|

Modern American Fashion Design American Indian Style |

by Mary Donahue

|

|

Fig 1: M.D.C. Crawford, “Museum

Documents and Modern Costumes,” The American Museum Journal

18, no.4 1918.

|

The idea of an “American” design gained momentum in segments

of the business, museum and design world during the 1910s and 1920s.1

Self-conscious interest in the design arts as independent of outside influences

is traceable to the origins of the United States as a nation at the expense

of England.2 This feeling intensified hand in hand with industrial

expansion, a pace that quickened in the early twentieth century. With

shortages in European design models brought about by World War I, the

need to rely more upon local resources for inspiration, materials and

manufacturing - to take nothing away from genuine national sentiment -

forced the question of identity. Museums were important in this context.3

From the east coast to the mid west in Chicago, Cincinnati, Newark, New

York City and Philadelphia, museums actively promoted their holdings as

springboards for American design, strengthening bonds or forging new ones

with the business community, which took advantage of policies that opened

up collections through study rooms, exhibitions and educational programs.

Since revolutionary colonists wore homespun, design as American has been

intertwined with women’s clothing.4 The early twentieth-century

quest for a national design was replicated in fashion as ties with Paris,

which held dominance, eroded due to the war. Similarly intent on defining

something American, leaders in the feminine apparel industry in New York

and New Jersey focused on New York museums for the designing of garments,

trim, fabrics and accessories. Today the view about an emerging American

fashion centers on the styles of New York manufacturers and designers,

but a fundamental achievement was to generate and carry out an idea about

a national style, a development more widespread than New York. The use

of American Indian collections has a history of its own worth studying

for what it reveals about the nature of American fashion as well as national

identity, during a time when Euro-Americans increasingly identified with

indigenous peoples as true Americans.

Conceptualizing American Fashion

An American fashion was defined from the combined perspective of the business

and museum world in the main articulated by M.D.C. Crawford, who bridged

both domains. Crawford was a design and research editor for the garment

industry’s influential trade paper, Women’s Wear, and a research

associate in textiles at the American Museum of Natural History in which

capacities he established an alliance between the museum and the garment

and textile trades.5 By 1917 he had orchestrated the founding

of study rooms, lectures and workshops at the museum to the enthusiasm

of leading manufacturers and designers, among them from the garment business

were Max Meyer of A. Beller & Co., Jessie Franklin Turner of Bonwit

Teller, Edward L. Mayer, J. Rapoport, Mary Walls of John Wanamaker's and

E. J. Wile; and from the cotton and silk industry were Belding Brothers,

Cheney Silk, H. R. Mallinson and Johnson, Cowden & Company.

Crawford worked in close partnership with Stewart Culin, curator of “ethnography”

at the Brooklyn Museum.6 Under Culin’s leadership the

museum opened a study room in 1918 and initiated outreach and programming

for the design community, especially in clothing and textiles. For his

part Richard Bach at the Metropolitan Museum of Art embraced the wide

scope of design.7 Rather, Crawford and Culin set the pace in

Americanizing fashion.

Through his writing Crawford became an important spokesperson for the

fashion and museum world, positing ideas mostly in connection with his

institution and its nonwestern holdings, but which mirrored the thinking

of museums around the country with their various strands of western and

nonwestern objects. This makes clear that fashion gained an American identity

by originating in the United States in terms of concept, materials and

manufacture. Crawford reveals the intent to create a modern American fashion

through an international collection that embraced Africa, the Americas,

Asia, the middle East, Europe and the Pacific islands. In a 1917 article

in the journal of the American Museum of Natural History, he describes

how ready-to-wear and silk and cotton manufacturers looked to the museum

for direction, stating that the “Primitive” American art collection

and the art of China, the Philippines and South Sea Islands would “...serve

as a basis for our own distinctive decorative arts.”8

A 1918 article in the same journal entitled “Museum Documents and

Modern Costume” explains that:

Instead of the usual method of importing modern foreign costumes [themselves based, generally, on foreign museum collections], our designers, familiar with the practical needs of today, have gone direct to original documents for their inspiration. The work, therefore, marks one of the most important movements in the development of a truly American type of industrial art…9

The reference to “industrial art” and “modern costume”

indicates key aspects in the contemporary understanding of American fashion.

