|

Special Feature: Latin America: The Last Avant-Garde |

|

Number 12: (In)efficacy |

|

The Making and Re-Making of the American Myth in Dorothea

Lange’s Plantation Overseer Photographs |

|

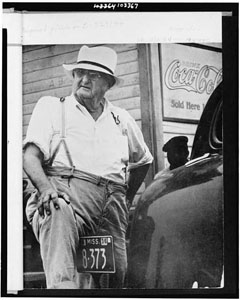

| In June of 1936, Dorothea Lange took photographs of an unnamed man identified as a Mississippi plantation owner standing prominently in front of several of his farm laborers (Figures 1, 2). The white owner’s foot is confidently perched upon the rear bumper of a car as he engages in a conversation with another man barely inside the photographer’s frame. Four black workers sit behind the owner on the steps of a store which sells, among other things, Coca-Cola. The lanky workmen are idle, awaiting instructions from their boss, a stout fellow who appears to be about sixty-five years old. The domination of the frame by the white landowner coupled with the submissive position of the black workers (not to mention the boss/worker relationship suggested by the photograph’s title) point to racial and class differences, providing a hint that the legacy of the slavery system dismantled seven decades earlier was still very much alive in 1936 in Mississippi.

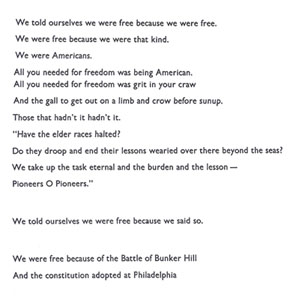

Lange’s images were powerful and radical statements about the persistence of racial inequality, which she, along with fellow F.S.A. photographer Marion Post Wolcott, insisted upon integrating into her work for the New Deal organization. But in Lange’s case, few people ever got to see the images as she intended them to be seen.[1] After Lange composed, developed, selected and submitted her uncropped photographs to her boss Roy Stryker at the Farm Security Administration in Washington D.C. – about a thousand miles away from Clarksdale – the images were altered to fit the New Deal organization’s mission, which was “to rouse outrage, sadness or any other emotional state aimed at changing conditions” while making “the ‘forgotten’ people visible.”[2] Yet in the course of making these “forgotten” rural Americans hit hard by the Great Depression visible, the black plantation workers became invisible. A generously cropped version of Lange’s original photograph was offered free of charge to publications nationwide in order to rouse support among the East Coast urban upper-classes for Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal relief programs by revealing the plight of the rural poor.[3] (Figure 3) After all, the F.S.A.’s task was not to reveal America’s flaws and racial inequalities, but to make convincing, photography-based, moral, humanist appeals to be targeted at people from upper classes to promote the spirit of charity – and of course, Roosevelt’s reform agenda.[4] In doing this, according to Martha Rosler, the F.S.A. actually functioned to reassure viewers of the photographs of their own elevated social positions as the non-suffering “givers” of charity, while avoiding overtly challenging the inequities of American society.[5] (In 1936, it would be doubtful that white, affluent East Coasters would be interested in helping the idle black men who sit on the porch.[6] Typically, the F.S.A. favored generalized, iconic images which roused sympathy but assigned no blame to either the proud victims of the misfortune or to their oppressors).[7]

