Buckminster

Fuller - Dialogue with Modernism

by Loretta Lorance

|

|

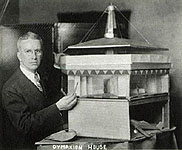

Fig 1:

1920s postcard of Buckminster Fuller with first model of the Dymaxion

House, no date, approx. 3.5" x 5";

Courtesy, The Estate of Buckminster Fuller, Sebastopol, CA and Courtesy of Department of Special Collections, Stanford Universities Libraries, Stanford, CA. |

Rejection and recognition by the American Institute of Architects (AIA) underscored the career of Buckminster Fuller (1895-1983). Fuller claimed that in May 1928 the organization completely dismissed the 4D House, his first project for a mass-produced, prefabricated house. According to Fuller, the AIA's reaction to the 4D House was so vicious that it immediately passed the following disclaimer: "Be it resolved that the American Institute of Architects establish itself on record as inherently opposed to any peas-in-a-pod-like reproducible designs."1 However, forty-two years later in June 1970, the AIA awarded Fuller its gold medal especially for the geodesic dome which was described in the citation as "the design of the strongest, lightest and most efficient means of enclosing space yet devised by man."2 In the interval between the AIA's dismissal and acceptance of his work Fuller produced some other designs for housing, of which the 1944-46 Dymaxion Dwelling Machine (popularly called the Wichita House) is the most notable.3 Although the formal properties of his housing designs were varied, most were circular and Fuller's design concept for each was the same: use of industrial processes and mass-produced, prefabricated, standardized components to create living environments.4 In 1970 the AIA was ostensively rewarding Fuller for his life's work, but, its emphasis was on Fuller's innovative use of structure and materials, not the principles underlying it nor his unconventional housing designs.

Fuller's insistence that industrial processes, not aesthetics, control his design strategy places him in an unusual position within twentieth century architecture.5 His interest in applying industrial methods and standardization to housing affirms his affinity to International Style architects, such as Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius and Le Corbusier, who also advocated the use of mass-production and prefabrication in housing. Although Gropius was the most active of these three in attempting to design manufactured housing, Fuller considered him, as he did most architects, to be an "exterior decorator" whose work "was trivial since it did not seek to fulfill the need for shelter from an engineering viewpoint, and without confirming to the demands of style or tradition."6 Fuller believed that industrial methods and standardization were used primarily to package the house in a stylish envelope. With the design of the Dymaxion House, he reconfigured the house it into a radial plan with a metal and plastic exterior. Therefore, although Fuller's attitude toward mass-production and prefabrication paralleled the interests of International Style architects, his unusual design concepts have prompted most historians to categorize them as fantasy or futuristic architecture.7

Even though Fuller was not a trained architect,8 he did intend that his designs serve as practical solutions to housing problems, not as imaginative exercises. As explained earlier, he was disdainful of most architects because he felt that their approach to housing was inhibited by their fidelity "to the demands of style or tradition." In terms of housing, the only traditions to which Fuller conformed were those of providing shelter and comfort. He further believed that houses should enrich the lives of their inhabitants. These guidelines motivated Fuller to conceptualize the house as a demountable, radial container designed to facilitate everyday life.9 His designs were intended to offer a feasible way to apply the principles of industrial production to housing even though they were not bound by the stylistic conventions of architecture nor its history.

Fuller claimed he discovered how resistant "exterior decorators" could be to his ideas in May 1928 when he presented the 4D House to the AIA at its 61st convention in St. Louis.10 Fuller was promoting the house as the answer to the need for affordable housing and offered it as a complimentary gift to the association. This was a generous but naive gesture since its design was amateurish and awkward. The timing was also very bad because Milton Medary, the AIA president, opened the convention with an address criticizing "a growing tendency to standardize architectural design."11 In addition, the AIA board of directors released a report stating: "It is quite possible that certain functions of the architect may well become standardized, but what of the art of design? Can one seriously consider the standardization of the drama, of literature, of music, or arts kindred to our own such as painting and sculpture? There is even now becoming evident in our work from coast to coast[...]a universal product made to sell."12 Unfortunately for Fuller, his 4D House was a design for a mass-produced, prefabricated home "made to sell," precisely the type of structure the AIA was strongly criticizing and publicly opposing. Even if the 4D House had been a well-conceived design, given the opening statements of its president, the AIA could not have accepted it. Fuller was disappointed by the AIA's response but was not deterred from his goal of using industry and technology to produce housing.