The first is advanced technology. The national identity was entwined with

the machine. To be an American design was to be produced in American factories

with American manufactured materials. Technology was in turn equated with

the modern. Although popularly speaking the term “modern” also

meant contemporary, the machine represented up-to-date manufacturing methods,

and designs intended for industrial production were modern for this reason.

The fact is that handicrafts retained importance, but the emphasis was

on design for manufacture.10 It is not coincidental that most

garment and textile producers and designers interacting with the American

Museum of Natural History and the Brooklyn Museum were engaged in quantity

production.

It is tempting to apply to design the tendency of 1910s and 1920s American

artists to borrow from Native American and African forms in pursuit of

modern solutions to aesthetic problems - read abstraction.11

Although individual designers and manufacturers may have been caught up

in being modern, it would be misleading to apply the same agenda to design.

Fueled by economic motives, the first objective of design is commerce

and thus very different from the undertaking of artists. Taken together

the proximity of “ethnographic” collections and the nurturing

environment provided by Culin and Crawford cultivated an interest in art

outside of western traditions. But this was offset by the utilization

of European art at both the Brooklyn Museum and Metropolitan Museum of

Art.

What use there was of nonwestern art in modern terms pertained largely

to the market appeal of up-to-date styles. This is clear in fashion discourse

that alludes to abstraction. “Blouses of Modern American construction.

In the popular blouses of today, emphasis is laid on harmonious colors

and on designs that have been refined to the point of simplicity,”

highlighted designs recalling Northwest Coast traditions.12

American Fashion Indian Style

The impact of Native American art on fashion is discernible in drawings

and garments that survive in illustrations in Crawford’s articles,

especially in Women’s Wear, and installation photographs from museums,

galleries and department stores along with the evidence of exhibition

catalogs and the fashion press.13 Even a sampling provides

a sense of how American Indian traditions were incorporated. A starting

point is Crawford’s 1918 article mentioned above. It examines the

results of a three-year campaign conducted by Women’s Wear in league

with the American Museum of Natural History in order to improve textile

and garment design.14 Representing “…the first fruits

of what I may term `creative research’ by the American costume industry,”

the article contains four designs associated with Native American traditions,

namely a silk fabric inspired by pottery from the “American Southwest”

(Edward L. Mayer); a sport coat with embroidery based on “primitive”

basketry (A. Beller) (Figure 1); and under the caption “Designs suggested

by Indian Documents” :

At the left a dinner gown, or negligee, embroidered in wool. The method of connecting the ends of the belt was suggested by girdles from the Goajiro Indians in the museum’s collections from northern Columbia, and the decoration was inspired by a study of North American Indian collections (Bonwit Teller).

At the right. A black satin evening gown with silken and bead tassels. The idea of the tassels owes its origin to the buckskin thongs that hang from a Dakota Indian costume (Edward L. Mayer).

A milestone in this history involves thirtyfour displays of dress and

accessories shown in the "Exhibition of Industrial Art in Textiles

and Costumes" at The American Museum of Natural History in November,

1919. The catalog together with an article in the Museum Journal entitled,

“Creating a National Art”, written by Herbert J. Spinden, Assistant

Curator, Department of Anthropology, indicates the goal of achieving a

modern American design through the global collections housed in the museum.15

Held in the “North American Indian Hall”, the exhibition included

gowns in style and trim inspired by designs from Guatemala by J. Wise

& Co., and from the Plains by Harry Collins (Figures 2). Two blouses

by B.C. Faulkner suggest the patterns and styles associated with the Northwest

Coast and Plains Indians shirts. David Aaron & Co., a manufacturer

of embroidery, drew on a variety of sources such as Pueblan in an effort

to demonstrate the use of art from around the globe “in modern machine-made

embroidery” (Figure 3). Similarly The American Bead Company borrowed

from Woodlands traditions in order to produce “Modern uses of Beads

in Dress Accessories”.