Therefore, in spite of the F.S.A.’s reformist aspirations as the promotional branch of a New Deal program, its use of photography promoted F.D.R.’s social policies while confirming and legitimating a selectively liberal and humanist conservatism, and leaving the basic myths of American democracy – such as equality and equal opportunity for all citizens – unchallenged. (However tempting it might be to condemn the F.S.A. for soft-selling selective reform and using its power to promote a politicized message, we must remember that this was precisely the organization’s job). Through a discussion of several versions of Dorothea Lange’s Plantation Overseer. Mississippi Delta, Near Clarksdale, Mississippi (1936), which were edited to remove hints of Lange’s suggestion of social inequities such as racism in America, I hope to illustrate the degree to which Lange’s insistence upon raising the issues of racism were seen as too “radical,” and were suppressed in favor of towing the New Deal line to create the illusion of national solidarity while masking issues of social division. I also wish to suggest that the F.S.A.’s policy of allowing unsupervised reproduction and manipulation of its photography by the media also permitted uncontrolled reinterpretations and recontextualizations which often changed the meaning of the original images substantially. This policy enabled the images to take on meanings which further obviated Lange’s original intent to document racial inequality. A closer look at several versions of Lange’s photographs before and after their publication will reveal the photographs’ politicized repackaging by the F.S.A. and other media.[8] In Lange’s photograph Plantation Overseer. Mississippi Delta, Near Clarksdale, Mississippi (Figure 1), which was introduced briefly at the start of this paper, the plantation owner in the foreground cocks his head slightly to his left, with his mouth slightly open. He appears to have been candidly caught in mid-conversation with the person in the left edge of the photograph. He seems a friendly man, the kind who talks to strangers. The expression in the landowner’s eyes is obscured by his squint, the glint of sun glare in the lenses of his glasses and the shadow under the rim of his hat. He has weathered the sun and elements, as his facial expression and wrinkled face and neck attest, with a self-assured, proud, calm, down-to-earth dignity. His sleeves are rolled up for the act of work. The plantation owner’s plumpness and his very presence at the rural store (which advertises Coca-Cola, one of the most recognizable and enduring of America’s mass-produced products) and the presence of the automobile – a luxury good – suggest that the plantation owner plays his part in the American economy, and that this role has been rewarded accordingly. This man in the foreground therefore becomes a one-man embodiment of the “American Dream”: that hard work and fortitude will bring good fortune to all. The commonly reproduced, altered version of Lange’s photograph focuses only on the plantation owner (Figure 3), leaving us to ponder the “American Dream” in the light of such alterations, which imply that sometimes even good fortune can be rattled by greater economic forces which are larger than even the most earnest American. In spite of the fact that a man as proud and earnest as this plantation owner -who holds his head high and survived the previous economic depression in the late nineteenth century - would likely never ask for help, that is precisely why he needs it. This man is the salt of the earth, and he deserves our help simply because sometimes tough times befall good people, and people have to look out for each other.[9] True to form, rather than examine the causes of the human hardship or delve into the reasons why the “American Dream” might have failed during the Great Depression, the alterations made to this F.S.A. photograph shifts the image’s meaning instead to humanitarianism, illustrating “what happened when we turned our backs on fellow citizens and allowed them to be ravaged,” and simultaneously appealing to affluent Americans to support Roosevelt’s efforts to help the less fortunate.[10] In Roosevelt’s own words, “social change was difficult if not impossible ‘in our civilization unless you have sentiment.’”[11] F.S.A. photography such as Lange’s rouses this sentiment through appealing to the moral goodness of affluent urban viewers to help their fellow man. The photographs did so by capturing “not only what a place or a thing or a person looks like, but it must also tell the audience what it would feel like to be an actual witness to the scene.”[12] Lange became a stand-in for the viewer, a surrogate who allowed the viewer of published images to feel like he or she was participating in the moment. Yet by showing the viewers a vision of a social class and region of the country that was very different from their own, the images also kept the viewer from truly stepping into the other person’s shoes – and this in fact affirmed the subject’s position as the much less fortunate “other,” or as the subject of the “gaze.”[13] Ever mindful of the audience of the photographs, Lange and other F.S.A. photographers worked to convey the message that the possible recipients of federal relief programs were not lazy, but that they were decent, hard-working people who were victims of something they alone were powerless to change, the Great Depression. Affluent urbanite viewers of the photograph in its popular published form (Figure 3), after all, were well aware that President Roosevelt had a year earlier, at their insistence, finally eliminated a New Deal program which gave open-ended cash payments to the unemployed.[14] (In the words of Roosevelt, “To dole out relief in this way was is to administer a narcotic, a subtle destroyer of the human spirit. …Work must be found for able-bodied, but destitute workers”).[15] By creating and distributing an image of only the plantation owner – proud, able-bodied and down-to-earth, Lange’s photograph was altered to fit the explicit mission of the Farm Security Administration perfectly. We see a man with spirit who seeks no pity, works hard and deserves our help. But curiously, given the opportunity to frame and capture this very image (Figure 3) herself, Lange chose not to move closer to the plantation owner and focus solely on him. Instead she made the conscious choice to frame the portly white man in front of the black plantation workers, who sit and stand idly behind him. (Figure 1) The workers are thin and diminutive in comparison to the presence of the landowner, who dominates the image.[16] When the viewer looks past the plantation owner to consider the men on the porch, suddenly visions of fortitude and the “American Dream”’s availability to all hard-working people are destabilized. Lange prompts us to face the fact that in 1936 in Mississippi, the notion of equality and the promise of unbridled opportunity to all citizens did not apply to all people of all races – no matter what the Declaration of Independence or Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms” speech might have promised.[17] Lange’s photograph is intentionally provocative, and it unveils inequalities and presents problems inherent in the myth of America as a land of equal opportunity. But the very capturing of this image in a time and a place where lynchings were still commonplace – and were executed by white upper classes (if we recall, viewers of published F.S.A. photographs were also white and were from the upper classes) – was a risky political endeavor.[18] Because Lange’s images were so racially charged, and because they critiqued America’s social problems at a time when the country’s economic infrastructure was in shambles and the New Deal was needed to reassure affluent white voters of their elevated status, the F.S.A. created a generously-cropped version of the original image which is devoid of any reference to the plantation workers (except for the tiny distant head of a black man who peeps over the front of the car, just below the Coca-Cola sign). (Figure 3) This image seems to have been altered in the darkroom to darken both the Cola-Cola sign and the black man’s face until the ode to capitalism sang loudly and the black man’s face tellingly fell into obscurity in the background. Thus, the image’s political content was reframed to meet the mission of the F.S.A. and to promote Roosevelt’s politics while downplaying or rather, eliminating, Lange’s own political view. But another important level of reinterpretation and recontextualization of Lange’s photographs occurred after they left the hands of Roy Stryker and the F.S.A. and were adapted to meet the varying needs of individual publications. By virtue of the F.S.A.’s policy of allowing publishers unrestricted, unsupervised reproduction of the images, Lange’s “Plantation Overseer. Mississippi Delta, Near Clarksdale, Mississippi” was among thousands of images which were reinterpreted by editors or art directors at various media outlets by re-cropping the photographs, by positioning them next to other images, or by adding text.[19] These subtle decisions altered possible interpretations and guided readers to view the photographs in differing contexts at the unfettered discretion of individual publications. The F.S.A. asserted no claim or control over the use of the images.[20] For example, when the poet Archibald MacLeish aspired to write a book-length poem in response to images from the F.S.A.’s archives, he selected the cropped version of Lange’s image (Figure 3) as one of 88 photographs to illustrate his short book Land of the Free (1938).[21] (Figure 4) The photograph that appears in MacLeish’s book is even more tightly cropped than the F.S.A. version.[22] (Figure 3) The plantation owner’s hat is skimmed by the edge of the frame, providing a point of tension at the top of the photograph and suggesting that the exact cropping of the image was subject to production and printing constraints. In this case, however, the most radical reinterpretation of the image is not the way it was cropped, but its complete recontextualization by nearby literature. MacLeish’s poem (Figure 5) shares an open-page spread with Lange’s image. The entire poem spans the length of the book and its basic plot unfolds as follows: (1) Because “we” owned our land and were self-sufficient, “we Americans” were free. (2) Now those days are over, and dust storms, droughts and the Great Depression have forced “us” to leave our land, “we” wonder if our freedom is gone, too. (3) “We” wonder whether rugged individualism – the very spirit that raped and conquered America – has passed. MacLeish suggests that “we” must band together to survive and must fight against the social and natural forces that oppress us. “We” can no longer be free without each other.[23] Thus, MacLeish proposes in 1938 that the notion of human solidarity is necessary in our industrial-minded, interdependent society.