After the AIA convention, Fuller began a personal crusade to accomplish this goal. He immediately self-published his manifesto, 4D Time Lock, 1928,13 contacted the press and began to draw upon his network of business contacts, friends, and supporters to help promote his project.14 He redesigned the house and prepared to take his idea directly to the public. During the preparations for this launch the name of the house was changed from '4D' to 'Dymaxion'.15 A little less than one year after the convention, the redesigned and renamed house was given its public debut in April 1929 at the Marshall Field and Company department store in Chicago.16

There were few similarities between the designs of the two houses. Both were to be industrially manufactured and assembled from standardized components. In contrast to the fenestrated walls of the 4D House, the walls of the Dymaxion House were transparent plastic, fig. 1. Whereas 4D was a rectangular, two-story, central mast house only slightly raised above the ground, the Marshall Field model of the Dymaxion House was a hexagonal, one-story, central mast structure suspended a full-floor above ground level and stabilized with steel cables. The central mast, which was celebrated in the Dymaxion House but seemed like an afterthought in the 4D House, served as a utility core in both. Numerous household appliances and mechanical systems were incorporated into each to make housework less strenuous.17

These innovations were also incorporated into the second model of the Dymaxion House which was made between sometime between May 1929 and March 1930.18 Unlike the first rickety, paper model, the sturdy new version was constructed of shiny aluminum and transparent plastic; if manufactured the house was to be made of inflatable duraluminum and casein, fig. 2. It was also sleeker than the first model with a narrower living space supporting a roof deck and covering a parking area.

|

|

Fig 2:

Photograph of the second model of the Dymaxion House, no date, approx.

5" x 7"; Courtesy, The Estate of Buckminster Fuller, Sebastopol,

CA and Courtesy of Department of Special Collections, Stanford Universities

Libraries, Stanford, CA.

|

Since it was of metal and looked machine-made, the new model better illustrated Fuller's principles of mass-production, prefabrication and industrial processes.19 He felt that metal was the modern tool.20 He also believed that metal should determine the processes of production and the approach to design. Therefore, a house should be designed to have as many elements as possible made of metal, shaped by a machine, prefabricated and mass-produced. In other words, a house should be designed and produced like a car out of factory-made parts. With the 1929 version of the Dymaxion House Fuller had realized a more appropriate prototype for the adaptation of industrial methods of production to housing.

Fuller, as previously stated, shared this interest with

many of his contemporaries although he disapproved of their use of mass-production,

prefabrication and industrial processes. He was particularly critical

towards the work of Gropius, Mies, Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright. Although

each had made important contributions to housing by the late 1920s, Fuller

thought they failed to set new standards for both its design and production.

He believed that they, like most architects, relied upon the machine to

replicate or replace handwork; that they did not permit the machine to

control the construction process. Fuller thought they designed with clean,

simple forms which accommodated machine movement or appeared to be machine-made

and this was merely changing the appearance of a building, not changing

how it was made. He also felt they designed with some prefabricated and

standardized parts which were incorporated into the finished structure,

again affecting composition more than method.21 To Fuller,

such techniques added elements of industrialization to the craft-labor

construction process but were technologically conservative and did not

significantly alter it. In Fuller's mind, Wright, Gropius, Mies and Corbusier

were transferring the hand-production based Arts and Crafts aesthetic

of the 19th century to machine production in the 20th. Their understanding

of architecture was based on education and on-the-job training unlike

Fuller who learned what he described as "craft building"22

as President of the Stockade Building System. This was a patented system

of construction using fibrous building blocks. Fuller formed the company

with his father-in-law, James Monroe Hewlett and was its president from

1922 to 1927.23 In addition, Fuller knew and read many important

architectural texts of the time. His practical experience was more limited

than that of the architects he criticized, but, in combination with his

knowledge of contemporary writing, it fueled his ambition to apply industrial

methods to the housing industry.

|

|

Fig 3:

Page 3 of unpublished reference list for 4D TimeLock, 1928.

Fuller has numbered this both E-300 and 94. The R. Buckminster Fuller

Papers, Series 2, Chronofile, Vol. 34, Courtesy of Department of

Special Collections, Stanford Universities Libraries, Stanford,

CA.

|

Fuller did not credit his reading with being as significant as his practical experience. Yet, the unpublished reference list for 4D Time Lock is a lengthy roster of important writings, fig. 3. There are no references to Mies and Gropius, but, the 1927 English edition of Corbusier's Towards a New Architecture and Wright's essay "What "Styles" Mean to the Architect," Architectural Record, February 1928, are included.24 Given Fuller's insistence that Wright was privileging style over process, it is surprising that Fuller does not list Wright's essay "Art and Craft of the Machine," 1901. In this essay Wright argued that the machine be used to free the artist from the drudgery of handwork. He thought it was fine to use the machine to produce the components of a building but the design and appearance should still be determined by the architect's aesthetic sensibilities.25 Wright reinforced this argument in "What "Styles" Mean to the Architect" by claiming standardization serves as the impersonal structure with which the architect's personal style should be integrated. He wrote: "standardization[...]serves as a kind of warp on which to weave the woof of[...]building."26 In contrast, Fuller proposed that standardization should serve as the basis for both the structure and design of a building. Although there are similarities in their approaches, Wright and Fuller differed in their assessments of the role industrial methods should play in architecture. Fuller's inclusion of "What "Styles" Mean to the Architect" in his reference list may have been to demonstrate that his own theory of design was related to, but different from, the philosophy of one of architecture's leaders.

