| |

The first decades of the twentieth century saw the

pace of business, industry, and society accelerate with the introduction

of new technology. The adding machine, motorized factory equipment,

the assembly line, and the automobile--all of these inventions urged

people to pick up the pace of daily life and work. Even the home,

the "haven in a heartless world," was not a shelter from

time-saving technology. Middle-class homemakers eagerly followed

the twentieth-century trend and modernized their homes, but soon

realized that they had to learn to adapt their daily routines to

the unforeseen changes that new technology brought.

With the introduction of gas- and electric-powered

appliances such as ranges, refrigerators, vacuum cleaners, and washing

machines, the modern woman's workday necessarily changed. Like contemporary

workers in modernized factories, homemakers were under pressure

to speed up their work and do more than before. They sought advice

on how to make the transition to the world of modern homemaking.

But, homemakers were not the first to seek advice.

The profession of the efficiency expert, or scientific manager,

arose at the turn of the century specifically to address the problems

that new technology presented to industrial labor and the corporate

world. These experts were, for the most part, self-employed consultants,

who were hired by businesses to improve efficiency in their factories

and, sometimes, their offices. The most famous efficiency expert

was Frederick Winslow Taylor, whose hallmark scientific management

techniques showed how a worker on an assembly line might work more

quickly. The technique was to watch the motions of the worker. Did

he or she need to walk a distance to pick up a part from another

workstation? Or, was the worker standing in the wrong place in relation

to the machinery and consequently having a difficult time seeing

what was being done? For Taylor, finding the optimum arrangement

of worker and machine would keep the process of work going smoothly,

thus maximizing the output of the worker and factory. This was good

for the company's bottom line.

Frederick Taylor had several consultants working

for him. One of them was Frank Gilbreth. Gilbreth came up with a

few ideas of his own and broke away from Taylor. Then, with his

wife Lillian (Fig. 1), he set up an independent consulting business,

Gilbreth Inc. In the years of their marriage, from 1904 to 1924,

Frank and Lillian Gilbreth were efficiency consultants to business

and industry. Like Taylor, they were interested in speed, but they

added an element to the practice of efficiency: reducing fatigue.

They believed that fatigue slowed a worker down.

In the years of their marriage and business partnership,

the Gilbreths were hired by many organizations, from the United

States Army to the American Heart Association. All wanted advice

on how to maximize efficiency and reduce fatigue in a variety of

work situations.

Industrial work had been a lucrative source of income

for the Gilbreths. Companies that hired them were willing to invest

in consultants in order to increase efficiency and boost profits.

But the Gilbreths were believers that their ideas of efficient work

were for everyone, not just big business. Their goals and beliefs

were very fitting for the Progressive Era, of which they were firmly

a part. They practiced what they preached. They worked out of their

home in Montclair, New Jersey and used their household as a laboratory

of sorts. Anyone who knows the popular story entitled "Cheaper

by the Dozen" will know that the Gilbreths believed efficiency

should start at home! The story, which was made into a movie, was

written by the Gilbreth children and told how every household activity

became a study in saving time and energy, from taking a bath to

packing suitcases for vacation.

When Frank Gilbreth died suddenly in 1924, Lillian

Gilbreth faced a desperate situation. The couple had eleven children,

ten of whom were living at home. Because of their large family and

because they constantly put money back into the business, Lillian

could not retire upon Frank's death. She decided to forge ahead

with the efficiency business. She continued to seek clients in industry,

but also employed her scientific management expertise in a more

freelance way by writing advice manuals for women about household

work.

|

|

|

Lillian had a wealth of experience and case studies

in household efficiency. A businesswoman, a trained industrial engineer,

and a Ph.D. in management psychology, she had an unusual but handy

combination of skills and experience. While she was not a member

of the home economics profession per se, she ventured into that

territory with the publication of her first household advice manual,

The Home-Maker and Her Job in 1927. She wrote her book for

middle-class homemakers of the 1920s who faced the dual realities

of having no hired household help but a heap of new labor-saving

appliances. In The Home-Maker and Her Job, Gilbreth sought

to inspire homemakers to think of their homes also as workplaces

and to plan their space and their time accordingly. Essentially,

she urged them to employ some of the same measures that the Gilbreths

had implemented in their factory consulting work.

