13 contacted the press and began to

draw upon his network of business contacts, friends, and supporters

to help promote his project.14 He redesigned the house and prepared

to take his idea directly to the public. During the preparations

for this launch the name of the house was changed from '4D' to 'Dymaxion'.15

A little less than one year after the convention, the redesigned

and renamed house was given its public debut in April 1929 at the

Marshall Field and Company department store in Chicago.16

There were few similarities between the designs

of the two houses. Both were to be industrially manufactured and

assembled from standardized components. In contrast to the fenestrated

walls of the 4D House, the walls of the Dymaxion House were transparent

plastic, fig. 1. Whereas 4D was a rectangular, two-story, central

mast house only slightly raised above the ground, the Marshall Field

model of the Dymaxion House was a hexagonal, one-story, central

mast structure suspended a full-floor above ground level and stabilized

with steel cables. The central mast, which was celebrated in the

Dymaxion House but seemed like an afterthought in the 4D House,

served as a utility core in both. Numerous household appliances

and mechanical systems were incorporated into each to make housework

less strenuous.17

These innovations were also incorporated into the

second model of the Dymaxion House which was made between sometime

between May 1929 and March 1930.18 Unlike the first rickety, paper

model, the sturdy new version was constructed of shiny aluminum

and transparent plastic; if manufactured the house was to be made

of inflatable duraluminum and casein, fig. 2. It was also sleeker

than the first model with a narrower living space supporting a roof

deck and covering a parking area.

|

|

|

Since it was of metal and looked machine-made, the

new model better illustrated Fuller's principles of mass-production,

prefabrication and industrial processes.19 He felt that

metal was the modern tool.20 He also believed that metal

should determine the processes of production and the approach to

design. Therefore, a house should be designed to have as many elements

as possible made of metal, shaped by a machine, prefabricated and

mass-produced. In other words, a house should be designed and produced

like a car out of factory-made parts. With the 1929 version of the

Dymaxion House Fuller had realized a more appropriate prototype

for the adaptation of industrial methods of production to housing.

Fuller, as previously stated, shared this interest

with many of his contemporaries although he disapproved of their

use of mass-production, prefabrication and industrial processes.

He was particularly critical towards the work of Gropius, Mies,

Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright. Although each had made important

contributions to housing by the late 1920s, Fuller thought they

failed to set new standards for both its design and production.

He believed that they, like most architects, relied upon the machine

to replicate or replace handwork; that they did not permit the machine

to control the construction process. Fuller thought they designed

with clean, simple forms which accommodated machine movement or

appeared to be machine-made and this was merely changing the appearance

of a building, not changing how it was made. He also felt they designed

with some prefabricated and standardized parts which were incorporated

into the finished structure, again affecting composition more than

method.21 To Fuller, such techniques added elements of

industrialization to the craft-labor construction process but were

technologically conservative and did not significantly alter it.

In Fuller's mind, Wright, Gropius, Mies and Corbusier were transferring

the hand-production based Arts and Crafts aesthetic of the 19th

century to machine production in the 20th. Their understanding of

architecture was based on education and on-the-job training unlike

Fuller who learned what he described as "craft building"22

as President of the Stockade Building System. This was a patented

system of construction using fibrous building blocks. Fuller formed

the company with his father-in-law, James Monroe Hewlett and was

its president from 1922 to 1927.23 In addition, Fuller

knew and read many important architectural texts of the time. His

practical experience was more limited than that of the architects

he criticized, but, in combination with his knowledge of contemporary

writing, it fueled his ambition to apply industrial methods to the

housing industry.

|

|

|

Fuller did not credit his reading with being as

significant as his practical experience. Yet, the unpublished reference

list for 4D Time Lock is a lengthy roster of important writings,

fig. 3. There are no references to Mies and Gropius, but, the 1927

English edition of Corbusier's Towards a New Architecture

and Wright's essay "What "Styles" Mean to the Architect,"