This may also have been Fuller's motivation for including Corbusier's Towards a New Architecture on the reference list. Unlike "What "Styles" Mean to the Architect," Fuller provides an evaluation of this source in a letter he wrote to his sister Rosamond on August 11, 1928. In it he claimed that he and Corbusier have almost "identical phraseology." He wrote that Corbusier was:

"the great revolutionist in architectural design whose book should be read in conjunction with my 4D. My own reading of Corbusier's "Towards a New Architecture", at the time when I was writing my own, nearly stunned me by the almost identical phraseology of his telegraphic style of notion with the notations of my own set down completely from my own intuitive searching and reasoning and unaware even of the existence of such a man as Corbusier. Corusier [sic] was first called to my attention by Russell Walcott, the best of residential designers in Chicago, when I was explaining my principles to him last November."27

Walcott may have told Fuller about Corbusier in November 1927, but, he lent Fuller Towards A New Architecture the following January. Fuller dutifully noted the act in his diary on January 30, 1928: "Called on Russell Walcott and borrowed Le Corbusier's "Towards the New Architecture"[...]RBF read Le Corbusier until very late at night. Startled at coincidence of results arrived at in comparison to Fuller Houses but misses main philosophy of home as against house."28 Although Fuller was criticizing Corbusier for being interested more in the formal properties of a house than in accommodating the activities that make it a home, he empathized with Corbusier's philosophy.29

Whether resulting from "identical phraseology" or direct influence, there are numerous similarities between the ideas presented in 4D Time Lock and Towards A New Architecture.30 Each book called for the use of standardization, prefabrication and mass-production in the building industry. Furthermore, both referred to the automobile industry as a prototype. Fuller often used the analogy of automobile production to support his argument that houses should be mass-produced and not custom-designed. According to him, the cost per automobile decreases as more cars are manufactured which allows the manufacturer to price products according to make and model. He wanted to apply this method to housing. Corbusier, on the other hand, included the idea as almost an offhand comment and without elaboration or instructions. He simply wrote: "I am 40 years old, why should I not buy a house for myself? for I need this instrument; a house built on the same principles as the Ford car I bought (or my Citroen, if I am particular)."31 Corbusier's comment is so subtle that it is difficult to link it to Fuller's developed argument. Fuller, however, found an corresponding idea in Corbusier's short recommendation.

Corbusier also briefly alluded to another one of Fuller's major points: the need to reduce the weight of buildings. Fuller recommended that the weight of buildings be decreased in order to lower costs and waste. He repeatedly argues this throughout 4D Time Lock and devotes an entire chapter to the subject, Chapter Nine: Weight in Building as the New Economical Factor. Corbusier, in the caption for Le Corbusier, 1919, A "Monol" House succinctly states that "the ordinary house weighs too much".32 The similarity in their thinking is clearer in this case although the degree to which they dealt with the subject is again different.

They both believed machines would increasingly be used in the home to make housework easier, but, they disagreed about who would reap the benefits. Fuller included mechanical appliances to ease the drudgery of housekeeping and supply the housewife with dutiful and competent mechanical servants. He thought mechanical appliances would replace servants. Corbusier thought machines would make it possible for servants to work in shifts, like factory workers. He wrote: "Modern achievement[...]replaces human labour by the machine and by good organization[...]Servants are no longer of necessity tied to the house: they come here, as they would a factory, and do their eight hours; in this way an active staff is available day and night."33 In terms of mechanical appliances, Fuller and Corbusier are proposing dissimilar applications for similar technology.

Not surprisingly, they also meant different things when they proclaimed the need for a new architecture to meet the needs of modern life. Corbusier wanted to make a "machine for living in" by using machine processes to achieve aesthetic results that would please the inhabitant. Fuller wanted a "machine for living," a house that would function like a machine to improve the quality of the life of its inhabitants.34 Corbusier wanted to use machine made parts like puzzle pieces to create a whole whereas Fuller wanted the machine to serve as a model of efficiency. Corbusier wanted modern architecture to serve as a stage for modern life; Fuller wanted modern architecture to facilitate modern life.