|

|

Fig 3: The Brooklyn Standard

Union, November 10, 1919.

|

Overall the Native American influence derives from baskets, pottery and textiles associated with the northern hemisphere (Northwest Coast, Southwest and Woodlands cultures). As for garments shirts prove to be the most significant in keeping with designs from both continents. From these, color, patterns, motifs and materials were adapted in the designing of trim and ornamentation for staples like dresses, suits, coats, blouses and lingerie, and for dress fabrics and accessories. There is a constant dialogue with the prevailing Parisian line, but also departures that would be more extensive if more were extant. It is surprising how closely the dresses by Harry Collins resemble the original Plains Indian garment (Figure 4). Crawford’s 1918 article describes something similar in an “...automobile wrap in pongee silk, practically an exact copy of a Korean grass linen garment."16 A 1926 article in the bulletin of The Metropolitan Museum of Art states:

Thus we know of the costume designer who spent her time at the Museum seated alone in a gallery of Near Eastern art. She made no notes, she went to no other galleries, she simply ‘exposed’ herself to the influence of graceful line and gentle color, knowing her own receptivity to such effects. The result was a whole series of models recalling in form nothing she had seen at the Museum, yet subtly registering in color key and in certain treatments of line the effect of the ‘exposure.’17

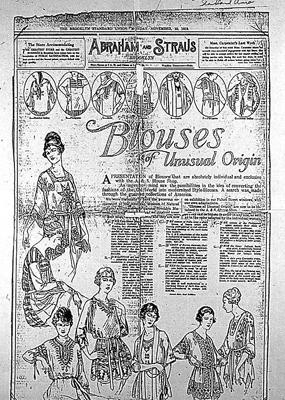

The fashion press reveals that the museum’s impact on blouses was

not limited to the designing of trim and ornamentation, but dictated the

line of silhouettes, hems, necks and sleeves. Because it was then crucial

to a woman’s wardrobe, the history of the blouse is doubly important

in the Americanization of fashion. In fall, 1919 Women’s Wear galleries

showcased “blouses” from around the world donated by the American

Museum of Natural History and the Brooklyn Museum in which Native American

examples were prominent.18 The exhibition generated a lot of

attention in the trade. Within weeks Women’s Wear depicted garments

that grew out of it, including a blouse “fashioned after a garment

of the Plains Indians made of elk skin and brilliantly trimmed with quill

work.”19 The excitement sparked a buyer and designer for

Abraham and Strauss department store in Brooklyn to develop a line of

blouses, which were advertised in local newspapers and prominently mounted

in a window along with the originals: one depended on the culture of the

Plains and another on the Huichol Indians of Northern Mexico.20

These adaptations show how closely the original garments were followed

(Figure 5).

In the end it is easy to call the search for an American fashion a success

from the standpoint of the New York museum group in the terms it set for

itself, at least partially. The intention was to utilize the country’s

potential in materials, manufacturing and design for which an abundance

of evidence survives in the fashion and museum press. In retrospect the

adoption of nonwestern art was not new in fashion, but traceable to France

prior to the war.21 However, as developed in New York beginning

in 1917, this tendency was rooted in this country with a mindset directed

toward local museums and based at times on indigenous sources.

Research needs to be done in order to determine how other garment areas

such as Cleveland and Chicago responded to the institutional support of

museums and to New York as a style center. As of now costume historians

who judge the Americanness of the 1910s and 1920s focus on style and a

handful of figures in the thriving garment center of New York City.22

Histories are waiting to be told elsewhere that promise to yield a variety

in American fashion under the direction of museums. The Sears catalog,

for example, sold blouses reminiscent of Plains Indians shirts and bathrobes

inspired by Pueblan textiles to women across the country from 1918 through

the 1920s.23

Unfortunately the very nature of utilizing museum collections carries with it the danger of designing costume, a fault of some of the era’s better fashions.24 The recycling of history, a commonplace of fashion, walks a narrow line between the poles of “dress up” and “dressed up” and perhaps it is for the best that these American fashions incline more toward fabric, trim and color than overall design in the elaboration of styles from the past.