Architectural Record, February 1928, are included.24

Given Fuller's insistence that Wright was privileging style over

process, it is surprising that Fuller does not list Wright's essay

"Art and Craft of the Machine," 1901. In this essay Wright

argued that the machine be used to free the artist from the drudgery

of handwork. He thought it was fine to use the machine to produce

the components of a building but the design and appearance should

still be determined by the architect's aesthetic sensibilities.25

Wright reinforced this argument in "What "Styles"

Mean to the Architect" by claiming standardization serves as

the impersonal structure with which the architect's personal style

should be integrated. He wrote: "standardization[...]serves

as a kind of warp on which to weave the woof of[...]building."26

In contrast, Fuller proposed that standardization should serve as

the basis for both the structure and design of a building. Although

there are similarities in their approaches, Wright and Fuller differed

in their assessments of the role industrial methods should play

in architecture. Fuller's inclusion of "What "Styles"

Mean to the Architect" in his reference list may have been

to demonstrate that his own theory of design was related to, but

different from, the philosophy of one of architecture's leaders.

This may also have been Fuller's motivation for

including Corbusier's Towards a New Architecture on the reference

list. Unlike "What "Styles" Mean to the Architect,"

Fuller provides an evaluation of this source in a letter he wrote

to his sister Rosamond on August 11, 1928. In it he claimed that

he and Corbusier have almost "identical phraseology."

He wrote that Corbusier was:

"the great revolutionist in architectural

design whose book should be read in conjunction with my 4D. My

own reading of Corbusier's "Towards a New Architecture",

at the time when I was writing my own, nearly stunned me by the

almost identical phraseology of his telegraphic style of notion

with the notations of my own set down completely from my own intuitive

searching and reasoning and unaware even of the existence of such

a man as Corbusier. Corusier [sic] was first called to my attention

by Russell Walcott, the best of residential designers in Chicago,

when I was explaining my principles to him last November."27

Walcott may have told Fuller about Corbusier in

November 1927, but, he lent Fuller Towards A New Architecture

the following January. Fuller dutifully noted the act in his diary

on January 30, 1928: "Called on Russell Walcott and borrowed

Le Corbusier's "Towards the New Architecture"[...]RBF

read Le Corbusier until very late at night. Startled at coincidence

of results arrived at in comparison to Fuller Houses but misses

main philosophy of home as against house."28 Although Fuller

was criticizing Corbusier for being interested more in the formal

properties of a house than in accommodating the activities that

make it a home, he empathized with Corbusier's philosophy.29

Whether resulting from "identical phraseology"

or direct influence, there are numerous similarities between the

ideas presented in 4D Time Lock and Towards A New Architecture.30

Each book called for the use of standardization, prefabrication

and mass-production in the building industry. Furthermore, both

referred to the automobile industry as a prototype. Fuller often

used the analogy of automobile production to support his argument

that houses should be mass-produced and not custom-designed. According

to him, the cost per automobile decreases as more cars are manufactured

which allows the manufacturer to price products according to make

and model. He wanted to apply this method to housing. Corbusier,

on the other hand, included the idea as almost an offhand comment

and without elaboration or instructions. He simply wrote: "I

am 40 years old, why should I not buy a house for myself? for I

need this instrument; a house built on the same principles as the

Ford car I bought (or my Citroen, if I am particular)."31

Corbusier's comment is so subtle that it is difficult to link it

to Fuller's developed argument. Fuller, however, found an corresponding

idea in Corbusier's short recommendation.

Corbusier also briefly alluded to another one of

Fuller's major points: the need to reduce the weight of buildings.

Fuller recommended that the weight of buildings be decreased in

order to lower costs and waste. He repeatedly argues this throughout

4D Time Lock and devotes an entire chapter to the subject, Chapter

Nine: Weight in Building as the New Economical Factor. Corbusier,

in the caption for Le Corbusier, 1919, A "Monol"

House succinctly states that "the ordinary house weighs

too much".32 The similarity in their thinking is clearer in

this case although the degree to which they dealt with the subject

is again different.

