| In this paper

we shall examine the role played by artist Alberto da Veiga Guignard

(Nova Friburgo, RJ 1896 – Belo Horizonte, MG, 1962) in the

development of modern art in Brazil. A painter, drawer and teacher

belonging to the second generation of modern artists active in Brazil

from the 1930s on, Guignard is recognized today as one of the most

original and important Brazilian artists of the 20th century. His

quite irregular oeuvre reached its high point in the early 1940s,

with his first “Imaginary Landscapes” and “Saint

John Nights”, themes he would continue to work on throughout

his life. Along with some portraits, these landscapes allow for

a perception of Guignard’s singular contribution to the formation

of a distinctly Brazilian visuality in modern art.

Although often mistakenly taken for a naïve or primitive artist,

Guignard underwent solid academic training in Europe, particularly

in Germany. His father died when he was a child, and in 1907 his

family moved to Switzerland. Before his final return to Brazil in

1929, already in his adulthood, Guignard had studied in Switzerland,

France and Germany, where he enrolled in the Royal Academy of Fine

Arts of Munich in 1917. His studies at the academy provided him

with training in drawing and painting, with rigorous discipline.

Yet, even the artist himself seemed rather unclear about this period,

he referred vaguely to an exhibition of the Die Brücke group

that he had seen in Munich and which had deeply impressed him. He

did however confess that it was at the Munich Art Collection, more

than in school, that he had learned his art, observing and copying

the works there by Flemish and Dutch artists.

Although Guignard participated in exhibitions since 1922, his European

production remains lost, which makes it difficult for us to know

how his artwork evolved during his years there. The only thing we

know about this period is based on the artist’s own recollection

that refers to the time he spent in Florence from 1925 to 1928 which

represented his “path to freedom.” According to Argentine

painter Emílio Pettoruti, a friend of Guignard’s since

the 1920s, in Florence he assiduously studied the work of Botticelli,

which together with his studies of Japanese printmaking gave him

a sense for the decorative.

During these years he took part in exhibitions which included the

Biennale di Venezia as well as the Salon d’Automne and Salon

des Indépendants in Paris. He met Picasso and Utrillo at

the Café Duomo and became interested mainly in the painting

of Dufy, Matisse and Rousseau. Although it is not possible to analyze

Guignard’s painting from this period, we can certainly find

echoes of his European experience and his direct contact with modern

art in the work he developed following his return to Brazil.

As he related twenty years later, upon his arrival in Rio de Janeiro

he suffered two shocks: the first was the conservative spirit of

the city’s art world at that time; the second, even more profound,

was Brazil’s particular nature, colors and landscape. From

this point on, until the end of his life, his technique underwent

a slow but steady and complete revision.

Before focusing on an analysis of some of his artworks, it is worth

remembering the situation of modern art in Brazil in the late ’20s

and early ’30s. Roughly speaking, the late-coming development

of Brazilian modern art took place in two phases. The first was

centered on the provincial city of São Paulo in the late

1910s, and is characterized by an attitude of rupture with the preceding

art. This small group included Anita Malfatti, Di Cavalcanti, Oswald

de Andrade, Tarsila do Amaral and Victor Brecheret and sought –

as one of its main theoreticians, writer and art critic Mário

de Andrade, pointed out – to renovate the cultural environment

and the national intelligence, which at the beginning of the 1920s

required a “warlike and eminently destructive” attitude.

At this moment, the challenge was to combine the desire for formal

updating, by way of the European avant-garde, with the aim to rediscover

Brazil in terms of its popular traditions and heterogeneous culture

suffocated by the 19th-century Brazilian intelligentsia’s

“colonized and conservative veneration of things French.”

At his 1942 conference on the modernist movement, Mário de

Andrade summarized this double aim according to three fundamental

principles: “the permanent right to aesthetic research; the

updating of Brazilian artistic intelligence; and the establishment

of a national creative consciousness.” Initially, this group

did not espouse a single approach for Brazilian art, and in terms

of the visual arts it accommodated the formal lessons of cubism,

the spirit of expressionism and the colorful fauvism without major

conflicts.

