Spartan

Desires: Eugenics and the Sculptural Program of the 1915 Panama-Pacific

International Exposition

by Brian Edward Hack

No theme is as ubiquitous to the histories of art and nature as the struggle against the New. Aberrations from the acceptable generally emerge to an onslaught of criticism and contempt from those doomed souls tangled in the quagmire of traditional practice; for these casualties of artistic revolution, the retreat into the darkened depths of history is a slow and bitter one. Critics of the Post-Impressionists and their Modernist progeny were particularly cantankerous during their descent, desperately holding fast to conventional modes of representation. For many American artists, such as F.W. Ruckstull and Lorado Taft, Modernism was a sure sign of human artistic and psychological decay, an apocalypse first presaged by the arrival of the Aesthetic Movement.1 The art of the Gilded Age, replete with marble and mural reminders of civic responsibility, was in many ways a response to the hedonistic, Epicurean philosophy of the Aesthetic Movement as first propagated by Oscar Wilde during his lecture tour across America in 1882.

Conservative American critics, vehemently stolid in the stagnant grandeur of classical historicism, bemoaned the apparent downward spiral into decadence well into the twentieth century. They interpreted the Modernist fragmentation of space and the defilement of the human form as the products of a degenerate, feeble-minded temperament; such radical, imported notions of modernity, they argued, were as detrimental to the nation's mental and physical purity as the influx of (and miscegenation with) immigrant populations. As F.W. Ruckstull proclaimed in 1917, "If we hope to preserve our democracy and help it along towards a higher perfection and prevent ourselves from sliding backwards towards slavery, we must above all be loyal to the laws and truths of nature."2 It is no coincidence that the rise of Modernism coincided with both the rises in popularity of eugenics-the misapplication of Charles Darwin's principle of natural selection to human cultures-and of an art that expressed its tenets of biological and psychological perfection.

Developed in 1883 by Charles Darwin's cousin, Francis Galton (1822 -1911), eugenics merged the science of heredity with the somewhat misguided interpretation of Darwinian evolution as "survival of the fittest" (a phrase coined by Herbert Spencer, not Darwin). Eugenic proposals included extensive genealogical background checks before marriage in order to increase the likelihood of having perfect children (positive eugenics) and the sterilization or elimination of those deemed unfit for human procreation (negative eugenics).3 The 'Science' of eugenics soon permeated American biology and hygiene textbooks, marriage manuals, and silent films such as The Black Stork (1916)4 which advocated euthanasia for unfit newborns. Among its many adamant adherents were John D. Rockefeller, George Eastman, Alexander Graham Bell, J.H. Kellogg, Margaret Sanger, Theodore Roosevelt, and university presidents such as Charles W. Eliot (Harvard) and David Starr Jordan (Stanford). With its moral and patriotic imperative to create the finest and fittest nation possible, eugenics seemed tailor-made for the American notion of a progressive society fulfilling the promise of manifest destiny.

A number of influential societies were established in America to promote eugenic ideals: The Race Betterment Foundation, led by J.H. Kellogg; The American Breeders Association, an organization devoted to successful animal husbandry that turned its attention to human livestock in 1906; The Galton Society; and The American Eugenics Society. In addition, the Carnegie-funded Station for Experimental Evolution (1904) and the Eugenics Record Office (1910) were created at Cold Spring Harbor, New York, directed by famed eugenicist Charles B. Davenport. Several International Congresses of Eugenics were held, with devastating ultimate results: laws permitting the sterilization for criminals and the developmentally disadvantaged, often performed without their consent, were put into effect in several states. Such measures were supported by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, who famously maintained "It is better for all the world if instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime, or let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind."5 Families proving themselves genetically pure would vie for glory and medals in "Fittest Family" contests in county fairs across the nation.