They both believed machines would increasingly be

used in the home to make housework easier, but, they disagreed about

who would reap the benefits. Fuller included mechanical appliances

to ease the drudgery of housekeeping and supply the housewife with

dutiful and competent mechanical servants. He thought mechanical

appliances would replace servants. Corbusier thought machines would

make it possible for servants to work in shifts, like factory workers.

He wrote: "Modern achievement[...]replaces human labour by

the machine and by good organization[...]Servants are no longer

of necessity tied to the house: they come here, as they would a

factory, and do their eight hours; in this way an active staff is

available day and night."33 In terms of mechanical appliances,

Fuller and Corbusier are proposing dissimilar applications for similar

technology.

Not surprisingly, they also meant different things

when they proclaimed the need for a new architecture to meet the

needs of modern life. Corbusier wanted to make a "machine for

living in" by using machine processes to achieve aesthetic

results that would please the inhabitant. Fuller wanted a "machine

for living," a house that would function like a machine to

improve the quality of the life of its inhabitants.34 Corbusier

wanted to use machine made parts like puzzle pieces to create a

whole whereas Fuller wanted the machine to serve as a model of efficiency.

Corbusier wanted modern architecture to serve as a stage for modern

life; Fuller wanted modern architecture to facilitate modern life.

Fuller and Corbusier were working with related ideas

in their programs for the modern house. But, as the previous comparisons

have shown, they varied in their application and expression of these

ideas. These programs, therefore, led to different possibilities

for architecture as Reyner Banham explained in Theory and Design

in the First Machine Age. He wrote:

"Fuller had advanced, in his Dymaxion House

project, a concept of domestic design that[...]had it been built,

would have rendered [Corbusier's designs...] technically obsolete

before design had even begun[...]The formal qualities of [the

Dymaxion House] are not remarkable, except in combination with

the structural and planning methods involved. The structure does

not derive from the imposition of a[n...] aesthetic on a material

that has been elevated to the level of a symbol for 'the machine'[...]The

planning derives from a liberated attitude to those mechanical

services that had precipated the whole Modern adventure by their

invasion of homes and streets before 1914."35

Banham saw in the Dymaxion House potential for a

new type of architecture and in Corbusier's housing designs he found

the updating of existing architectural conventions. Despite their

differences there are still similarities found in their 1920s projects

which demonstrate how easily Fuller could be "[s]tartled at

coincidence of results arrived at in comparison to Fuller Houses"

in Corbusier's book.

|

|

|

There are also "startling coincidences of results"

found by comparing the mature design of the Dymaxion House to Corbusier's

Villa Savoye, Poissy, France, 1928-29, fig. 4.36 In each

house the main living area is raised off the ground although Corbusier

used pilotis and Fuller used a central mast. Both houses have horizontal

strip windows but Corbusier treats them like traditional fenestration

which is set into the wall unlike Fuller who treats them as major

components of the wall. Because there is a structural frame in each

house the walls are not load-bearing and the facades free. The roof

of each is utilized: Corbusier transformed it into a roof garden

and Fuller converted it into an upper deck. The houses do, however,

differ in their plans. Corbusier used an orthogonal footprint with

rectangular rooms that connect to one another; Fuller used a radial

plan with triangular rooms that are accessed either at the central

mast or along the outer wall. Thus, although the configuration of

the homes are not alike, many components are treated similarly.