A second generation of modern artists, or a second modernist phase,

took place from 1930 onward, when Brazilian modern art became more

socially engaged, showing more concern for depicting Brazil’s

social reality while focusing less on formal issues. Naturally,

this movement closely followed a recession of European avant-garde

experimentation and the expansion of Mexican muralism throughout

the Americas. The artist who best represents this interwar period

is Candido Portinari, Brazil’s official modernist painter

in the 1940s.

Although a fuller discussion of the subject lies outside the scope

of this article, it should be pointed out that, with few exceptions,

the modernist movement in Brazil was indissociable from nationalist

aims. At an early stage, the modernist nationalism took the form,

for example, of Oswald de Andrade’s anthropophagic primitivism

in 1928. For him, the mere updating of the medium was not enough;

it was necessary to “swallow” what came from outside

and to re-create it based on local experience. As early as 1920,

Mário de Andrade was suspicious of the praise that Tarsila

do Amaral, then living in Paris, heaped on cubism. For him, modern

art as it was being developed in the hegemonic center ran the risk

of becoming “excessively aestheticizing” and, in a good-humored

tone, he invited Tarsila to return to Brazil to found a new movement,

“Matavirgismo” [Virginforestism].

In fact, there are various versions of Nationalism. There exists

a series of gradations lying between the one end of the spectrum

– the position of these first modernists, who sought to give

rise to the “new man” by rejecting the classical European

values while re-valorizing the Brazilian primitive art with African

and indigenous roots (and which art critic Mário Pedrosa

called, kindly, “primordial, irreducible and anti-erudite”

“primitive, naïve Nationalism”) ; on the other,

the superficial and strict forms of patriotic Nationalism serving

conservative and reactionary aims, especially from the mid-1930s

onward.

During the era instated by President Getúlio Vargas and

called the Estado Novo – the moment at which modern art finally

became publicly accepted and to a certain extent institutionalized

in Brazil – Portinari’s socially motivated ideological

Nationalism provided the acceptable model of modern art. In a classical-realist

form, but with expressive and salient deformations (of the feet

and hands, for example), this art was nevertheless constrained within

an acceptable decorum, and embodied the nationalist question and

that of the Brazilian man in the figure of the worker. For art critic

Ronaldo Brito, Portinari represented the triumph of the “literary

character of the ideology of Brazilianness.”

In short, for better or for worse, the nationalist question was

a constant in the Brazilian modernism of the first half of the 20th

century. While the research into “Brazilianness” enriched

the Brazilian visuality, raising awareness in regard to popular

manifestations and the image of the common folk which up to then

had hovered at the fringe of the cultural system, on the other hand,

at certain moments, it acted as a censor when it was taken as a

doctrine to be followed and as an antidote to the more radical experiments.

This ambiguity – the commitment to national awareness and

the autonomy of visual-arts research – marks a good part of

the most consistent production of Brazilian modern art.

Although it was not an outgrowth of these developments, certainly

Guignard’s Brazilian production was influenced by these issues.

What makes it so singular, however, is the fact that its primitive

appearance rarely resorts to the ease of anecdote nor recurs to

solutions based on extra-artistic commitment. As art historian Sônia

Salzstein has observed, “his specificity does not derive from

‘Brazilian thematics,’ but from the original way that

this thematics is infused within the essential power of his oeuvre.

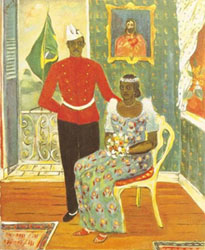

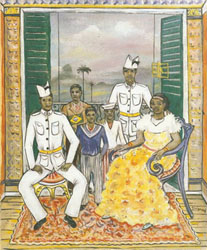

After a production with surrealist leanings in the late 1920s,

Guignard began a series of paintings in which he sought to capture

simple scenes or people from Brazilian life, in family portraits

and interior scenes such as Os Noivos [The Fiancés],

1937 [Figure 1], or Família do Fuzileiro Naval [The Marine’s

Family], no date [Figure 2]. This production, which at the

time was called “Lyric Nationalism” evinced Guignard’s

preference for the more prosaic and less heroic aspects of national

life. Both paintings feature people from a less-favored social class,

whom Guignard nevertheless valorizes through colorist treatment

and Matisse-influenced composition.

|

Figure 1. Os noivos [The fiancés], 1937

Oil on canveas, 58 x 48 cm

Collection Museus Castro Maya, Rio de Janeiro |

| |

|

|

Figure 2. Família do fuzileiro naval [Marine’s

family], no date.