When the Gilbreths did work for industry, their

results were easy to measure. A company would ask them to figure

out how to produce more widgets per hour. Or, to design a work station

that would eliminate leg or back strain. The result could be seen

in greater factory output or fewer complaints of fatigue and fewer

breaks or even sick-days.

It could not be debated that homemakers did

work all day, but did they view their homes as actual workplaces?

The question may not be how a homemaker could bake more pies per

hour. Rather, could she finish her chores earlier in order to have

more time to read to her daughter? Or, could she use time-saving

appliances more efficiently to make fewer trips up and down the

stairs? Were these workplaces inefficient? Did the new appliances

help or hinder the work process? Was the work day unplanned? In

essence, did chaos reign? If so, then the homemaker would likely

feel stressed, fatigued, and out of control. What Gilbreth emphasized

in The Home-Maker and Her Job was the goal of "happiness

minutes"--moments when everything would come together and there

would be a sense of peace and accomplishment.

In the home, on the other hand, the results could

not be measured in the same way. Gilbreth summed up the goal of

efficiency in the home as more "happiness minutes." This

would have seemed silly to an industrialist, but Gilbreth could

see no better way to measure the overall result of having a more

efficient home. Happiness minutes occur when the homemaker is rested.

When the household paperwork is organized and the bills paid on

time. When meals are planned and not stressfully thrown together

at the last minute. New time-saving appliances gave homemakers more

freedom--the freedom to take on more jobs, to make cooking more

complex, to make the house cleaner, but at a resulting price of

having too much to do and fewer minutes of happiness.

Stepping back from the situation, one might point

out the obvious solution: just do less. Let the dust build up for

a few more days. Open a can of soup for dinner. Let all those expensive

modern appliances do the work. But, Gilbreth or any woman picking

up a household advice manual would recognize the note of surrender

in these solutions. Their assumption was that mom could and should

be able to do it all. And, they looked for the answer to the mystery

of why those new gadgets did not make the homemaker's day effortless.

Historians have been searching for the answer, too.

When electricity and gas were introduced into homes in the early

twentieth century, they replaced elbow grease as the main power

behind many household jobs. Yet, the appliances frequently meant

that effort was expended elsewhere. For example, the cooking range

replaced the wood or coal stove. This wonderful appliance eliminated

the need to fetch fuel and refill the power source. It also made

climate control in the kitchen a distinct possibility. However,

with an unbearably hot kitchen with coal or wood burning in the

stove, as was the old way, a homemaker might take some work outside--shelling

peas, sorting beans, peeling potatoes--while sitting in a chair

on the porch or in the yard to get some cool air. Importantly, she

would be off her feet for a while and getting a job done at the

same time. With climate control, it seemed more efficient just to

stand at the sink in the kitchen and get the job finished. Ranges

that allowed varying temperatures on various burners also allowed

for cooking more complicated meals. Stew and soup were fine sometimes,

but fancier dishes with individual components--separately cooked

meats, vegetables, and of course desserts--became the standard in

modern cooking. This meant more time in the kitchen, more

preparation time, more standing at the range or countertop,

not less. The vacuum cleaner was another thrilling invention that

replaced the need to take out rugs and beat them. Of course, rugs

were very infrequently taken out, as this was a time-consuming and

difficult job. However, vacuuming could be done frequently, even

daily. The vacuum was a very handy invention, but one also had to

carve out time to complete this new household task. Technology in

the home was, as it still is, a double-edged sword, cutting work

time in some cases, while adding chores and strain in others.

Assessing the homemaker's situation, Gilbreth's

advice was based on the primary belief that fatigue is what prevents

people from working to their full potential. Disorder and the stress

resulting from it, Gilbreth said, was the primary cause of fatigue,

both mental and physical. It came primarily from two sources: a

cluttered, disorganized home and a lack of a plan for activity.

A new technology like an electric egg beater could be more fatiguing

to use than a wire whisk if it was stored in the back of a cabinet

and was hard to dig out and put away, or if it needed to be cleaned

meticulously before and after every use. Too many appliances, cluttering

a countertop, Gilbreth explained, would become counterproductive

if they took away a workspace needed for chopping or mixing or if

they just made it difficult to find things. Gilbreth suggested that

all appliances may not be necessary. There was, she believed, such

a thing as giving in to all the sales pitches out there too easily.

If one bought and deemed an appliance worth keeping, only the ones

that were used almost daily should be out in plain sight and reach.

