The

New Greek Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

by Dana Pilson

"This is not just a spiffing up of the galleries, this is a way of rethinking the entire Greek heritage."

Philippe de Montebello, Director of The Metropolitan Museum of Art (http://www.metmuseum.org), on the New Greek Galleries.

|

Like the renovation of Grand Central Terminal, the overhaul of the Greek Galleries (completed in April 1999) at The Metropolitan Museum of Art has revealed an astounding Beaux-Arts space. While the grand barrel-vaulted ceilings of the central sculpture hall are not adorned with celestial constellations as at the train station, the skylights allow immense shafts of sunlight through to the galleries, allowing the marble sculptures to glitter and glow. The superb renovation complements the Museum's noted collection of antiquities, which grew phenomenally from 1905 until about 1917, when a team comprised of Edward Perry Warren, a wealthy American collector, John Marshall, Warren's buying agent, and Edward Robinson, assistant director of the Museum, commandeered a steady influx of ancient artifacts, including world-class bronzes, marbles, pottery, engraved gems, and terracottas. From 1912 to 1917, the architectural firm McKim, Mead and White created the original galleries for the collection, which today includes more than 35,000 objects. Together with the Robert and Renée Belfer Court (opened in June 1996) these new galleries represent the first two phases of a three part campaign. The final phase of the master plan includes remodeling what is presently a restaurant and public cafeteria into a Roman atrium for sculpture and transforming executive offices into galleries for Roman and Etruscan art and a study collection area, thus completing the sweep of history presented in this museum-within-a-museum-from prehistory to classical to the Hellenistic-Roman periods. When completed sometime after 2005, the overall exhibition space will total an enormous 60,000 square feet.

Upon entering the galleries from the Museum's Great Hall, the first object one encounters is an understated yet lovely bronze rod tripod stand from the early 6th century BC. The tripod would have supported a bronze vessel, and is adorned with couchant sphinxes and horse protomes that seem to presage the Parthenon steeds, with their heads and forelegs emerging from beneath a base. The tripod's legs form lyrical intersections between verticals and horizontals, and it is also pleasing and surprising to look through the object into the sculpture hall across a vista that culminates in the stout Sardis Column. To follow the chronology of the galleries, the visitor begins in the Pre-History Gallery. Here one finds enigmatic Cycladic figures and the magnificent seated harp player that is the earliest of the small number of known representations of musicians. The Minoan Gems collection, displayed on the west wall, is comprised of a 1926 bequest of seals from the collection assembled by Richard B. Seager, an archeologist active in Crete. The diminutive seals, used for identification of ownership, resemble precious jewels and were carved from such materials as ivory, bone, shell, and soft stones, and later from harder stones such as rock crystal and hematite and semiprecious stones such as agate. Presented for the viewer are the actual stone, the impression it makes on clay, and a crisp photograph of that impression, allowing for three different ways to experience the image. The exquisitely-carved objects reward close investigation: an octopus, surprisingly realistic with its delicate splaying tentacles, contrasts with an earlier, more abstract and stylized depiction of the same creature. From here, one may venture east into the Seventh and Sixth Century Gallery, (these two galleries are the Robert and Renée Belfer Court, Phase I of the greater renovation project), where one is offered a taste of the presentation style that carries through most of the new galleries: each vitrine is devoted to a different aspect of Greek life. Clever mixtures of materials (e.g. bronze, glass, terracotta) and artifacts (e.g. statuettes, drinking cups, plates) create crosscurrents and interrelationships within and among displays that not only highlight different aspects of Greek life but also make the works come alive, offering the viewer an extremely accessible "transversal cut through the civilization," according to Philippe de Montebello. For example, a display of bronze helmets and belly guards creates a dialogue with a nearby vitrine, which contains three terracotta perfume vases in the form of helmeted heads. The warriors' eyes steadfastly peek out from between the bronze flaps-one can envision therefore the usage of the actual bronze helmets. Exhibit clusters throughout the galleries are devoted to religion, myth, death and the afterlife, the gods, heroes, and the symposium. In the Jaharis Gallery is a fascinating group of objects related to sports and the Panathenaic festivals: large prize amphorae for sacred olive oil (some decorated with images of footraces), bronze statuettes of athletes, a marble discos, and even various items associated with post-exercise cleansing such as a strigil, used by athletes for wiping the skin clean after cleansing with oil.

The new galleries are organized such that a chronological tour necessitates crossing back and forth through the central spine, the magnificent McKim, Mead and White hallway modeled on the Braccio Nuovo of the Vatican Museum (which itself was modeled on the public baths of ancient Rome). Following this path, the large statues correspond with the centuries celebrated in the galleries on either side. Probably one of the more significant transformations brought about by the renovation is the alteration of previous traffic patterns. Previously, Museum visitors on their way to the cafeteria rushed through this hallway, then lined with Cypriot sculptures, blandly displayed and pushed up against the wall. Now named the Mary and Michael Jaharis Gallery, the sunlit room is ideal for exhibiting large scale marble sculpture. Traffic has slowed to a contemplative stroll, and visitors now linger, taking the time to view these works fully in the round and admire the changing effects of sunlight on the carved surfaces. One cannot miss the Statue of a Wounded Warrior, located practically in the center of the gallery. The unusual stance of the warrior-his feet are carefully placed on a sloping surface-has provoked various identifications, including the Greek hero Protesilaos, who ignored an oracle's warning that the first Greek to step on Trojan soil would be the first to die in battle.