Whether this resulted from coincidence or influence

is difficult to determine. With the exception of the central mast,

Fuller completely reconfigured his design between its May 1928 presentation

to the AIA and the April 1929 exhibition at Marshall Field. Furthermore,

it was also drastically redesigned during the production of the

second model before March 1930. According to his diary, Fuller read

Towards A New Architecture in January 1928 before any of

the designs were formulated. The 1929 version more clearly reflected

Fuller's ideological program for the house: that it should be prefabricated

and mass-produced as well as facilitate the lives of the inhabitants.37

The new model may also have been intended to illustrate that Fuller

knew of contemporary developments in housing design and that he

was correcting what he considered to be their shortcomings. Therefore,

by designing a house that drew upon current debates (role of the

machine, standardization and mass-production in housing) and also

drew upon concurrent aesthetics (raising the living areas above

the ground, recreational use of the roof and window walls), Fuller

was demonstrating his understanding of and desire to improve contemporary

design and architectural theory.

There are two other characteristics of the Dymaxion

House which can serve as concluding points of difference and similarity

between Fuller's house and the designs of his colleagues. These

are mobility and assembly. The Dymaxion House was designed to be

mobile in the sense that it could be taken apart, shipped to a new

location and reassembled. Fuller believed mobility represented a

number of ideals including time as the new currency, industrial

production, reduced weight and the American spirit of individualism

and freedom. Although Fuller considered mobility to be an important

consideration of modern housing, he did not design the house to

be transported as a unit. In a process which would have been both

inconvenient and time-consuming, the house was designed to be taken

apart, crated, shipped to the new location and re-assembled.

The method of moving the house was the same as that

specified for its delivery from the factory to its original location.

The components of the Dymaxion House were designed to be mass-produced

and prefabricated in a factory. Then, they were to be crated, shipped

to the site and assembled by hand. This is a strange paradox since

Fuller insisted upon machine production and allowing industrial

processes to determine the design strategy, but, he maintained the

traditional reliance upon craft labor to assemble the various components

of the house into a finished building. It is also in contrast to

his argument that "craft building[...]is an art which belongs

in the middle ages."38 Fuller, however, believed

he needed to use craft labor on site because he thought shipping

the assembled house was impractical. He wrote:

"Of importance[...]was the problem of transporting

large units of structure[...]entire houses and apartment houses

must be constructed in factories and delivered as totally assembled

products, like automobiles. But with existing transportation facilities,

no house can be moved more than a few miles. It is not practicable

[sic] to load a house on a flatcar or a trailer and transport

it through city streets, under and over bridges, and through tunnels.

It is theoretically possible, to deliver a full-size, pre-assembled

house by air."39

Although Fuller's decision to ship the house as

a kit was based on practical considerations, it was also similar

to the role that Mies van der Rohe thought mass-production and prefabrication

would play in the housing industry. In 1924 Mies predicted that

"industrial production of all the parts can really be rationalized

only in the course of the manufacturing process, and work on the

site will be entirely a matter of assembly."40 It is doubtful

Fuller would have known of Mies' prediction since it was published

in the German magazine G.41 While Fuller and Mies were

considering the issues of construction from two different vantage

points, their conclusions are remarkably similar. This may have

resulted from their common knowledge of architectural theory or

it may have been another instance of "startling coincidences

of results."

|

|

|

Despite the "startling coincidences of results,"

Fuller believed Mies and other architects of the 1920s did not fully

explore the potentials of the machine and industrial production

in their housing designs. Buckminster Fuller believed the only way

to design houses was to do so according to industrial methods of

production and machine processes. In addition, he espoused that

materials appropriate for industrial production, especially metal

and plastic, were to be used. He established these criteria between

1928 and 1929 in the development of his first project for a mass-produced

house, the 4D/Dymaxion House. These criteria were the foundation

upon which Fuller built his design strategy for housing. This was

a strategy based upon production, not aesthetics. As he wrote in

4D Time Lock, "nostalgia for past values and aesthetics

are not allowed to interfere with the industrially produced house."42

Fuller was proclaiming that new methods of production would produce

a new type of modern housing with its own system of aesthetics,

reflecting its time and methods of production without being tethered

to those of the past.

Sources>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|