Fuller and Corbusier were working with related ideas in their programs for the modern house. But, as the previous comparisons have shown, they varied in their application and expression of these ideas. These programs, therefore, led to different possibilities for architecture as Reyner Banham explained in Theory and Design in the First Machine Age. He wrote:

"Fuller had advanced, in his Dymaxion House project, a concept of domestic design that[...]had it been built, would have rendered [Corbusier's designs...] technically obsolete before design had even begun[...]The formal qualities of [the Dymaxion House] are not remarkable, except in combination with the structural and planning methods involved. The structure does not derive from the imposition of a[n...] aesthetic on a material that has been elevated to the level of a symbol for 'the machine'[...]The planning derives from a liberated attitude to those mechanical services that had precipated the whole Modern adventure by their invasion of homes and streets before 1914."35

Banham saw in the Dymaxion House potential for a new type of architecture and in Corbusier's housing designs he found the updating of existing architectural conventions. Despite their differences there are still similarities found in their 1920s projects which demonstrate how easily Fuller could be "[s]tartled at coincidence of results arrived at in comparison to Fuller Houses" in Corbusier's book.

|

|

Fig 4:

Le Corbusier, Villa Savoye, Poissy, France, 1928-29. Digital photograph

courtesy of Virginia Smith, New York, NY, 1999.

|

There are also "startling coincidences of results" found by comparing the mature design of the Dymaxion House to Corbusier's Villa Savoye, Poissy, France, 1928-29, fig. 4.36 In each house the main living area is raised off the ground although Corbusier used pilotis and Fuller used a central mast. Both houses have horizontal strip windows but Corbusier treats them like traditional fenestration which is set into the wall unlike Fuller who treats them as major components of the wall. Because there is a structural frame in each house the walls are not load-bearing and the facades free. The roof of each is utilized: Corbusier transformed it into a roof garden and Fuller converted it into an upper deck. The houses do, however, differ in their plans. Corbusier used an orthogonal footprint with rectangular rooms that connect to one another; Fuller used a radial plan with triangular rooms that are accessed either at the central mast or along the outer wall. Thus, although the configuration of the homes are not alike, many components are treated similarly.

Whether this resulted from coincidence or influence is difficult to determine. With the exception of the central mast, Fuller completely reconfigured his design between its May 1928 presentation to the AIA and the April 1929 exhibition at Marshall Field. Furthermore, it was also drastically redesigned during the production of the second model before March 1930. According to his diary, Fuller read Towards A New Architecture in January 1928 before any of the designs were formulated. The 1929 version more clearly reflected Fuller's ideological program for the house: that it should be prefabricated and mass-produced as well as facilitate the lives of the inhabitants.37 The new model may also have been intended to illustrate that Fuller knew of contemporary developments in housing design and that he was correcting what he considered to be their shortcomings. Therefore, by designing a house that drew upon current debates (role of the machine, standardization and mass-production in housing) and also drew upon concurrent aesthetics (raising the living areas above the ground, recreational use of the roof and window walls), Fuller was demonstrating his understanding of and desire to improve contemporary design and architectural theory.

There are two other characteristics of the Dymaxion House which can serve as concluding points of difference and similarity between Fuller's house and the designs of his colleagues. These are mobility and assembly. The Dymaxion House was designed to be mobile in the sense that it could be taken apart, shipped to a new location and reassembled. Fuller believed mobility represented a number of ideals including time as the new currency, industrial production, reduced weight and the American spirit of individualism and freedom. Although Fuller considered mobility to be an important consideration of modern housing, he did not design the house to be transported as a unit. In a process which would have been both inconvenient and time-consuming, the house was designed to be taken apart, crated, shipped to the new location and re-assembled.

The method of moving the house was the same as that specified for its delivery from the factory to its original location. The components of the Dymaxion House were designed to be mass-produced and prefabricated in a factory. Then, they were to be crated, shipped to the site and assembled by hand. This is a strange paradox since Fuller insisted upon machine production and allowing industrial processes to determine the design strategy, but, he maintained the traditional reliance upon craft labor to assemble the various components of the house into a finished building. It is also in contrast to his argument that "craft building[...]is an art which belongs in the middle ages."38 Fuller, however, believed he needed to use craft labor on site because he thought shipping the assembled house was impractical. He wrote:

"Of importance[...]was the problem of transporting large units of structure[...]entire houses and apartment houses must be constructed in factories and delivered as totally assembled products, like automobiles. But with existing transportation facilities, no house can be moved more than a few miles. It is not practicable [sic] to load a house on a flatcar or a trailer and transport it through city streets, under and over bridges, and through tunnels. It is theoretically possible, to deliver a full-size, pre-assembled house by air."39