A homemaker's daily and weekly plan for work was

also turned on its side by the industrial age. Beforehand, Mondays

were washdays, Tuesdays for ironing, and so forth because these

were all-day activities before the washing machine. Now, the convenience

of a labor-saving appliance meant that any day, any time, could

be wash-day. Wash might be done more frequently than once a week.

Mondays need no longer be set aside, so new activities could creep

into the schedule. With the advent of the automobile, women also

could dash out of the home on errands. This was convenient, but

also made it harder to stick to a plan. So many possibilities, so

many things to do. This was mentally as well as physically fatiguing.

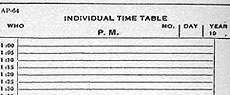

To regain control, Gilbreth suggested that homemakers

chart their daily, weekly, and even yearly activities and those

of all members of their households. The family calendar, perhaps

a staple of most households today, was a new idea in the 1920s,

and was borrowed from industry, for which the Gilbreths set up schedule-keeping

systems to keep track of deliveries, payments, contract obligations,

and the like. In the home, Mother's, Father's, and each child's

activities were to be noted so that Mother may be aware of everyone's

activities and appointments because everyone's needs and activities

affect the daily plan for the homemaker.

Difficult though it might be at first, Gilbreth

said, the homemaker too must make daily, weekly, even yearly work

schedules for herself. The homemaker had the advantage of being

worker and manager. As such she could manage her time the way she

saw fit, but it must be managed, or chaos and stress would result.

Chaos and stress led inevitably to fatigue. Fatigue made happiness

minutes impossible. A schedule would mean freedom from stress, rather

than slavery to a deadline. Gilbreth instructed the homemaker to

make a chart, like a page from an appointment book, and note everything

she must do and at what time--rise and dress, cook, make beds, do

laundry, all the way down to putting the children to sleep at night.

The homemaker seeking happiness minutes would plan wisely--plan

to do the heaviest jobs when she knew she would have the most energy.

Unlike on the assembly line, in the household, there ought to be

a buffer of time between jobs. Gilbreth wrote, "Most schedules

have been discarded because their makers forced more things into

them than they could be reasonably expected to contain." If

the schedule did not work, either a homemaker was not allowing enough

time to complete each task, or there were too many interruptions.

A major culprit was the telephone. Gilbreth advised women to "disconnect

the telephone." The telephone, she understood, was a technology

to add to the vacuum, the egg-beater, and so forth that was a welcome

addition to the household. It could be valuable as a time-saving

device to relay a message. However, it could also be a terrible

time-waster. Again, the homemaker had to eye this technology with

suspicion and be aware of its double-edged qualities.

While chaos could be controlled and considerable

mental and physical fatigue alleviated with a workable schedule,

Gilbreth cautioned that boredom with tasks could similarly frustrate

efficiency. Boredom could breed resentment, leading to mental fatigue.

Once a schedule was in place, breaking it was fine once in a while,

she explained, for the mental exercise and the fresh outlook on

things it would bring. Or, quite simply, "for the fun of breaking

the schedule." Once again, as manager and worker, the homemaker

had the freedom to do this. Gilbreth wrote: "...efficiency

is doing the thing in the best way to get the desired results. And

these [results], we must never forget, are the largest number of

happiness minutes for the largest amount of people."

When Gilbreth's book appeared, there was no shortage

of advice for homemakers. The Ladies' Home Journal and Good Housekeeping

offered wisdom and tips every month. Cookbooks crowded the shelves,

exclaiming all of the fabulous dishes that could be prepared with

modern cooking equipment. Magazines with ads for shiny new appliances

promised happiness through more exciting menus. Yet, all of these

fell short of what they promised. Owning more complex equipment

or making a job last longer were taking the happiness out of a homemaker's

day.

Gilbreth's book stood out because it went to the

heart of the homemaker's situation: that modernization was making

things more difficult. Through her explanation of fatigue and scheduling,

Gilbreth showed homemakers why this was the case and urged them

to reexamine the way they did work. With only possibilities but

no plan, a homemaker could never feel as if she was getting her

job done. But, when she knew her tools and how to use them, when

she had a schedule and completed it, a homemaker could feel accomplished

in her job. That sense of peace and satisfaction would help her

be a more accessible wife and mother and a happier woman--if only

for a few minutes at a time.

Sources>>

Author's Bio>>

|

|