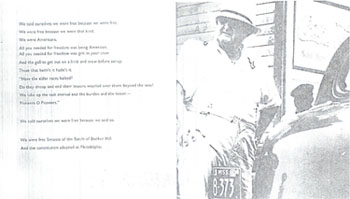

A version of Lange’s image without the black laborers present is adjacent to the part of the poem in which “we” connect our freedom to our land-ownership (Figure 4). (This is step one of the poem’s plot. On the next two pages we see a dramatic turn as Lange’s Migrant Mother appears next to the words “Now we don’t know.”)[24] Within the imposed literary context, we see Lange’s plantation owner as he thinks about his freedom. He tells himself he is free because he is just “that kind,” because he knows that freedom is just “a grit in your craw.” Our plantation owner’s freedom and apparent grit were bestowed upon him by the Battle of Bunker Hill and the Constitution. Freedom is his birthright. It is his presumption. He owns land, therefore he is free. (Therefore, it seems logical that the black farm workers be excluded from this image because they do not own land, and following MacLeish’s logic, they must not be free. Thus, MacLeish re-contextualizes Lange’s photograph of racial oppression and changes it into a sympathetic portrait of a rural American ruminating about freedom). But MacLeish’s poem then takes command of the plot of this man’s life and implies that the plantation owner is two pages away from losing everything he owns. Yet no information provided by Lange supports the implication that this man lost his land in the Great Depression or in the onset of mass farming.[25] In addition to adapting photography such as Lange’s to suit the needs of the poem, MacLeish gives real humans an unreal voice. This may (and likely, does) present an inaccurate distortion of the photograph’s subjects’ life stories. According to John Rogers Puckett, the possibility of allowing the subjects of the photographs to speak for themselves is tempting:

But this position raises interesting questions about suppositions of authenticity. Curiously, no readers object to the inherently subjective nature of MacLeish’s writing. Yet when the poems are coupled with photographs – which are assumed to somehow be more “objective” than words – concerns about the possible exploitation of the photographs’ subjects abound.[27] MacLeish’s assumption of the task of giving these photographs a new narrative story may have been because their status as recognizable icons or symbols invites reinterpretation in the absence of hints of literary specificity.[28] According to Martha Rosler, images which become “symbolic” are “debased” and have “content-free content.”[29] (Although it seems more likely that the images contain an entirely new and just as politicized content). In other words, because these pictures cannot tell us their stories in their own words, we are eager to assume the task and to become their voices. But in this process, the stories inevitably become politically motivated. Allan Sekula suggests that the relationship of photographs to their discourse (whether that discourse is determined by the context in which each of Lange’s images are used, or the context of the discourse she might have intended when she shot the photographs) is always inherently tied to specific interests, and the resulting photographs speak with a “voice of anonymous authority and preclude the possibility of anything but affirmation.”[30] Every image has an argument and is endowed with a motivated – and thereby politicized – message. The many versions of Lange’s Plantation Overseer. Mississippi Delta, Near Clarksdale, Mississippi are certainly no exception. Despite the F.S.A.’s reformist aspirations, it was an organization which had a mission to promote the Roosevelt administration’s social policies through humanist appeals to an upper-class audience – while doing little to challenge the problematic assumptions of the American myth (such as equality for all citizens). A study of several versions of Lange’s Plantation Overseer photograph reveals that political motivations were manifest at every stage of the image-making process – from Lange’s composition and selection of the photographs, to Stryker’s editing, cropping and distribution of them in order to promote the goals of the F.S.A., to the individual publications’ recontextualization of the photograph to convey another specific but often different message. Each time the photographs were used, they were endowed with a new set of political meanings and interpretive possibilities. But given their role as publicity devices for Roosevelt’s reform program, this seems only appropriate.

Kris Belden-Adams is working on her doctoral dissertation on photography's complicated relationship to time at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York.

Endnotes [1] One notable exception is a book published about 40 years later, which featured the image as an illustration of sharecropping. (Figure 6) See F. Jack Hurley, Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography in the Thirties (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972), 19. However, Lange’s original lengthy caption does not identify the farm workers as sharecroppers. It is very possible that the men were temporary workers or “wage hands” instead, according to Melvyn Dubofsky and Stephen Burwood, The Great Depression and the New Deal: Women and Minorities During the Great Depression (New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1990), 170-217. The potential misidentification of the men in Lange’s image as “sharecroppers” was a result of the picture’s proximity to re-contextualizing verbiage. (Incidentally, in contemporary journalistic practice, leading a reader to make misidentifications due to intentional or unintentional text/photo association is regarded as a form of libel against the subjects of the image.) These misleading uses of F.S.A. photography were very common, and they resulted from the organization’s policy of giving up the control of the use of their photographs by outside publications. Stryker himself admits this in a 1973 essay; see Roy Emerson Stryker, “The F.S.A. Collection of Photographs,” Photography in Print (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981), 351.

[2] Lili Corbus Bezner, Photography and Politics

in America: From the New Deal into the Cold War (Baltimore

and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999), 9.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, “‘Four Freedoms’

Message to Congress,” Political and Social Thought in

America: 1870-1970 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970),

105.

For Further Reading: Amenta, Edwin. Bold Relief: Institutional Politics and the Origins of Modern American Social Policy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998. 80-161. Bezner, Lili Corbus. Photography and Politics in America: From the New Deal into the Cold War. Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1999. 1-15. Daniel, Pete, Foresta, Merry A., Stange, Maren and Stein, Sally, eds. Official Images: New Deal Photography. Washington, D.C.: The Smithsonian Institution Press, 1987. Dubofsky, Melvyn and Burwood, Stephen. Women and Minorities During the Great Depression. New York and London: Garland Publishing, Inc., 1990. Farm Security Administration, Digital Archives. “American Memory.” [on-line electronic archives] Accessed September 29, 2004. Available from http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/index.html. Hurley, F. Jack. Portrait of a Decade: Roy Stryker and the Development of Documentary Photography in the Thirties. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University, 1972. Ions, Edmund, ed. “Four Freedoms, From Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s Message to Congress.” Political and Social Thought in America, 1870-1970. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1970. 103-106. MacLeish, Archibald. Land of the Free. New York: Da Capo Press, Inc., 1977. Museum of Modern Art, The. The Bitter Years, 1935-1941: Rural America as Seen By the Photographers of the Farm Security Administration. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1962. Puckett, John Rogers. Five Photo-Textual Documents from the Great Depression. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1984. Reissman, Leonard. Inequality in American Society: Social Stratification. Glenview, Ill.: Scott, Foresman and Co., 1973. Rosler, Martha. “In, Around, and Afterthoughts (On Documentary Photography),” The Contest of Meaning: Critical Histories of Photography. Boston: MIT Press, 1989. 172-196. Sekula, Allan. “On the Invention of Photographic Meaning,” Photography in Print. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. 452-473. Stange, Maren. Symbols of Ideal Life: 1890-1950. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989. 89-131. Stryker, Roy Emerson. “The F.S.A. Collection of Photographs,” Photography in Print. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1981. 349-354. Tagg, John. “The Currency of the Photograph: New Deal Reformism and Documentary Rhetoric,” The Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1988. 153-183. |