Oil on wood, 58 x 48 cm

Collection Mário de Andrade - IEB-USP, São Paulo |

In these paintings, the modern palate of contrasting colors is

blended with decorative elements typical of popular culture. However,

here these decorative elements – the flowers, the fabrics

printed in popular patterns, the drawings on the wallpaper, the

stripes on the boys’ clothes, the arabesques of the railing

on the balcony – do not function as elements for structuring

space. It seems that the conspicuous presence and energy of the

decorative in the composition does not contaminate the human figures

beyond the surface of their clothes. The latent happiness of the

environment seems to contrast with the stern attitude of the people,

who show no hint of a smile.

There is a further, even more significant contrast. When we observe

the landscape projected like a backdrop to the portrait of the Marine’s

family, we perceive that there is a significant difference between

the lines used inside the room and the colored patches making up

the outside scene. Certainly, there is a transition between the

interior and exterior colors, yet the landscape’s scarcely

delineated character, its atmospheric expansion, contrasts with

the relative rigidity of the architecture and the people.

This same paradoxical construction can be observed in a 1939 landscape,

in which Guignard deals with the theme of the “Saint John’s

Festival” traditionally held in Brazil in the month of June.

Festa de São João [Saint John’s Festival],

1939 [Figure 3], offers an aerial view, from a distance, of the

nocturnal celebrations of Saint John’s Day in a typical Brazilian

town. This is one of the most traditional festivals in popular culture,

celebrated during the month of June, when colorful balloons rise

into the night sky to celebrate the days of Saint John, Saint Anthony

and Saint Peter. Here there is a striking contrast between the architecture

of the colonial town in the foreground and the image of the mountains

and sky that takes up nearly two-thirds of the canvas.

|

Figure 3. Festa de São João

[St. John´s Festival], 1939

Oil on canvas, 55 x 80 cm

Collection Ricardo Akagawa, São Paulo |

Guignard’s June festival landscapes were gradually taken

over by this indefinite space that seems like a dilution, were it

not for a paper balloon, a train or a church, or even a small image

of the painter himself, which seem like attempts to delineate this

nature in a process of change, though in no wise imposing a structure

on it. Indeed, as we can see in Paisagem de Minas [Minas Gerais

Landscape] (Figure 4), there is even a suggestion of movement

in the cloud-mountains that appear in counterpoint to the static

quality of the figures.

|

Figure 4. Paisagem de Minas Gerais [Minas

Gerais Landscape], 1950

Oil on wood, 110 x 180 cm

Collection Angela Gutierrez, Belo Horizonte |

Obviously, this lack of integration between the well-delimited,

floating characters and the space constructed through overlain patches

of color cannot be attributed to a lack of technical skill on the

part of the artist, which would approximate him to the so-called

naïve artists. The spatial treatment used in this landscape

blends techniques drawn from an entire erudite pictorial tradition

stretching from Leonardo da Vinci to the German romantics, and also

including impressionist landscape, with which Guignard dialogues

here.

In the countless landscapes the artist painted throughout his life,

the paint gradually became more diluted. As it can be observed in

this Noite de São João [Saint John’s Night]

from 1961 (Figure 5), made one year before his death, the artist

worked on the modernist problem of the relation between figure and

background by means of a all-over space.

|

Figure 5. Noite de São João

[St. John’s Night], 1961

Oil on wood, 50 x 46 cm

Collection Roberto Marinho, Rio de Janeiro

|

The autonomy of the pictorial material revealed in this canvas

was a late-coming achievement, but an important one for Brazilian

art. It indicates a freer cultural environment, in which the artist

does not need to illustrate something in order to legitimize his

existence. As I see it, this autonomy was at this moment a very

helpful development for the conservative Brazilian art world, and

in a certain way it contributed to the formation of a later generation

of artists involved in important local movements (it should be noted

that Guignard was the professor and friend, for example, of two

neoconcrete artists, Amilcar de Castro and Franz Weissmann).