The expression of eugenics in sculpture, if addressed at all, has been generally relegated to the idealized depictions (largely despised/ignored by art historians) of Aryan nationalism during the Third Reich.6 American figurative sculpture, equally infused with idealized forms embodying human perfection, is typically perceived as classical or as Beaux-Arts-inspired rather than as emblematic of current biological thought. Representational sculpture in the age of Modernism was, however, not merely a carryover from the century past, but an active response-albeit one of desperation-to what was perceived as the degradation of form. Its advocates-convinced that the cubist and futurist butchers were mentally and morally degenerate-worked in silent collusion with the promoters of eugenics.

|

The Panama-Pacific International Exposition, held in San Francisco in 1915, served as one of the clearest national expressions of eugenic philosophy.7 Promoted as a celebration of the completion of the Panama Canal, the exposition showcased the decade of human progress since the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis. Among the advancements noted by one exposition reporter were the wireless, the aeroplane, the automobile, and "selective breeding".8 The Second Race Betterment Congress was held in conjunction with the fair (the first was held at Battle Creek, Michigan, home of the famed sanitarium directed by J.H. Kellogg); so popular was the Congress that "Race Betterment Week" was declared at the exposition. An extremely popular eugenics exhibit in the exposition's Palace of Education further advanced the cause.9 Illustrated with printed depictions of sculptures depicting motherhood and classical physique, the banner for the "Race Betterment" exhibit enticed exposition goers to enter and view the myriad of heredity charts lurking amidst plaster copies of Apollos, Venuses, and Atlases.10

It is in the fair's actual sculptural program, however, that the themes of human advancement, physical and mental perfection, scientific family planning, and heredity were emphasized for public awareness and adherence. Two of America's foremost sculptors, Karl Bitter and Alexander Stirling Calder, served as Chief and Acting Chief, respectively, of Sculpture for the exposition; Bitter directed the completion of models by New York sculptors on the East Coast, while Calder supervised their enlargement in staff (a mixture of fiber and plaster) in San Francisco.11 Tragically, Bitter was struck and killed by an automobile in April of 1915-two months after the exposition opened-and never was able to witness the full expression of his vision.

Thematically centered around "the Spirit and Romance of Man's Development, Energy, Adventure, Aspirations and Achievements", the exposition intended to explore "[Man's] relation to the Cosmos, to Nature, and to the Divine."12 The very plan of the exposition, featuring large open courtyards entitled The Court of the Universe (McKim, Mead and White), The Court of Ages(Louis Christian Mullgardt), and The Court of the Four Seasons (Henry Bacon), suggested a harmony with natural forces. Under Bitter and Calder's direction, philosophical unity was achieved between the sculptural and architectural programs, with the final result being an amalgamation of eugenics and evolutionary theory.

|

Calder's own Fountain of Energy, dubbed "The Coming of the Superman" by poet Edwin Markham,13 greeted visitors as they entered the front gates of the exposition. Representing the exertion of human labor put towards the completion of the Panama Canal, its symbolic meaning was described as "the approach of the Super-Energy of the Future." Two winged heralds-Fame and Valor, depicted as male and female to suggest man's duality-announce the arrival of this equestrian übermensch.14 Like Adolf A. Weinman's Rising Sun in the Court of the Universe, this new figure of masculinity-physically and mentally at one with Nature-reflects the eugenic ideal, the New Man who has answered The Call of the Twentieth Century, David Starr Jordan's plea for the youth of the nation to become fit in order to perpetuate a stronger, genetically-rich race. "Already the fad of the drooping spirit, the end-of-the-century pose, has given way to the rush of the strenuous life, to the feeling that struggle brings its own reward," observed Jordan. "The weak, the incompetent, the untrained, the dissipated find no growing welcome in the century which is coming."15

The Court of Abundance, originally called the Court of Ages, centered on the theme of evolution through natural selection. Louis Christian Mullgardt's Tower of Ages, adorned with Chester Beach's Altar of Human Evolution, illustrated the progress of humankind from the primordial muck to the Middle Ages and upward to the age of mortal divinity. Finial sculptures of Primitive Man and Primitive Woman by Albert Weinert traversed the top of the tower, which Mullgardt had ornamented with sculpted tadpoles, crawfish, and other forms of aquatic and floral life.