Although Fuller's decision to ship the house as a kit was based on practical considerations, it was also similar to the role that Mies van der Rohe thought mass-production and prefabrication would play in the housing industry. In 1924 Mies predicted that "industrial production of all the parts can really be rationalized only in the course of the manufacturing process, and work on the site will be entirely a matter of assembly."40 It is doubtful Fuller would have known of Mies' prediction since it was published in the German magazine G.41 While Fuller and Mies were considering the issues of construction from two different vantage points, their conclusions are remarkably similar. This may have resulted from their common knowledge of architectural theory or it may have been another instance of "startling coincidences of results."

|

|

Fig 5:

Anne Hewlett Fuller, Untitled Painting of Dymaxion House and

Dymaxion Car, no date, approx. 24" x 36"; Courtesy,

The Estate of Buckminster Fuller, Sebastopol, CA and Courtesy of

Department of Special Collections, Stanford Universities Libraries,

Stanford, CA.

|

Despite the "startling coincidences of results," Fuller believed Mies and other architects of the 1920s did not fully explore the potentials of the machine and industrial production in their housing designs. Buckminster Fuller believed the only way to design houses was to do so according to industrial methods of production and machine processes. In addition, he espoused that materials appropriate for industrial production, especially metal and plastic, were to be used. He established these criteria between 1928 and 1929 in the development of his first project for a mass-produced house, the 4D/Dymaxion House. These criteria were the foundation upon which Fuller built his design strategy for housing. This was a strategy based upon production, not aesthetics. As he wrote in 4D Time Lock, "nostalgia for past values and aesthetics are not allowed to interfere with the industrially produced house."42 Fuller was proclaiming that new methods of production would produce a new type of modern housing with its own system of aesthetics, reflecting its time and methods of production without being tethered to those of the past.

Notes

1. R.B. Fuller and R. Marks, The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, Garden City, NY: Anchor Books, 1973, p. 20. In Volume 35 of the Chronofile, Fuller's collected personal papers, there is an article outlining the AIA's strong stance against standardization of architectural design, Cities Becoming 'Peas of One Pod,' Architects Warn, dated May 17, 1928, from the St. Louis Star. Fuller claimed that he presented the house on May 16 at the AIA's annual meeting in St. Louis. Neither Fuller nor the Dymaxion House are mentioned in it. (Chronofile, Volume 35, 1928, The R. Buckminster Fuller Papers, Stanford University, Stanford, CA)

2. Citation as reprinted in Richard Guy Wilson, The AIA Gold Medal, New York: McGraw Hill Book Company, 1984, p. 210.

3. For a complete inventory of Fuller's housing designs see James Ward, ed., The Artifacts of Buckminster Fuller, New York: Garland Publishing, 1985. Two other excellent sources for Fuller's housing designs are J. Baldwin, BuckyWorks: Buckminster Fuller's Ideas for Today, New York: J. Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1996, and The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller.

4. The 4D House is, by nature, a living environment. This aspect of the geodesic dome is often overlooked since it is usually employed for industrial or commercial applications. Fuller considered the geodesic dome to be an environmental valve that could "envelop living quarters, gardens, lawns, acres or cities" and could cause "the conventional house to become, if not obsolete, at least increasingly superfluous." (The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, p. 65)

5. In the introduction to Forget Fuller?, ANY No. 17, Reinhold Martin describes the ambivalent attitude of the architectural profession toward Fuller: "The architectural establishment treated Fuller with a mixture of deference and skepticism during his lifetime, despite his prodigious achievements. He endured rejection at the hands of the American Institute of Architects early in his career, only to be celebrated in the inaugural issue of Perspecta in 1952 as one of three "new directions" in architecture, along with Philip Johnson and Paul Rudolph. Whereupon Johnson in turn acknowledged a certain respect for Fuller even as he dismissed him as a delirious technician in "The Seven Crutches of Modern Architecture," published two years later in the same journal." (ANY, No. 17, 1997, p. 15)

6. Loretta Lorance, Fuller, R. Buckminster, International Dictionary of Architects and Architecture, Volume 1: Architects, Detroit, MI: St. James Press, 1983, pp. 281-3: 283.

7. For typical treatments of Fuller's work see Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History, 3rd ed., 1992, which discusses Fuller's work as an alternative to modernist architecture; William J.R. Curtis, Modern Architecture Since 1900, 3rd ed., 1996; and Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, 1960, which praises Fuller's use of technology. Fuller's designs, especially the Dymaxion House and the Wichita House, are usually treated as prototypes for futuristic housing as in Yesterday's Houses of Tomorrow: Innovative American Homes 1850 to 1950, H. Ward Jandl and others, 1991.