Returning our attention to the painting Noite de São

João, we note that the small figures that serve to orient

us in this indefinite and blurred space – and which are a

direct reference to Brazilian culture – almost seem to be

floating, as though they were not actually rooted in the landscape.

Made by quick brushstrokes that evoke only their outlines, the fragility

of these little churches, little balloons and little trains somehow

evinces Guignard’s melancholic view of this pre-industrial

country, moving along at a slow pace. While there is certainly no

condemnation of this situation, the nostalgia that seems to permeate

this painting conveys an identity that perhaps pertains finally

to the realm of imagination or memory, and which the painting sought

to make real. Far from the overoptimistic patriotism and social

realism prevailing in the culture and art in Brazil at that time,

Guignard focused on this inward and mysterious country, and, solely

through the visual arts, apprehended its irreducible experience.

Endnotes

[1] Andrade, Mário. “O Movimento Modernista”

(Conference held at the Casa do Estudante do Brasil no Rio de Janeiro

em 1942). In: Mestres do Modernismo. Milliet, Maria Alice

(ed.). São Paulo: Imprensa Oficial, Fundação

José e Paulina Nemirovsky and Pinacoteca do Estado de São

Paulo, 2005, p. 238.

[2] Ibid., p. 244.

[3] Pedrosa, Mário. “Semana de Arte Moderna.”

In: Acadêmicos e modernos. Arantes, Otília

(ed.). São Paulo: Edusp, 1998, pp. 144–145.

[4] Brito, Ronaldo. “O trauma do moderno.” In: Experiência

crítica. Lima, Sueli de (org.). São Paulo: Cosac

Naify, 2005.

[5] Salzstein, Sônia. “Um ponto de vista singular.”

In: Guignard: uma seleção da obra do artista

(exhibition catalog). Texts by Sônia Salzstein, Rodrigo Naves,

Iberê Camargo, Amílcar de Castro, and others. São

Paulo: CCSP, Museu Lasar Segall, 1992, p. 19.

Bibliography

Alberto da Veiga Guignard, 1896-1962. Rio de Janeiro: Edições

Pinakotheke, 2005. Catálogo de Exposição. Max

Perlingeiro (Apresentação). Pinakotheke (Organização).

Brito, Ronaldo. “O trauma do moderno.” In: Experiência

crítica. Lima, Sueli de (org.). São Paulo: Cosac

Naify, 2005.

Boghici, Jean (Org.). O humanismo lírico de Guignard.

Apresentação Frederico Morais; coordenação

Noemia Buarque de Hollanda. Rio de Janeiro: MNBA, 2000.

Frota, Lélia Coelho. Guignard: arte, vida. Rio

de Janeiro: Campos Gerais, 1997.

Guignard. Uma seleção da obra do artista.

Curadoria Sônia Salzstein; textos de Rodrigo Naves, Sônia

Salzstein, Iberè Camargo e Amílcar de Castro. São

Paulo: Centro Cultural São Paulo, 1992.

Milliet, Maria Alice (org.). Mestres do Modernismo. São

Paulo: Pinacoteca do Estado, 2005.

Morais, Frederico. Alberto da Veiga Guignard. Rio de Janeiro:

Monteiro Soares, 1979.

Naves, Rodrigo. A forma difícil: ensaios sobre arte

brasileira. São Paulo: Ática, 1996.

Pedrosa, Mário. “A paisagem de Guignard”. In:

Textos escolhidos III – Acadêmicos e Modernos.

Arantes, Otília (org.). São Paulo: Edusp, 2004.

Vieira, Ivone Luzia. A Escola Guignard na cultura modernista

de Minas: 1944-1962. Pedro Leopoldo: CESA, 1988.

Zilio, Carlos (Coord.) A modernidade em Guignard. Textos

de Carlos Zílio, Ronaldo Brito et all. Rio de Janeiro: PUC/Empresas

Petróleo Ipiranga, s.d.

|