|

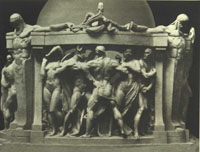

In the center of the court stood Robert I. Aitken's Fountain of the Earth, a gargantuan globe surrounded by four narrative panels that explored the evolution of human love. Separating the panels were four massive hermes representing milestones of the ages. The Southern-most panel depicted the consequences of 'physical parenthood without enlightenment'16; marriage books such as The Eugenic Family (1914) warned of such lustful dangers, pleading for restraint in the face of breeding with degenerates. In the second panel [facing West] Man has attained intellect, rejecting these baser instincts. The Northern panel, "Survival of the Fittest," features three male figures of various constitutions-"the protester, the conqueror, and the weakly resigned"-surrounded by one morally strong and one morally weak woman. Both sexes battle the forces of moral sloth to live up to the responsibility they hold for future generations. In the final panel, 'The Lesson of Love', the strongest, most intellectual male and female achieve a perfect, carefully orchestrated union based upon a reverence for genetics and sexual selection.

A California sculptor, Aitken was a member of novelist Jack London's circle. An apostle of Herbert Spencer and the spiritual Monism of Ernst Haeckel, London had once attended a university extension course on evolution taught by David Starr Jordan,17 and promoted eugenic ideas in novels such as Martin Eden. Health-conscious, sun-worshipping California became a hotbed of eugenics discussion, due in part to the works of Jordan and London. The state also led the nation in enforced sterilizations; some ten thousand criminals and mentally challenged individuals were sterilized in California between 1909 and 1945.18 Fountain of the Earth, with its ever-churning globe whirled along by the hands of Time and Destiny, represents the eugenic hope for a biological utopia.

|

Perfect offspring of "goodly heritage"-as revealed by the medallion given to 'Fittest Families' by the American Eugenics Society-was the primary goal of the eugenic movement and, accordingly, depictions of mothers and children proliferated during the period.19 The Panama-Pacific exposition featured numerous examples, most notably Charles Grafly's Pioneer Mother. Representing the strong-willed American spirit, Grafly's matriarch sternly offers her naturally eugenic offspring-nude in their Nordic splendor-to the future. During this period, researchers at the Eugenics Records Office were scouring the country in search of genealogical accounts of American families, in hopes of rooting out the degenerate genetic strands; Pioneer Mother stands as a testament to a culture consumed with genetic pedigree. "In eugenics," remarked W. Grant Hague, "the women of the race have the instrument wherewith to save the world·the supreme civilizing instrument of the future."20 As it was believed that a mother's thoughts during pregnancy influenced the physical and mental health (or lack thereof) of her baby, eugenicists often cited the importance of women in creating a pure, eugenic race.21 Depictions of happy, healthy babies were plentiful at the exposition; among the many sculptural examples of innocent, playful nude children included Edith Woodman Burroughs' Fountain of Youth; Edward Berge's Wildflower; Bela Lyon Pratt's Boy with a Fish; Janet Scudder's Young Diana, Young Pan, and Fountain of the Fighting Boys; and Edith Barretto Parsons' The Duck Baby.22

The interest in Nordic children, fitness, health, and sun-worship, while certainly characteristic of the eugenics movement, also posits these works in alliance with symbolist artists such as P.S. Krøyer and Léon Fréderic, as well as with Scandinavian authors such as Knut Hansun and Henrik Ibsen (although like the work of Edvard Munch, Ibsen's genetically-cursed characters seem arguments for eugenics rather than displays of its glorious results). The theme of biological inheritance loomed large in the art and literature of the Nordic countries, all of which practiced enforced sterilization-a fact which, unsurprisingly, American eugenicists applauded. While immigrants from Eastern Europe were believed to be the cause of racial degeneracy in this country (the theme of Madison Grant's The Passing of the Great Race), new arrivals from Norway and Germany received a welcome as hearty as their homogeneous stock.23

|

The Forecourt of the Four Seasons, dominated by Evelyn Beatrice Longman's Fountain of Ceres adapted the goddess of Agriculture to the familiar role and stance of Nike. Offering her "crown of summer to the world"24, Ceres brandishes a scepter fashioned from a corn stalk. While congruous with the Court's seasonal theme, the fountain coincides with the changing breakfast fare for American families. In the ten years prior to the exposition, cereal-largely due to Corn Flakes, the invention of eugenicist J.H. Kellogg and his brother W.K.-replaced meat and other cooked foods as the morning meal.25 As the goddess of abundance and the namesake of cereal, Ceres reflects the reinvigoration of humankind through proper digestion.26 Similarly, the science of Sanitary Chemistry (Home Economics) arose during this period, championed by the euthenics ('science of controlled environment') of Ellen Henrietta Richards, who believed that cleanliness and the healthful preparation of food would improve the fitness of human stock (it is also at this period that the Boy Scouts of America is founded, an organization which also promoted health and moral behavior as a means to achieving a better society).