8. Fuller had no professional training in any field and described himself as an anticipatory comprehensive designer which means he was a generalist trying to use present technology to anticipate future needs. (BuckyWorks, pp. 62-65) He did receive "limited formal education" at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, MD, where he spent "a few months" in 1917. (The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, p. 13, and BuckyWorks, p.4)

9. Fuller used mathematics to justify his radial or circular design: the shortest distance between two points is a straight line. A circular configuration is preferred because in a circle there is a consistent distance, the diameter, from the center to all points on the perimeter. In a house with a radial plan all parts would be quickly and easily accessed from the center. Therefore, this configuration would help its inhabitants save time which he believed was the most important commodity of modern living. Fuller believed time was replacing gold as the economic standard: "Without legislation recognizing it, the world is now on a time standard instead of a gold standard in temporal things. Wasting time is exactly the same as throwing away gold used to be. Therefore, we are forced to design and figure in the fourth dimension which is time." (R. Buckminster Fuller, 4D Time Lock, Chicago: The Author, 1928, p. 10) There is second explanation on page 15 and a third on page 16.

10. No documentation has been found to date to verify that Fuller actually made the presentation at the 1928 AIA convention. Drafts of two texts that appear to be the speech he could have given to the AIA and a rejoinder he wrote upon his return are in Volume 33 of the Chronofile. As far as appreciating Fuller's contributions to architecture, architects, historians and critics differ widely in their evaluation of Fuller's significance. The misunderstanding of his intentions still evokes dismissal of his work. For example, in what the publishers describe as a "pioneering critical survey of the most significant European and North American statements of architectural theory," Hanno-Walter Kruft writes: "With...Fuller...we find all conventional concepts of architecture scattered to the winds. Fuller saw architecture as applied technology — an arrangement of universal laws expressed in terms of energy, mathematics, rationality...Fuller's lightweight constructions serve a function as large temporary buildings for exhibitions and similar purposes but they cannot be considered as architecture, nor should the principles behind them be considered as relevant to architecture." (A History of Architectural Theory from Vitruvius to the Present, New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1994, pp. 438-9). Curiously, Kruft seems to have included Fuller simply to discredit him. If the two references to Fuller listed in the bibliography and footnotes are his primary sources of information, it is easy to understand Kruft's misreading of him.

11. Cities Becoming 'Peas of One Pod,' p. 5.

12. Ibid., p. 5.

13. Fuller sent 4D Time Lock to an impressive list of prominent people including Henry Ford, Bruce Barton, Ralph T. Walker, Christopher Morley, and the presidents of Harvard University, M.I.T. and the University of Chicago. A complete list, with replies, is given on pages 38-54 in the 1972 edition of the book.

14. The Chronofile documents the extensive network of acquaintances in the architectural and building professions Fuller developed as President of Stockade Building System. Stockade was acquired by the Celotex Company in 1927 after Hewlett sold his shares and Fuller was forced out. (Chronofile, Vols. 27-32, 1923-1927)

15'Dymaxion' is a combination of 'dynamism,' 'maximum,' and 'ion.' Fuller claimed that the word 'dymaxion' was the result of a collaborative effort between himself and Waldo Warren, an advertising specialist. To date, no confirmation or contradiction has been found in either Fuller's or Marshall Field's archives. For an account of the process through which 'Dymaxion' was developed see The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, p. 21.

16. Marshall Field asked Fuller to display the model in the Interior Design galleries because the store was promoting furniture recently purchased in Europe. Fuller claimed that the store's intention was to make the 'advanced design' of the furniture appear conservative in relation to the design of the house. (The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, p. 21) There is a two-minute clip in the movie Buckminster Fuller: Thinking Out Loud (Simon & Goodman, 1997) that shows Fuller presenting the model. In the movie, Antonio Salemme, a sculptor, explains that Fuller made the model in six months while staying in Salemme's Greenwich Village studio and then presented it to the Architectural League. Salemme must be talking about the second model for the Dymaxion House even though the clip shows the model displayed at Marshall Field. Fuller was living in Chicago when the first model was made and did not move to New York until after April 1929. (Chronofile, Vols. 35-36, 1928-1929)

17. These included a electric stove, dishwasher, 3-minute laundry unit, and a central ventilating system that removed dust from the air and maintained an optimal temperature. For a more complete inventory see Joseph Corn and Brian Horrigan, Yesterday's Tomorrows: Past Visions of the American Future, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984, pp. 67-69.