Dressing Up Indian

What strikes me about the fashionable wearing of Native American styles

is the concurrent practice of dressing up as Indians in order to cultivate

an American womanhood. In Playing Indian Philip J. Deloria maps a history

of Euro-American men donning feathers, blankets and face paint in activities

hinged upon finding a national self.25 While persisting from

colonists who threw tea into Boston harbor, to nineteenth-century aspiring

national poets and Woodcraft Indians to the men’s movement, more

recently, it wasn’t until the early 20th century that playing Indian

became solidly entrenched among women and when it did it was in terms

of the Campfire Girls. Stemming from the late 19th century this organization

took hold in the 1910s, borrowing from Ernest Thompson Seton’s Woodcraft

Indians, which stressed Indianness as a key part of American manhood.

With values rooted in nature and physical work Seton sought to bolster

masculinity in city boys feminized by industrialization. Campfire Girls,

under the guidance of Luther and Charlotte Gulick, aimed at shaping ideals

of American femininity in linkage with Native American women and their

tie with nature, motherhood and domesticity. As a way to emphasize this

affinity, the membership made and wore clothes in imitation of their models.

Deloria puts the incorporation of women into the tradition of playing

Indian into a larger picture entwined with national identity in line with

“…modernity, which has used Indian play to encounter the authentic

amidst the anxiety of urban industrial and postindustrial life.”26

Although recognized as American and invoked to prove the existence of a national style, self definition through American Indians did not belong in the main to the fashion world’s program. Things Native American were not singled out in the museum collections and thus cannot be counted as part of an identity quest via indigenous peoples. The latter then preoccupied many white Americans, especially after the war, coupled with a novel appreciation for American Indian culture, which is where fashion enters the picture.27 Even though in general the fashion discourse is stereotypical and ethnocentric, it expresses genuine interest in the aesthetic value contained in Native American cultural forms, and recognizes therein art rather than ethnography in step with the new thinking. Just compare “Primitive American art collection” and “Made in slate gray Georgette crepe, the wide bands incorporate all the exquisite color sense of men who looked to Nature for all their colorings.”

Rather than an antidote to industrial angst, the adoption of Native American forms can be linked to a celebration of machine technology and to the related question of Americanness, a situation addressed in 1919 by Crawford:

The exhibit in the Mallinson booth is in every detail essentially American. The silks have been woven and printed in the eight Mallinson mills in America, the designs have been created right here in America, and in many instances were inspired by American sources. In practically all instances, the designers, themselves American, have studied, dreamed and originated in American atmosphere.28

The stress on technology and Americanness in design in general is understandable

as a way to offset the economic crisis brought about by the war and to

bolster industry, which had a positive influence in advancing the profession

of designer, even as it outdistanced handicrafts and created problems

for labor.29 The striving in fashion to make something distinctly

American produced in number offered a needed alternative to the stratified

world that the Parisian couture represented, despite the fact that differences

in cost and status remained. But the mark was missed in not paying more

attention to the conditions of the users and not following through to

the fullest, when in the mid 1920s eyes turned again toward Paris.

What about the women outside of the Campfire Girls who knowingly wore

fashionable items indebted to Native American culture? Is this an attempt

to identify with Indians as Americans, a phase in the construction of

American femininity, a stance against Paris, or a fashion expression?

Are the four mutually exclusive? I will follow the lead of Deloria in

recognizing a paradoxical relationship concerning national identity, American

Indians and fashion design to end with the mental image of white girls

at play dressed up like “Indian braves”.30