While Modernism was well represented within the Palace of Fine Arts, the sculptors who decorated the Panama-Pacific International Exposition appealed to contemporary sensibilities through their subtle incorporation of evolutionary and eugenic principles; Calder and Bitter's program seemed a Counter-Reformation in miniature, a rebellion against the apparent thoughtlessness of the Modern with an onslaught of contemporary progressive philosophy. Eugenics served as the conservative answer to immigration, philanthropy, poverty, and Modernism; all social ills-including Modern Art-could be eradicated genetically. Although eugenics lost its credibility with most scientists during the 1920s, the pseudo-science retained public interest until the Second World War, when the horrifying consequences of national eugenics became brutally apparent.

The triumph of Abstraction, a victory which seems so inevitable and righteous in hindsight, has watered down the vitriol which deluged its historical moment; decades before Entartete Kunst, respected American thinkers were labeling Modern Art "the expression of mental dyspepsia and physical impotence."27 A reassessment of the concept of Modernism in terms of the eugenic response of American artists and critics, one which keeps in mind the fact that James Earle Fraser, Sherry Fry, Edith Woodman Burroughs, Chester Beach, and Robert I. Aitken shared space with the Post-Impressionists and Cubists in the 1913 Armory Show (as well as in the galleries of the Panama-Pacific Exposition), is long overdue. To imply that the Modern was a universal experience by limiting its definition to Abstraction is to sterilize-if not eliminate-untold layers of historical truth.

Additional images for this article are available at:http://kbccartsmart.tripod.com/panamapacific/index.html

References:

1. See F.W. Ruckstull, Great Works of Art and What Makes Them Great (Garden City: Garden City Publishing Company, 1925); Lorado Taft, Modern Tendencies in Sculpture (Freeport: Books for Libraries Press, 1970 [1921]). Both Ruckstull and Taft viewed Auguste Rodin as the primary force behind the degeneration of Art; while Ruckstull believed the French sculptor to be mentally deranged, and provided an appendix written by a physician to prove it, Taft's text features a doctored illustration of Rodin's Man with the Broken Nose that appears as if the sculpture is leeringly ogling a bust (also by Rodin) of a Young Girl (Figures 1, 2). Elsewhere Taft laments that Matisse's "primitive" figures "do love and propagate", citing works by Brancusi and Archipenko as their degenerate offspring (27).

2. Ruckstull, 369.

3. For a more thorough examination of eugenics, see: Steven Selden, Inheriting Shame: The Story of Eugenics and Racism in America (New York: Teachers College Press, 1999); Carl N. Degler, In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991); Robert J. Richards; Darwin and the Emergence of Evolutionary Theories of Mind and Behavior (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987); and Richard Hofstadter, Social Darwinism in American Thought (Boston: The Beacon Press, 1965 [1944]). Primary sources on eugenics are considerable, ranging from medical and marriage counseling texts to more philosophical studies. See: W. Grant Hague, The Eugenic Marriage: A Personal Guide to the New Science of Better Living and Better Babies in Four Volumes (New York: The Review of Reviews Company, 1914); T.W. Shannon, Nature's Secrets Revealed: Scientific Knowledge of the Laws of Sex Life and Heredity, or Eugenics (Marietta (OH): S.A. Mullikin Company, 1916); Robert L. Leslie, Ed., The Science of Eugenics and Sex Life, Love, Marriage, Maternity: The Regeneration of the Human Race (New York: Martin & Murray Company, 1917); Madison Grant, The Passing of the Great Race, or The Racial Basis of European History (New York: Charles Scribners & Sons, 1916); William J. Robinson, Birth Control, or The Limitation of Offspring by Prevenception (New York: Eugenics Publishing Company, 1929 [1916]); and David Starr Jordan, The Heredity of Richard Roe: A Discussion of the Principles of Eugenics (Boston: The Beacon Press, 1911).