18. This calculation is based on the fact that the first model was exhibited at the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art from May 20-25, 1929, and the second model was exhibited in the same gallery from March 12-14, 1930. (Chronofile, Vol. 35, 1929 and Vol. 37, 1930)

19. This second model is the one that is most well-known and its metallic, spaceship-like appearance is one aspect that contributed to its being classified as fantastic or futuristic. Although the use of aluminum for the frame (such as the 1931 Aluminaire House by A.L Kocher and A. Frey) or for the cladding of a building (most notably Otto Wagner's Die Zeit, 1902) was explored, the convention of an orthogonal footprint was maintained unlike Fuller's hexagonal living area suspended above the ground from the central mast. In addition, there are a number architects who have investigated the possibilities of a central mast building throughout the twentieth century including Frank Lloyd Wright (St. Marks Tower Project, 1929, and Johnson Wax Research Tower, Racine, WI, 1949), George Keck (House of Tomorrow, Michigan City, IN, 1933), Richard Neutra and Peter Pfisterer (Diatom-One-Plus-Two House Project, 1926). A second factor strongly contributing to the relegation of the Dymaxion House to the realm of futuristic housing was the inclusion of the numerous appliances and mechanical systems. This was not as fantastic as critics and historians claim. Although some of the appliances Fuller specified, especially the 3-minute laundry unit, were too complicated for production in the late 1920s, the majority of the appliances and systems Fuller included were available. (See my article Promises, Promises: Household Appliances in the 1920s, Part 3: Architecture, June 1998)

20. According to Fuller: "The new tool of this age is metal from which has been born mechanics or directed mechanical motion, which is governed fourth dimensional design. It is metal that has made possible the automobile, the railroad, the airplane, telephone, wireless, the clothes on our back and all our food, our city skyscraper. Generally, and structurally speaking, we use it in our houses in the form of nails only. Structurally the characteristic of the new tool, metal, different from any of the tools of other ages, is its fibre or tensile strength, tremendously in excess of any other tensile unit ever created." (4D Time Lock, p. 4, italics in the original)

21. This is somewhat ironic because, except for the geodesic dome, Fuller intended that his houses be taken apart, crated and shipped to the site for assembly by hand when relocated. Ideally, the geodesic dome would be flown to its new site. See note 39 below.

22. The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, p. 13.

23. Fuller claimed that his understanding of architecture and building was learned from practical experience only and primarily during his years at Stockade: "That is when I really learned the building business...And the experience made me realize that craft building — in which each house is a pilot model for a design which never has any runs — is an art which belongs in the middle ages." (The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, p. 13)

24. Fuller's knowledge of 1920s architecture and architectural theory was much more greater than he admitted. In Vol. 34 of the Chronofile is a five-page reference list for 4D Time Lock. Although it cannot be known how many of these items Fuller actually read, the fact that he included them indicates his familiarity with the architectural currents of the 1920s. These two are items number 4 and 56 on his reference list. (Chronofile, Vol. 34, 1928)

25. Wright first presented "The Art and Craft of the Machine" as a lecture in 1901. He reworked it into an essay. In The Cause of Architecture consisted of two separate series published in Architectural Record during 1927 and 1928, respectively. Wright continued the argument of The Art and Craft of the Machine in the 1927 series in which he discussed the pros and cons of the use of the machine, or, as he described it, "the architect's tool." In the 1928 series, Wright was more concerned with design. In both he argued against allowing standardization to destroy the art of building.

26. Frank Lloyd Wright, In the Cause of Architecture: What "Styles" Mean to the Architect, The Architectural Record (Vol. 63, No. 2) February 1928, pp. 145-151: 146. This idea is expressed in Wright's textile block houses from the first half of the 1920s, as seen in the 1923 house, La Miniatura, he designed for Alice Millard. Wright used pre-fabricated and mass-produced components but in a traditional manner: different elements were brought together to produce a unified and aesthetic building.

27. 4D Time Lock, p. 79. It is not clear to what Fuller is referring when he describes Corbusier's "telegraphic style of notion." It may be that he thought Corbusier was clear and concise.

28. Chronofile, Vol. 30, 1927-28. Fuller Houses was the original name of the 4D/Dymaxion House project. Fuller reused "Fuller Houses" for the company he created in 1945 to manufacture his post-World War II housing design.

29. There is no documentation in the Chronofile for the beginning of the Fuller Houses project. It is first mentioned on November 22, 1927 in the diary by Fuller's wife, Anne, who noted that Fuller talked about 'Fuller Houses' with a salesman from Stockade. (Vol. 30, 1927-28) Therefore, how much influence Towards a New Architecture might have exerted on Fuller is unknown

30. Only the most significant similarities will be discussed in this essay. For Le Corbusier, the page numbers in the following notes are from: Towards A New Architecture, New York: Dover Publications, 1986.

