Robert

Smithson: Language to be Looked At and/or Things to be Read, Drawings from

1962-63

by Robin Clark

"Robert Smithson: Language to be Looked at and/or

Things to be Read, Drawings from 1962-63"

James Cohan Gallery

February 5 - March 4, 2000

A spate of exhibitions featuring sculptors' drawings demonstrates the fluidity with which artists worked across media during the 1960s and 1970s. Recent group and monographic shows highlighting works on paper by Gordon Matta-Clark, Eva Hesse, Sol Lewitt, Nancy Holt and Robert Smithson attest to both the richness of this material and the current appetite for it.1 No one in this community of artists exploited the permeable boundaries between two and three dimensions, or dialectical relationships between words, images and objects, as thoroughly as Robert Smithson.

|

For this reason it is fortunate that "Robert Smithson: Language to be Looked at and/or Things to be Red, Drawings from 1962-63," held this spring at James Cohan Gallery, focused on Smithson's early works on paper. It served as an important complement to the shows mentioned above, some of which dealt with Smithson's better-known work in minimal and process-oriented idioms from the later 1960s. The Cohan Gallery show reopens provocative questions posed in the last decade by scholars including Caroline Jones and Eugenie Tsai. How should we read Smithson's text-emblazoned drawings and collages from the early 1960s? And what relationship might this work (which was later rejected by Smithson and critics alike as juvenilia) have to his tremendously influential production during the later 1960s and early 1970s? 2

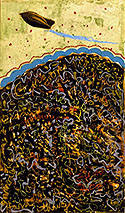

A majority of the works displayed in the Cohan Gallery show are free hand ink drawings that foreground an interplay between text and cartoon-like images. The simultaneously hieroglyphic, pictographic, and phonetic possibilities of words as material are explored in works such as No Vacancy, 1962. The title phrase of this drawing is rendered in an overwrought schoolboy script, while the tawdry pleasures imagined within are described by the word "VASELINE" exclaimed 52 times on the top third of the sheet. Compulsive repetition as ritual and ornament play out in a grid of 11 x 26 5-pointed stars, and in the form of an expressionless female nude, outlined by the text "butter on velvet," repeated five times below. Smithson's proclivity for marrying banal and apocalyptic themes during this period is demonstrated by the incantation "Price War Last Day" inscribed like a doomsday pediment across the bottom of the page.

|

Of the 31 works on paper included in the exhibition, six of the densest and most complex pieces are collages. Tension between center and periphery, a dynamic later developed more rigorously in Smithson's theory of site and nonsite, is humorously explored in St. John in the Desert, c. 1961-63. At multiple removes from its source, the central image is a cut-out mechanical reproduction of an etching after Raphael, representing a scantily clad boy in leopard skin. This winsome St. John is surrounded by diagrams of cathode resistors, audio output recorders, and various types of circuits apparently clipped from a user's manual. The text in these diagrams is rife with organic/mechanical metaphor -- "good fuse, bad fuse" -- and advice of dubious value to St. John -- "how we put a magnetic field on tape." Technical drawings engulf Raphael's mage like improbable marginalia; clearly neither can explain the other, yet in their absurdity both the saint and the gadgets are presented as objects of desire.

The exhibition title, "Language to be Looked at and/or Things to be Read," was lifted from a Dwan Gallery press release drafted by Smithson (under the pseudonym Eton Corrasable) in 1967. The drawing that accompanied that press release (A Heap of Language, 1966) was not included in the Cohan Gallery show, but Smithson's published work from that period was represented by the inclusion of two magazine articles displayed in a vitrine.3 Both of these works, as examples of Smithson's polemic ruminations on art and history, reward sustained attention beyond the

|

© 2000 Part and Robin Clark. All Rights Reserved.