4. Martin S. Pernick, The Black Stork: Eugenics and the Death of "Defective" Babies in American Medicine and Motion Pictures Since 1915 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996).

5. Degler, 47.

6. One notable exception to the taboo on discussing sculpture done for the National Socialist cause is Peter Adam's copiously illustrated Art of the Third Reich (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992).

7. For a discussion of the role of eugenics in the Panama-Pacific and other expositions, see: Robert W. Rydell, World of Fairs: The Century-of-Progress Expositions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993); and Robert W. Rydell, John E. Findling, and Kimberly D. Pelle, Fair America: World's Fairs in the United States (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 2000).

8. French Strother, "The Panama-Pacific International Exposition", Scribners [?], detached article, 1915. Collection of the author.

9. Rydell, World of Fairs, 40-42.

10. Frank Morton Todd, The Story of the Exposition [Vol. IV] (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1921), 38.

11. Frank Morton Todd, The Story of the Exposition [Vo. I ] (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1921), 354.

12. Stella G.S. Perry, The Sculpture and Murals of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition (San Francisco: The Walgreen Company, 1915), 1.

13. ibid, 3-4.

14. Stella G.S. Perry, The Sculpture and Mural Decorations of the Exposition: A Pictorial Survey of the Art of the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, with an Introduction by A. Stirling Calder (San Francisco: Paul Elder and Company, 1915).

15. David Starr Jordan, The Call of the Twentieth Century: An Address to Young Men (Cambridge: University Press, 1903), pp. 4, 11.

16. Perry, The Sculpture and Mural Decorations of the Exposition, 72-78.

17. David Starr Jordan, The Days of a Man [Vol. 2] (Yonkers-on-Hudson: World Book Company, 1922), 460. See also: King Hendricks and Irving Shepard, Eds., The Letters of Jack London (New York: The Odyssey Press, 1965). Although London disagreed with Jordan's idea that war was eugenically evil as left the country bereft of its best breeding stock, he maintained that "He [Jordan] is, to a certain extent, a hero of mine. He is so clean, and broad, and wholesome"(p. 47).

18. Jonathan Gottshall is currently doing thesis research on this subject. His article based on these findings, "The Cutting Edge: Sterilization and Eugenics in California, 1909-1945", can be read online at http://www.gottshall.com/thesis/article.htm.

19. The Eugenic Family (1914), a four-volume guide to the production of better babies, used Lorado Taft's Mother and Child as the frontispiece for the third volume; The Story of Eugenics cited Raphael's Madonna of the Chair as the finest work of art ever created, one which pregnant women should contemplate if they wish their children to be culturally-enriched by the time they left the womb.

20. Hague, 53.

21. See: David Starr Jordan, The Heredity of Richard Roe, 71. "[The mother's] part in heredity is not less than that of the father. Her part in the higher heredity, the character each man works out for himself, is even greater. In spite of the facts of race-suicide, and the numbers of foolish wives and broken families, motherhood was never so highly esteemed in civilized races as it is today. Never were women so well fitted for their obligations for duties which do not cease with child-bearing, but continue through the noble degrees of child-rearing and lifelong sympathy and friendship."

22. For a discussion of the sculptures of children at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, see: Edith Kinney Stellmann, The Exposition Babies: An Idyl of the Fine Arts Colonnade (San Francisco: H.S. Crocker Company, 1915).

23. Jordan, The Heredity of Richard Roe, 120. "Love of our country is just as genuine in Norwegian or German dialects as it is in English or Irish."

24. Perry, The Sculpture and Mural Decorations of the Exposition, 100.

25. Strother, 356.

26. For a lively and thorough discussion of cereal and its smooth passage through the body, see: J.H. Kellogg, The Itinerary Of A Breakfast: A Popular Account of the Travels of a Breakfast through the Food Tube and of the Ten Gates and Several Stations through Which It Passes, also of the Obstacles Which It Sometimes Meets (New York: Funk & Wagnalls, 1920).

27. Jordan, The Heredity of Richard Roe, 140.

© 2000 Part and Brian Edward Hack. All Rights Reserved.