31. Fuller claimed that "The new Ford cost approximately $43,000,000 for its first single unit, but on a basis of an infinity of reproductions, each of the latter cost but $500...Price varies with models and sizes." Therefore, Fuller believed, mass-production would serve to lower the cost of housing in the same manner: "It was inevitable...that a complete house with every requirement, industrially to be fashioned, should eventually be evolved...Tho [sic] it cost 100 million if but one unit were constructed, the machinery, thereto attendant, and distribution system having been set up, replicas may be had for close to the material cost, or on a weight basis as all shipping or machinery is sold." (Buckminster Fuller, "Tree-Like Style of Dwelling Is Planned," The Chicago Evening Post Magazine of the Art World, December 18, 1928, p. 5) Le Corbusier briefly mentioned this under the heading of A question of a new spirit. (Towards A New Architecture, p. 264)

32. Towards A New Architecture, pp. 242-43.

33. Towards A New Architecture, pp. 247-48. See note 13 for a brief discussion of Fuller's interest in servants and housekeeping.

34. Corbusier introduced this phrase in Towards A New Architecture, see p. 4. Although truncating Corbusier's phrase would have been a typical word game for Fuller, "machine for living" is thought to have first been associated with Fuller in the article "Buckminster Fuller: The Dymaxion Architect," Time, Vol. 83, No. 2, January 10, 1964, p. 48. Amusingly, the article refers to Corbusier's axiom "machine for living in" (machine à habiter) as "machine-for-living." Ed Applewhite, who compiled a the four volume Synergetics Dictionary, a catalogue of Fuller's words and sayings, believes "machine for living" was first used relationship to Fuller's work in The Dymaxion Architect.

35. Reyner Banham, Theory and Design in the First Machine Age, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 1989, p. 326.

36. As with Fuller and the Dymaxion House, the maturation of the ideas Corbusier expressed in the Villa Savoye resulted from a long period of development. The Villa Savoye is considered to be the culmination of ideas which were initiated with Corbusier's 1919-1920 project for the Citrohan House. For a history of this development see Tim Benton, Villa Savoye and the Architects' Practice, in H. Allen Brooks, ed., Le Corbusier: The Garland Essays, New York: Garland, 1987, pp. 83-105 and Tim Benton, The Villas of Le Corbusier, 1920-1930, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987.

37. Fuller addresses the issue of mobility in 4D Time Lock on page 63 as part of The 4D Letters Patent where he writes: "In a dwelling intended for quick and easy and erection and subsequent moving from place to place with relatively great facility, the weight of the structure itself becomes a significant item." A lengthy discussion of mobility is provided in the reproduction of his August 31, 1928 letter to George Buffington. The excerpts relevant to the issue of mobility are as follows:

"[...]4D mobile, lightful, 20th century tower housing[...]is a subject of common progressive, harmonic, and creative interest[...]4D tower housing represents spirit of freedom that is synonymous with American[...]time is new currency, new base of economy[...]owning property is feudalistic[...]Economics are dependent upon free mobile individualism which is the antithesis of static properties[...]With the establishment of the new mobile housing industry, will the other industries of automobile, airplane, radio, furnishings, etc., no matter how complimentary to the main housing, assume the proportions of the motor launches, airplanes, and myriad other gear, to the main battleship, being but accessories of convenience." (pp. 120-132)

38. The Dymaxion World of Buckminster Fuller, p. 13.

39. Ibid., pp. 17-18. In the 1950s, Fuller's ideal of transporting houses by air was realized when geodesic domes were transported by helicopters. Fuller was enamored by the technology of the airplane and the potential he saw in using the sky as a second "ocean." According to Fuller, the sky ocean, unlike the water ocean, completely surrounds the Earth and provides direct access to all points on it. In terms of using the airplane as a means of transporting assembled buildings, there are limitations placed upon the size and weight of the structures. Of course, reducing the weight of buildings was one of Fuller's design criteria. And, ground transportation systems do impose limitations upon the design of mass-produced housing. For example, Allan Wallis argued that the width of trailers was restricted by the width of highway lanes in Wheel Estate: The Rise and Decline of Mobile Homes, New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

40. Mies van der Rohe, "Industrielles Bauen", G, no. 3, June 10, 1924: 8. This quote was taken from the translation in Philip C. Johnson, Mies van der Rohe. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1947.

41. For a brief history of the magazine and Mies's relationship to it, see Franz Schulze, Mies van der Rohe: A Critical Biography, Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1987, pp. 105-108. Fuller did study German while a student at Harvard in 1913, but, received a "D" in the class. (Harvard University Archives, Richard Buckminster Fuller Student Record Card) Whether or not he was proficient enough in German to read Mies's article in the original remains unknown.

42. 4D Time Lock, p. 8.

© 2001 PART and Loretta Lorance. All Rights Reserved.