|

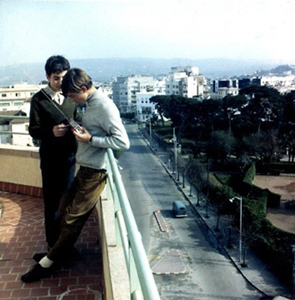

Olivier Debroise with friend, Tanger, 1966

A few years ago, upon a short reconnaissance trip to Mexico City,

I recall going with my long time friend Alberto to the Ghandi bookstore

off the Quevedo metro station in the Coyoacan district. I had then

taken the salutary decision to move my fieldwork site from my native

Morocco to search and probe family resemblances at work in another,

so-called alternative modernity. Alberto, well aware of my anxiety

over dominant geopolitical determinations, my inability to welcome

contemporary peripheral nationalisms as viable counter-narratives

of modernity, and mixed-feelings towards the aesthetics and erotics,

the libidinal economies, of cross-cultural encounters mediated through

peripheral national cultures, was determined—not without a

sense of affectionate pride and complicity— to update me coute

que coute via overwhelming reading suggestions. At that stage of

our disciplinary training, still able to maintain a distance from

the well-oiled machine of academic anthropology in the United States,

a book was simply a curio-site, a prosthetic affective landscape,

and a weapon to deflect and temper nativist and culturalist claims

one inexorably encounters during fieldwork. I had some money from

a small travel grant, so I indulged gluttonously. Among the books

I would come across were Olivier Debroise’s.

One may dwell on and resist the distinction between the ‘ordinary’

and the ‘exceptional’ but this would be a vain exercise

to frame the singular and ungovernable life (alas, painfully too

short) of Olivier Debroise: art historian, filmmaker, writer, curator,

fellow traveler and foreign body in peripheral cultures of nationalism,

and friend who took anthropology’s modernist concept of going

native to an extreme form during the three intellectually prolific

and intense decades he spent in Mexico, blurring through his innovative

curatorial practice the very distinctions of strange and the familiar,

native and foreigner, home and faraway places. Olivier belonged

to that exceptional lineage of cosmopolitan modernists and avant-gardists—artists,

filmmakers, writers and intellectuals whose work he would nonetheless

passionately disarticulate—who have crisscrossed the political,

affective and aesthetic landscapes of peripheral modernities: Einsenstein

in Mexico, Jean Genet in Morocco, Duchamp in Buenos Aires, Maya

Deren in Haiti, Miguel Covarrubias in Bali to name only the most

prominent ones and the ones with whom he would no doubt feel elective

affinities with.

Why exceptional, and not ordinary? Because these eventful geographic

displacements troubled and intoxicated both sides of the travel,

and indeed Olivier’s multi-polar geopolitical and affective

crossings do not lend themselves to easy categorization. Not only

do they enact a singular blurring of North-South, South-North, North-North,

South-South characteristic of the sentimental and aesthetic peripatetic

journeys of cosmopolitan modernists and avant-gardists escaping

to faraway places to seek something more than mere exotic re-enchantment,

Olivier’s crossings (geographically and through his curatorial

vision, art historical research and writings as an experimental

novelist and filmmaker), can be seen as a patient and passionate

weaving of a connective tissue across peripheral modernities and

the construction of a curatorial dispositif understood as a counter-narrative

to both nationalist and neo-colonial forms of domination.

But Olivier’s three decade detour through Mexico (whether

that exceptional detour would become permanent is a question I would

always pose to him but would always be met with vague answers) exceeds

the economy of departure and arrival characteristic of the ethnographer’s

vocation of conducting short or long-term fieldwork (whether at

home or abroad) with the aim of ultimately carving a reflective

space upon removal from one’s site of research. Olivier’s

intervention privileged permanent becoming over the geopolitical

and academic privilege afforded by ethnographers who rely on reflexivity

after the fact: he was always in the midst of things, a unique non-academic

ethnographer not unlike the Mexican cosmopolitan modernist, visual

artist and amateur anthropologist Miguel Covarrubias he so admired.

And although not an ethnographer by training, Olivier can be considered

to have mined institutional and official anthropology of post-revolutionary

Mexico. As anthropologist Guillermo De la Pena remarks in his perceptive

essay ‘Nacionales y Extranjeros en la historia de la antropologia

Mexicana’:

There is a fundamental difference between foreign anthropologists

and Mexican anthropologists. Foreign anthropologists defined and

frame their work in purely academic terms, whereas their Mexican

colleagues tend to view anthropology in political terms, and not

only for ideological reasons.

A ‘Mexican’ ethnographer of sorts, Olivier was committed

to politicizing present-day traces of the constitutive assemblage

of Mexican post-revolutionary modernity: the link between Mexican

nationalist anthropology, the aesthetics of the historical vanguardia,

and the non-academic ethos of contemporary art. Olivier belonged

to that generation that saw in contemporary art practice the hope

to invent a non-academic form of critique, even if his own academic

research was conducted with a great deal of rigor, surgical precision

and innovation. Olivier managed to initiate liminal spaces between

academic and non-academic forms of interventions.

This gesture is particularly visible in his film Un Banquete in

Tetlapayac, a film I consider, from the standpoint of mining Mexican

nationalist anthropology’s fascination with a ‘deep

Mexico, Mexico profundo’, to be the most important film experiment

since Ruben Gamez’s irreverent piece ‘La Formula Secreta’

(1965). A Banquet in Tetlapayac (2000) ought perhaps to be approached

as nothing less and nothing more than a disarticulation of the connections

between avant-garde aesthetics, Mexican nationalism, and what art

historian Renato Gonzales-Mello has called “the role of Manuel

Gamio’s anthropology as a tool of social engineering.’

The film’s operates a jarring reversal of the naturalized

alliance between vanguardista aesthetics and the nationalist-ethnographic

imaginary of the 1920s and 30s in Mexico, a signature conceptual

gesture in Olivier’s work.

My friendship with Olivier coincided with the fact we both spent

our teenage years in Morocco (twenty years apart), where we attended

the same bourgeois Lycee Descartes, and shared a profound sense

of affinity in our engagement with Mexico: Olivier was committed

to it, I as an ethnographer passing through, intruding for a couple

of years only to return to the safety and ennui of academic life

in the United States. Olivier would remind me, time and again, of

the sense of familiarity he felt upon arrival to Mexico City in

the 1970s, and that, sensuously at least, he would feel at home

owing to the years he had spent in the cosmopolitan city of Tangiers.

It is with great regret he was unable to fulfill his wish of returning

to Tangiers next year where I had scheduled a screening of his film.

Tangiers: city of great foreigners and cosmopolitans, where Jean

Genet waited to die, Paul Bowles realized his sensuous haven, William

Burroughs sought his inter-zone, but in any event all had lived

or passed through Tangiers before or after also having spent time

in Mexico. Olivier spent a good ten years there, and sadly fell

short of returning to it. Mexico and Morocco, two national cultures

and messy peripheral modernities, enacted a strange repetition for

both Olivier and I. They both irritated and fascinated us. The space

in between these two modernities initiated a friendship between

us. In the end, I think it was, at least as far as our conversations

and friendships are concerned, neither about Mexico nor Morocco.

It was about the possibility of creating a future to come, political

and affective, through the precious gesture of linking secret geopolitical

affinities. This was the enigmatic gift of Olivier: exceptional

ethnographer and intractable foreigner meandering through a south-south

imaginary that has ceased to be an ideological horizon and has morphed

instead into a politicization of silent affinities across peripheral

modernities. It is this that makes of Olivier the exceptional intellectual

and friend I will dearly miss. |