|

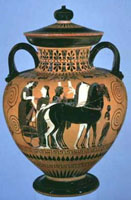

The Dietrich von Bothmer Galleries, named for a longtime curator in the Greek and Roman Department, display a vast array of sixth and fifth century BC red-figure and black-figure painted pots. The elegant presentations breathe fresh life into the vases, which were previously displayed unimaginatively, row upon row, in a dark room on the second floor of the Museum. Two works by Andokides, set in separate vitrines but in close proximity, skillfully illustrate the transition from black-figure to red-figure vase painting. Nearby, a terracotta column krater painted by Lydos is cleverly juxtaposed with a case containing pieced-together fragments of another krater decorated by the same artist. In the second von Bothmer Gallery, the lavishly decorated and dramatic Euphronios vase creates a striking dialogue with the more understated Berlin vase, which depicts against a stark background a singer playing a kithara, a lyre used for the recitation of epic poetry. With its delicate lines and emphatic silhouette, the Berlin vase is a masterpiece of Greek vase painting.

To aid the interpretation of the often enigmatic Greek pots, related materials are presented alongside to convey a much larger sense of culture. For example, in the Judy and Michael H. Steinhardt Gallery, a tiny bronze statuette of a horse shares a case with a terracotta neck-amphora decorated with a painted chariot drawn by four horses. Another vitrine focuses on a single artist, illustrating one of the many laborious tasks of archeologists: isolating a particular artistic hand from so many others. Here, a group of works by the Amasis painter illustrate the artist's wide range of subjects, which includes an imaginative rendering of Poseidon's underwater stables described in the Iliad, as well as vignettes of everyday life such as a woman working a loom.

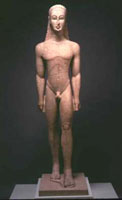

In order to comprehend the rationale behind the presentations, as well as to appreciate fully each artifact, multiple visits to these galleries are necessary. Particular objects not to be missed include a pelican's foot shell used for pouring a burial libation, located in the Weiner Gallery. Perhaps the most delicate object in the entire collection, the carved marble is so thin it is virtually translucent. Another startling discovery located nearby is the set of larger-than-life-size eyes from a lost bronze statue. Eerie yet stunning, the eyes are composed of bronze, marble, frit, quartz, and obsidian, and are carefully created with each iris and pupil ringed with eyelashes. Perhaps the most poignant object can be found among the Museums' monumental collection of stone funeral reliefs: a skillfully carved Parian marble grave stele that depicts a young girl clutching her pet doves, solemnly kissing one on the beak. The New York Kouros in the Michael Steinhardt gallery is one of the earliest marble statues of a human figure carved in Attica. Intended to mark the grave of a young Athenian aristocrat, the Kouros stands rigidly, in a pose derived from Egyptian art. A terracotta volute krater in the Stavros and Dana‘ Costopoulos Gallery is striking in its architectonic character. The staid vertical ribbing of the body contrasts with the lively and exquisitely detailed crowning frieze that depicts the frolicking Dionysos and his retinue.

One quibble with the presentation in the new galleries discussed by Gary Wills in The New York Review of Books (June 10, 1999) is the mere passing glance at the role of women, slavery, and homosexuality in Greek life. While war, sports, religion, and myth are fascinating and offer a wealth of interrelationships between objects, Wills thought that perhaps more could have been done to reflect these current and hotly debated topics. From exploring the galleries, however, it seems evident that the curators have seriously pondered the particular strengths of what is essentially a conservative collection. While the objects might include illustrations of such subjects as homosexuality or slaver, they do not necessarily lend themselves to in-depth qualitative or quantitative inquiries. The thematic groupings are didactic and extremely educational, yet they are not meant to be dramatically pioneering.

Overall, the new galleries reward many levels of inquiry. The casual visitor can wander through the galleries, investigating objects that catch the eye. The addition of four doors leading into the main hall enable a variety of itineraries, including one that adheres to a strict chronology. Abundant explanatory wall texts, maps, and object labels provide a wealth of information. The objects themselves, through their groupings and juxtapositions, provoke contemplation, and encourage the visitor to form opinions and draw further conclusions. The didactic presentation stimulates the casual viewer, provides further information for those with a stronger background in the field, and offers novel and fresh ways of approaching the material for scholars and specialists. A deeply satisfying experience on any level.

Postscript: In April, 2000, The Metropolitan Museum of Art opened the new Cypriot galleries, which display major works from the Cesnola Collection, formed by Luigi Palma di Cesnola (1832-1904), who became American consul on Cyprus in 1865. After excavating there for over a decade, in 1872 he sold his collection to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and seven years later became the Museum's first director. Issues of cultural patrimony aside, it is the most significant collection of ancient Cypriot art outside of Cyprus. The four new galleries trace the chronological development of Cypriot art through a selection of works from the Cesnola Collection, which covers a time span from about 2500 BC until about 300 AD.

© 2000 Part and Dana Pilson. All Rights Reserved.